June 22, 2018

Yesterday, the White House proposed an ambitious plan for reorganizing many agencies the federal government along functional lines, parts of which have been proposed in the past by Administrations of both parties and much of which makes a lot of sense.

But the proposal was largely lost in the media maelstrom of the week, and fundamental reorganization of the government has become next to impossible unless there is a clear political-media laser-like focus on a specific area of reform, which seems to be lacking here.

The White House Office of Management and Budget released an ambitious 130-page plan that proposed a great many reforms, including:

- Combining the existing Department of Labor and the Department of Education into a new Department of Education and Workforce, echoing longstanding Congressional committee jurisdictions.

- Splitting up the Army Corps of Engineers so that its port and navigable waterways functions would go to the Transportation Department and its water supply functions into the Department of the Interior.

- Take food stamps and other means-tested nutrition programs away from the Agriculture Department and put them with the rest of the means-tested welfare programs at the Health and Human Services Department, which would be renamed Department of Health and Public Welfare.

- Take rural housing assistance programs away from the Agriculture Department and combine them with the urban housing assistance programs at the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Move the Food and Drug Administration out of the Department of Health and Human Services and combine it with the Food Safety and Inspection Service under the Department of Agriculture.

- Abolish the salt water/fresh water distinction and merge the Commerce Department’s National Marine Fisheries Service (salt water) and the Interior Department’s Fish and Wildlife Service (fresh water) into one.

- Merge the the Department of the Interior’s Central Hazardous Materials Program and the Department of Agriculture’s Hazardous Materials Management program into the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program.

Where transportation is concerned, the biggest reform proposed by the Administration is the move of Corps of Engineers port/harbor, inland waterway, and coastal dredging functions to USDOT. Here is what the OMB document had to say:

Today, commercial navigation infrastructure—from deepening and widening navigation channels for commercial ships to terminals where ships dock and cranes that load and unload them—continues to make important contributions to many of America’s local and regional economies and is supported by investments from Federal, State, and local governments, port authorities, and the private sector. Yet, unlike other transportation sectors currently centralized under DOT, responsibilities for supporting the maritime industry’s ability to support the nation’s economy are split between the Corps, which supports navigation improvements and waterside port investments, and DOT, which supports landside port investments.

To fix this misalignment, the Administration proposes to consolidate the Corps’ commercial navigation mission into DOT. By consolidating these functions, the Administration would place a single Federal agency in charge of supporting maritime transportation investments. This consolidation will enable DOT to better align investments across maritime and other transportation sectors to ultimately create a more e cient transportation system. Similarly, the Administration proposes to move the Corps’ responsibilities for supporting investments in other water resources infrastructure such as ood control and aquatic ecosystem restoration to the Department of the Interior, which has responsibility for land and water resources management.

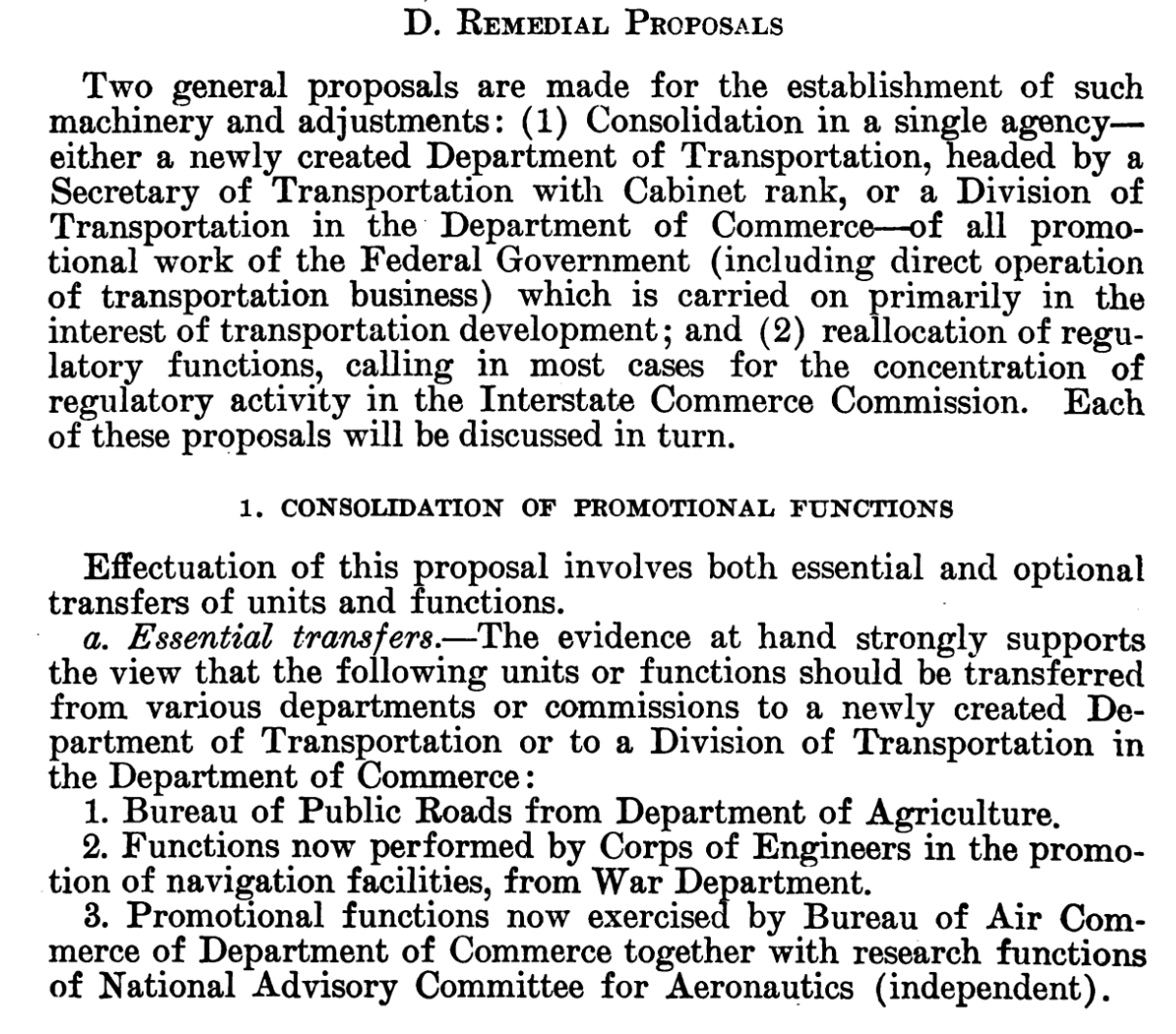

This idea is not out of the mainstream. Section 118 of the WRDA bill (H.R. 8) just passed by the House of Representatives asks for a National Academy of Sciences study about the merits of possible moving the Corps’ civil works staff out of the Defense Department to some other Department. In fact, the concept of splitting up the Corps and giving its navigation functions to a Department of Transportation goes back at least 81 years – check out this section of a 1937 Brookings Institution report to a Senate select committee examining government organization:

The White House plan also proposes a few other reforms that relate to the Department of Transportation:

- Getting DOT out of the business of operating modes of transportation and instead confine to the roles of regulating transportation and funding someone else’s transportation projects. This would be accomplished by spinning off responsibility for air traffic control to a non-governmental body, like Canada did to its air traffic control system, and privatizing the St. Lawrence Seaway. However, Congress has already implicitly but definitively rejected ATC spinoff for the time being, and there is no groundswell of desire to sell the Seaway, either.

- “transferring current U.S. Coast Guard responsibilities for permitting alterations to bridges and aids to coastal navigation to DOT would better align those functions with similar functions already carried out by DOT’s.”

- Transferring FEMA’s port security and rail/transit security grant programs to DOT.

- Directing the Office of the Secretary of Transportation to consider “whether OST’s organizational design is optimal for allowing it to most effectively carry out its statutory responsibilities” – particularly involving whether or not the Build America Bureau, which consolidated most DOT loan programs and discretionary grant programs in one place in the Secretary’s office, was really a good idea.

Almost all of the above would require action by Congress to change the law. And since legislation in Congress is controlled by committees of jurisdiction, such laws would require committees to voluntarily give up power over programs and agencies, which is against their self-interest. And, as we have all seen, it’s getting harder and harder for Congress to pass any kinds of laws these days. So general government-wide reorganization, or even limited excerpts of the above, would be a steep uphill battle.

It wasn’t always this way. Starting in 1939, Congress gave Presidents the power to move programs between departments and bureaus and consolidate agencies on their own, subject to a “legislative veto” (one or both chambers of Congress, depending on which Reorganization Act was in effect, voting to reject the entire plan – but the plans could not be amended). Franklin Roosevelt used such authority to move the Bureau of Public Roads from the Agriculture Department to the Federal Works Agency in 1939, and then Harry Truman used the same authority to move BPR to the Commerce Department in 1949. The Civil Aeronautics Authority was moved from being independent to being under the Commerce Department by a reorganization plan in 1940. And, fifty years ago this month, it was a reorganization plan, not a law, that moved mass transit programs from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to the Department of Transportation.

And, within Congress, consideration of these reorganization plans was not vested in the committees of jurisdiction but instead in the Government Operations Committees, which were often more of a neutral arbiter.

But the Supreme Court’s epic 1982 decision INS v. Chadha abolished the legislative veto on the grounds that it blurred the separation of powers doctrine of the Constitution. And since then, Congress has been unwilling to grant any President carte blanche for rearranging the executive branch without any way to maintain overall control of the process.

Congress did give President Roosevelt temporary reorganization authority that was not subject to legislative veto in 1933, but he didn’t take much advantage of it. And after INS v. Chadha, Congress amended the Reorganization Act so that Presidents could submit reorganization plans that would be introduced in Congress as legislation that was then put on a fast-track for expedited consideration in Congress, but that authority was allowed to expire in 1984. President Obama proposed in 2012 to revive and expand the authority that expired in 1984, but although a bill was introduced in Congress, no action was taken.

(See this indispensable Congressional Research Service report for more information on how reorganization authority evolved over the years.)

The only major government reorganization taken since the Chadha decision was the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. But that was (a) prompted by the biggest shock to the American political system since Pearl Harbor, (b) implementing the recommendations of the independent blue-ribbon panel to which the entire political class had punted the organizational problems, and (c) turned into legislative language written in the House by a new select committee chaired by the Majority Leader, so that committees that would lose jurisdiction could not hold up the bill. Absent an impetus of that magnitude, it’s hard to see how major government reorganization overcomes the inertial blocks facing it today, no matter how logical many of the ideas might be.