April 14, 2017

April 14, 2017

The big programmatic cuts in transportation proposed in President Trump’s proposed “skinny” budget for discretionary programs can be divided into two types.

First, there are the cuts in major discretionary grant programs (TIGER grants and new mass transit systems) that the White House says are inefficient. But Budget Director Mick Mulvaney has also said that the forthcoming infrastructure plan will propose alternative programs that would fund or finance at least some of the types of projects currently served by TIGER and new starts – only on the mandatory side of the budget, not the discretionary side.

Then there are the other types of cuts – the elimination of federal subsidies for money-losing rail and airline routes. Unlike the other proposed cuts, these programs are unlikely to be funded in some alternate way in a future infrastructure package. Killing these programs would, in some ways, be the endpoint of the deregulatory process begun 40 years ago.

For most of the 20th century, the federal government regulated most aspects of railroad and airline service. The Interstate Commerce Commission told railroads how much they could charge on each route and prohibited railroads from cutting off service (freight or passenger) on existing routes without ICC permission. The Civil Aeronautics Board did the same thing with airlines, regulating fares and mandating service to selected cities.

Some routes were probably unprofitable on their own, but the goal of the regulatory system was to require higher-than-necessary fares on profitable routes in order to balance out the cost of maintaining service on unprofitable routes. In this way, the cost of subsidizing unprofitable service was borne by travelers on profitable parts of the system.

For railroads, the passenger service the ICC required them to provide grew increasing unprofitable after World War II due to competition from highways and airlines. And ICC regulations left railroads less able to compete against trucks for freight, particularly after containerization started in the 1950s. So, despite a regulatory system that was supposed to guarantee them some kind of profit each year, every railroad in the Northeast United States filed for bankruptcy between 1967 and 1973.

Faced with a series of bad options, Congress (at the behest of Transportation Secretary John Volpe) responded in 1970 by creating a new passenger rail operating company (later named Amtrak). The law creating Amtrak required DOT to designate a “basic system” of intercity passenger rail routes and directed Amtrak to begin “provision of intercity rail passenger service between points within the basic system” by May 1, 1971.

After two years, Amtrak could ask the ICC for permission to terminate routes that Amtrak determined were “not required by public convenience and necessity, or will impair the ability of the Corporation to adequately provide other services.” (See the Eno Transportation Library’s collection of documents on President Nixon’s decision to sign the Amtrak bill and the DOT-White House negotiations on the Amtrak route map.) But Amtrak had to go through the same cumbersome ICC process as the freight railroads had.

In 1980, the Staggers Act deregulated the railroad industry, so Congress then passed a law in 1981 requiring Amtrak to get permission from Congress before canceling any existing service. The enforcement mechanism was a one-house legislative veto, a type of Congressional disapproval process ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1983, so Congress amended the law in 1986 to require a 120-day review by Congress before any route discontinuation could take effect. This gave Congress time to work through the appropriations process and make sure the route stayed open.

Congress eventually repealed the statutory requirement to come to them for permission to end service in 1997. But the law still requires Amtrak to “operate a national rail passenger transportation system which ties together existing and emergent regional rail passenger service and other intermodal passenger service.” And the current statute allowing Amtrak to end service is explicitly tied into the annual appropriations process, which has kept on giving Amtrak the bare minimum amount of operating subsidy each year to operate the existing system.

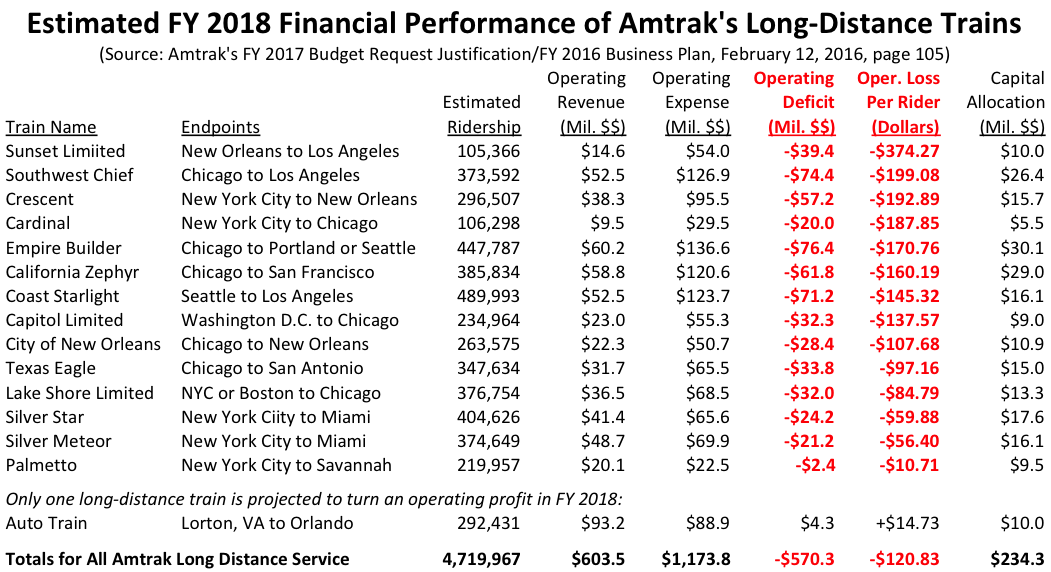

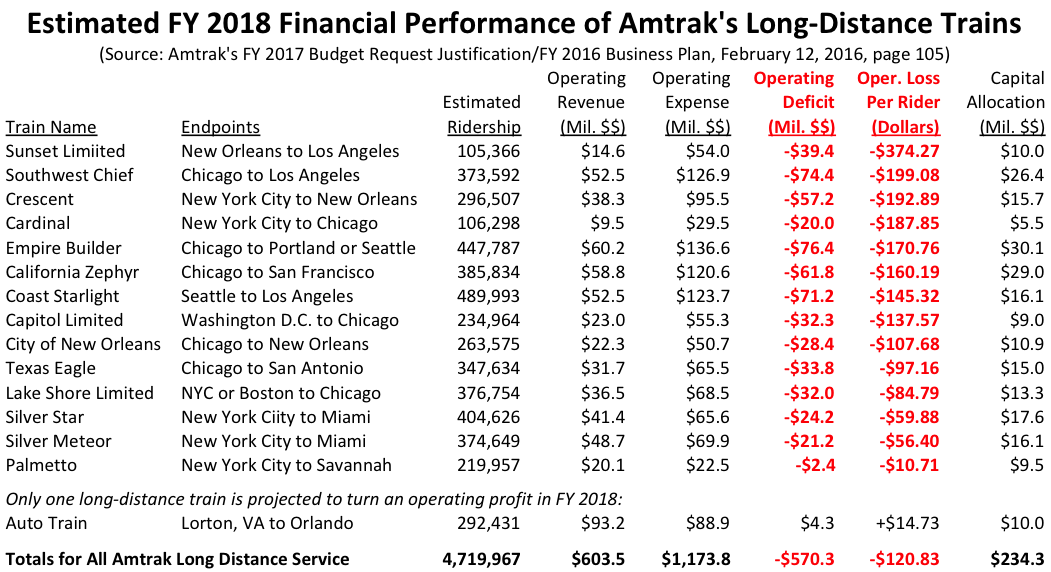

The fine print of the Trump Administration’s proposal to kill off operating subsidies for long-distance routes won’t be available until mid-May. But Amtrak’s own numbers from its FY 2017 budget justifications project that its long-distance trains will run an operating loss of $570 million in fiscal 2018 – an average of $121 per passenger. And this does not count $234 million in FY18 capital costs allocated to the long-distance service. In total, the cost of continuing the long-distance service is estimated to be $805 million in 2018.

If Congress were to stop providing operating subsidies for long-distance routes, this would not necessarily mean the end of all service. The Auto Train actually runs a small operating profit, and the Palmetto loses less than $11 per passenger – a fare increase could easily get that train to the break-even point. Silver Service, with losses of less than $60 per passenger, could potentially also be made profitable with a fare increase.

But most of the rest of the long-distance routes lose $100 per passenger per trip, or more. (Sometimes much more – the Sunset Limited loses almost $375 per passenger, not counting allocated capital costs. Documents found by ETW at the Nixon Library show that the Nixon White House actually tried to kill the Sunset Limited when Amtrak was founded but eventually acceded to DOT’s wishes to keep the route going.) The level of fare increase necessary to get to profitability would almost certainly drive down demand, necessitating even higher fares (the “death spiral”).

This situation is by no means new. GAO reported in 1995 that Amtrak’s long-distance routes only recovered about 50 cents on every dollar of their allocated costs, and then reported in 2007 that Amtrak’s long-distance routes “account for 15 percent of riders but 80 percent of financial losses.” But Congress keeps on providing the money to operate the trains, with political justifications that usually don’t discuss the end-points of the train (all of which have hub airports) – instead, Senators usually cite the small towns in between that don’t want to see their rail service go away. Amtrak doesn’t seem to have published statistics on individual station on/offs in five years, but the last stats listed towns like Arkadelphia, Arkansas, where an average of 4 people get on or off an Amtrak train each day, or Lake Charles, Louisiana (9 people per day). (And those stats only listed the 5 busiest stations in each state.)

Which brings us to essential air service. When passing the 1978 law that deregulated the airline industry, Congress recognized that the CAB had been requiring many airlines to serve small towns that were not profitable. Section 33 of that law established the Essential Air Service subsidy program, which was intended to provide a ten-year transition period for these towns. The CAB was authorized to pay subsidies to airlines to get them to maintain the service they were providing as of the date of enactment of the law (October 24, 1978). A 2015 Congressional Research Service report notes that:

At that time, there were 746 eligible communities, including 237 in Alaska and nine in Hawaii. According to a DOT estimate, fewer than 300 of these 746 communities received subsidized service under EAS at any time between 1979 and 2015.

As the 10-year expiration date approached in 1988, Congress extended EAS for another 10 years. In the Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-264), Congress removed the 10-year time limit, extending the program indefinitely.

Over the years, Congress has added a few statutory restrictions on EAS eligibility:

- A hard limit in subsidies to no more than $1,000 per passenger. 8 airports have lost service due to this cap, including 3 last year (see list here).

- A limit of the subsidy rate no more than $200 per passenger for EAS airports that are less than 210 miles from a medium or large hub airport. 39 airports have lost service over the years due to this cap (see list here).

- A ban on EAS support for airports within 70 miles of a medium or large hub airport.

- A cutoff for airports that average less than 10 enplanements per day in a fiscal year, unless it is more than 175 driving miles from the nearest hub.

EAS subsidies are fundamentally different from Amtrak subsidies in an important way. The Secretary of Transportation is authorized to waive the enforcement of several of the recent EAS program restrictions (the $200 subsidy cap and the 10 pax/day enplanement minimum) on an airport-by-airport basis, and recent Secretaries have made extensive use of this waiver authority (no doubt in response to requests by the Senators and Congressmen who represent those areas). If the Trump Administration is serious about killing EAS, Secretary Chao can take some first steps by simply stopping the waivers. In particular, DOT stopped enforcing the $200 subsidy limit eight years ago but has made noises about starting back up – see the list of airports that would be affected here.

The actual subsidy paid varies from year to year, since enplanements cannot be predicted in advance, but here are the actual FY 2016 per-passenger subsidies paid.

|

|

FY 2016 Actual |

|

|

Pass./ |

|

Subs./ |

| State |

EAS Community |

Day |

Subsidy Paid |

Pass. |

| NE |

McCook |

3.3 |

$1,616,134 |

$778 |

| PA |

Altoona |

5.9 |

$2,371,850 |

$642 |

| WV |

Beckley |

6.6 |

$2,471,805 |

$599 |

| NY |

Jamestown (NY) |

5.7 |

$2,027,122 |

$573 |

| TX |

Victoria |

6.0 |

$2,053,469 |

$546 |

| NE |

Alliance |

6.4 |

$2,117,500 |

$528 |

| CO |

Pueblo |

2.9 |

$925,980 |

$518 |

| MN |

Thief River Falls |

7.3 |

$2,176,866 |

$504 |

| KS |

Dodge City |

5.7 |

$1,686,570 |

$470 |

| AR |

Harrison |

6.9 |

$1,827,409 |

$436 |

| UT |

Moab |

16.2 |

$2,211,169 |

$432 |

| NM |

Carlsbad |

9.2 |

$2,469,663 |

$429 |

| MT |

Havre |

7.4 |

$1,965,803 |

$427 |

| PA |

Franklin/Oil City |

5.8 |

$1,547,632 |

$423 |

| PA |

DuBois |

8.7 |

$2,252,184 |

$412 |

| AZ |

Prescott |

10.0 |

$2,568,486 |

$411 |

| WV |

Parkersburg/Marietta, OH |

13.5 |

$3,420,872 |

$406 |

| KS |

Liberal/Guymon, OK |

6.6 |

$1,629,380 |

$396 |

| WV |

Greenbrier/W. Sulphur Sps |

14.4 |

$3,507,888 |

$389 |

| MS |

Tupelo |

16.2 |

$2,158,222 |

$387 |

| PA |

Lancaster |

10.6 |

$2,512,692 |

$379 |

| MI |

Ironwood/Ashland, WI |

15.5 |

$3,551,742 |

$366 |

| MT |

Glendive |

8.3 |

$1,871,294 |

$359 |

| NM |

Clovis |

14.5 |

$3,240,470 |

$356 |

| PA |

Bradford |

9.7 |

$2,082,430 |

$343 |

| NM |

Silver City/Hurley/Deming |

16.1 |

$3,412,480 |

$338 |

| UT |

Vernal |

15.0 |

$1,583,235 |

$333 |

| AR |

Hot Springs |

7.1 |

$1,377,628 |

$321 |

| MI |

Manistee/Ludington |

9.2 |

$1,844,547 |

$319 |

| TN |

Jackson |

10.3 |

$2,054,950 |

$318 |

| MT |

Glasgow |

10.3 |

$2,030,855 |

$314 |

| AZ |

Page |

11.1 |

$2,135,446 |

$308 |

| MT |

Wolf Point |

11.3 |

$2,171,235 |

$306 |

| CO |

Alamosa |

10.8 |

$2,005,395 |

$296 |

| PA |

Johnstown |

13.6 |

$2,396,358 |

$281 |

| IA |

Fort Dodge |

21.2 |

$3,724,020 |

$281 |

| NY |

Ogdensburg |

13.2 |

$2,266,928 |

$275 |

| NE |

Scottsbluff |

9.4 |

$1,564,931 |

$267 |

| NE |

Chadron |

13.1 |

$2,169,234 |

$264 |

| CO |

Cortez |

10.6 |

$1,708,769 |

$257 |

| NY |

Massena |

16.9 |

$2,698,608 |

$256 |

| WV |

Clarksburg/Fairmont |

14.4 |

$2,305,224 |

$255 |

| AL |

Muscle Shoals |

17.2 |

$1,739,712 |

$243 |

| IA |

Mason City |

24.3 |

$3,658,230 |

$241 |

| MD |

Hagerstown |

11.9 |

$1,797,260 |

$241 |

| KY |

Owensboro |

12.5 |

$1,867,985 |

$239 |

| MS |

Greenville |

14.2 |

$1,896,237 |

$239 |

| OR |

Pendleton |

11.5 |

$1,659,090 |

$238 |

| NE |

North Platte |

11.0 |

$1,632,000 |

$237 |

| KS |

Salina |

8.8 |

$762,982 |

$236 |

| ND |

Devils Lake |

22.7 |

$3,320,989 |

$234 |

| CA |

El Centro |

14.0 |

$1,311,518 |

$231 |

| AR |

Jonesboro |

14.0 |

$1,937,497 |

$221 |

| NY |

Plattsburgh |

21.5 |

$2,857,971 |

$213 |

| NE |

Kearney |

12.4 |

$1,643,804 |

$213 |

| MT |

Sidney |

26.1 |

$3,445,646 |

$211 |

| AR |

El Dorado/Camden |

10.9 |

$1,398,475 |

$211 |

| CA |

Crescent City |

28.1 |

$3,480,340 |

$198 |

| ME |

Presque Isle/Houlton |

38.9 |

$4,738,805 |

$195 |

| SD |

Watertown (SD) |

19.7 |

$304,220 |

$193 |

| NY |

Saranac Lake/Lake Placid |

15.3 |

$1,835,962 |

$192 |

| ME |

Augusta/Waterville |

15.9 |

$1,880,045 |

$189 |

| MO |

Cape Girardeau/Sikeston |

16.8 |

$1,975,944 |

$188 |

| IL |

Decatur |

24.8 |

$2,852,426 |

$184 |

| CA |

Merced |

26.0 |

$2,940,435 |

$182 |

| VA |

Staunton |

16.8 |

$1,891,380 |

$180 |

| MO |

Fort Leonard Wood |

24.5 |

$2,752,753 |

$179 |

| AZ |

Show Low |

11.4 |

$1,244,628 |

$174 |

| IA |

Burlington |

20.4 |

$2,218,424 |

$173 |

| MS |

Laurel/Hattiesburg |

37.4 |

$3,981,510 |

$170 |

| MO |

Kirksville |

15.3 |

$1,623,392 |

$169 |

| NH |

Lebanon/White River Jct. |

31.0 |

$3,104,143 |

$160 |

| WV |

Morgantown |

24.0 |

$2,342,555 |

$156 |

| KS |

Hays |

24.9 |

$2,431,497 |

$156 |

| IL |

Quincy/Hannibal, MO |

25.1 |

$2,431,286 |

$155 |

| ND |

Jamestown (ND) |

32.3 |

$3,028,225 |

$150 |

| IL |

Marion/Herrin |

28.9 |

$2,562,819 |

$141 |

| ME |

Rockland |

22.5 |

$1,967,434 |

$140 |

| VT |

Rutland |

16.4 |

$1,355,583 |

$132 |

| MI |

Iron Mountain/Kingsford |

36.1 |

$2,966,166 |

$131 |

| PR |

Mayaguez |

16.6 |

$1,288,357 |

$124 |

| ME |

Bar Harbor |

25.7 |

$1,987,057 |

$124 |

| MI |

Alpena |

28.1 |

$2,157,184 |

$122 |

| MI |

Escanaba |

49.3 |

$3,524,772 |

$114 |

| SD |

Pierre |

70.3 |

$606,636 |

$108 |

| MN |

Chisholm/Hibbing |

40.1 |

$2,671,234 |

$106 |

| UT |

Cedar City |

43.0 |

$2,610,261 |

$97 |

| MN |

International Falls |

37.7 |

$2,189,324 |

$93 |

| MS |

Meridian |

83.4 |

$4,000,698 |

$77 |

| WY |

Laramie |

46.7 |

$2,046,800 |

$70 |

| NY |

Watertown (NY) |

53.2 |

$2,314,505 |

$70 |

| MI |

Muskegon |

53.5 |

$2,054,099 |

$61 |

| WI |

Eau Claire |

58.1 |

$1,988,732 |

$55 |

| KY |

Paducah |

65.1 |

$2,084,285 |

$51 |

| MN |

Brainerd |

53.5 |

$1,697,814 |

$51 |

| WI |

Rhinelander |

68.8 |

$2,083,650 |

$48 |

| MI |

Sault Ste. Marie |

66.5 |

$1,905,822 |

$46 |

| MT |

West Yellowstone |

69.8 |

$500,764 |

$29 |

| IA |

Waterloo |

80.6 |

$1,317,334 |

$26 |

| MI |

Hancock/Houghton |

78.4 |

$1,279,498 |

$26 |

| KS |

Garden City |

83.5 |

$1,357,800 |

$26 |

| MN |

Bemidji |

76.5 |

$1,217,620 |

$25 |

| NE |

Grand Island |

84.1 |

$1,277,388 |

$24 |

| MI |

Pellston |

84.2 |

$1,225,363 |

$23 |

| WY |

Cody |

78.4 |

$1,085,268 |

$22 |

| SD |

Aberdeen |

84.3 |

$1,054,369 |

$20 |

| MT |

Butte |

80.8 |

$867,213 |

$17 |

| MO |

Joplin |

91.2 |

$516,880 |

$9 |

April 14, 2017

April 14, 2017