Overview

Automated vehicles are challenging the status quo of transportation networks and the policies that support them. The technology is developing quickly and has the potential to make roadways safer, more efficient, and more accessible for Americans. However, commercial deployment is still several years away, and successful implementation is far from guaranteed.

To allow the technology to reach its full potential, governments at all levels need to adapt, especially on the state level. State governments have long played an important role in planning, regulating, and managing roadway networks, however AVs could entirely upend the existing federalist structure. This paper provides guidance on how states should prepare for an automated future by adapting their approach to motor vehicle regulations, infrastructure investment, and research.

Crafting sound policy approaches to AVs is not a straightforward process, as an AV does not have a singular definition. Instead, different “levels of automation” correspond to varying capabilities of the automated system and the role of the human driver. The policy framework directly correspond to the definitions of AVs, particularly in state-level responsibilities such as liability, licensing, and insurance. However, AVs are not commercially available yet and will not be widespread for many years. Planning for something that is not in widespread use, and designing policies to support it, is very difficult.

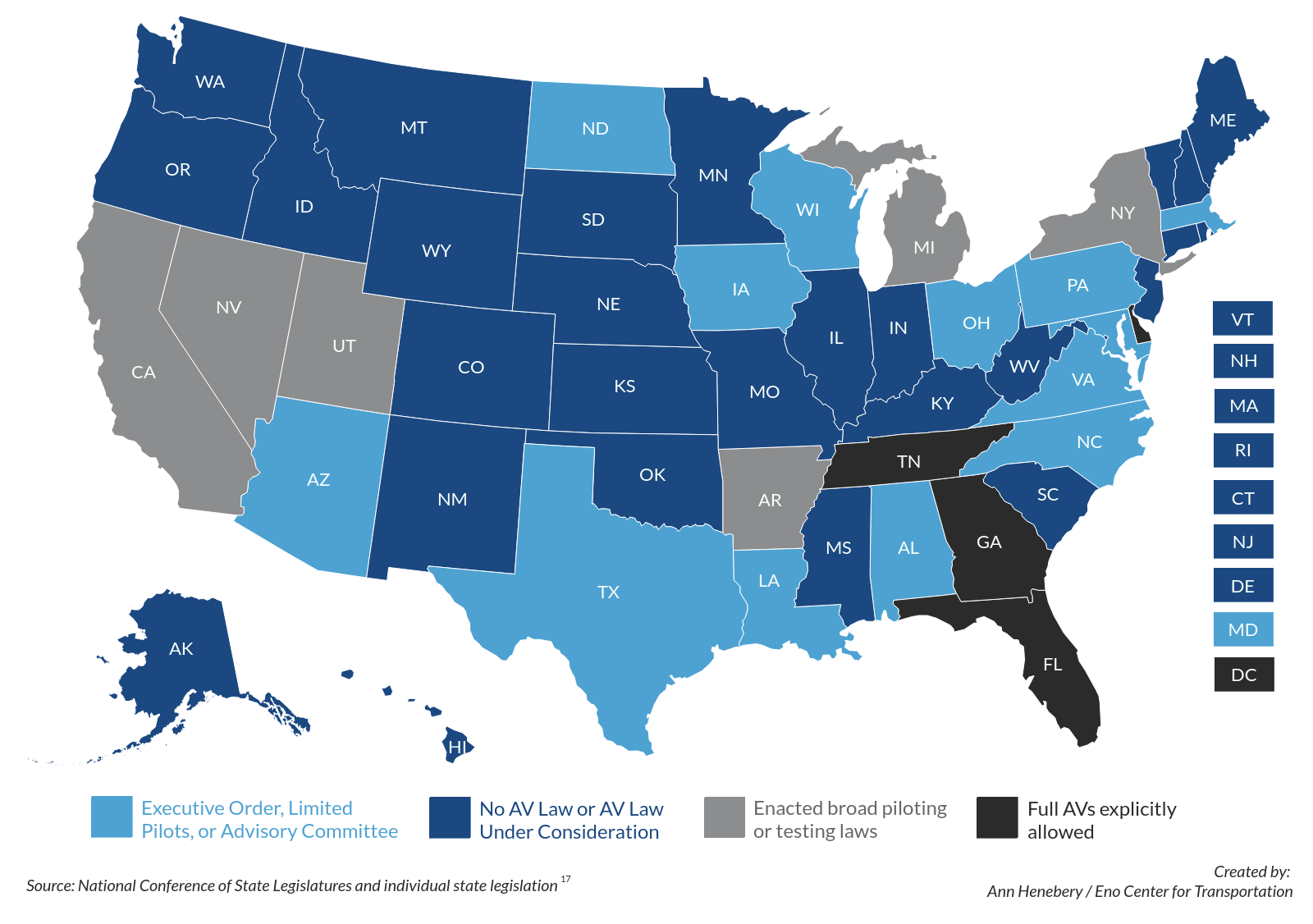

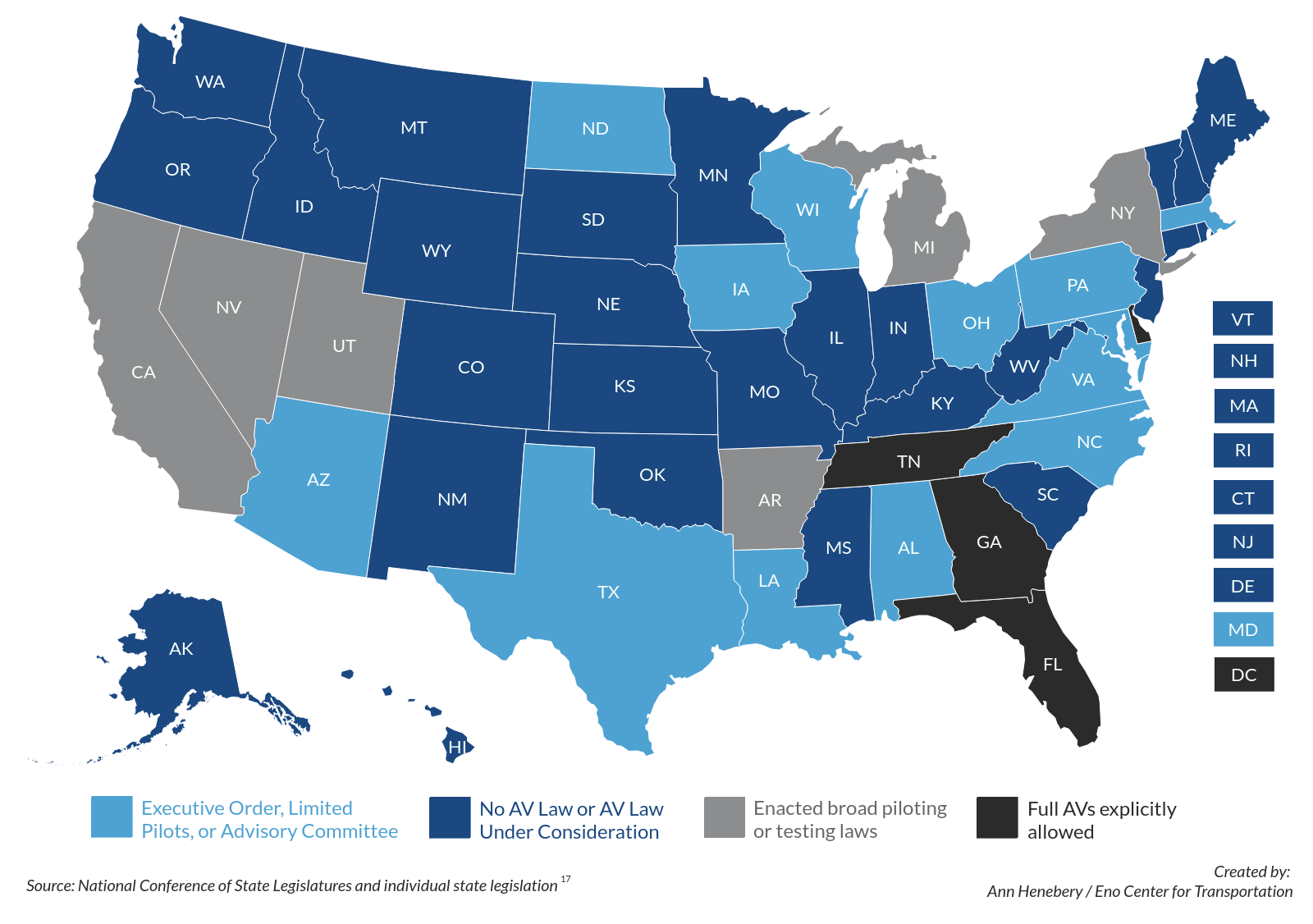

States have taken one of four approaches to AV policy. A few have fully legalized vehicles without drivers, some have passed laws that expressly permit testing, others have issued direct executive actions, and the rest are either developing laws or are waiting for the market to develop further. This report finds that, while any of these approaches can be effective in the short term, there are some general guidelines that states should follow to avoid regulatory pitfalls, prevent wasted public and private sector investments, and encourage the thoughtful implementation of AVs.

In terms of AV regulations, states need to be sure to adhere to consistent definitions. The “levels of automation”, as defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE), are the national standard and should be worked into all state AV policies. When developing these policies, states should understand legislation or regulatory action alone will not necessarily attract or deter AV testing. An entire ecosystem of engineers, manufacturing plants, and software developers along with good roadways and permissive rules is required to encourage AV testing.

When writing laws or executive orders, states need to be careful not to overdesign reporting requirements for manufacturers and tech firms as they continue to test and deploy AVs. While AV companies are not opposed to obtaining special operating permits or specific driver requirements, states must strike the right balance to avoid onerous bureaucracy or exposure of propriety corporate information. Fully self-driving vehicles are still years away from deployment, but in the meantime states should develop partnerships with AV companies, research groups, and localities in order to develop specific pilots to better understand the effects of AVs their roads.

States have long been responsible for regulating tort, liability, and insurance for roadway vehicles. AVs could prompt states to redefine some or all of those laws. To prepare, states need to work with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to harmonize tort and liability laws and enable consistent, national safety standards for commercial AV certification. Further, states need to review and update current traffic laws that may directly conflict with the operation of AVs on public roads.

To manage the entire regulatory process, states should form an AV advisory committee that monitors and advises on AV policy. Such an entity should include the variety of public and private sector stakeholders. In consultation with this group, states should create non-binding “statement of principles” for certain AV policies such as privacy, cybersecurity, roadway safety, consumer advocacy, and data sharing.

When it comes to infrastructure investment, the most beneficial action states can undertake is to improve roadway state-of-good-repair. Since automated vehicle technology works best on well-maintained and marked roads AV firms are naturally attracted to states with a commitment to fix-it-first. Advanced infrastructure investments, such as vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) technologies, could further enhance AV capabilities. However, connected vehicle technology (CV) is unproven and still in testing phases. Instead of committing significant funding to retrofitting their infrastructure, states should initiate tests of CV and V2I applications in order to better understand their potential benefits. In order to fund these improvements and other AV infrastructure needs, states should consider developing a road use fee for AVs. States can also experiment with using the fee to manage future demand and mitigate negative externalities.

States should be involved in AV research as it pertains to all possible effects of AVs on the broader transportation network. With the private sector leading the way on most AV development, state policymakers should establish themselves as facilitators, by encouraging pilot programs and research efforts at AV testing grounds. States can also fund research to understand how AVs could affect the broader transportation network and incorporate that into state transportation improvement plans.

Finally, states need to prepare for the future impacts of AVs on the workforce. With the potential disruptions AVs may have on employment, states should begin to examine and invest in programs that will help retrain workers who have lost jobs to automation. Partnering with universities and the private sector for targeted re-training or career development can enhance early efforts to mitigate job loss and prepare for future workforce challenges.

Sound and consistent policy at the state level will help automated vehicles to navigate safely and seamlessly no matter where they are operating. Policymakers should focus on this harmonization in order to allow AVs to reach their full potential while also maintaining the interests and safety of all road users.

The report provides action items based on three primary policy concerns for state governments:

-

Regulations

-

Infrastructure investment and funding

-

Research and workforce training

State Action Items:

1. AV Regulations at the State Level

- Legislation or regulatory action will not necessarily attract or deter AVs.

- Make sure testing AVs is not only allowed, but also that it fosters the development of an entire ecosystem of automakers and/or tech firms, research institutes, and localities engaged in the field. Also, states have an advantage when they collaborate with their neighbors. Although there is a competitive nature in state-level AV policy, each state will be more attractive to AV development if there are fewer regulatory hurdles at their borders.

- Adhere to consistent definitions

- Adopt the current (and future) NHTSA/SAE AV definitions, and use them when developing AV policies.

- Be careful not to overdesign reporting requirements for AV testing and deployment

- Design balanced reporting and permitting requirements that meet state needs for transparency and safety, but are not overly burdensome on AV testers. There is no rule of thumb on whether states should require AV testers to obtain a permit or submit reports to state officials. The AV industry is not opposed to testing permits and reporting, so long as the process is not too bureaucratic, cumbersome, or reveals proprietary corporate information.

- Work with NHTSA to harmonize current and future tort/liability and ensure consistent, national safety standards for commercial AV certification.

- Allow NHTSA to regulate the certification of commercially-ready AV technologies

- Continue to lead in states’ traditional regulatory areas such as licensing of human drivers, enforcing traffic laws, and regulating insurance and liability. States should assign crash liability to whatever (human or machine) is responsible for the driving task if there is an at-fault collision. AV developers should assume full liability in the case of a crash during testing. And AV firms should have insurance requirements for when their software is operating the vehicle.

- Work with NHTSA and neighboring states to ensure that the liability definitions have few discrepancies.

- Review and update current traffic laws

- Identify current state and local laws that might be in conflict with the capabilities of future commercial-ready AVs. Proactively modify those laws so that they allow for permitted or certified AV systems, while still requiring safe human operation.

- Authorize specific pilot programs

- Allow specific pilot programs for driverless AV testing through partnerships with AV developers, localities, and research groups.

- Form an AV advisory committee

- Create AV advisory committees of no more than 30 people that includes representatives from state government offices, local government, auto manufacturers, AV technology firms, safety advocates, public transit industry, trucking industry, taxi industry, and other relevant experts. States should rely on industry associations or rotating seats to ensure that group sizes are manageable yet include perspectives from different organizations in the industry.

- Create “statements of principles” for outstanding AV issues

- Develop nonbinding “statements of principles” that address the following topics:

- Privacy. States need to clearly delineate expectations about data ownership and access to the data in the case of a collision. Manufacturers must protect the privacy of the vehicle owners and companies should not be allowed to distribute personally identifiable information about vehicle owners or occupants without their approval and knowledge.

- Cybersecurity. States need to proactively define AV developers’ limited liability for crashes that result from a security breach, and ensure that all AV developers are taking cybersecurity seriously.

- Roadway safety. States should emphasize that AVs must be able to recognize, yield to, and share the roadway with all users of the roadway.

- Consumer advocacy. Consumers need to be aware of what their vehicle is capable of and what is it not. States can set principles for consumer information for new and used cars with AV features. In addition, consumers should be informed of data ownership rules prior to purchasing an AV.

- Data sharing. Creating initial guidelines for data sharing can set the stage for future data sharing agreements that can bring benefits to both public sector agencies and private companies.

2. State AV infrastructure investment and funding

- Invest in improving roadway state of good repair

- Use AVs as a way to galvanize support for a robust state of good repair program, targeted to unsafe roadways and work zones across the state.

- Pilot connected vehicle projects

- Initiate pilots of DSRC and 5G wireless CV technologies, particularly when a private entity is willing and able to support the pilot financially.

- Incorporate CV and AV technologies into state vehicle fleets as states turnover those vehicles and purchase new ones. Features like vehicle connectivity, automatic emergency braking, blind spot monitoring, and advanced cruise control can help to both prevent collisions and pilot new technologies.

- Consider developing a per-mile AV fee in concert with the federal government

- Research different approaches to implementing and using a VMT fee on AVs as a way to (1) create a new revenue stream for state transportation investment and (2) encourage the responsible use of AVs on public roadways.

3. State funded AV research and workforce training

- Foster the creation of testing grounds

- Establish AV testing grounds in partnership with universities, military bases, localities, industrial zones, and/or privately-managed roadways.

- Fund research to understand how AVs could affect the broader transportation network and incorporate findings into state transportation improvement plans

- Fund research at universities to understand the potential short-, medium-, and long-term effects of AVs on the transportation network, including the environment, social equity, and economic vitality.

- Revise state research procurement methods so that the results keep pace with the rapid development of AV technology. Procurement for research should target outcomes, rather than specific processes, for developing the research.

- Include AVs in long-range state transportation plans, not as a given outcome, but a potential scenario to anticipate.

- Invest in programs that develop the future workforce

- Form partnerships with universities and the private sector to implement targeted retraining or career development programs that proactively address and prepare for the adverse effects of automation.

- Work with academic institutions to retrain workers whose jobs may be lost to automation.

DOWNLOAD YOUR STATE AV CHECKLIST HERE.

Status of state policies related to automated driving, as of May 2017