July 11, 2018

Federal mass transit programs were moved from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to the Department of Transportation 50 years ago this month – on July 1, 1968. That anniversary has prompted a multi-part ETW series examining the history of the federal transit program and whether it is more about transportation or more about urban development and land use. Part one of the series is here and part two is here.

Rather than upload 50-odd individual supporting documents from the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library and the National Archives to our website, we consolidated them into one big 77MB PDF compilation which can be downloaded here. Any documents mentioned but not specifically linked in the below article can usually be found in the compilation.

Initial discussions of the 4(g) study. Section 4(g) of the law creating the new U.S. Department of Transportation required the new Secretary of Transportation and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to:

…jointly study how Federal policies and programs can assure that urban transportation systems most effectively serve both national transportation needs and the comprehensively planned development of urban areas. They shall, within one year after the effective date of this Act, and annually thereafter, report to the President, for submission to the Congress, on their studies and activities under this subsection, including any legislative recommendations which they determine to be desirable. [They] shall study and report within one year after the effective date of this Act to the President and Congress on the logical and efficient organization and location of urban mass transportation functions in the Executive Branch.

-Public Law 89-670, October 15, 1966.

However, the Secretary of Transportation couldn’t do anything before he was nominated and confirmed for the job and before the effective date of the Act, which would wind up being April 1, 1967. So the joint DOT-HUD study was due by April 1, 1968. But first, DOT had to be stood up and personnel had to be appointed.

President Johnson nominated Alan Boyd, Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation (who had been instrumental in forming and selling the bill creating DOT) as Secretary of Transportation, and he was easily confirmed early in 1967. Boyd reports in his memoirs that there were only two senior DOT appointments that he did not get to choose himself and were instead picked by the White House – the Under Secretary (what is now called Deputy Secretary), Everett Hutchinson (a friend of President Johnson from back in Texas), and the General Counsel, John Robson (the college roommate of senior White House aide Joe Califano – Robson, a Republican, would later be called back to Washington under President Ford by a high school classmate, White House chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld, to run the Civil Aeronautics Board).

(Of Hutchinson, Boyd later wrote that “I liked Everett, but discovered he was ineffectual. I eventually went to the president and told him to give Everett a medal or something but get him out of the department. He did…” Later on in mid-1968, Robson replaced him.)

The DOT Act created five Assistant Secretary of Transportation slots. One was designated by law as Assistant Secretary for Administration, which went to Alan Dean, who had been a Bureau of the Budget analyst from 1947-1958 and then the top admin officer at the FAA since then and who Boyd called “the consummate bureaucrat.” The responsibilities of the other four were not set in statute but were left up to Boyd. He said in a December 1968 oral history interview that the first two were easy to define – Public Affairs (which went to Paul Sweeney) and Research and Technology (eventually going to Frank Lehan). The third became Policy Development, which went to Cecil Mackey, who Boyd brought with him from Commerce.

In retrospect, what Boyd said in his 1968 oral history about the fourth Assistant Secretary slot is interesting:

…we got into the question of a fourth assistant secretary – what should his functions be, and we were quite enamored of the idea that we ought to have an Assistant Secretary for Urban Affairs, feeling quite rightly that this was going to be the area of greatest concern and greatest impact. And also realizing the there was no good coordinating mechanism short of the Secretary for relationships between highways, mass transit, and airports, and airport access, and things of that nature. And after we kicked that around for quite a while, we decided we couldn’t afford to do that because it would be presumptuous as all hell in view of the fact that the urban mass transit was over in HUD, and we were gearing up to take it away from them…I came to the conclusion, supported by the task force advisers, that it just would be very poor taste to try to do that at this stage of the game.”

-Alan Boyd, December 1968

Instead of Urban Affairs, Boyd made the fourth AS job International Affairs and gave it to Donald Agger. Other senior DOT staff included former Budget Bureau analyst Paul Sitton (Deputy Under Secretary), former Budget Bureau analyst Gordon Murray (Special Assistant to the Secretary for Special Projects), and the three modal administrators – William “Bozo” McKee (FAA), Lowell Bridwell (FHWA), and Scheffer Lang (FRA) (future founder of the MIT Center for Transportation Studies).

On the other side of the struggle, trying to implement the (fairly new) urban mass transit programs at the (fairly new) Department of Housing and Urban Development were the Cambridge All-Stars:

- HUD Secretary Robert C. Weaver (B.A., M.A., and Ph.D., all from Harvard);

- HUD Under Secretary Robert C. Wood (a B.A. from lowly Princeton but with two Masters degrees and a Ph.D. from Harvard, who was head of the political science department at MIT until joining HUD);

- HUD Assistant Secretary for Metropolitan Development Charles Haar, a professor at Harvard Law School (and HLS class of 1948) and a national expert in land use law and urban revitalization; and

- HUD Deputy Assistant Secretary for Metropolitan Development Peter Lewis (with an A.B., a M.A. and a M.B.A. all from Harvard).

While the bill creating DOT was being debated in Congress in 1966 and while the preparation for the new Department to be operational took place in 1967, HUD was busy implementing and expanding the mass transit program. Under Secretary Wood later recalled in an oral history interview that “In that year Charlie Haar activated a program, pushed it forward on many fronts, shifted it, gave it a social context with his buses and R & D and what have you, and became strongly persuaded that it [would] flourish in HUD.”

Scheffer Lang, who had known Wood and Haar at MIT and who had previously worked at HHFA, said in his own oral history interview that:

When the Department of Housing and Urban Development was set up, the breach between [the highway program and the mass transit program] was opened significantly, in part due, I’m sure, to the conviction on the part of Assistant Secretary Haar that the highway people, professionals and these special interest groups behind the highway program, were unreconstructable. They would never willingly participate in the development of a genuinely integrated urban transportation program; that they were beyond education on the larger problems of the urban areas; that they were insensitive to the impact of highway development on urban development; and that the only sensible course was to take as much authority and responsibility away from the Bureau of Public Roads or anything that had anything to do with the Bureau of Public Roads as possible.

This is not a view which I share, and I have discussed this on occasion with Charlie Haar, but more importantly it is not a politically practical view, because the highway interests and the highway program have far too much strength in this country to be shoved out of urban transportation development. The only practical course is to bring them into the larger job of urban development and urban transportation development, not to try to push them out of it.

-Scheffer Lang, oral history interview, 1968

Initial negotiations. Shortly after formally assuming office, in early April 1967, Boyd met with Secretary Weaver and they agreed to appoint negotiators to discuss the scope of the joint study required by section 4(g) (Gordon Murray for DOT, Charles Haar and later Peter Lewis for HUD). Murray and Haar had produced a two-page scope document by June 8.

Boyd held a senior staff meeting on the morning of June 20 to discuss the matter and later that day then wrote a memo to participants asking them for their views on two issues: how transit programs should be divided between DOT and HUD organizationally, and what the relationship between organization and policy would be.

Boyd’s memo noted that “The staff of the General Counsel have tentatively found that the separation of these two requirements in the text of the Act does not require that they be met by separate reports. This means that it is to be determined on the basis of tactical and policy objectives whether they are handled together or separately.”

Responses trickled in from June 22-26 and revealed significant disagreements among Boyd’s team. While everyone agreed that the actual grant-making, grant oversight, and technical assistance side of urban mass transit would be better served at DOT, some staffers favored giving HUD complete control (Murray, Sweeney) or at least a veto (Dean) over all urban transportation planning, including highways and airports. But others (FHWA, Robson) favored taking the entire program and planning away from HUD.

However, everyone except Murray generally agreed that the organizational issues needed to get settled before the policy analysis.

Negotiations between DOT and HUD continued at the staff level. On July 6, 1967, Murray wrote a file memo indicating that HUD was delving into much more minute details than he had anticipated but that the meeting “provided the best evidence so far of real activity on the part of HUD to advance the Section 4(g) studies and report” and that having Secretary Boyd go over the head of the staff straight to Secretary Weaver might upset things.

On July 19, the senior DOT staff held a meeting (memorialized in a subsequent Murray memo on July 25) and discussed a two-part strategy: have Boyd approach Weaver, “at least for tactical effects, with some simple overall solution of organizational problems” that was so biased towards DOT that Weaver would immediately complain to the White House. At the same time, DOT would already have prepared “a somewhat more sophisticated solution of organizational problems” than had been proposed to Weaver to give to the White House once Weaver called them in.

At the same time, Alan Dean was thinking beyond whether or not DOT would win the battle with HUD and looking at where urban mass transportation responsibilities might fit within DOT. In a July 26 memo to Murray, Dean suggested putting transit under the Federal Railroad Administration: “If the Railroad Administration is ever to achieve its full potential within the Department, it needs to be given primary responsibility for all programs which place a heavy or major reliance on track-using vehicles” and since they anticipated most mass transit aid under the 1964 UMT Act would run on rails, this was the logical place.

Dean dismissed the idea of putting transit into the Federal Highway Administration because “mass transit systems of the kind being aided under the Urban Mass Transportation Act would be overshadowed by the more generously financed and better established highway programs.” He also indicated that creating a new entity for all urban transportation (highways, transit, and maybe airports as well) would “be disruptive to the Department, would run counter to its dominant approach to organization and administration, and is unnecessary to achieve the coordinated administration of urban transportation programs.”

In early August, DOT received a long-awaited report on the general issues from an outside academic consultant, Richard Warner. The report drew a distinction between two types of Cabinet agencies, the “line department” like DOT, which had operating authority for the things it was expected to coordinate, and the “umbrella” department like HUD with a much broader, coordinating role.

Warner also warned that “It would be unfortunate if the transfer of urban mass transit programs resulted in yet another interagency committee or mutual veto power…DHUD concurrence in individual projects is inconsistent with the concept developed in this paper of DHUD as an umbrella department. After mass transit programs are transferred, DHUD’s posture with respect to individual projects should be that of a Presidential staff agency – reviewing (usually after the fact), kibitzing, criticizing, persuading, occasionally escalating a dispute to the President, but not formally vetoing.”

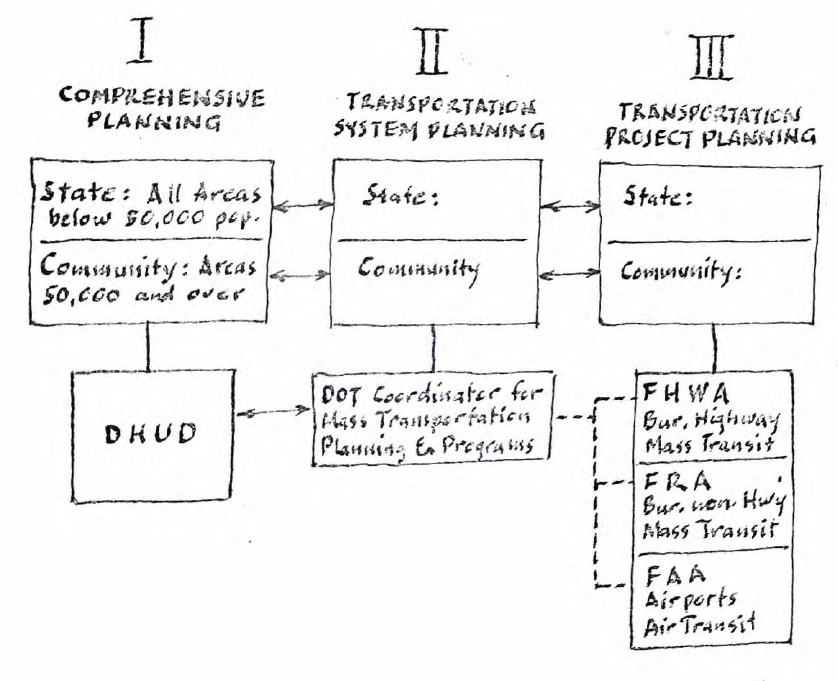

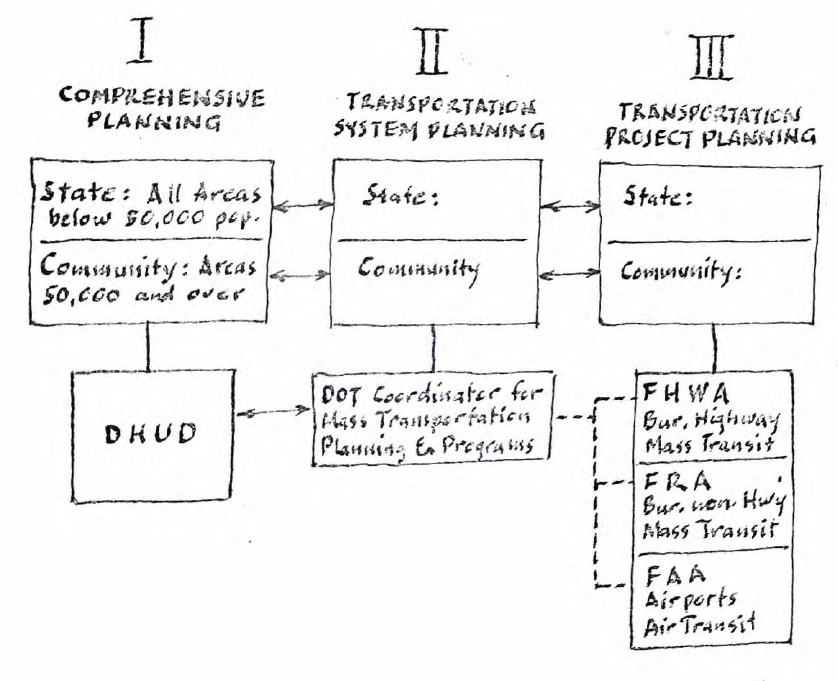

By August 21, Murray had distilled the consultant’s paper and other documents into his own draft 31-page DOT position paper. It included the following conceptual division of the issue:

With respect to urban transportation (as with all transportation, whether privately or publicly sponsored, by whatever level or combinations of government), the Department of Transportation identifies the following basic functions:

- comprehensive planning

- system planning

- project planning

- research and development

- capital investment

- administration and operations

The paper defined “comprehensive planning” as including “land use planning and the formulation and adoption of policies to implement such plans, including decisions on the location of airports, transportation corridors, public parks, schools and hospitals, sewage systems, etc. The comprehensive planning process will entail surveys of existing land use (industry type, residential density, etc.) and also forecasts of land use, reflecting effective employment of zoning, taxing and other land use policy instruments.” It also noted that “Comprehensive planning of this order is not generally achieved at the present time” and noted that the fact that so much of the money available for statewide planning flowed through federal highway dollars was part of the problem.

The staff paper concluded that all federal responsibility for comprehensive planning should be located at HUD through greatly augmenting HUD’s existing comprehensive planning grant program under section 701 of the Housing Act of 1954 (which at the time was giving out over $20 million per year in planning grants to cities) but that the planning process “should be under strictly local control and that it should be carried out by a comprehensive planning agency – areawide, whatever the area may be.”

But below the comprehensive planning level, the staff paper suggested giving DOT control over everything else. System planning would be coordinated by “a staff officer responsible to the Secretary of Transportation” across all modes. Project planning, where appropriate, would be approved by whatever modal administration was providing funding for the project (which for all transportation projects would be DOT). R&D for mass transit would also be at DOT, since it was “the intent of Congress that an integrated functional approach be followed.” All federal capital assistance for urban transportation projects would be at DOT, and since there was no direct federal operation of urban systems at the time, that wasn’t really an issue.

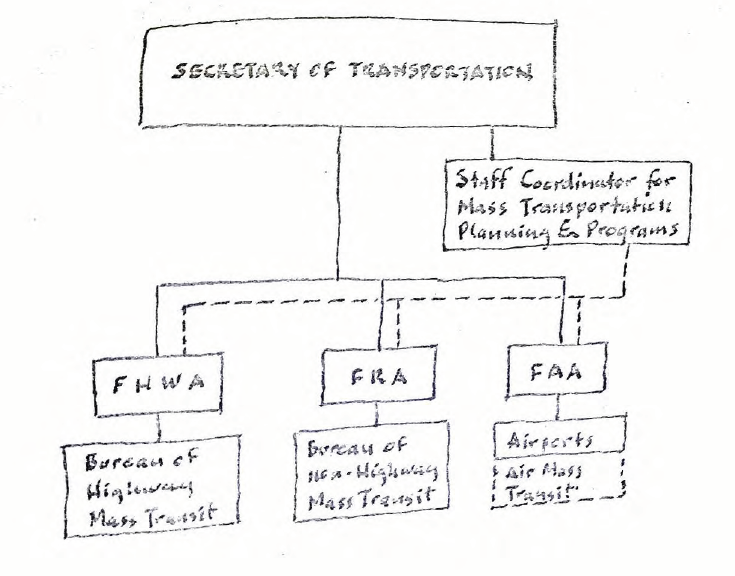

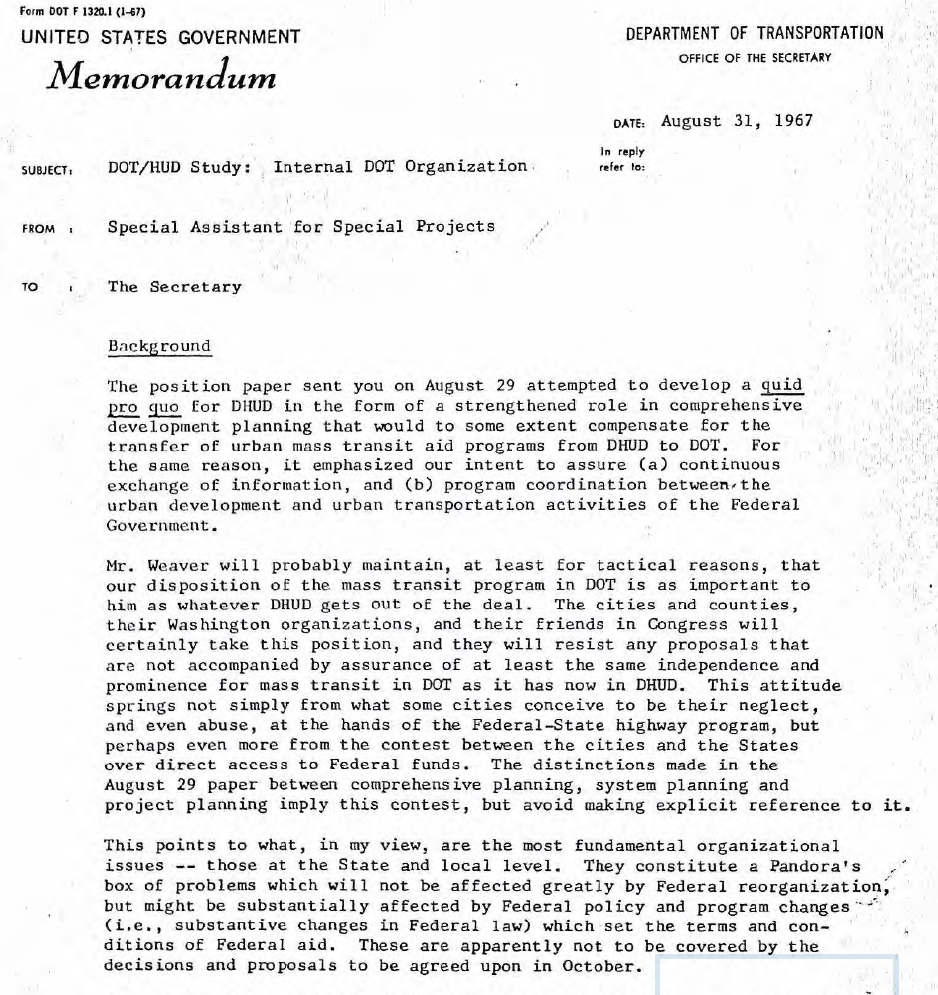

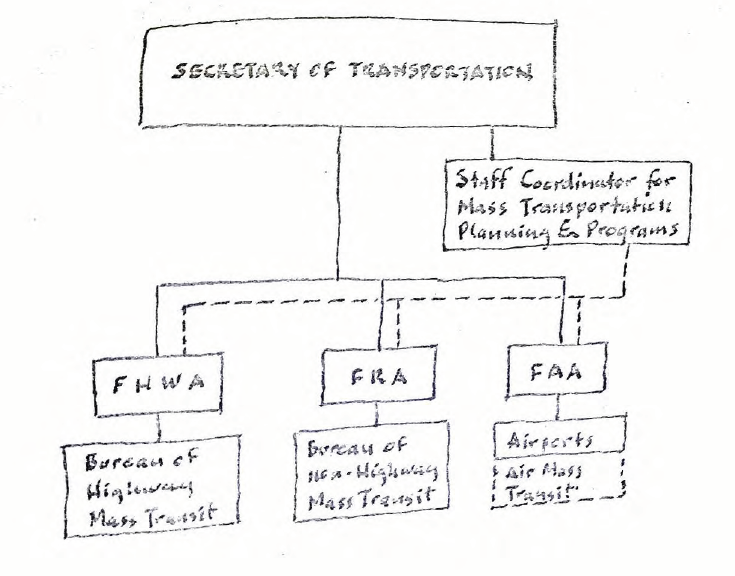

Murray’s paper included organizational charts for DOT and for the proposed planning process:

By August 28, Murray had slightly revised the position paper after receiving responses from his colleagues, principally to remove references to how mass transit would be organized within DOT, since (a) the paper was going to be going outside DOT and be given to HUD, and (b) there was not yet a staff consensus within DOT on the issue.

In an August 29 cover memo to Secretary Boyd, Murray emphasized the sensitive nature of how transit would be organized within DOT:

Members [of the internal DOT task force] generally agreed that Secretary Weaver will want to be assured that the integrity of the mass transit program will not be impaired by subordination – the fear that led to its being placed in HHFA rather than Commerce in the first place. Local interests will be even more insistent on this point.

I urge that you be prepared to give him this assurance by indicating that DOT’s organization will be adjusted to give urban mass transit a prominent place.

-Gordon Murray, August 29, 1967

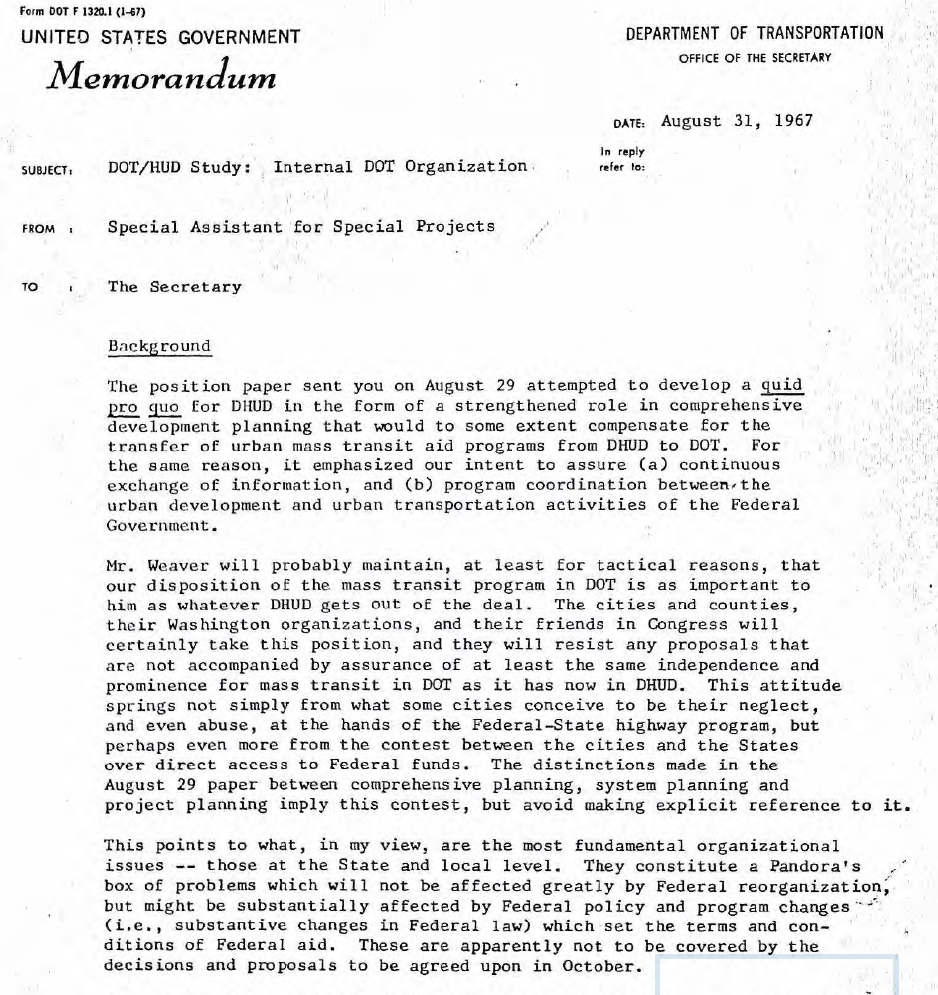

Murray sent Boyd another memo on August 31 emphasizing how the increased HUD role in planning was a political quid pro quo for giving up transit, and emphasizing how important the issue of the bureaucratic location of transit programs within DOT would be:

Murray suggested that Alan Dean explore better ways to manage transit within HUD, and Boyd approved that request on September 5.

Both parties were staring down an October 1 deadline set by the White House to settle the issue themselves or have it settled for them.

DOT-HUD talks break down. A meeting between the two Secretaries on September 19 broke down on the issue of the mass transit grant program. According to a same-day memo for the record from Cecil Mackey, Boyd said that the program needed to go to DOT, but the HUD contingent “made it clear they were opposed to the transfer of the grant program to DOT. In general it was their position that the urban mass transit program was directly related to HUD’s responsibilities in the city and, even though they recognized its close relationship to transportation systems, they felt that the program should stay where it is.”

Secretary Weaver made the argument that the grant program was a necessary ingredient in HUD’s ability to get communities to do the kind of planning which was needed. Charlie Haar referred to the program in a different way stating that frequently HUD got planning functions going by means of the grease for the machinery which was provided by the mass transit grants…

Through the course of the conversation the three of us from DOT specifically challenged each of these assumption which had formed the basis of HUD’s position. There was no evidence that our positions changed their minds significantly, if at all. Another idea that seemed to pervade the statements by all three HUD officials was an equating of DOT with the historic characterization of BPR and the highway engineer.

-Cecil Mackey, September 19, 1967 memo of meeting

Mackey concluded that “the discussion led essentially nowhere” and that he thought that each department would expect the other to file its own position paper with the White House.

In an undated memo marked “Administratively confidential” that had to be from late September 1967, Boyd wrote to White House domestic policy aide Joe Califano and said that he and Weaver would not meet the October 1 deadline and that “It appears, therefore, that the mediation of the President or his executive staff will be required…”

In his memo, Boyd reiterated the earlier DOT position – that HUD be given control over comprehensive planning (and that it be beefed up with more legal authority and financial resources) and that DOT get everything else. But Boyd also promised that DOT would “establish a Mass Transportation Assistance Administration as an independent operating agency” within DOT to have the same status as FAA, FRA, FHWA and the Coast Guard, with its Administrator having direct reporting authority to the Secretary.

Since the urban mass transportation division at HUD had to report to Assistant Secretary Haar and was not a “direct report” to Secretary Weaver, Boyd noted in the memo that his plan would give transit “greater visibility and status than it now has in HUD.”

On October 6 and 7, DOT and HUD submitted the summaries of their positions and arguments on the transit issue to the White House.

DOT Arguments

|

HUD Arguments

|

| “Urban mass transit is one, inseparable element of the urban transportation system in which DOT is already and will continue to be the most heavily involved Federal agency from a financial investment, program and mission statement.” |

“Mass transportation is a leading factor shaping the orderly and sound growth and development of cities and suburbs. While it is difficult to conceive of urban expressways as separated from an interstate system, this is not true of urban mass transportation. The latter rarely has significant impact beyond the metropolitan area and is inextricably involved in the urban development process.” |

| “We regard all transportation as a function which should serve, not govern, the social, economic and other environmental goals identified in Government programs and the comprehensive planning process.” |

“Mass transportation is part and parcel of any attempt to solve the problems of lower income groups, particularly in ghettos, and more specifically the problem of getting slum residents from where they live to where they can be employed.” |

| “Effective system planning for urban transportation problems requires that all phases of transportation should be administered by a single agency so that the full range of investment options and trade-offs can be most effectively perceived by those responsible for local urban planning and those responsible for decision regarding Federal investment in transportation.” |

“Mass transportation gives strength to the whole urban comprehensive planning process. Planning without program authority implies an advisory and consultative role – a role that is ineffectual for a Department which has urban coordinating functions…with a grant program for urban mass transit, HUD has not only been able to secure compliance with planning requirements; it has also been able to develop workable and meaningful plans.” |

| “If transferred to DOT, the urban mass transit program would be organizationally independent of other Administrations in the Department. We would plan to establish the mass transit program as an independent element reporting to the Secretary. In this posture we would be able to insure both the continuity of the program and coordination with all other transportation programs in the Department and with the efforts in the Office of the Secretary designed to accomplish the maximum consideration of social, economic, aesthetic and other environmental values in all of the Department’s programs.” |

DOT’s “responsibilities involve the Bureau of Public Roads (the largest program element of the Department) with the powerful and organized State highway departments and the potent American Society of State Highway Officials. Accordingly many urban interests take the view that it is extremely risky to try and tame the highway program by associating the administration of mass transit with that of roads…These and others (some of whom are supporters of mass transit in Congress) would regard the transfer of mass transit out of HUD as a diminution of Administration emphasis on city transportation needs in particular, and of city social development and ghetto programs in general.” |

After both DOT and HUD had submitted their cases to the White House, there was silence for a month while the Bureau of the Budget analyzed the issue. On November 4, the career staff at Budget produced a staff paper that summarized the pro and con arguments put forth by each department but concluded, “On balance, we conclude that the urban mass transportation programs should be transferred to DOT.”

It is impossible not to recognize that DOT already has the dominant role in shaping urban mass transportation systems. At the Federal level, its highway, airport, and high-speed ground transportation programs, particularly the former, far outweigh the mass transportation program. What DOT’s programs do, not what HUD’s program does, determines primarily the nature and shape of urban transportation systems. HUD’s role and leverage are limited. Put bluntly, DOT can pave HUD over.

-Bureau of the Budget staff paper, November 4, 1967

The staff paper also recommended various kinds of increased DOT-HUD coordination. The 16-page staff paper was then supplemented by a four-page BoB summary memo which added that one reason they were recommending transfer of transit to DOT was because of “the existing proper climate in the Secretary’s office in DOT – that is, a perspective of the service nature of transportation and its role in community development…” To translate that last part, you need to read the oral history interview of Charles Schultze, who was Budget Director in 1966-1967, who said that Boyd had been “trying to do what makes sense for the country in terms of transportation, rather than just simply getting a bigger empire for this component or that component…looking ahead at major transportation requirements, not to be swept off his feet by lobbying from below and outside for particular interests, being willing to balance them all…”

Then on November 6, two of the more politically attuned people at Budget, Charles Zwick and Fred Bolen, forwarded the staff study upwards with their own recommendations. Both men said that “From the narrow point of view of a technically well-executed mass transportation program, we both believe that it should be transferred to DOT” but that the loss at HUD would “weaken an already weak Department.” Zwick recommended that the program be moved to DOT and Bohen recommended leaving it at HUD, but both men said their analysis did not take into account the politics of the move, which “may be formidable.”

Sometime in late November, Califano and Budget Director Schultze decided they agreed with DOT and met with Weaver and Boyd to give them the news. According to Califano, “Weaver said he would go along, but wanted me to talk to Charlie Haar to soften the blow and give [President Johnson] his arguments before a decision was made.”

President Johnson decides. On December 1, Califano sent President Johnson a decision memo on the issue. After laying out the basic facts and an outline of the arguments on both sides, he noted that “After numerous unproductive conferences during summer and early fall, it became clear that Weaver and Boyd would not work out a settlement of this issue between them. But both agreed that we needed a settlement of the issue before the report was done so that we could go to Congress with a unanimous view.”

Califano then wrote that he and Schultze “agree with Boyd on the merits of the issue” but that it would be necessary to work out detailed coordination procedures between DOT and HUD and that “Politically, a decision to leave Mass Transit in HUD or to move it to DOT will be controversial on the Hill, in City Halls and State Capitals and among client groups.”

At some point, President Johnson obviously approved Califano’s proposal, and Boyd presumably was informed but ordered to keep it quiet, because he sent a December 6 memo to senior DOT leaders asking them to undertake, “with as limited staff as possible, preparation of a paper setting forth all the feasible alternatives for the organizational structure to handle the urban mass transit program within the Department.” Boyd also told his team to bear in mind that cities and urban interests did not wish to see the prominence of the program downgraded and that they held a “general animosity toward the highway fraternity.”

A meeting was convened by Under Secretary Hutchinson on December 11, after which everyone was supposed to submit their ideas in writing to Alan Dean. Over the December 11-13 period, everyone submitted short memos with their suggestions to Dean – except FHWA Administrator Lowell Bridwell, who tried to go over Dean’s head with a memo straight to Secretary Boyd stating that “If this program is transferred to DOT there are strong reasons for assigning it to the Federal Highway Administration.”

(Dean later said of Bridwell in an April 1969 oral history interview that Bridwell “was in constant warfare with the Assistant Secretary for Policy Development and with the Deputy Under Secretary. He got to the point where he wouldn’t handle anything with them except by formal memorandum. He wouldn’t allow his staff to talk to anybody in the Office of Secretary except with his clearance. Lowell overreacted, in my judgment, but in all fairness there were people who were trying to run the highway program for Lowell out of the Office of Secretary. And it was neither black nor white. The Administrator in this case was pretty hard to work with, but he had provocation.”)

Dean assembled all of the suggestions into a memo to Secretary Boyd on December 16 that presented him with the pros and cons of three alternatives:

Alternative 1 – Assigning Responsibility to an Official in the Office of the Secretary. The Assistant Secretary for Policy Development, the General Counsel and the Federal Railroad Administrator would establish a position of Assistant Secretary, or utilize the position of Deputy Under Secretary, as the focal point of both staff and line direction in matters relating to the administration of the urban mass transportation program and urban transportation generally. As his second choice (that is, if the program cannot be placed in FHWA) the Federal Highway Administrator would choose this alternative, except that he would create a post of Under Secretary for Urban Mass Transportation. This alternative avoids the creation of a new operating administration for mass transit…

Alternative 2a – Establishing an Urban Mass Transportation Administration. This option, as well as Alternative 2b, as described below, contemplates the establishment of an Urban Mass Transportation Administration headed by an Administrator reporting directly to the Secretary. Alternative 2a is distinguished from 2b in that the former makes no specific adjustments in the Office of the Secretary and envisages each of the present functional OST officials relating to the Urban Mass Transportation Administration in much the same manner as he now relates to the exiting administrations. The Deputy Under Secretary, the Special Assistant to the Under Secretary, the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Special Programs, the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, the Federal Aviation Administrator and the Assistant Secretary for Administration all urge that a separate administration be established for urban mass transportation, but several of these official specifically recommend adjustments in the Office of the Secretary as will be indicated in the discussion of Alternative 2b…

Alternative 2b – Establishing an Administration with Special Arrangements in the Office of the Secretary. The Deputy Under Secretary, the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Special Programs, the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, and the Assistant Secretary for Administration, all support the establishment of an Urban Mass Transportation Administration for the reasons presented above, but they also feel that specific provision for leadership and coordination in urban transportation generally must be made simultaneously in the Office of the Secretary. It is felt that this can be done through a number of devices, but the preponderance of opinion is that either an Assistant Secretary (including an additional position if need be) or the Deputy Under Secretary should be charged with staff leadership in matters of urban affairs and urban transportation…

-Alan Dean memo of December 16, 1967

Dean’s memo rejected out of hand the idea of giving transit to FHWA or of creating an Under Secretary for Urban Transportation. The final recommendation was Alternative 2b and using “the present position of Deputy Under Secretary as the focal point of Department-wide policy and program leadership and coordination in urban transportation matters.”

But during a staff meeting on December 19, that approach was modified and Alternative 2b was dropped, perhaps because the group found that creating a new modal administrator to advocate for urban issues and creating a new urban advocate in the Office of the Secretary was overkill (and because juggling responsibilities in OST meant that someone would lose, someone would gain, and Congress might have to be asked to amend the law and give them more personnel, which was always a tough sell).

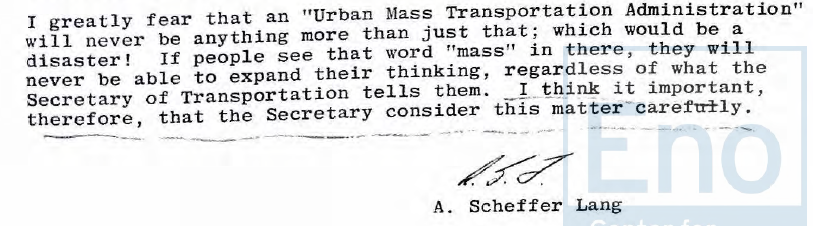

And Shef Lang wrote to Dean the following day that he didn’t like the name:

Dean then sent a modified version of his earlier memo to Secretary Boyd on December 26, but with Alternatives 2a and 2b merged into a single Alternative 2 – establishing a UMTA, with the Secretary having the option of “charging an Assistant Secretary or the Deputy Under Secretary with leadership in matters cutting across operating administrations.” The memo recommended Alternative 2, and Boyd approved it.

Sometime around New Years, HUD Under Secretary Wood sent an “Eyes Only” memo to Joe Califano entitled “Basic Points for a Proposed New HUD/DOT Relationship. It called for an expansion of HUD’s existing section 701 planning grants (financially and in legal scope) and for HUD to “assume responsibility for setting standards, guidelines, and reviewing the planning work programs of State Highway Departments – in effect, leveling requirements on the location and impact of transportation in the urban areas.” It also called for HUD concurrence (which means veto power) over transportation grants or loans for urban areas.

Boyd and Wood had a meeting on January 2 to discuss the memo, which Boyd memorialized in a file memo. Boyd agreed to most of Wood’s requests, in theory, and said that “we agreed to the ‘lead agency’ principle with HUD having the lead on planning and impact and DOT having the lead on research and operations. We further agreed that collaboration while essential should be limited to matters of importance and should not devolve into any sort of nit-picking.” Boyd then wrote that he had proposed to the White House that they move ahead with the transit-to-DOT transfer via a reorganization plan.

The following day, Boyd sent a memo to Joe Califano telling him what he and Wood had agreed to, proposing to make the move via a reorganization plan instead of a change in law, and beginning a notification campaign to Congress and stakeholders prior to the State of the Union speech.

Importantly, Boyd noted that he had not discussed the use of a reorganization plan with HUD. This was critical because a reorganization plan could not be used to make the necessary changes in law for some of the things HUD wanted, like a beefed-up 701 program or a statutory role in transportation planning. Only a new law could accomplish those things. However, mass transit and highway and housing bills were all scheduled for reauthorization in Congress in the upcoming year.

On January 10, the Budget Bureau produced a one-page summary of the reasons why a reorganization plan was superior to a change in authorizing law as a means effecting the move of transit from HUD to DOT. Those reasons (not verbatim) were:

- Reorganization plans automatically took effect in 60 days unless vetoed by either chamber of Congress, while new bills could be killed in committee or filibustered on the floor.

- Reorganization plans were not subject to an amendment and had to be accepted or rejected in their entirety.

- Since appropriations had already been made and staff hired and contracts let, it was easier to transfer those resources administratively than through a new law.

- Reorganization plans were used in Congress often.

- Reorganization plans were in the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Government Operations Committees, which were generally sympathetic to reorganization plans to promote efficiency. A law making the change would have been referred to the Banking and Currency Committees, which might not like the idea.

Secretaries Boyd and Weaver met on January 12, 1968, and Weaver agreed to go the reorganization plan route. The two men set up a schedule of Congressional and stakeholder notification appointments. At least one of the notifications did not go well – on January 23, House Banking and Currency Committee chairman Wright Patman (D-TX) and several committee members wrote to President Johnson to say that “the preponderance of the membership of the House Committee on Banking and Currency strongly opposes this misguided proposal…we submit, in the strongest possible terms, that our Committee and its Subcommittee on Housing and the Department of Housing and Urban Development should never be deprived of the jurisdiction and management of a program which we first launched and have since nurtured, and a program which we hope to gradually expand and improve toward the ultimate objective we all seek of an urban America with the vitally needed fast, low-cost rapid transit it must have to survive.”

(Shef Lang wrote to Boyd a few weeks later to explain that “Patman is, in fact, concerned about a possible loss of jurisdiction. Put another way, we must worry about his ego. It was suggested that Patman will want assurance from Speaker McCormack, and concurrence from the White House and the Department that he will retain substantive jurisdiction over the urban mass transportation programs. I have been advised that the message should also get through to him that this would give him a look in on still another department, something which would further enhance the scope of his committee’s activities.” Patman did not have to worry – the Banking Committee would keep jurisdiction over mass transit until the House voted in October 1974 to give jurisdiction to Public Works instead. But Patman was thrown out of his chairmanship by a restive Democratic Caucus three months later so it didn’t really matter to him anyway.)

Results of the advance outreach to other legislators and interest groups was summarized in a February 1 memo from Boyd to Califano and was largely positive. This bit is interesting: “Senator Harrison A. Williams – Stated that the function was really about transportation and should be in DOT. His staff expressed concern about Pete losing committee jurisdiction. Williams did not seem perturbed.” (Recall that Williams had, five years prior, argued against placing responsibility for mass transit with the other federal transportation programs then at the Commerce Department, saying that “it would be a desperate mistake to take from [the housing agency] the opportunity to weave the circulatory system of transportation system into other urban areas concerned.”)

Defining the new roles. On January 25, Secretaries Boyd and Weaver and their staffs met again, and turning their general agreement into specific commitments was proving difficult. In particular, the issue was what should go in the text of the reorganization plan (which had the force of law in many but not all respects – see this invaluable Congressional Research Service report for the rules in effect in 1968). According to a DOT file memo, Weaver wanted an amendment to 23 U.S.C. §134 (the authority enacted in the 1962 highway bill requiring FHWA to certify that highway projects in urban areas were part of some kind of planning process) in the reorganization plan to transfer that approval authority to HUD.

According to the memo, Boyd “indicated that inclusion within the reorganization plan of language transferring Section 134 responsibilities to HUD was a sensitive political issue. He believed it would be extremely unfortunate if such a proposal were adopted since it could trigger counter effort by highway interests to thwart DOT/HUD efforts to strengthen the role of comprehensive community planning in guiding highway transportation planning. Such efforts were not to be discounted as idle threats.” Boyd instead proposed cementing the new DOT-HUD relationship in a memorandum of understanding (MOU). The HUD contingent agreed.

However, talks between the two agencies then stalled. A meeting was called by the White House for 5 p.m. on Thursday, February 1. White House aide Fred Bohen wrote a memo to prepare Joe Califano for the meeting. The memo said that there were to major issues that needed to be decided. One was Chairman Patman (Weaver was leveraging Patman’s jurisdictional opposition into a need for a solid quid pro quo to be given to HUD to keep Patman from fighting the transfer). The other issue was:

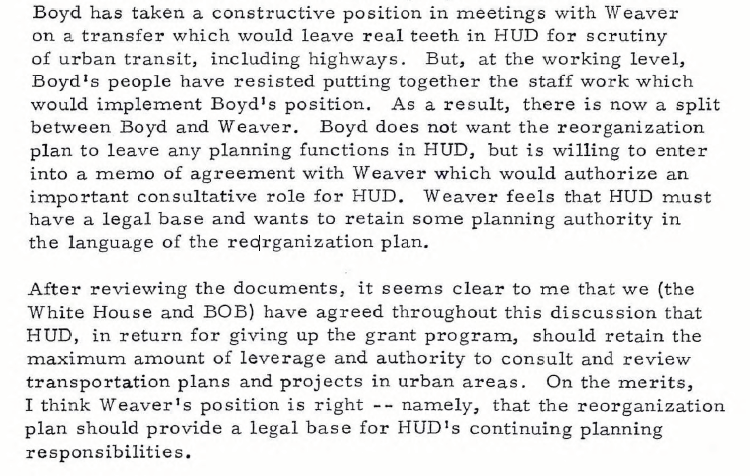

Also in anticipation of the big White House meeting, HUD Assistant Secretary Charlie Haar was trying to reinforce his own message to Secretary Weaver one last time – that any HUD authority not nailed down in some kind of legislative or force-of-law language would be gone forever:

On February 3, Dean told Boyd that on the day after the meeting, he and his counterpart at HUD, Dwight Ink, had reached agreement on a joint issues paper (dated February 2) and that the only area where “a continued divergence of views is reflected” is where HUD continued to demand statutory language in the reorganization plan giving them sole authority certain determinations for transit project approvals (veto power over projects if HUD felt they were not properly in the comprehensive plan). But Dean reported that “because Secretary Weaver did not push this point in the White House meeting on Thursday, both Dwight Ink and I assume that BOB will make no effort to provide for a reservation of these determinations and that, instead, the DOT proposal of handling the relationships by Memorandum of Agreement will prevail.”

The Budget Bureau then took over the writing of the reorganization plan, and a draft dated February 13 was circulated. On the following day, HUD sent a protest letter to Budget, saying that “the Secretary continues to feel very strongly the Plan should include a reservation with regard to HUD’s continuing role to make the determinations as to the adequacy of programs for transportation systems as part of comprehensively planned transportation. This is both to provide a basis for our security support from the Appropriations Committee to staff for this function, and because of our reluctance to weaken the limited leverage we now have with respect to urban planning activities on which urban transportation has such a critical impact.”

HUD included suggested changes to the text of the plan, along with a supporting position paper, but to no avail. The final text of the reorganization plan (the draft dated February 19, as transmitted to Congress on February 26) overruled HUD’s objections, as shown below.

What HUD Wanted

|

Final Reorganization Plan

|

| Sec. 1(a) There are hereby transferred to the Secretary of Transportation: (1) the functions of the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 (78 Stat. 302; 49 U.S.C. 1601-1611), except that there is reserved to the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development authority under that Act |

Sec. 1(a) There are hereby transferred to the Secretary of Transportation: (1) the functions of the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 (78 Stat. 302; 49 U.S.C. 1601-1611), except that there is reserved to the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development authority under that Act |

| (i) to make determinations under sections 3(c), 4(a), and 5 of the Act (49 U.S.C. 1602(c), 1603(a), and 1604) as to the development or adequacy of programs for transportation systems as part of comprehensively planned development, and |

(ii) so much of the functions under sections 3, 4 and 5 of the Act (49 U.S.C. 1602-1604) as will enable the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (A) to advise and assist the Secretary of Transportation in making findings and determinations under clause (1) of section 3(c), the first sentence of section 4(a), and clause (1) of section 5 of the Act, and (B) to establish jointly with the Secretary of Transportation the criteria referred to in the first sentence of section 4(a) of the Act. |

| (ii) to make grants for or to undertake projects or activities under sections 6(a), 9 and 11 (49 U.S.C. 1605, 1607(a) and 1607(c) to the extent that these projects or activities primarily involve relationships between urban mass transportation systems or technologies and other urban planning, housing or development objectives. |

(i) the authority to make grants for or undertake such projects or activities under sections 6(a), 9 and 11 of that Act (49 U.S.C. 1605; 1607a; 1607c) as primarily concern the relationship of urban transportation systems to the comprehensively planned development of urban areas, or the role of transportation planning in overall urban planning… |

By February 20, Boyd was reporting to Califano the list of interest groups and big city mayors who had agreed to send telegrams to the White House supporting the move to DOT once President Johnson made the decision public. Johnson did so on February 22 as part of his special message to Congress on cities, and formal transmission of the reorganization plan took place on February 26. The formal joint DOT-HUD study required by section 4(g) of the DOT Act supporting the move of transit to DOT was not sent to the President until February 28 but it was backdated to look like it was sent February 19, before the public announcement.

Congress considers the plan. Congress now had 60 days in which to reject Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1968 or else let it take effect. That was 60 legislative days, which excluded recesses, meaning that the plan was to take legal effect on May 7 unless rejected by either chamber. (Though the real effective date in section 6 of the plan was “the close of June 30, 1968 or [the day the plan took legal effect after 60 days], whichever is later.”)

On March 2, Sen. Pete Williams (D-NJ), the father of the federal mass transit program, took to the Senate floor to announce his support for the move (see p. 4900 here): “I do not see how planning for urban transportation can take place outside the context of the national planning effort now underway within the new Department [of Transportation]. At the same time, such planning must necessarily take place within the context of the comprehensive planning for our urban areas by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The proposal before us very effectively combines these concepts and for that reason it has my support.”

As luck would have it, the subcommittee of the House Government Operations Committee with jurisdiction over reorganization plans was chaired by Rep. John Blatnik (D-MN), who was also the second-most-senior Democrat on the Public Works Committee. (Blatnik’s administrative assistant at the time was a young man named Jim Oberstar.) Blatnik held a hearing on the reorganization plan on April 22 at which Boyd, Wood, and the Deputy Budget Director (Phillip Hughes) testified.

The hearing featured a solid two hours of grilling by Blatnik and Reps. Benjamin Rosenthal (D-NY), Henry Reuss (D-WI) and John Erlenborn (R-IL), and the proposed relationship between HUD and DOT on project approvals was the primary subject. Blatnik said “I am not clear on how it would be put into operation; that is, I just don’t see where HUD’s authority ends and the Department of Transportation’s begins. It is pretty complicated.”

Wood replied that “in essence HUD will be the prime force in trying to encourage comprehensively effective development plans and then to see how transportation activities impinge upon them…this is a complicated business. It is clear that DOT and HUD are going to have to sit in each other’s laps in this whole series.”

Rosenthal brought up Robert Moses, alleging that DOT’s mission charge from the President was to build efficient transportation facilities and that HUD’s mission charge was urban quality of life. Both Boyd and Wood took offense to this, and tried to explain the new relationship (to be more formally spelled out in a memorandum of understanding), but Rosenthal wasn’t buying. He said that the Administration “was just playing with words. [HUD’s] role in this act will be a third-rate supporting character. They will make recommendations, and if the Secretary of DOT doesn’t like them they will reject them. They will dance the same music for 6 months to a year and after that it will be over.”

Rep. Erlenborn used the hypothetical example of Chicago wanting to extend the rail transit line to O’Hare Airport and applied to DOT for mass transit grant money:

Mr. ERLENBORN. Let us suppose the city of Chicago has not, done the job of overall urban planning that HUD thinks they should have, would HUD then have veto power over this apl)lication for assistance for the extension of a rail line?

Mr. WOOD. In effect I think it would.

Mr. ERLENBORN. I wonder if Secretary Boyd could answer that ?

Mr. BOYD. Yes, sir; I will be glad to. We are working out an agreement between our two Departments which would provide that in matters of this particular nature, the certification by HUD is a part of the approval process.

Mr. ERLENBORN. It is a requisite, then ?

Mr. BOYD. Yes., sir.

Mr. ERLENBORN. If HUD should want to veto because of the lack of planning, it would have the autihoity to do so under the plan or under your agreement ?

Mr. BOYD. Under our agreement.

Mr. ERLENBORN. It is not clear mider tle plan.

Mr. BOYD. That is right. It will be under the agreement. I think the question really would be whether or not there was a comprehensive plan. This is up to HUD to say. I am sure if the city of Chicago came in with an application and HUD said, “You don’t have a general plan,” that the city would probably want to appeal. I think the thing would work out in practice this way. We would sit down with HUD and they would indicate what was lacking. We would say, “All right, Chicago, these are the conditions. You go out and do this, that, and the other. ‘I’hen you will have a plan, and then you can come back.”

-House Government Operations Committee hearing, April 22, 1968

Boyd also told Erlenborn that DOT and HUD were still working on the memorandum of understanding spelling out the relationship and they hoped to have it ready once the plan became effective.

Two days after the House hearing, Rep. William Cramer (R-FL), a member of the Public Works Committee, said (see p. 10467 here) that he had been given a copy of the joint DOT-HUD issue paper prepared by Dwight Ink and was shocked by the authority that it proposed giving to HUD. He said he opposed “vesting in [HUD] substantial powers and authority over highway planning and construction in urban areas.” He closed by urging opposition to the plan unless the new DOT-HUD relationship on transportation project approvals was more specifically spelled out.

Cramer apparently also spoke with Secretary Boyd, because the following day, Cecil Mackey (Acting Secretary because Boyd was out of town) wrote a letter to Rep. George Fallon (D-MD), chairman of the Public Works Committee (and author of the Interstate Highway Act) saying that “I can give the Committee my assurance” that “the Secretary of Transportation [would] not relinquish any of his basic statutory responsibilities for determining the adequacy of the urban transportation planning process and approving Federal aid highway projects.” (Key word being “statutory.”)

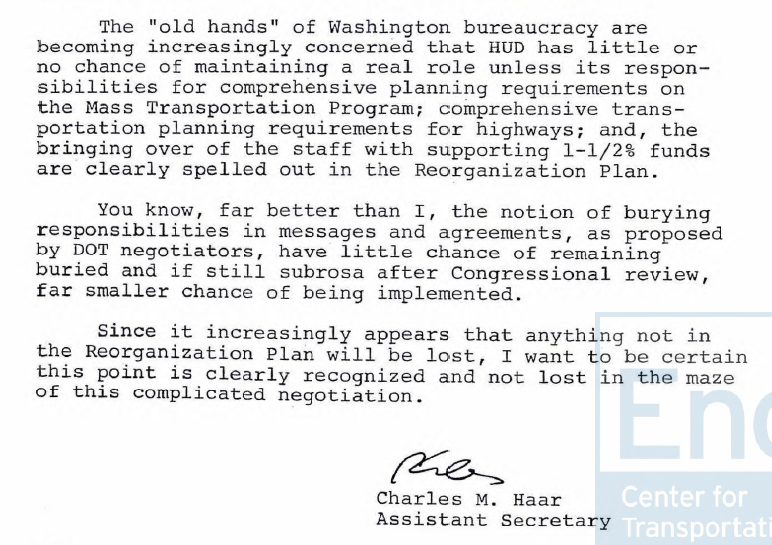

Fallon submitted the letter into the Record (starting on p. 11514 here) along with his own statement that:

No hearings were held in the Senate, but Sen. Jacob Javits (R-NY) did inquire of DOT and HUD as to their plan for their new relationship, which they answered in a May 6 letter which Javits out into the Record a few days later (see p. 13662 here). The heart of the joint Boyd-Weaver letter was this:

l. The Federal responsibility for assisting and guiding areawide comprehensive planning (including areawide comprehensive transportation planning) by local communities resides in HUD. Criteria for urban transportation system planning are to be developed jointly by HUD and DOT.

2. HUD will advise DOT whether there is a program for a unified urban transportation system as part of the comprehensively planned development of the area. This will include the adequacy of the planning process. The HUD advice would be a prerequisite for DOT making the findings required under sections 3(c), 4(a), and 5 of the Urban Mass Transportation Act. In addition, similar coordinative relationships will be established between DOT and HUD so as to harmonize the planning process required by section 134, title 23 of the Highway Act of 1962 with the comparable planning requirements of the Urban Mass Transportation Act.

3. DOT has the responsibility for determining whether individual projects are needed for carrying out a unified urban transportation system as part of the comprehensively planned development of the urban area. However, the Memorandum of Understanding will include arrangements under which DOT will first secure recommendations from HUD in the case of the projects having a significant impact on the planned development of the urban area.

-Letter to Sen. Javits from Secs. Boyd and Weaver, May 6, 1968

Neither Reps. Fallon nor Cramer nor anyone else introduced a resolution of disapproval of the plan, and it took legal effect on May 7 and was submitted to the Federal Register for publication as a quasi-law the following day.

In a March 1969 oral history interview, Alan Dean summarized why he thought DOT had won the contest:

…some of the program-oriented officials [at HUD], who were losing jurisdiction over an important program, were very unhappy. They weren’t able to stop it, however. We had an advantage. DOT is inherently a more popular department than HUD, not because it’s any more deserving, but because its programs are more popular and less politically controversial. In any clash between HUD and DOT, we can count on the bulk of the Congress being on our side, if our case is at all reasonable. We are a powerful and big department compared to HUD. You could lose the HUD in one corner of FAA. I think it has not over 20,000 people in the entire department. We have 100,000. They have a lot of money, but it is chiefly mortgage finance money and grant money. So it was an unequal contest.

We also had momentum going for us. Mass transportation sounds like transportation. We had the Bureau of the Budget on our side; we had the congressional committees on our side. Even the city organizations like the National League of Cities and the Conference of Mayors, which some HUD people thought would oppose the plan, refused to oppose the transfer. I say a few hard feelings were left among those who felt that we had gobbled up part of a sister department.

-Alan Dean, March 1969 oral history interview.

Implementing the move. Meanwhile, DOT had been at work trying to figure out the mechanics of integrating the transit program. An earlier March 21 memo from Gordon Murray to Boyd had indicated that in addition to the ongoing work on the MOU and the need to nail down which precise appropriations, projects, personnel and equipment would be transferred, they also had to figure out who would run the thing. Referencing the problems with Under Secretary Hutchinson mentioned above, Murray wrote that “If DOT receives a new Under Secretary in the near future who has strong administrative capabilities, he might well be named Acting Administrator, as the reorganization plan allows.”

President Johnson nominated John Robson to be Under Secretary of Transportation on May 8, 1968, and the Senate confirmed him on May 22, Accordingly, when the Urban Mass Transportation Administration came into existence on July 1, Secretary Boyd named Robson the first Acting Administrator. (The President eventually nominated Paul Sitton for the post on September 4, and the Senate confirmed him as the first non-acting Administrator on September 12.)

On July 12, the Director of the Bureau of the Budget signed the formal “determination order” transferring specific amounts of prior year appropriations, all new FY 1969 appropriations, specific ongoing projects and studies, 38 named personnel, and specific items of office equipment and furniture (48 desks, 33 filing cabinets, 3 adding machines, 23 typewriters, etc.) from HUD to DOT.

The memorandum of understanding between DOT and HUD took longer than anticipated. It was not ready when the new UMTA started up; instead, it was not signed by the two Secretaries until September 9 and 10, 1968. The text of the MOU promised a wide variety of consultation and cooperation between the two departments. But on the key issue of who had veto power over new urban transportation projects (signing off on the necessary determination that the project was part of a comprehensive plan), the MOU said that “HUD will assist DOT by providing advisory certifications or other advance in connection with determinations by DOT” for mass transit projects under sections 3(c), 4(a) and 5 of the transit law and section 134 of the highway code.

The MOU also provided that either party could quit the agreement upon 90 days written notice.

In his oral history interview a month later, HUD Under Secretary Wood sounded optimistic about the future of the MOU process: “What emerged [this year] was a kind of lead agency concept of HUD as principal federal presence in environmental urban development. This was what the organization plan number two in effect finally accomplished, and the agreement that came around last month confirmed it. For the first time HUD comments authoritatively and systematically on the impact of all forms of transportation in the urban condition and the highways, which I regard as very vital.”

Three months after that, in one of his own oral history interviews on January 11, 1969, Boyd was not as sanguine:

We tried to strike a compromise with HUD on [mass transit] and I think by definition compromise is a bad solution . This is proving to be a bad solution. It’s nothing critical, and it’ll work out in time, but it’s not the way it ought to be. A lot of this involves personalities . When I leave here and Bob Weaver has left, Bob Wood leaves HUD, Charlie Haar leaves HUD, John Robson leaves here, there will be a whole new set of players, and they’ll be able to work out agreements without all of the animosities which we have generated, just as a result of sort of pulling Urban Mass Transit out of HUD’s hide. And you couldn’t expect them to be very happy about it.”

-Alan Boyd, oral history interview, January 1969.

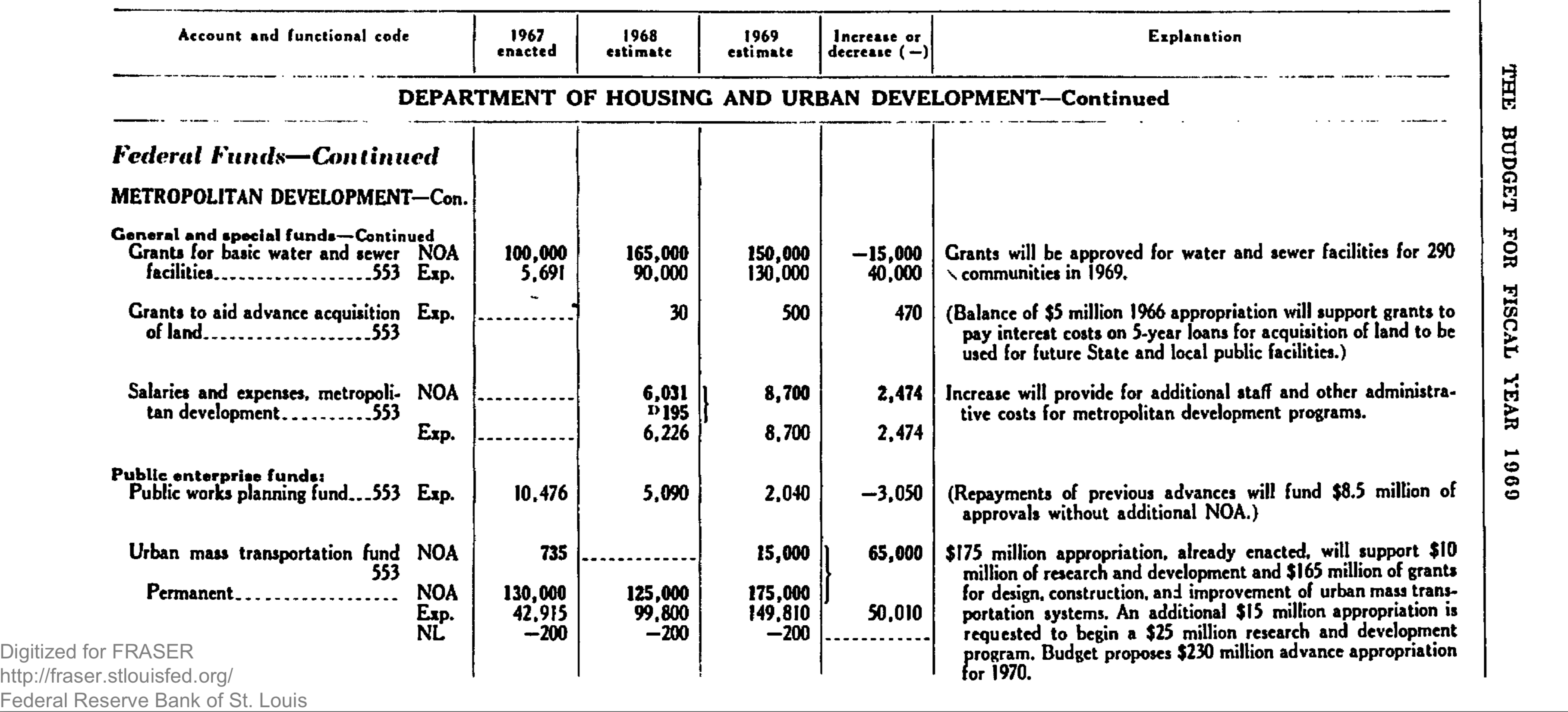

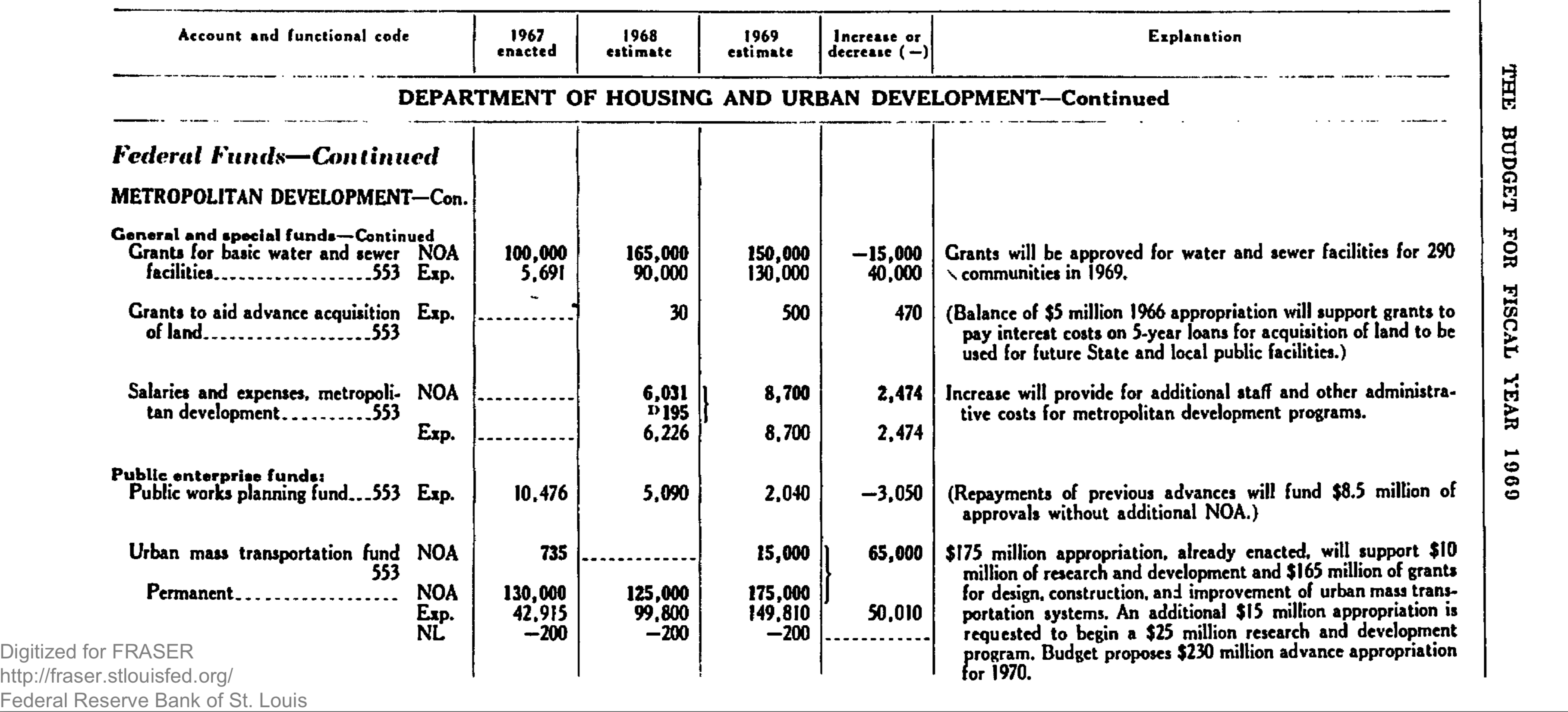

One other critical component of the move was handled by the Bureau of the Budget. When the urban mass transit program was created, in 1961, the Bureau assigned its annual appropriation to budget subfunction 553, “urban renewal and community development activities,” which was part of budget function 550, “housing and community development.” At the time the reorganization plan was proposed, the fiscal 1969 budget had just been released, and mass transit was still in subfunction 553.

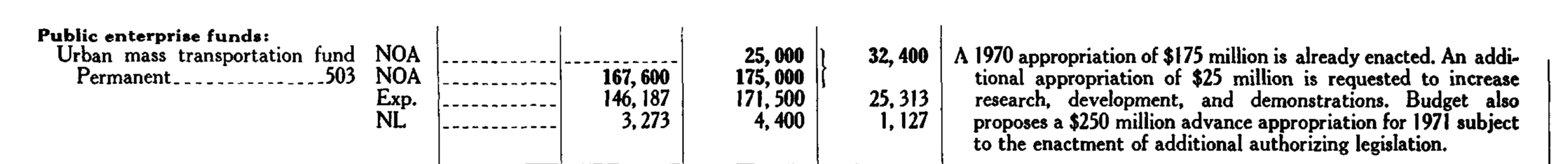

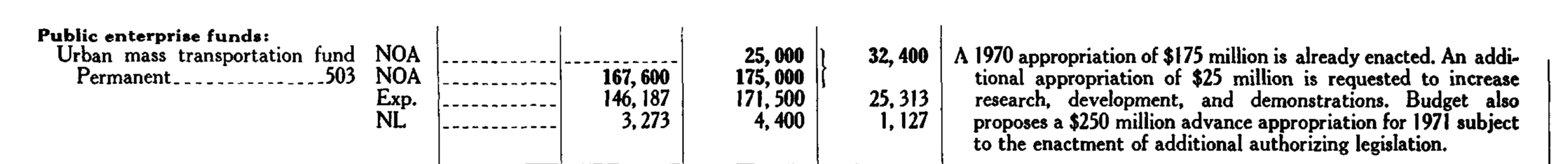

But the FY 1970 budget was prepared after the move to DOT had taken effect, and the Bureau decided to reclassify mass transit spending in coordination with the move. No longer would it be counted as part of the housing and community development function, but instead as part of function 500, “commence and transportation” – specifically subfunction 503, “ground transportation,” together with spending on highways and railroads.

Henceforth (and to this day), when one looks in the federal budget and asks how much is spent on urban and community development programs across all agencies, no mass transit dollars appear. The entirety of mass transit spending is counted in the transportation function (later split off from Commerce and renumbered as function 400).

[Continued in the fourth installment, here, which discusses how Richard Nixon tried to reverse the move – and then some – just three years later.]