February 22, 2019

Next week will mark the 100th anniversary of the first gasoline tax in the United States as a motor fuel – enacted by the state of Oregon on February 25, 1919. ETW will have a story about the Oregon experience on that date, but today we have a “prequel,” as it were – an overview of the attempts to tax gasoline in the U.S. before Oregon made the initial leap in 1919.

The Civil War.

It is not generally remembered today – and this author would certainly have never figured it out if the entire 1789-present database of the U.S. Statutes at Large and Congressional Serial Set had not been put online with word search capability – but the federal government actually enacted an excise tax on gasoline all the way back in 1864.

The needs of the Civil War prompted not only the first-ever federal income tax (ruled unconstitutional after the fact), but also a series of wartime excise taxes on every conceivable item that a person might purchase. Included in these excises were levies on anything that might be burned to provide illumination in a lamp. That section of the revenue bill approved by the House (H.R. 504, 38th Congress) taxed many other sources of lamp fuel while never mentioning gasoline.

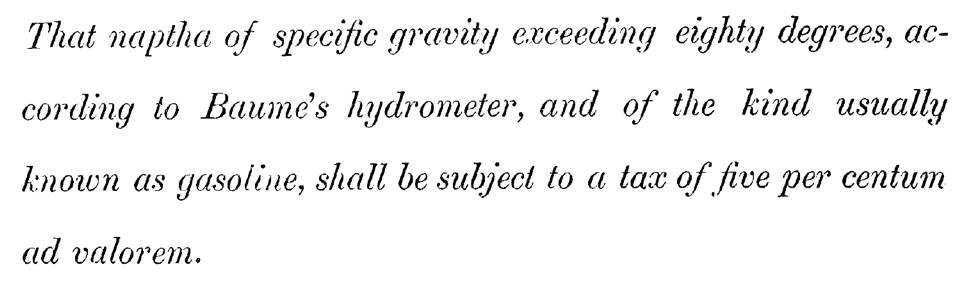

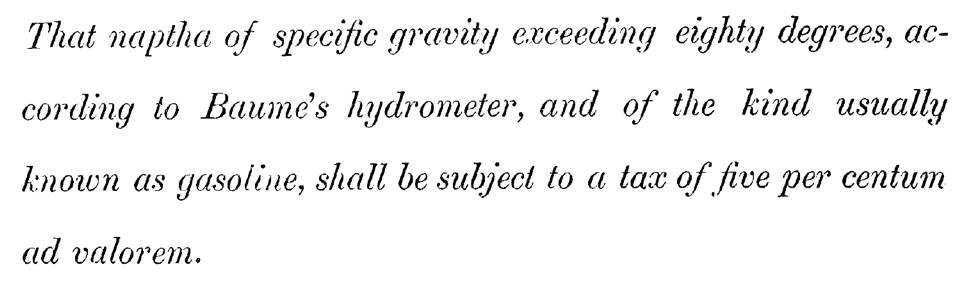

But the Senate Finance Committee, when filing its report on H.R. 504 on May 19, 1864, added an amendment to the section relating to lamp fuels providing, also:

This committee amendment was adopted on the Senate floor without debate by voice vote and was accepted by the House. The illumination fuel provision became section 94 of the Revenue Act of 1864 (13 Stat. 223). But those excise taxes were allowed to expire after the end of the war, having gained only de minimis revenue from gasoline, and nothing much else was ever said about gasoline as lamp fuel.

The advent of the automobile.

In the mid-1880s, several different German engineers figured out how to use four-stroke internal combustion engines, fueled by gasoline, to move horseless carriages. Across the Atlantic, several companies were created to manufacture automobiles in the early 1890s, and the industry grew rapidly. Although steam and electricity were initially more popular in the U.S., by 1902, the gasoline-powered Oldsmobile had become the most popular car in America, selling 2,750 units.

Sales of new cars grew rapidly in each year of the new century, but they really went into overdrive once Henry Ford got his assembly line going in 1906, making massive numbers of cars that could be afforded by the middle class.

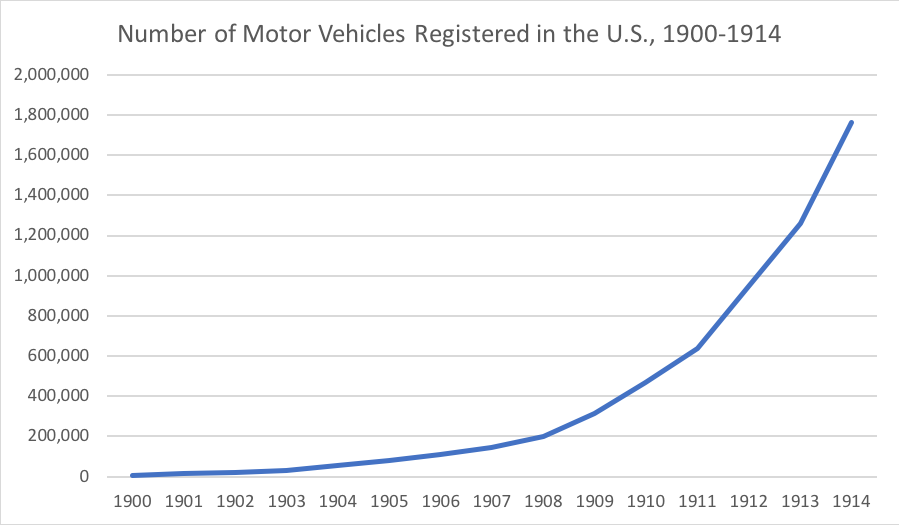

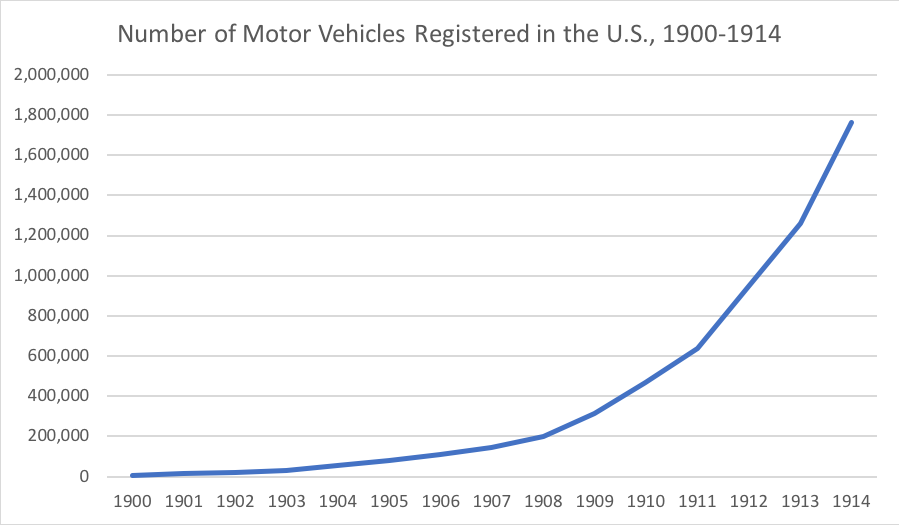

There are no official records of the number of automobiles manufactured or sold in the U.S. in those days, but starting in 1901, New York became the first state to require owners of automobiles to register them with the state. According to a table put together later by the Federal Highway Administration, all states had enacted some form of registration by 1913, and while most states started out their registration schemes as a one-time requirement, eventually they switched to annual re-registrations as a revenue source.

The growth curve in the number of motor vehicles registered in the United States during those years is astounding.

That level of growth in the number of cars on the road – almost all of them gasoline-powered after about 1910 – naturally led to an equivalent rise in the gasoline sales industry and infrastructure.

Buildup to World War I.

The first known proposal in the United States to levy any kind of taxation on motor fuels arose at the start of World War I. The Sixteenth Amendment (allowing income taxation) had just been ratified in February 1913, and though a new federal income tax had been levied on top earners effective in March 1913, the peacetime U.S. norm of financing the government primarily through a tariff on imports and on the pastimes of the nation’s drinkers and smokers remained in effect. In the fiscal year ending on June 30, 1914, the tariff and the “sin taxes” on alcohol and tobacco combined for 82.5 percent of total federal revenues.

| Total Federal Revenues, FY 1914 |

|

Million $ |

Pct. |

| Customs Duties |

292.3 |

39.8% |

| Alcohol Taxes |

226.2 |

30.8% |

| Tobacco Taxes |

80.0 |

10.9% |

| Income Taxes |

71.4 |

9.7% |

| Non-Tax Revenues |

64.8 |

8.8% |

| Total Revenues |

734.7 |

100.0% |

| Source: Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, fiscal year ending June 30, 1914 |

Two days before the end of fiscal year 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire was assassinated, and over the July-September period what became World War I painstakingly began. It became obvious to the Wilson Administration that a full-out war in Europe would probably make a significant dent in the willingness and ability of European nations to export goods across the Atlantic to the United States, which would mean a significant drop in customs revenue. In those days, balanced budgets (or budgets close to balance) were also a peacetime norm, which meant new revenues would be needed.

On September 4, 1914, President Wilson appeared before a joint session of Congress to “respectfully urge that an additional revenue of $100,000,000 be raised through internal taxes devised in your wisdom to meet the emergency. The only suggestion I take the liberty of making is that such sources of revenue be chosen as will begin to yield at once and yield with a certain and constant flow.”[1]

A bill was quickly introduced in the House (H.R. 18891, 63rd Congress) and was reported by the Ways and Means Committee with almost no changes on September 22, 1914. The Ways and Means report explained that since the new income tax system did not withhold income, but instead relied on taxpayers to send in their yearly tax in June of each year, increasing the rates would not meet Wilson’s immediacy requirement. The committee said that they had “endeavored to propose taxes that can be collected by the present force of internal revenue officials, slightly increased in number, with a small additional expense, and with a minimum disturbance of trade.”[2]

When the bill went to the House floor on September 24, 1914, Ways and Means chairman Oscar Underwood (D-AL) told the House that the taxes in this war revenue bill were the same as in the revenue bill for the last war (the Spanish-American War), with one exception: “The only tax in this bill that you did not father in 1898 is a tax on gasoline, and this bill levies a tax on gasoline of 2 cents a gallon.”

The bill proposed to raise $105 million in additional revenues, as follows: $32.5 million in higher beer taxes, $6 million in higher wine taxes, $30 million in new stamp taxes, $5 million in higher tobacco taxes, $1.5 million from a new tax on telephone and telegraph messages, $10 million from a variety of new taxes on operators of unpopular businesses (bankers, stock brokers, pawnbrokers, and the proprietors of theaters, museums, concert halls, circuses, bowling alleys and billiard rooms) – and an unprecedented $20 million to be raised from a new two cent per gallon federal excise tax on “gasoline, motor spirits, naphtha, and other products obtained from crude, partially refined, or residuum oils, and suitable for motor power”.[3]

Obviously, the authors of the tax bill assumed one billion taxable gallons sold per year, against a total U.S. population of roughly 100 million people in 1914, with only 1.7 million registered automobiles in the country. And the earliest owners of automobiles tended to be the kinds of people who today own single-piston-engine airplanes or small sailboats – in other words, fairly well-off white males with a bit of an adventurous spirit.) During the brief discussion of the proposed gasoline tax during House debate on the bill, there was a dispute between chairman Underwood and a member from Pennsylvania (which was then a major oil producing state) as whether or not a significant amount of gasoline was made from natural gas, not crude oil, and thus would not be taxed.[4] It is important to note that the taxes raised by the bill were all selected so that none of them could be characterized as a tax on a “necessity.”

To the brief extent that the gasoline tax itself was debated in the House in 1914, it was as part of the overall partisan take on the bill (Republicans favored an increase in tariff rates instead of a tax hike). During debate, Rep. Ben Johnson (D-KY) said “…import duties will fall off $125,000,000 in the next year. The Republicans prefer to levy this $125,000,000 on the necessaries of life. By this bill it is proposed to collect $105,000,000 of that amount without putting a single dollar of it upon the necessaries of life. Which do you prefer? The Democrats prefer to tax the gasoline which goes into the automobile. We prefer that kind of a tax rather than to tax the necessaries of life.”6 The House passed the bill without amendment by a vote of 234 to 135.

In the Senate, the Finance Committee took a different view of the gas tax. By October 2, rural interests had convinced the internal Democratic caucus of the Finance membership to cut the gas tax in half and replace the lost revenue with a horsepower-based sales tax on automobiles (50 cents per horsepower).[5] (Horsepower was actually a pretty good metric for one of the primary social costs of automobile use – the dust thrown up by driving on dirt roads – and was taxed in Great Britain and as part of the registration fee in several U.S. states.) But further internal debate at Finance convinced the panel to kill the gas tax altogether and also not to tax vehicles.

The committee’s report said “Your committee recommend that this provision of the House bill be eliminated altogether.”[6] To replace the $20 million per year lost by eliminating the gas tax, the Senate bill added another $10 million to the beer tax and added $5 million in taxes on whiskey and other spirits, while also adding taxes on other luxuries (raising $4 million from a new tax on perfumed cosmetics and $3 million from a new tax on chewing gum).[7] On October 13, the Senate agreed to the Finance Committee’s amendment striking the proposed gasoline tax by voice vote without debate.[8] The Senate later passed the amended bill by a 34 to 22 vote.

A House-Senate conference committee was appointed and made its report on October 22, recommending that the House agree to the Senate’s elimination of the gasoline tax. The chairman of the Senate Finance Committee said “A large part of the time of the conference was taken up in the discussion of that subject and in the discussion of a tax upon rectified spirits and increasing the tax over the House rate upon beer. As I have stated, the result of that controversy was that gasoline was left out of the bill, the tax rate on rectified spirits was left out of the bill, and the House rate upon beer was adopted.”[9] (In other words, the House agreed to give up its new gas tax in exchange for the Senate giving up its position on the beer tax rate and new whiskey tax.) The conference report, containing no gas tax, passed the House 126 to 52 and passed the Senate 35 to 11 and was signed into law by President Wilson.

A little over a year later, in December 1915, Wilson’s Treasury Secretary, William McAdoo (a fascinating man – as a former railroad executive, he had built what are now the PATH tunnels under the Hudson River and later ran the entire U.S. railroad industry once Wilson nationalized it during the war, and he was also Wilson’s son-in-law) submitted his annual report to Congress for fiscal year 1915. It contained recommendations for the Wilson Administration’s budget program.

The report said that “…we now have to consider the new forms of taxation which must be resorted to for the purpose of providing the additional revenues required, the major part of which is needed to carry out the enlarged program for national defense. The total amount so required for the year 1917 is $112,806,394.22”.[10] In addition to recommending increases in the new income tax, the report also closed by saying that “A tax could also be imposed on such products as gasoline, crude and refined oils, horsepower of automobiles and other internal combustion engines, and various other things, where collection could be made at the source with certainty and with small expense.”[11]

Wilson himself told a joint session of Congress on December 7, 1915 that “there are many additional sources of revenue which can justly be resorted to without hampering the industries of the country or putting any too great charge upon individual expenditure. A tax of one cent per gallon on gasoline and naphtha would yield, at the present estimated production, $10,000,000; a tax of fifty cents per horse power on automobiles and internal explosion engines, $15,000,000…”

The Wilson 1915 gas tax proposal got no traction in Congress. Carl-Henry Geschwind, in A Comparative History of Motor Fuels Taxation, 1909-2009 (Lexington Books, 2017), found archival evidence that “Claude Kitchen, the radical agrarian from North Carolina who chaired the Ways and Means Committee, removed the gasoline tax from consideration after receiving a protest from his state’s Farmer’s Alliance.[12]

U.S. entry into World War I.

On April 6, 1917, at President Wilson’s urging, the United States declared war on Germany and formally entered World War I. Congress had to raise revenues quickly, and the main vehicle for that was a drastic increase in the new income taxes – the War Revenue Act of 1917 increased the top income rate from 15 percent to 67 percent. But while McAdoo had again suggested that a new gasoline tax be part of the war revenue mix, the Ways and Means Committee’s bill (H.R. 4280, 65th Congress) did not tax gasoline, nor did the Senate contemplate adding a gas tax to the bill.

Another war revenue measure was needed the following year. McAdoo tried, one last time, to get a gasoline tax from Congress, suggesting a level of 2 cents per gallon. During its hearings on the proposal in July and August, discussions of potential gas shortages were more extensive than the discussions of the funds that could be raised. But this time, the Ways and Means bill (H.R. 12863, 65th Congress) reported in early September 1918 contained, in section 902, a 2 cent per gallon gasoline tax, estimated to raise $40 million in the first year.

That bill passed the House on September 20, 1918. The Senate Finance Committee promptly began to hold hearings in September and October, during which opposition to the tax was heard from the taxicab and dry cleaning industries. During the October hearings, the head of the oil division of the U.S. Fuel Administration, William Requa, testified that gasoline was no longer, as chairman Underwood had claimed four years earlier, a luxury good:

The CHAIRMAN. Your position is that we should not impose a tax on gasoline because it is a necessity?

Mr. REQUA. I have no views as to whether you should tax a necessity but I say that if it is taxed it would be taxing a necessity.

The CHAIRMAN. In other words, you think if we do not propose to tax necessities, then we ought not to tax gasoline?

Mr. REQUA. You could tax coal with the same justification.

Before the Finance Committee could complete its work on the bill, an armistice in the war was declared on November 11, 1918. This had the effect of significantly lowering the amount of money that the bill needed to raise, so the version of H.R. 12863 reported from Finance on December 6, 1918 struck the House’s 2 cent gas tax, and the eventual House-Senate conference committee once again agreed with the Senate’s action.

It is important to note that none of these discussions of a federal gasoline tax in 1914-1918 had anything to do with federal spending on roads. All such discussions were about raising money for general revenues. Linking a tax on gasoline consumption to public spending on roads would have to wait until 1919, in Oregon.

[1] Additional Revenue – Address of the President of the United States, September 4, 1914 as printed in House Document No. 1157, 63rd Congress, 2nd Session.

[2] U.S. Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Ways and Means. Report to accompany H.R. 18891 (House Report No. 1163, 63rd Congress, 2nd Session). September 22, 1914 p. 6.

[3] 51 Congressional Record p. 15654 (September 24, 1914).

[4] 51 Cong. Rec. pp. 15654-15655 (September 24, 1914).

[5] “Reduced Gasoline Tax Is Agreed On,” Oregonian, October 3, 1914 p. 5.

[6] U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Finance. Report to accompany H.R. 18891 (Senate Report No. 813, 63rd Congress, 2nd Session) October 8, 1914 p. 2.

[7] U.S. Congress. Senate. War Revenue Bill: Comparison of Additional Revenues. (Senate Document No. 596, 63rd Congress, 2nd Session). 1914.

[8] 51 Cong. Rec. p. 16535 (October 13, 1914).

[9] 51 Cong. Rec. p. 16909 (October 22, 1914).

[10] U.S. Department of the Treasury. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of Finances for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1915 (printed as House Document No. 359, 64th Congress, 1st Session) p. 51.

[11] Treasury Annual Report..1915 p. 52.

[12] Geschwind, Carl-Henry. A Comparative History of Motor Fuels Taxation, 1909-2009. (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017) p. 25.