When we ask, “what does the federal government spend on transportation,” the answer isn’t always just about the Department of Transportation. The federal budget also breaks down spending across agencies into 17 “functional categories” based on the function of government that each individual budget account is primarily serving. One of those functions is also “Transportation.” (Function number 400, FYI.)

The transportation budget function includes:

- Everything at USDOT except for three Maritime Administration accounts (Maritime Security Program, Cable Security Fleet Program, and Tanker Security Fleet Program) that are classified as national defense.

- The Transportation Security Administration.

- The U.S. Coast Guard (except that a certain share of Coast Guard operating expenses is classified by law as national defense in each annual appropriations act).

- The “Aeronautics” budget account at NASA.

- The transportation-related independent commissions and advisors (FMC, STB, NTSB, and the Amtrak Inspector General).

- In the past, the 9/11 and COVID aid programs for aviation that were assigned to the Treasury Department to administer.

This analysis focuses on budget authority, which are the decisions made by Congress to enact laws allowing a certain amount of spending commitments to be made. (The other way to look at spending is outlays, which represents the cash going out the Treasury doors to pay off the commitments made pursuant to budget authority, but since Congress can’t easily control the rate at which the outlays happen, from a Congressional decision-making point of view it is better to focus on budget authority).

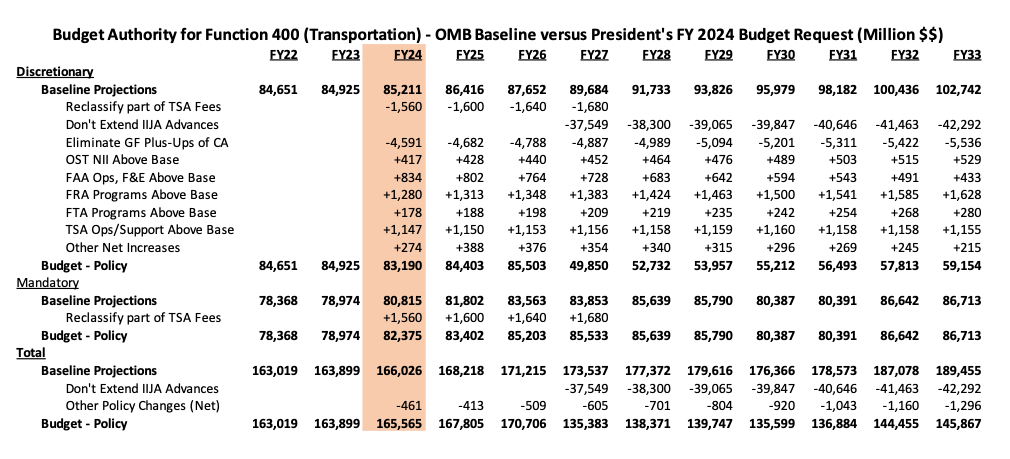

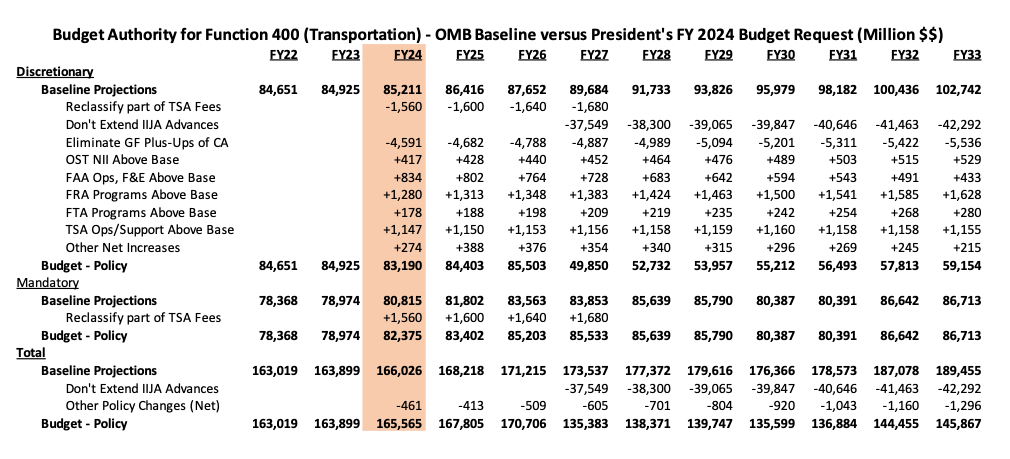

The Office of Management and Budget’s new “baseline” predictions for fiscal 2024 (baseline is whatever is already on the books, plus a repeat of everything else that was done in the previous year) is for $166 billion in total transportation budget authority in 2024, and extrapolating this forward, they get $1.767 trillion over ten years.

(This baseline is already a bit tweaked from what is required by law – OMB is removing the forward-extrapolation of emergency funding provided in 2023 and 2023 only, like the $1.2 billion in emergency appropriations for FHWA, FTA, and the Coast Guard. This lowers spending by $13.2 billion, extrapolated, over a decade.)

The baseline divides transportation spending into two types: discretionary (provided by the Appropriations Committees and not mandated by any other law), and mandatory (provided by authorizing committees, or in a budget reconciliation bill, or by the Appropriations Committees if they are required by law to provide it for some kind of entitlement benefit).

On the mandatory side, the baseline calls for $80.8 billion in budget authority in 2024 and $836 billion over a decade. Most of that is Highway Trust Fund contract authority (provided by the IIJA through 2026 and extrapolated at a flat-line level thereafter), plus $3.35 billion per year extrapolated contract authority from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (which expired in 2023 and is extrapolated flat-line for the full decade), or Coast Guard retired pay (the only mandatory account in transportation that is required to be carried by the Appropriations Committees).

The Administration only proposes one change this year on the mandatory side of the transportation function – reclassifying part of the TSA’s Aviation Security Fee. Section 601 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (a.k.a. “Ryan-Murray I”) increased the per-passenger fee and then dedicated all of the projected increase, through fiscal year 2023, to deficit reduction by classifying it as a mandatory offsetting receipt. The rest of the fees remained classified as a discretionary offsetting collection so it offsets new TSA appropriations dollar-for-dollar as the money comes in.

The Ryan-Murray law did this as one of the “pay-fors” to offset an increase in the overall discretionary appropriations caps. The diversion of the excess fees to deficit reduction was extended to FY 2024 and 2025 by section 3001 of the July 2015 Highway Trust Fund extension as one of the pay-fors for that law’s $8 billion Trust Fund bailout. And they were extended one more time, by section 30202 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, for 2026 and 2027 as another pay-for for an appropriations cap increase.

The budget proposes to reclassify the last four years of the mandatory side of the fee (FY 2024-2027) as discretionary, which would make the net mandatory side of the budget $6.5 billion larger over four years and make the net discretionary side $6.5 billion smaller.

Congress is unlikely to agree to this, because that $6.5 billion was already used as a pay-for for new spending that has already been made. To agree to the transfer would allow the same fees to be used as a pay-for a second time for a new round of appropriations.

Other than that, the budget proposes no changes on the mandatory side of transportation funding.

On the discretionary side, by law, each account gets an annual inflation increase in the baseline (there is one rate for salaries and a second rate for everything else), and the law requires scorekeepers to assume that any appropriations that were made last year will be made every year in the future, plus inflation, so the baseline extends and bumps up all advance appropriations made by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) after they expire in 2026.

The budget proposal makes clear that it is the Administration’s position not to extend the IIJA’s advance appropriations past their expiration in 2026. So, starting in 2027, the budget reduces transportation discretionary funding by $37.5 billion to get rid of the extrapolated and inflation-increased continuation of the IIJA advances. The budget reduces total spending by $279 billion over seven years in this fashion.

The budget then proposes to get rid of the annual “plus-up” appropriations that started being made in fiscal year 2018 for the highway, mass transit, and airport contract authority programs (after the February 2018 budget deal with President Trump opened the spending floodgates and ended the attempt at austerity made in the 2011 debt crisis). Those three accounts total $4.6 billion in the baseline and include almost all earmarks made by Congress, which is big reason why Congress is likely to ignore much of this proposal.

Then the budget proposes a few other changes from baseline:

- Substituting a $1.22 billion MEGA grant appropriation for the $800 million RAISE grant appropriation made last year (both grants are, technically, the same budget account – National Infrastructure Investments).

- Increasing Federal Aviation Administration programs by $834 million above baseline in FY 2024 (mostly for salary increases and for new controller hires, though FAA facilities get a good boost as well).

- Increasing Federal Railroad Administration programs by a collective $1.3 billion above baseline in FY 2024.

- Increasing Capital Investment Grants and Transit Research by, collectively,$178 million over baseline in 2024.

- Increasing Transportation Security Administration funding by $1.15 billion over baseline, mostly on salaries for new hires (the budget wants an increase in 1.412 FTEs over the FY 2023 level).

- Miscellaneous other increases that total to $274 million over baseline in 2024.

The table showing the total spending in budget 400 in the budget request is below.