In last week’s part 2 of this series, the Highway Trust Fund was facing insolvency in fiscal 1960, President Eisenhower requested a 1.5 cent per gallon increase in gasoline and diesel excise taxes to last from fiscal 1960-1973 (enough to cover the baseline shortfall and cover an estimated $10 billion Interstate cost overrun), Democratic leaders rejected the gas tax, Congress took no action, and the Eisenhower Administration, in early July 1959, threatened state governments that not only would there be zero new Interstate contract authority apportioned that year (per the statutory “Byrd Test” for Trust Fund solvency), but that they were going to force a moratorium on all highway contracts from mid-1959 through spring of 1960 and also stop reimbursing states on time for highway costs the states had already incurred.

(In the 1958 midterm elections, when Republicans took such a beating, one of the members who lost their seat was six-term incumbent Rep. John J. Allen, Jr. from Oakland, California (the last Republican to represent Oakland and the rest of Alameda County in the House of Representatives). President Eisenhower immediately named Allen Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation in January 1959. As someone who had been a Member of Congress until January 3, Allen naturally wound up doing a lot of Congressional outreach on Commerce issues in 1959, and his files at the National Archives reveal a lot about how the Eisenhower Administration interacted with Congress on Interstate highway financing.)

Ways and Means starts discussions

After months of delay, Ways and Means chairman Wilbur Mills (D-AR) decided to get serious about the Interstate funding problem at the end of June 1959. Then (as now), Congressional committees did not have the resources to do program-specific spending and revenue models for programs or trust funds, and relied on the executive branch to provide “technical assistance.”

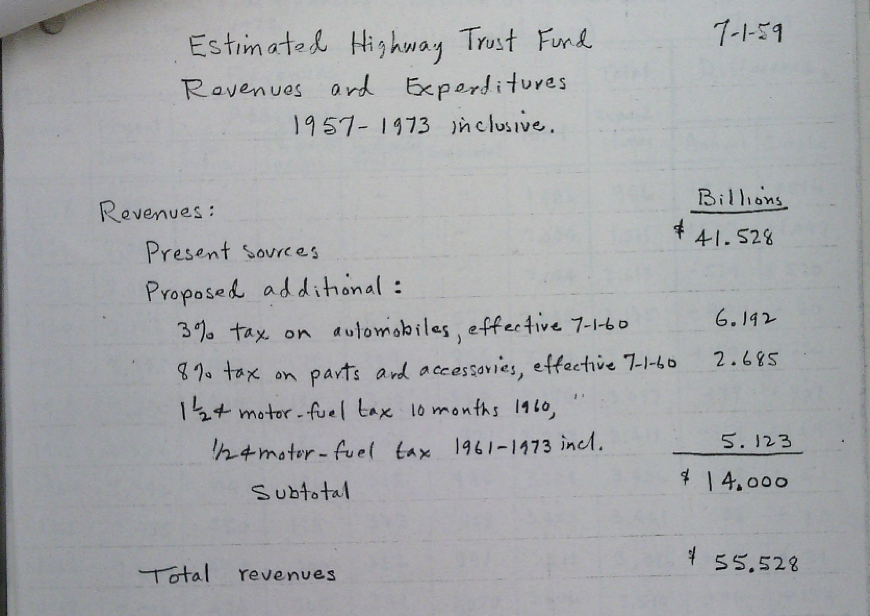

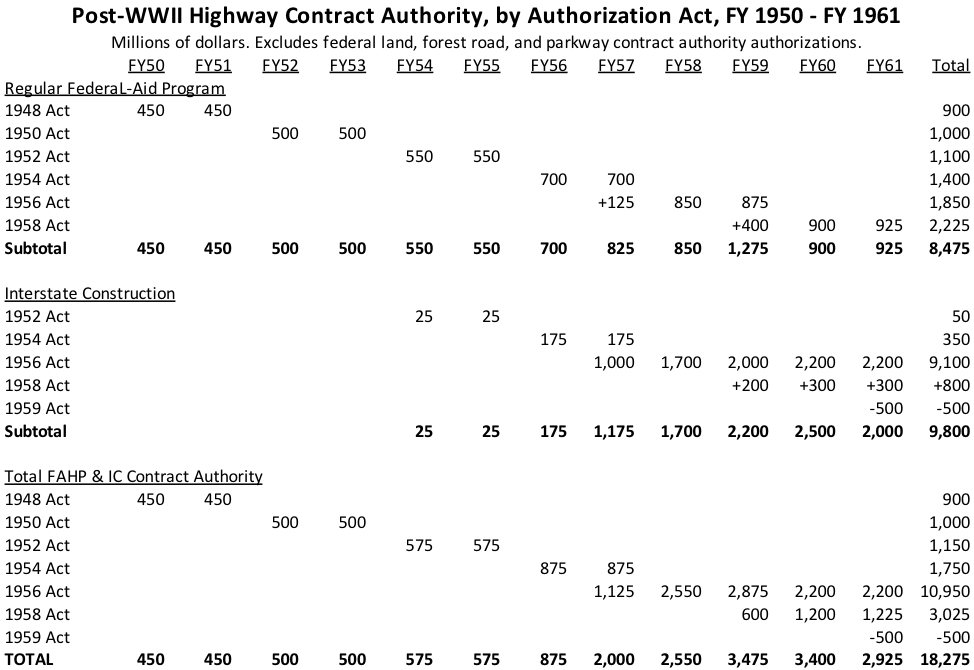

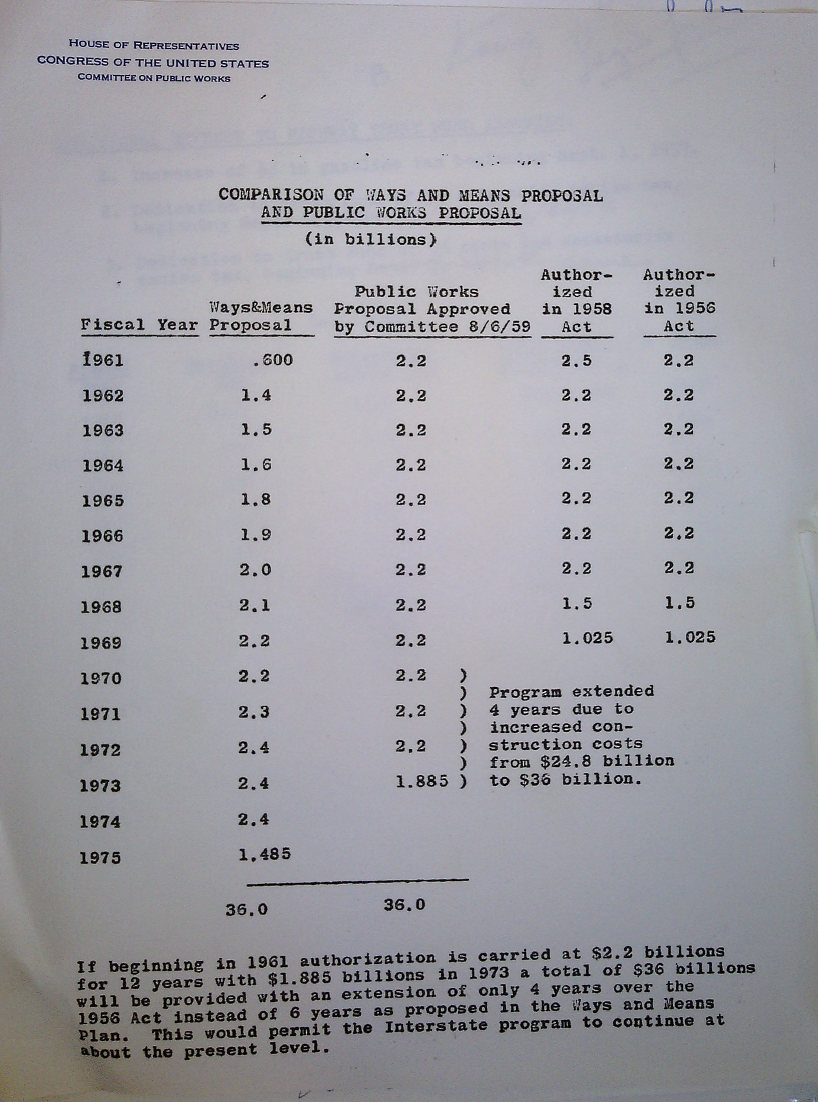

Around June 30, Ways and Means asked the Bureau of Public Roads for a cash flow analysis of a scenario where President Eisenhower would get his 1½ cent per gallon gas tax increase – but only for the 10-month period from September 1, 1959 through June 30, 1960 – and then the tax increase would be lowered to just ½ cent per gallon after that. In combination with transfer of 3 points of the existing automobile tax and all 8 points of the existing parts and accessories tax, this would have raised an estimated $14 billion in additional revenues over the life of the Highway Trust Fund, enough to pay for the bills of the past and the latest increased Interstate cost estimates.[1] (Back in those pre-spreadsheet days, agencies sent technical assistance to the Hill in handwritten form):

Ways and Means also asked for numbers for a different scenario – a ½ cent gas tax for the final 10 months of FY 1960, plus 5 percentage points of the automobile tax and all of the tax on auto parts, both beginning in FY 1961.

Allen dictated a file memo on July 2 stating that he had just had a conversation with the new Acting Secretary of Commerce, Frederick “Fritz” Mueller, that day. (Lewis Strauss had ceased to be Acting Secretary in late June because the Senate actually voted down his nomination for the permanent job on June 19 by vote of 46 yeas, 49 nays.) Per the memo, Mueller and Allen “were thinking of the possibility of a two-year waiver of the Byrd Amendment, a two-year amendment that would fix the apportionments at $1.5 billion (instead of the statutory $2.5 billion in FY 1961 and $2.2 billion in FY 1962] and a two-year additional tax of 1½¢ as a possibility of taking us (through or) to ’61.”[2]

On July 6, Allen dictated a memo for his files about a conversation he had just had with Rep. John Byrnes (R-WI), chairman of the House Republican Policy Committee and a senior Ways and Means member who had a tight relationship with chairman Mills, and Richard Simpson (R-PA), the senior Republican on Ways and Means:

I talked with Dick Simpson and John Byrnes. Dick is not as concerned over the welfare of the contractors or the State Highway Commissions or that the work should continue at an even level as I would be. Johnny Byrnes is somewhat anxious to keep the work at a decent level without peaks and valleys, but he wants to keep the costs down. Both are in agreement, and Johnny very strongly, that there is no use talking about 1½¢ tax.

I said I would get a chart of the results based upon a ¾¢ tax effective August 1 for 3 years with no suspension of the Byrd amendment. I proposed that I would also get one for 1¢ additional for 3 years.[3]

The following day, President Eisenhower had his regular meeting with Republican Congressional leaders at the White House. The minutes of the meeting say that John Byrnes had the following exchange with Budget Director Stans and the President:

Rep. Byrnes said that Wilbur Mills is against a 1½¢ gasoline tax increase but might take a smaller amount, that hearings are starting, that the President has recommended a program and now it’s up to the majority party in Congress.

Mr. Stans noted two compromises under discussion: 1½ ¢ for two years and cut the program from 2½ billion to 1½ billion a year, or 1¢ for two years and waive the Byrd amendment. He said it would be possible, by marshaling resources, to get by, and then the new administration could deal with it again.

Rep. Byrnes felt the trouble to be that no real public interest in this situation had been aroused. The President said it would be if the program slows down. He affirmed his recommendation for a 1½¢ increase in the gas tax, but said he would accept a compromise if a satisfactory one could be worked out.[4]

On July 10, chairman Mills announced that Ways and Means would begin holding hearings on the highway revenue problems later in the month. Meanwhile, the Administration’s threats to cut off not only new contract authority apportionments (which had been known for six months) but also to force a moratorium on all new contracts and to make states wait weeks or months for reimbursements (which were new), had been transmitted to states through AASHO when they forwarded Federal Highway Administrator Bert Tallamy’s letter of July 13 to the states on July 15. The announcement landed with a bang. “State highway officials received a Federal warning yesterday that the flow of construction aid may be choked off completely this fall for several months and then be resumed only in a trickle,” stated a typical article in the Baltimore Sun on July 16.[5]

Mills held three days of hearings over July 22-24, 1959 (printed transcript here). 60 years removed, what is remarkable about the hearings is how so many highway stakeholders were against not just Eisenhower’s proposed 1½ cent gas tax increase, but were opposed to balancing the Trust Fund’s revenues and spending with any kind of additional highway user tax. We have posted a list of representative stakeholder quotes in a separate document here, but suffice it to say that the American Trucking Associations, the American Automobile Association, the motor bus operators, the cities, the counties, the farmers, the rural letter carriers, the auto manufacturers, and the AFL-CIO were all against the gasoline tax and instead supported either more borrowing, or diversion of general fund taxes, or both.

AASHO was not allowed to endorse a specific position, and the American Road Builders Association only endorsed any generic action to assure the continuation of the program at the planned rate.

The only major stakeholders to specifically endorse the motor fuel tax increase were the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Associated General Contractors and (just because they were always on the opposite side of what the truckers wanted), the Association of American Railroads.

The Commerce Department, the Bureau of Public Roads, and the Bureau of the Budget all testified at the hearings. Allen was the first witness and quoted the President’s recent statements that either Byrd Test suspension or diversion of general fund taxes would be unacceptable, and added that issuing new HTF revenue bonds would also be unacceptable to the Administration as a violation of the pay-as-you-go principle. He urged Congress to defer action on long-term Interstate financing issues until after the cost allocation study and revised cost estimate were submitted to Congress in January 1961.[6]

It was left to Tallamy, the second witness, to deliver the really bad news:

Inaction by the Congress at this session regarding the temporary increasing of trust fund revenue would result in the following:

- A 9-month stoppage of all contracting for new highway construction and right-of-way acquisition;

- The delayed payment of many vouchers submitted by the States for the reimbursement of money already expended by them for outstanding contracts; and

- Nearly cut in two the total Interstate Highway construction authorized for fiscal years 1960 through 1963.

The recommended temporary motor fuel tax increase would for all practical purposes solve all of those problems.[7]

Most of the questions went to Tallamy. Hale Boggs (D-LA), a key contributor to the 1956 Act, got Tallamy to disagree with the Administration and to say that the issuance of HTF revenue bonds would be “better than nothing.”[8] John Byrnes, the Administration’s ally, got Tallamy to elaborate on the gloom-and-doom end of the scenario where the federal government would be unable to repay states for some time for their 10 percent shares of Interstate projects or their 50 percent shares of regular federal-aid projects.

After a long-ranging discussion over many hours, Mills asked Allen “whether there is no possibility in the opinion of the administration that this problem can be resolved except through the enactment of a gasoline tax increase.” Allen responded that he was certain that the Administration opposed borrowing, diversion of general revenues, or abandonment of the pay-as-you—go principle, but he did not know “what the administration’s position would be if the Congress should decide upon other sources of [new] revenue.”[9]

Mills then said “Mr. Baker, as I understand, has introduced a bill proposing an increase in the gasoline tax for a limited period of time. It is entirely possible that this committee could include some additional increase for some limited period, but I doubt that the committee would agree to do that at all under any circumstances if the administration is to take the position that nothing additional can be taken from the general fund for the benefit of the highway trust fund…I will not support – and I have said repeatedly that I would not support – the President’s request for a cent-and-a-half increase in the gasoline tax.”[10]

Budget Director Stans testified the following day. He emphasized that fixing the HTF problem with real new revenues – not borrowing from the general fund, and not diverting general revenues – was essential to keeping the entire federal budget in balance. He said “shifting our money from pocket to pocket will not pay our bills.”[11]

Dozens of House members testified, almost all of them opposed to a gas tax increase.

Ways and Means marks up

On the Monday after the hearings concluded, July 27, a series of conversations took place in anticipation of a Ways and Means markup to begin later in the week. Allen wrote that he had talked to Wilbur Mills, who “suggested that I get the Republican members lined up on some proposition. I talked to Johnny Byrnes about this later. He thought that there was no purpose to be served by getting the Republican members together, but that there might be one if we had a proposal which the Administration was giving some assent…Such a proposal as the 1¢ for 3 years a cutback to 1.8 billion on apportionments and a leveling off at 1.6 on expenditures might have some appeal to them, and possibly as many as 5 Republican votes could be lined up one way.”[12]

A few hours later, Commerce Secretary Mueller told Allen that he had just talked to Budget Director Stans, who had just spoken with Wilbur Mills and with Treasury Secretary Bob Anderson, and that “an arrangement under which there would be a 1¢ tax for two years, a 1.6 billion apportionment in ’61 and ’62, and a suspension of the Byrd amendment during those two years might be favorably considered by the Administration.” Mueller told Allen to brief Ways and Means Republicans, and Allen wrote that ranking member Dick Simpson “indicated his disapproval” and that Jimmy Byrnes “suggested that an agreement to the suspension of the Byrd amendment would indicate we would be looking to the general fund for the revenues needed, and that the Committee might just as well transfer a sufficient portion of those revenues to the trust fund now.”[13]

The following day, Ways and Means started voting on ideas for financing the Trust Fund. In 1959, the panel worked very differently than it did today – they often did not mark up draft legislation, instead preferring to talk in broad concepts and have staff flesh them out into legislative language after the markup is over (like the Senate Finance Committee still does). And at this time, Mills did not come in with a chairman’s mark to be made the subject of the markup – instead he just let members offer different plans until one of them got enough votes to pass. (Plus, the panel was much smaller then – just 25 members, 15 Democrats and 10 Republicans, and 7 of those Democrats, including Mills, were Southern Democrats who sometimes voted more conservatively than non-Southern Democrats.)

Republicans tried their proposals first.

- Baker (R-TN) ½ cent increase in the fuels tax for three fiscal years (1960-1962) with no suspension of the Byrd test and with Interstate funding cut back as necessary – failed, 5 yeas to 20 nays.

- Byrnes (R-WI) 1 cent increase for the fiscal years 1960 and 1961, suspension of the Byrd test for FY 1962 and 1963, and Interstate funding cut back as necessary for FY 1960 and 1961 – failed, 5 yeas to 20 nays.

- Baker (R-TN) 1 cent increase for FY 1960, reduced to a ½ cent increase for FY 1961 and 1962, plus transfer of half of the existing automobile excise tax to the Trust Fund – failed, 6 yeas to 19 nays.

Then, Rep. Burr Harrison (D-VA) offered a curve ball: “No obligation shall be incurred by the United States for the Interstate System after July 31, 1959, unless the Secretary of Commerce (in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury) determines that funds will be available in the Trust Fund as the amounts needed to satisfy such obligation will be payable. A repayable advance shall be made to the Trust Fund to provide for satisfaction of obligations incurred by the United States before August 1, 1959. No amount may be expended out of the Trust Fund for an obligation of the United States incurred after July 31, 1959, for the Interstate System until all such advances have been repaid.”[14]

This immediate program cutoff, which provided no new revenue, failed by the narrowest of margins – 11 yeas, 12 nays. The panel then recessed for the day, to resume on July 29. At that point. Rep. Frank Ikard (D-TX) proposed a combination of Trust Fund revenue bonds, general revenue diversion, and program cuts and slowdowns:

That there be issued not to exceed $1 billion of bonds outside the debt limit, and against the assets of the Trust Fund, sometime before June 30, 1961; that the bonds be repaid sometime prior to June 30, 1966; that there be transferred to the Highway Trust Fund 2% of the existing 10% of the automobile excise taxes beginning July 1, 1961, for a period of four years; that a recommendation be made that the program be stretched out until June 30, 1976, and that allocations for the fiscal years 1960 and 1961 be reduced from $2.5 billion to $600 million and $1.4 billion, respectively, and that subsequent apportionments be reduced to meet the revenues provided.[15]

Before Ikard’s motion could receive a vote, Rep. Harrison offered an amendment to clarify that the bonds would be part of the public debt and therefore subject to overall debt limitation, which was defeated by a vote of 10 yeas, 14 nays. Then Ikard’s motion was agreed to by a vote of 15 yeas, 10 nays, and became the official recommendation of the Ways and Means Committee.

Mills promptly issued a press release announcing the program (and correcting that Ikard meant to reduce the 1961 and 1962 apportionments, not 1960 and 1961) and stating “This action by the Committee results from the feeling on the part of the Committee that the American people would prefer to spread out the construction and payment of the Interstate Highway System over four additional years to an increase of 50 percent in the tax on gasoline and other motor fuels, as proposed by the President in order to permit the construction of the highway program within the time originally contemplated.” (The press release and draft bill and committee report can be read here.)

What was not explicit in the press release was that, implicit in the four-year extension was also an invitation to the Public Works Committee to increase funding authorizations for the Interstate system by $10 billion in order to meet the revised January 1958 cost estimate.

Simpson and Byrnes promptly issued their own statement saying that the bonding proposal was “lacking fiscal morality and as abdicating our responsibility to pay our own way” and calling it “a raid on the Treasury and future taxpayers at a time when the Federal Government is already confronted with serious fiscal and debt management problems.”[16]

The proposal did not go over well at the White House, either. At a July 31 Cabinet meeting, Treasury Secretary Anderson described the Ways and Means plan and “With the President’s support, he spoke strongly against any kind of debt-financing of the highway program in a period of such prosperity as the country is now enjoying.”[17]

At the Bureau of the Budget, highway analyst Paul Sitton (who would later go on to head the Urban Mass Transportation Administration) sent his bosses a memo on August 3 saying that “The action of the House Ways and Means Committee does not accord with the Administration’s recommendations. We are under the impression that the bond proposal is unacceptable.”

Sitton said that the Commerce and Finance Division of BoB recommended that they immediately activate the contingency plan to shut down the incurring of all new highway obligations for a period of 30 to 60 days and that the Bureau of Public Roads field offices start telling each state highway department how long they were going to have to wait to get reimbursed during FY 1960 and 1961 for costs already incurred.[18]

Budget Director Stans hand-wrote a reply that “Negotiations are still pending and a tax is still a distinct possibility. Please hold off until final action by the Congress. Bring up again Aug. 15 or 20.”[19]

Public Works rejects Ways and Means plan

The Ways and Means plan was quickly rejected by the key Senator on HTF financial issues. Finance Committee chairman Harry Byrd (D-VA) entered the fray on August 6, submitting a statement in the Record (here starting at page 15263) to say that he was “vigorously and unequivocally opposed to the billion dollar bond issue” in the Ways and Means bill and also to any further suspension of the pay-as-you-go requirement that bore his name.[20]

However, it was beginning to look like the Eisenhower Administration’s strategy of starving the states in order to get state governors to back down from their opposition to a gas tax increase was beginning to produce results. The annual meeting of the Governor’s Conference was held August 2 – 6 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The governors adopted, by voice, a resolution stating that “the financing of highway construction is considered to be the number one problem facing the states for which an effective solution must be found” and that “the President and Congress are respectfully urged to come to an agreement on a program to provide sufficient funds to meet the current federal highway fiscal crisis.”[21]

By this point, Robert Merriam had left the Budget Bureau to become President Eisenhower’s special assistant for intragovernmental affairs – Ike’s liaison to governors and mayors. (Merriam had been a Chicago alderman and was actually the Republican nominee for mayor in 1955 but was defeated by the Democratic nominee, Cook County Clerk Richard J. Daley, who then went on to become mayor-for-life.) Merriam was at the San Juan conference and later reported back to the White House that at the conference “there finally developed a full appreciation of the problem and that many Governors indicated privately that they would forego opposition to the gasoline tax increase.”[22]

The Ways and Means bonding bill was not ready to go to the House floor yet. In 1959, just like today, jurisdiction over the highway program was split. Ways and Means controlled the Highway Trust Fund itself, and the taxes deposited therein, but the Public Works Committee controlled the spending side of the equation, and neither could write a bill changing the apportionment and revenue schedule without the other. But each committee had to write a bill that assumed the other committee would make certain policy choices. The Ways and Means press release announcing its bill included language that “…the committee recommend that the Public Works Committee” stretch out funding authorizations through 1973 and lower the FY 1961 and 1962 Interstate authorizations.

On the Monday after the Ways and Means markup (August 3), some of the Republican members on House Public Works went to the White House and discussed a possible 1 cent per gallon fuel tax increase for FY 1960 and 1961, with Interstate authorizations lowered from $2.5 billion per year to $1.6 billion per year in each of those years. A Budget staffer wrote, “The above alternative would entail a slow-up in the program and a partial waiver of the Byrd amendment. It will not eliminate the trust fund deficit without the imposition of definite administrative control over obligation (approval of contracts) and deferment of payments to the states to liquidate contracts.”[23]

Later that day, Under Secretary Allen met with seven of the twelve Republicans on House Public Works, led by Russell Mack (R-WA), the 2nd-ranking minority member of the panel, in Mack’s office. According to Allen’s notes, “The proposal that seemed to interest the Congressman most was one cent for three years…”[24]

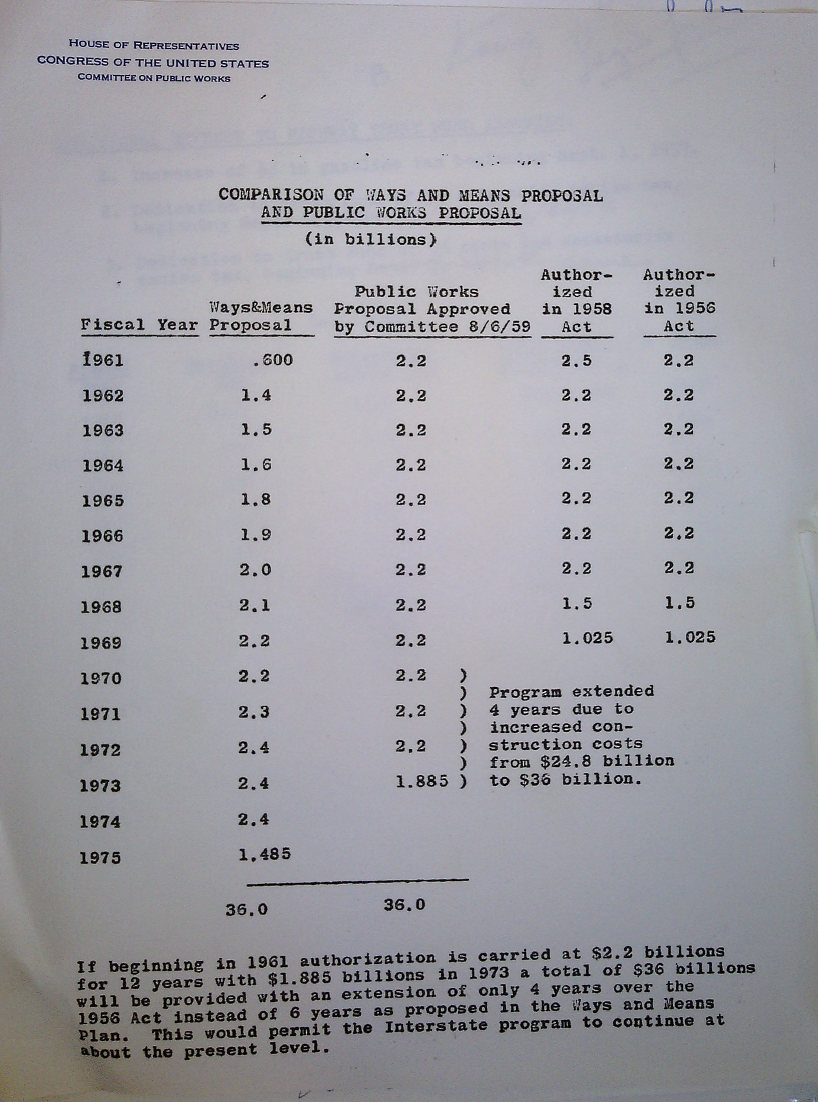

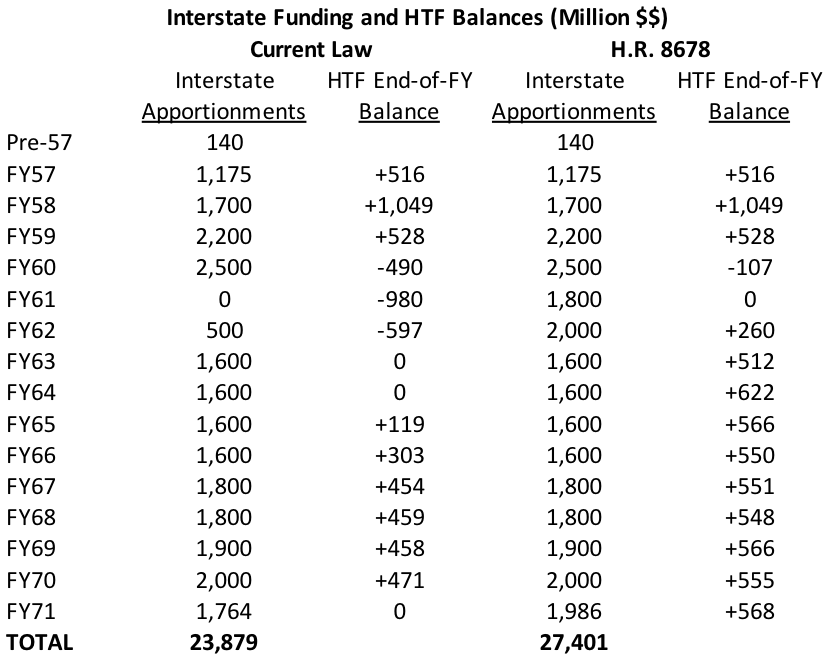

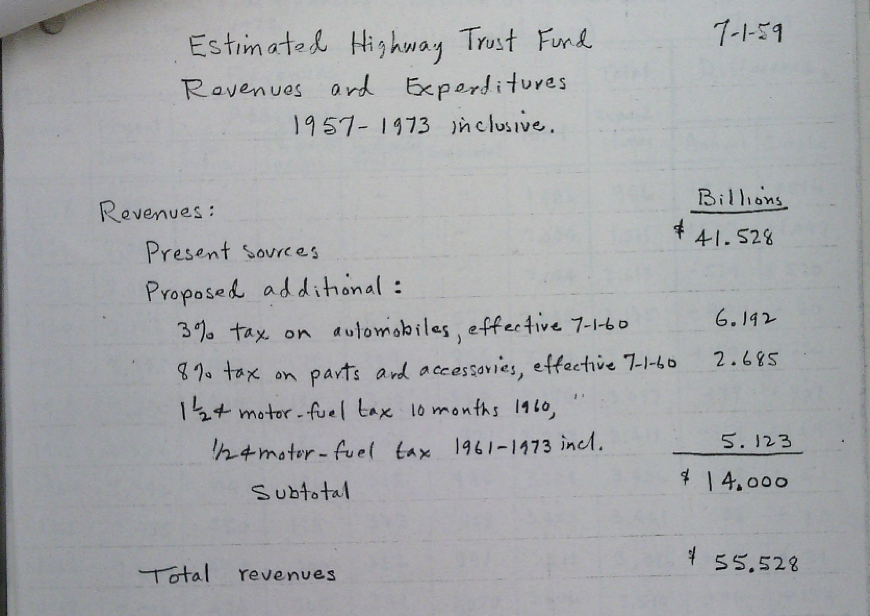

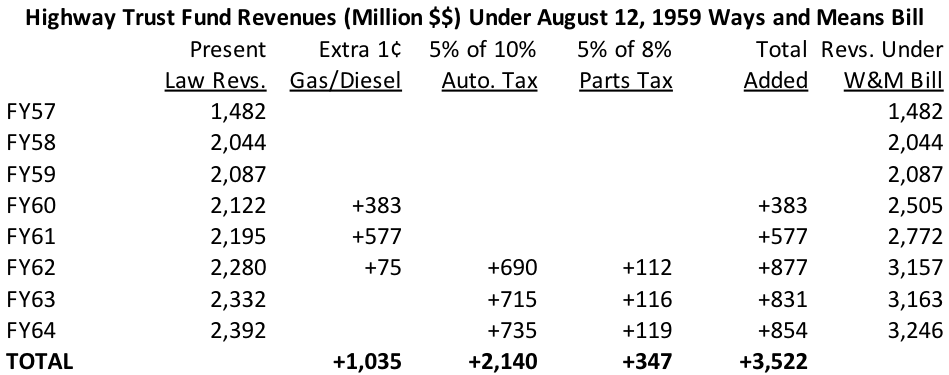

On August 6, House Public Works, led by chairman Charles Buckley (D-NY), refused to go along with the Ways and Means plan. Instead, the committee adopted a plan that maintained $2.2 billion per year authorizations through 1967, as in current law, and then kept going at $2.2 billion per year through 1972 instead of trailing off as under current law. Public Works then started circulating a table showing how their authorizations for a $36 billion Interstate system were steadier, and could finish construction years more quickly, than the extrapolated Ways and Means proposal.

The Public Works table conveniently ignored the fact that Public Works had no way to pay for its plan. An internal Budget Bureau menu dated that afternoon said that Public Works “are going to pass the responsibility for financing this program to the Ways and Means Committee,” noted that it would need at least $800 million per year in new tax revenues, and concluded that “This proposal seems so controversial and unrealistic that we are not going to prepare any refined estimates of the financial implications unless you [Director Stans] direct.”[25]

Ways and Means reconsiders, adopts gas tax

Ways and Means brought the highway issue back up at its Monday, August 10 executive session. Rep. Byrnes offered a one cent tax increase for two years, which failed by a vote of 8 yeas, 15 nays. Early the following morning, the White House hosted the regular meeting between President Eisenhower and Congressional GOP leaders. Byrnes told the group that Democrats were divided on the bond issuance, and that “many of the members would settle for a ¾¢ increases but that it would be not sufficient to allow any new allocations of funds for 1961.”[26]

Senate Minority Whip Thomas Kuchel (R-CA) said that even if the House passed a bill without a gas tax increase, “the Senate might give approval to a 1-½¢ increase on a new vote; this could be accomplished by amendment if the House sent a bill to the Senate.” At the end of the meeting, “It was agreed that the Administration effort would continue for increased revenues.”[27] A memo from the Treasury Secretary to the new White House chief of Staff, Gen. Wilton Persons, later that day suggested a plan that would have a 1 cent fuels tax increase for 1960 and 1961 plus the option for the Administration to transfer a portion of the auto excise tax for fiscal years 1962 and 1963 if the overall federal budget was showing a surplus large enough to spare the money from the general fund.[28]

The Ways and Means Committee reconvened in executive session later on the 11th to keep the discussion going. The panel wound up rejecting five different plans:

- Simpson (R-PA) 1½ cent increase for FY 1960, 1 cent increase for FY 1961-1964 – failed, 8 yeas to 17 nays.

- King (D-CA) ½ cent increase (immediate), plus diversion of 8 percent auto parts tax and 3 percent automobile tax from FY 1962-1964 – failed, 10 yeas, 15 nays.

- Machrowicz (D-MI) $1 billion revenue bond plan plus ½ cent increase for fiscal years 1960-1964 – failed, 9 yeas, 16 nays.

- Baker (R-TN) 1 cent increase, FY 1960-1964, with an additional ½ cent added for FY 1961-1964 – failed, 10 yeas, 15 nays,.

- Baker (R-TN) ¾ cent increase from FY 1960-1964 – failed, 9 yeas, 16 nays.

- Byrnes (R-WI) 1 cent increase for FY 1960-1961, plus diversion of 5 percentage points of automobile excise tax and 5 of the 8 percentage points of parts and accessories tax for FY 1962-1964 – failed, 13 nays, 12 yeas.

The vote on the final Byrnes motion was close, and bipartisan: 6 Democrats and 6 Republicans in favor, 9 Democrats and 4 Republicans against. A story in the Baltimore Sun the following morning noted that “Some believed that because of the one-vote margin this plan may yet provide the basis for a bill which can be sent to the floor of the House,” but that “Intimations from several congressional sources today were that the Democratic leadership is waiting for the governors to give them a further signal as to whether a limited increase of the gas tax for a stated period will be acceptable…”[29]

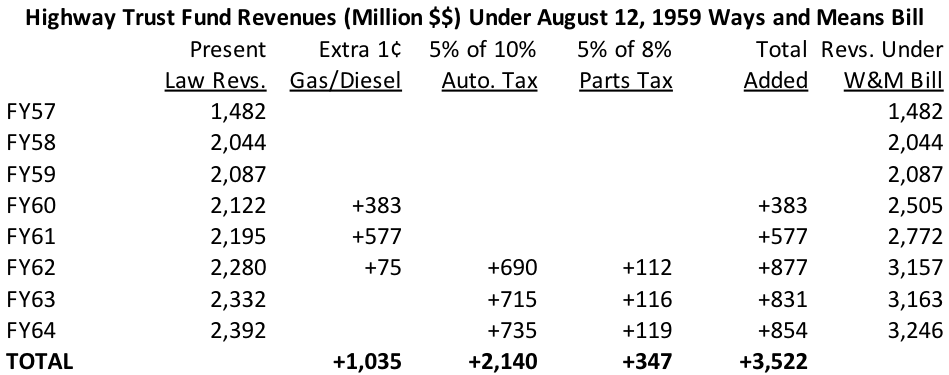

After spending August 12 handling other legislation, Ways and Means returned to highways on August 13 and reversed course by adopting Byrnes’ final motion from August 11 by a vote of 19 to 9. 2 Democrats and 2 Republicans had changed their position from two days prior, so the plan that was approved by the committee had truly bipartisan support: 8 Democrats and 8 Republicans, with 7 Democrats and 2 Republicans opposed. It would be enough to apportion $1.8 billion for Interstates in FY 1961, $2.0 billion in FY 1962, and $2.2 billion in 1963 without waiving the Byrd Test.

According to the draft committee report that Ways and Means sent to Public Works after the markup, their plan would raise $1.0 billion in additional gas tax revenues and would also divert $2.5 billion of dedicated general revenue taxes to the Trust Fund.

The White House was willing to accept the Ways and Means deal. In his preparation for his August 12 press conference, the notes given to President Eisenhower said “The Administration will accept a one cent a gallon increase.”[30] (None of the reporters at the press conference asked about the highway situation.)

Public Works rejects Ways and Means plan (again)

But then nothing happened. Ways and Means had to wait for Public Works. The chairman of that panel’s Roads Subcommittee, George Fallon (D-MD) publicly supported the Ways and Means plan[31], and on August 14, he introduced the legislative language that chairman Mills gave him as part of a new bill (H.R. 8678. 86th Congress) that the Speaker then immediately referred to Public Works. (Fallon had added a reduction in the 1961 Interstate authorization from $2.5 billion to $2.0 billion and an approval of the 1962 Interstate cost estimate to the introduced bill as well.)

But George Fallon wasn’t the chairman of Public Works – Charles Buckley (D-NY) was, and he had other ideas.

Buckley’s top highway priority was a bill (H.R. 6303, 86th Congress) to spend $4.3 billion in federal dollars to reimburse states that built toll or free highways between 1947 and 1957 that were then included on the Interstate System for the cost of building those roads. This was a thorny issue that the 1956 Act had successfully dodged. Naturally, the $4.3 billion would go primarily to the big toll road states – New York would get 18.6 percent of the money, Illinois 9.6 percent, New Jersey 7.0 percent, Pennsylvania 6.6 percent, et cetera. Public Works had approved Buckley’s bill earlier that year but never filed the report.

And coincidentally, New York had, less than 6 months beforehand, enacted a controversial increase in its own gas tax from 4 to 6 cents a gallon, making its legislators even more skittish than average on a new federal tax increase.

So Buckley just sat on the bill and did nothing. Meanwhile, the session continued to wind down – Congressional leaders had promised an early September adjournment, and President Eisenhower’s announcement that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev would visit the United States for two weeks beginning on September 15 gave Congress a hard deadline, because only by adjourning sine die before that point could they avoid an unpleasant debate on whether or not to invite Khrushchev to address a joint session.

After a week of delay, nine of the Republicans on Public Works filed a written request for chairman Buckley to hold a meeting to consider H.R. 8678, with Russell Mack telling journalists that Buckley was conducting a “one-man filibuster” of the gas tax bill.[32] (The New York Times pointed out that the three Republicans on Ways and Means who did not sign the request for a meeting were all from Buckley’s home state of New York, and that Bob Jones (D-AL) had an alternate plan for a one-year, ½ cent tax increase, coupled with complete diversion of the automobile tax from general revenues, which Democrats might rally around.)[33]

At one point, it appeared that 21 of the 22 Democrats on Public Works (all save Fallon) opposed the Ways and Means plan, and were insistent that they be allowed to offer the Jones tax plan on the House floor as an amendment, which would have been a major slap at Ways and Means, which had enjoyed a special tradition of having “closed rules” preventing any amendments while the House considered its bills.[34] But the press also reported that “Committee sources disclosed that Buckley is holding off pushing for a decision on the highway legislation while he endeavors to get backing from the members for [his $4.3 billion reimbursement legislation].[35]”

The Speaker tries to broker a compromise, but Ways and Means wins

Speaker Rayburn had to get personally involved. On Friday August 21, the Speaker called a meeting with all of the Democrats on Public Works for Monday the 24th. The press billed the meeting as a “showdown.”[36] At that meeting, Rayburn was able to convince 18 of the 22 Public Works Democrats to back a compromise plan for a one-year, one cent gas tax increase, with a four-year diversion of half of the automobile tax and two-thirds of the auto excise tax from FY 1961-1964. Rayburn said that while he had opposed the tax increase in the past, “We’ve reached the point now where we’ve got to get some money from some source.”[37]

But neither Public Works nor the Speaker had jurisdiction over the tax code – Ways and Means did. And Wilbur Mills called a special meeting of the committee to be held on August 25. Earlier on the 25th, at the regular White House legislative meeting, John Byrnes told the group that “Congress would have to act to save the program,” though Everett Dirksen was still pessimistic about a gas tax in the Senate and Charlie Halleck was still opposed to any diversion of general revenues.[38]

At the Ways and Means executive session, a bare majority of the panel voted to reject the Speaker’s compromise – it failed by a vote of 12 yeas, 13 nays, with 9 Republicans and 4 Democrats voting “no” and holding out for the longer duration gas tax which the panel had originally approved. They even took the further step of directing chairman Mills to introduce the tax provisions as a new bill that they could use to go straight to the House floor, bypassing the Public Works Committee, the Rules Committee, and the Speaker using the privilege that Ways and Means enjoyed at the time. (Mills introduced the bill as H.R. 8810, 86th Congress.)

Shortly after the Ways and Means vote, President Eisenhower sent Congress a special message stating that he was about to leave for Europe the following day on a trip that would last until September 7. The message listed two pending issues so urgent they needed to be addressed by Congress in his absence: mortgage loan insurance reauthorization, and highways. Eisenhower used the opportunity to give public support for the Ways and Means plan:

The recent action by the Ways and Means Committee of the House of Representatives in approving an increase of I¢ for two years represents a step in the right direction. Although it would mean some slowing down of present construction rates, a 1 cent tax increase would allow a reasonable rate of progress to be maintained.

A small increase in the tax on gasoline is the best way to put the Interstate Highway Program on a self-supporting pay-as-you-go basis. I must express again my objection to proposals that would, in the absence of foreseeable budget surpluses, divert receipts from the General Fund of the Treasury that are collected from various excise taxes on automobiles. The transfer of these receipts to the Highway Trust Fund would only shift the fiscal problem from the Highway Trust Fund to the General Fund, which is already in precarious balance. I should also make dear that I do not favor proposals that would finance anticipated deficits in the Highway Trust Fund over the next several years by the issuance of bonds.[39]

On August 27, Wilbur Mills addressed a closed caucus of Public Works Democrats. At the meeting, according to the Wall Street Journal, “Public Works Committee Chairman Buckley (D-NHY) said he saw no choice but to accept the Ways and Means Committee plan or lose jurisdiction altogether. On a voice vote most of the Public Works Committee Democrats agreed to back the plan,” and they agreed that Public Works would mark up H.R. 8678 (the clean Fallon bill that had been introduced August 14) on the following Tuesday, September 1.[40]

At the Public Works markup, chairman Buckley did manage to save some face by having the panel add one amendment to H.R. 8678 – a new section expressing the “intent and policy of the Congress” to reimburse the states whose toll and free roads had been incorporated into the Interstate. No amendments were made to the portion of the bill that had been recommended by Ways and Means. In the joint report (House Report 1120, 86th Congress), ten of the Public Works Democrats filed supplemental views opposing the gas tax increase, saying that the Eisenhower Administration’s underlying purpose was “to provide a surplus in the general budget at the expense of the highway user.”[41]

The bill got a hearing before the Rules Committee the following day and the panel granted a closed rule – no amendments could be allowed from the floor except for the one that Public Works recommended for Buckley – but the Buckley amendment would not be “self-executed” by the adoption of the rule but instead would have to be offered on the floor and voted on by the House.

House floor debate and passage

The House took up the closed rule on H.R. 8678 on September 3, and it quickly became apparent that the fix was in. The Constitution says that a roll call vote in Congress can only be ordered by the demand of at least one-fifth of those members present (except on veto override votes, where the yeas and nays are mandatory), but also, a majority quorum has to be present as well, or else a member can demand a live quorum call. Significant numbers of House members stayed on the floor throughout debate, so when opponents of the closed rule asked for a recorded vote on a delaying procedural motion, the Speaker pro tem was able to count 223 members in the chamber (a quorum), and fewer than 45 of them supported the demand for a roll call vote, so the motion passed by voice. Then, the rule itself was adopted in a similar manner – by voice vote, since over four-fifths of a quorum did not want to have a roll call. This is almost always a sign that the leaders of both parties share the same position and don’t want a roll call vote.

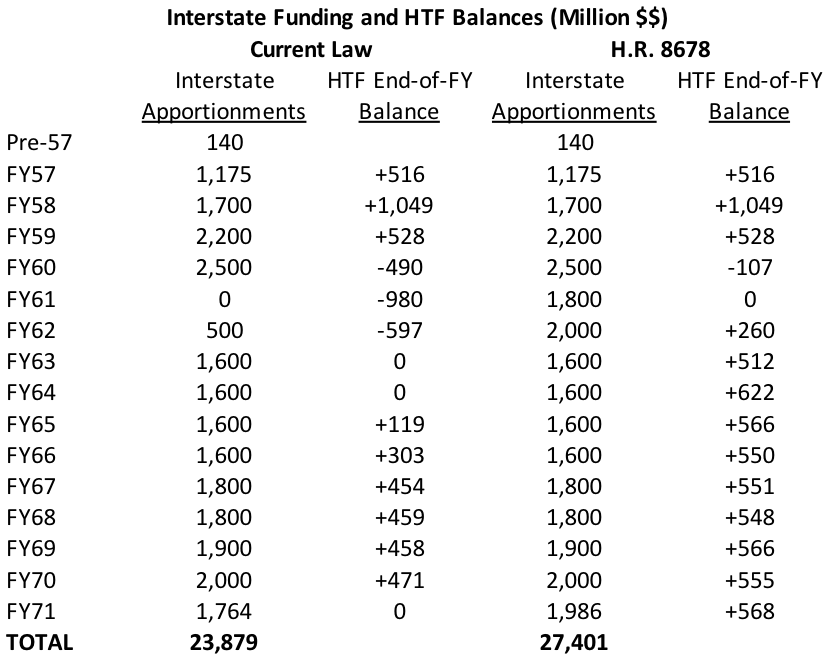

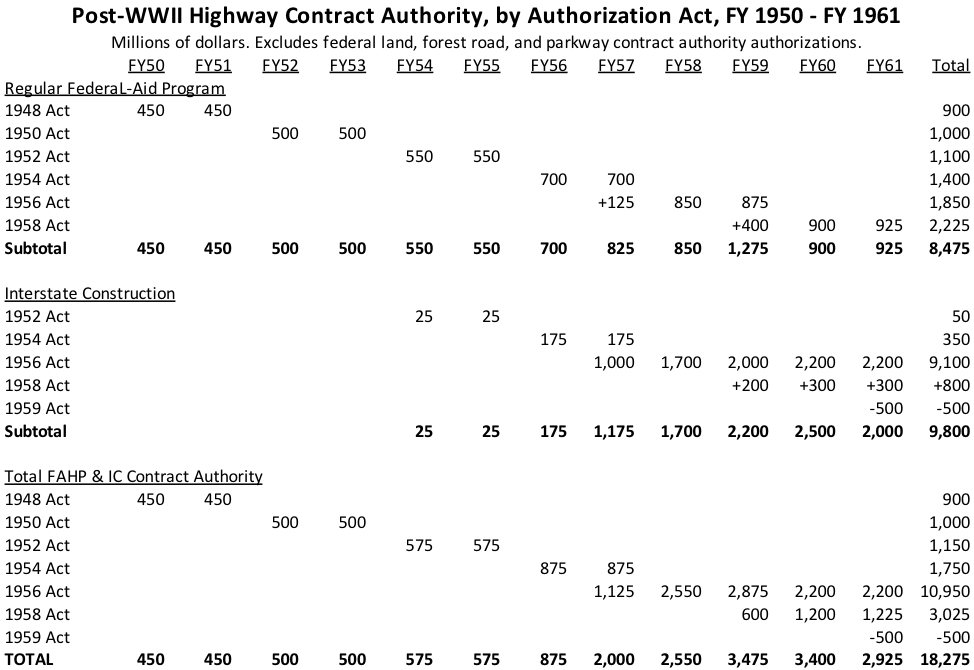

During debate on the bill itself, Fallon made clear that the bill was “temporary, emergency legislation. It meets the immediate problem. It leaves the way clear for a revision of highway financing legislation in 1961, when the appropriate studies will become available. The bill provides for reasonable progress during the interim period.”[42] The table provided by Ways and Means and printed as Table 3 in their part of the committee report (reproduced below) shows that the financing package was only designed to keep the program going at something approaching authorized levels through fiscal year 1962 apportionments – starting with FY 1963 apportionments, which were due to be made in summer 1961, funding was still going to be Byrd Tested downwards to $1.6 billion per year. But the next Congress, and the next President, would be given new cost allocation studies and cost estimates in January 1961 and could make different decisions.

After three hours of wide-ranging debate, the clerk called up chairman Buckley’s reimbursement amendment. Russell Mack led the opposition and simply pointed out how much more money the handful of big toll road states were going to get compared to the rest of the country. Buckley’s amendment failed by a division vote (basically a show of hands), 87 yeas to 144 nays, and then Buckley demanded “tellers” (an old form of anonymous but more reliably well-counted voting), and his amendment failed again, 98 yeas to 170 nays. Buckley did not try to demand a roll call vote, as he could sense by that point the sentiments of the House.

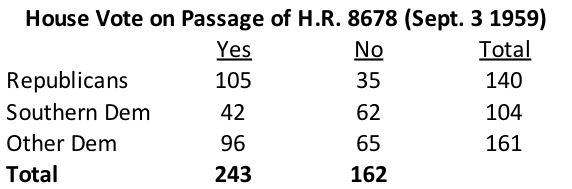

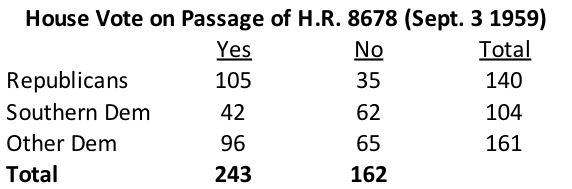

Then, after a motion to recommit (without instructions) was defeated by voice, H.R. 8678 passed by a vote of 243 yeas, 162 nays. 75 percent of Republicans voted for the bill, while Southern Democrats split 42-62 against the bill and other Democrats split 96 to 65 (which meant 60 percent of them supported the bill).

Senate committees act (quickly)

When the House transmitted H.R. 8678 to the Senate the following day, Majority Leader Johnson called up the bill and asked that it be referred to the Public Works Committee, then recessed the Senate so that Public Works could hold a quick markup session in a nearby room. (Sen. Wayne Morse (D-OR) was objecting to the unanimous consent needed for committees to meet during the Senate session because he was upset over unrelated issues.) When they reported the bill, Johnson then quickly gained unanimous consent to re-refer the bill to the Finance Committee, which held its own brief meeting and agreed to file its own report.

Public Works had added billboard, parkway, and emergency relief provisions to title I of the bill (as well as a study of the need for highway mileage for the new states of Alaska and Hawaii). Finance, pivotally, did not amend the essence of the revenue title – they only added a few clerical date changes (recognizing that it was too late for the gas tax increase to take effect on September 1, they moved the date to October 1) and some technical re-definitions of gasoline “producer” and “distributor.”

If Finance had amended the gas tax or the general revenue tax diversions, and those amendments had passed the Senate, then it would have (theoretically) been possible for opponents in the House to get a clean, up-or-down vote on those provisions when the bill went back to the House, without having to vote against the entire package. But by refusing to amend those parts of the bill, Byrd was putting the gas tax increase beyond the reach of House opponents – if he could get the bill through the Senate without amendment.

Byrd also managed to hold a hearing on the bill during September 4. Highway Administrator Tallamy, Budget Director Stans, and an Assistant Treasury Secretary all testified, but once again, almost all of the questions were for Tallamy. The Administrator said that, while H.R. 8678 would permit Interstate apportionments to go out at $1.8 billion for 1961 and $2 billion for 1962, and non-Interstate apportionments to go out as normal, “it will be necessary for the Bureau of Pubic Roads to exercise control of obligations so that contract in the current fiscal year and for fiscal 1961 do not exceed the amounts apportioned in those years for both programs.”[43]

Budget Director Stans made it clear that the White House was “willing to accept this bill as a temporary measure” despite inadequate revenues and general fund transfers, and Assistant Treasury Secretary Laurence Robbins added that “Treasury while not approving H.R. 8678, will accept it reluctantly in the hopes that as a result of continued study, and after the Commerce Department’s plans have been submitted, a satisfactory plan for permanent financing of the highway system can be devised which will eliminate the revenue transfers proposed in the bill.”[44]

Al Gore (D-TN) got into a long back-and-forth with Tallamy trying to divine the precise legal justification for Public Roads to add some kind of artificial post-apportionment contract controls. The BPR General Counsel said that the authority was implicit in three provisions of the newly codified title 23 U.S.C.: sections 105 (the Secretary “may approve a program [of proposed highway projects in a state] in whole or in part,” 106 (where the Secretary has approval power over each proposed project), and 110 (where the Secretary has to sign proposed project agreements).

Tallamy also made it clear that the contract controls would be voluntary, in a sense: “we would advise the States that this would be necessary if we are to pay them on time. Now, if a State wants to go ahead within the amount of apportionments that have been made, recognizing that the trust fund will not be able to support their payment when they submit the voucher to us, we, under those circumstances, of course, would not tell a State they couldn’t go ahead. But it would obviously be necessary for us to say to a particular State, ‘If you want to be paid on time out of the trust fund within our ability to pay you, the amount of contracts under your apportionment that you can make this year is so much, and that is all. And if you go beyond it…”[45]

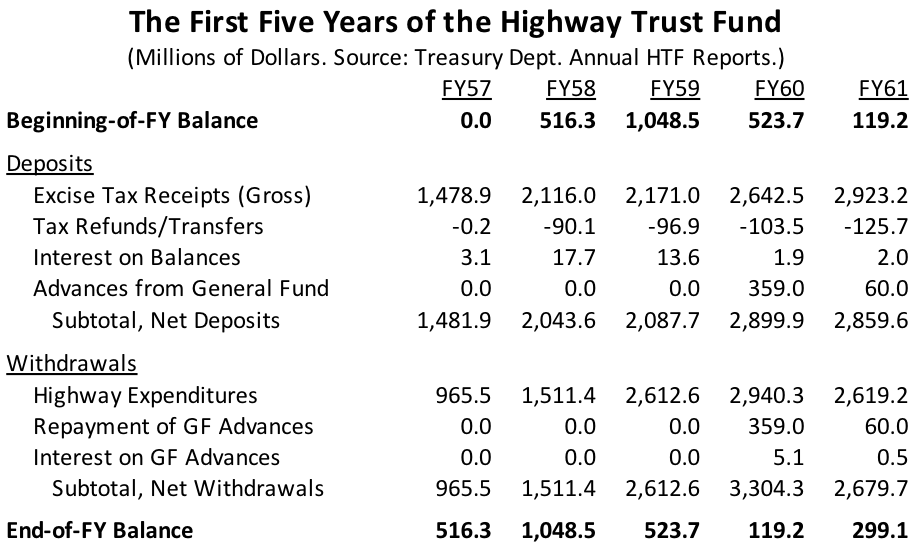

Gore also got Tallamy to admit that not only would the Trust Fund still require a “repayable advance” from the general fund under H.R. 8678 in order to avert mid-year insolvency in the Trust Fund, that the Commerce Department had already sent a request for such supplemental appropriation to the Bureau of the Budget.[46] (Indeed they had. An August 26 Budget memo indicates that they had received the proposed appropriation request for a $309 million temporary advance (“because 65% of the year’s expenditures occur in the first six months whereas only 48% of the year’s receipts are received during this same period”) but that “We have informally advised Commerce that we would not act on this supplemental pending clarification of the action of Congress on a revenue bill.”[47]

Senate floor debate and final passage

When the Senate convened at 11 a.m. on Saturday, September 5, Majority Leader Johnson brought up the highway bill. The first amendment offered was by Gore, who proposed to kill the gas tax increase and change the schedule of diverted general revenue taxes to only include 4 points of the automobile tax in FY 1960 and then 6 points in 1961-1964. This would add $3.9 billion to the Trust Fund ($370 million more than H.R. 8678), and to fill that $3.9 billion hold in the general fund, Gore’s amendment would have increased federal taxes on stock dividends.

Gore’s floor speech (starting on page 18207 here) was largely an attack on the entire user-pay concept – or, rather, the direct user-pay concept. Gore thought that those who received indirect benefits from roads should pay a portion of the cost of those roads – highway users should pay “a heavy portion of the cost, but I do not believe they should bear the entire cost, because there are so many other interests which benefit, including national defense, automobile companies, tire companies, and other industries which depend on highway transportation.”[48]

Richard Neuberger (D-WA) offered an amendment to Gore’s amendment to add back the 1 cent, 2-year gas tax, and after discussion, Johnson recessed the Senate from 5 p.m. to 6 p.m. so that Finance could have a short executive session with more Administration witnesses to discuss the overall situation. When the Senate came back, Neuberger withdrew his amendment and Minority Whip Kuchel had been able to get a revenue score of the Gore amendment from Treasury – Gore’s dividend tax would only raise $620 million in total, less than the $1.04 billion of motor fuel tax it was to replace and not even touching the $2.5 billion in existing taxes being diverted from the general fund to the Trust Fund.

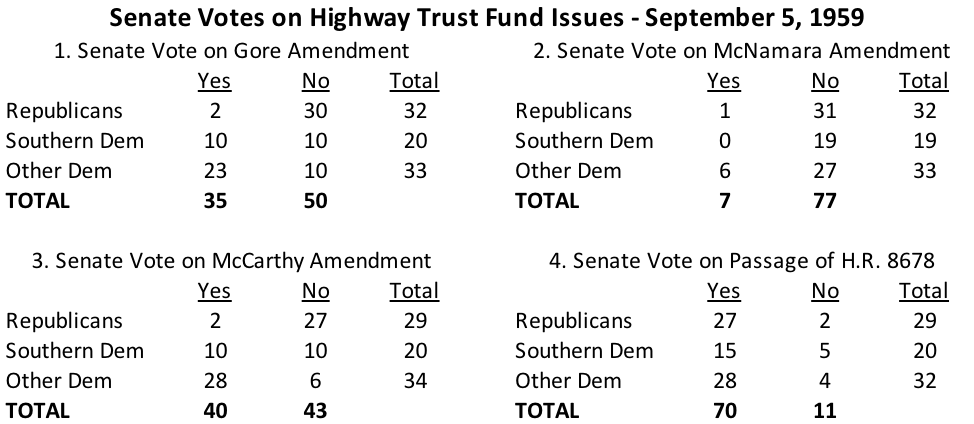

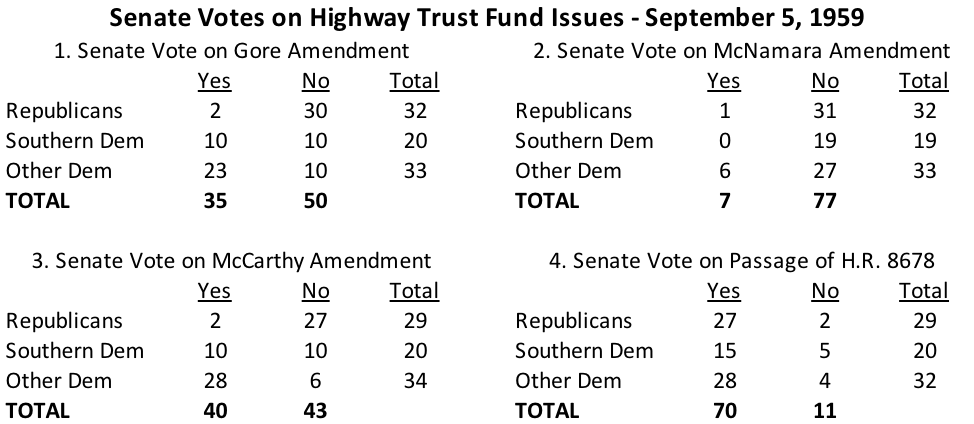

After further debate, Gore’s amendment lost by a vote of 35 yeas, 50 nays. Republicans were nearly unanimous (30 to 2 against Gore), Southern Democrats split 10 to 10, and other Democrats backed Gore, 23 to 10.

Two other finance-related amendments were offered. Roads Subcommittee chairman Pat McNamara (D-MI) offered an amendment to the revenue title on behalf of his home state auto industry, gradually phasing out the portion of the automobile excise tax that was to remain in the general fund. His amendment was rejected, 7 yeas to 77 nays. And Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) offered an amendment to retain the House-passed gas tax, reduce the amount of the transfer of general fund taxes to 2.5 points of the tax in FY 1960 and 1961, and then raise it to 6 percent for FY 1962-1964, and then use Gore’s dividend tax to make the general fund whole. Gore wound up supporting the amendment, but it, too, failed, 40 to 43 (again near-unanimous GOP opposition, Southern Dems equally split, and non-Southern Dems largely in support.

The Senate did not add any amendments to the revenue title of the bill (other than the minor amendments recommended by Finance), and just before midnight, the Senate passed H.R. 8678, as amended, by a vote of 70 to 11.

The whole thing ended quietly. As the first item of business when the House of Representatives convened at noon on September 9, Public Works chairman Buckley asked unanimous consent to agree to the Senate amendments to H.R. 8678. (The Senate had asked for a House-Senate conference and appointed conferees, but it would not be necessary.) Without objection, and without any debate whatsoever, the House agreed to the request, and the bill was cleared for President Eisenhower’s signature.

Sometimes, the House passes a bill by unanimous consent because it is broadly popular and because not a single member finds anything in the bill objectionable. Other times, they pass a bill by unanimous consent because the leaders of both parties just want to get it over with and have been successfully able to wear down the opposition. This was one of the latter instances.

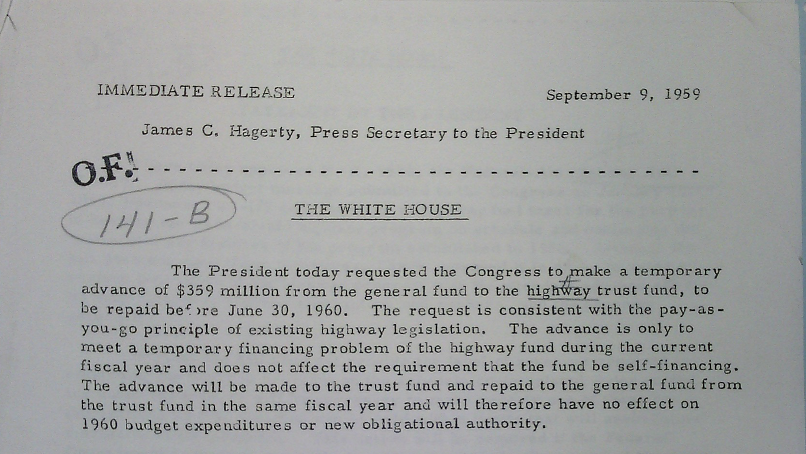

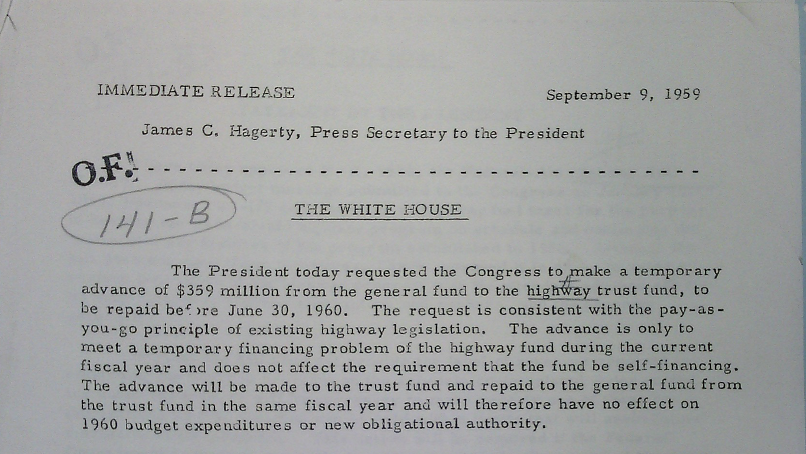

Bailout requested and approved

Once the White House received the phone call informing them that the House had cleared H.R. 8678 and it was too late for anything to go wrong, the official announcement was made: the President was requesting Congress to “make a temporary advance of $359 million from the general fund to the highway trust fund, to be repaid before June 30, 1960.”[49] The request did not seem to make the national news (people were preoccupied with Eisenhower’s veto of the public works bill that day, and whether or not it would become the first of Ike’s vetoes to be overridden, which it was).

The Budget Bureau had actually shared the language of the request informally with the Senate Appropriations Committee the previous day, because that was when the committee was marking up the last appropriations bill of the year (H.R. 8385, 86th Congress) – what was then called the “mutual security bill” (foreign aid), which was also the vehicle for the year-end supplemental appropriations package.

The Senate committee included the language precisely as requested by the White House: “For repayable advances to the ‘highway trust fund’ during the current fiscal year, as authorized by section 209(d) of the Highway Revenue Act of 1956 (70 Stat. 309), $359,000,000: Provided, That all such advances shall be repaid to this appropriation on or before June 30, 1960, and upon such repayment this account shall be withdrawn.” The committee report indicated that without an advance, the Trust Fund would hit a zero balance in October 1959.[50]

When the mutual security appropriations bill came to the Senate floor on Saturday, September 12, Al Gore raised a point of order against the advance to the Trust Fund because, he said, the proviso requiring the advances to be repaid by June 30, 1960 was not authorized by law (section 209 of the Highway Revenue Act specifically provided that advances were to be repaid whenever the Secretary determined money was available). Gore outsmarted himself – the Parliamentarian agreed that his point of order was valid, but Senate rules and precedents required that points of order against language in an appropriations bill had to strike the entire paragraph from the bill, not just the offending lines. Gore wound up striking the repayable advance from the bill entirely, so Mutual Security Subcommittee chairman Spessard Holland (D-FL) then had to offer a new amendment to H.R. 8385 adding back the $359 million payment, minus the offending repayment language. There was an extended discussion about whether or not the repayment of the advance should have priority over BPR repaying state vouchers, but Holland’s amendment wound up passing by voice.[51]

The Senate could not complete action on the appropriations bill on Saturday, and adjourned until just after midnight until Monday, September 14 – the last day of session, because it was the last day before Khrushchev came to town. It wound up passing by a vote of 64 to 25, and a House-Senate conference was requested. The House agreed to the conference at 11:15 p.m., and a conference report was filed at 3:25 a.m., which recommended that the House accept Senate amendment #42 (the $359 million HTF advance). The House agreed to the conference report without debate, 194 to 109, and then recessed again at 4:44 a.m. to give the Senate time to consider it. After the Senate then agreed to the conference report by voice vote, the House reconvened at 6:15 a.m. and adjourned sine die, (as the Senate did moments later) – six hours before Khrushchev’s plane landed at Andrews Air Force Base.

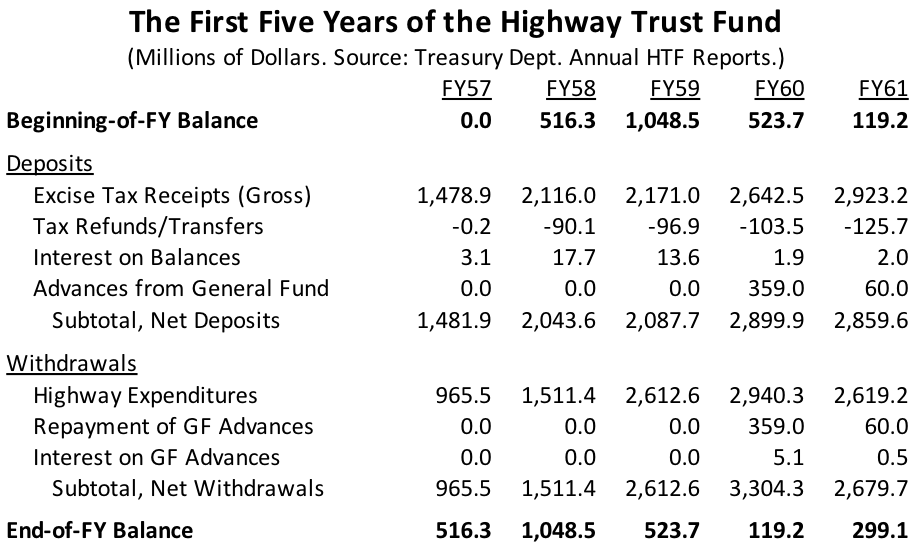

The mutual security bill was eventually signed into law on September 28 (Public Law 86-383), the full $359 million was promptly deposited in the Highway Trust Fund – and, true to the original promise, it was entirely repaid to the general fund (with interest) by the end of the fiscal year on June 30. For the next fiscal year (1961), the regular Commerce appropriations act (Public Law 86-451) appropriated an additional repayable advance of $160 million, but the Trust Fund did not wind up needing all of it – only $60 million was transferred, and once again, all of it was repaid by the end of the fiscal year, with interest.

No further bailouts were needed, save for $70 million in FY 1966, and when the Ways and Means Committee codified the Highway Revenue Act into the Internal Revenue Code in 1982, for some reason they repealed the provision authorizing repayable advances – which meant that were the Trust Fund ever to run out of money again, there would be no easy, temporary solution authorized by law.

Eisenhower signs the gas tax bill and implements cost controls

Congress formally presented the White House with the enrolled version of the HTF tax bill on September 10, giving the President ten days (not counting Sundays) to either sign it or veto it. As the official White House enrolled bill file on H.R. 8678 shows, there was never any question of the President vetoing the bill, but since the time-sensitive tax increase wasn’t going to take effect until October 1 anyway, there was no need to sign it before it became clear how the rest of the end-of-session business turned out.

Eisenhower signed the highway bill into law on September 21, 1959 (Public Law 86-342). His signing statement made clear what was about to happen to state highway departments, and why:

Because the bill does not provide the level of revenues required for continuing the highway program on the schedule contemplated under existing authorizations, it will be necessary to make orderly use of these authorizations so that spending can be held within limits that will avoid future disruption of the program. This action will be required if the Federal Government is to meet promptly its obligations to the States and at the same time adhere to the self-financing principle upon which the highway program has been established. Of necessity, such actions may lead to some deferment or delay in the completion of the Interstate System as originally contemplated.[52]

The Administration had been working on the plan for contract controls, coordinated by the Bureau of the Budget, since mid-July. On September 16, before the President signed the bill, the Bureau of Public Roads sent a preliminary memo to its regional engineers warning that “In order to assure that funds will be available to meet anticipated reimbursement requirements during the current and next fiscal years, it is necessary to provide for an orderly scheduling of obligations and contracts…obligations will be scheduled at an increasing rate during the year. Special accounting records are to be established to insure that obligation totals are not exceeded.”[53]

There was some back-and-forth between Commerce, BPR, and Budget in late September and early October as to precisely how the controls would work (Budget wanted BPR to be able to force states to prioritize certain types of projects, while BPR was adamant that all they could do was give states a total dollar amount). In the end, the official contract control circular was sent to states dated October 6, and the public announcement was made by the Commerce Secretary on October 8 (see both here).

Of the total (post-Byrd-test) FY 1961 apportionments – $900 million for ABC roads and $1.8 billion for Interstates, totaling $2.7 billion, states would collectively be able to obligate up to $600 million in the first quarter of the fiscal year, another $300 million in the second quarter, another $900 million in the third quarter, and a final $900 million in the fourth quarter. The notice included a table showing each state’s total apportionments and states were then given a multiplier – up to 22 percent in the first quarter, then 33, 67, and 100 percent of the total in successive quarters – that synced up with the overall $300-$600-$900-$900 million totals, but the individual state ceilings ensured that faster-spending states could not leave slower-spending states in the lurch.

As Tallamy had earlier indicated to Congress, technically speaking, the new contract controls were voluntary: “States desiring to proceed at a rate faster than can be supported from available Trust Fund revenues may elect to do so but with the clear written understanding that vouchers cannot be paid unless and until funds are available for reimbursement. Under current estimates of revenue and expenditures this cannot be expected to occur before late in the fiscal year 1963.”[54]

Contemporaneous with this announcement, the official apportionments were being made. The Commerce and Treasury Secretaries exchanged letters on October 7 confirming that the Byrd Test had been activated for the first time, and because of that, it was necessary to defer $200 million of the authorized $2.0 billion FY 1961 Interstate Construction apportionment until a later year. The $1.8 billion apportionment went out to states. (The $200 million in deferred funding was never apportioned – it was retroactively canceled by the 1961 highway act).

The Byrd Test would not be triggered again until FY 2004, whereupon Congress first waived the test temporarily (in section 10(d) of Public Law 108-280) and then, in section 11102 of the 2005 SAFETEA-LU law, amended the test so that the Trust Fund could actually run out of cash before the test was triggered. Which, of course, happened three years later.

Highway revenue issues were settled for the duration of the Eisenhower Administration. The next President would receive the long-in-the-making cost allocation report and an updated Interstate cost estimate in January 1961, which would enable them to work with Congress to make more long-term Trust Fund revenue decisions before the temporary 1 cent per gallon fuels tax expired, and the diversion of general revenues was to begin, on July 1, 1961.

[1] Memorandum (with attachments) from B.D. Tallamy to John J. Allen, Jr. dated July 2, 1959 with no subject line. Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, May, June. July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[2] John J. Allen, Jr., file memorandum dated July 2, 1959 with subject line “1½¢ TAX FOR PUBLIC ROADS.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, May, June. July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[3] John J. Allen, Jr. file memorandum dated July 6, 1959 with subject line “Financing Public Roads.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, May, June. July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[4] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – July 7, 1959.” Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (6) [July-September]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[5] Henry L. Trewhitt, “State Gets U.S. Warning on Road Aid,” The Baltimore Sun, July 16, 1959, p. 34.

[6] U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Ways and Means. “Highway Trust Fund and Federal Aid Highway Financing Program” (hearings held July 22, 23 and 24, 1959),86th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 4-5.

[7] Ibid p. 8.

[8] Ibid p. 37.

[9] Ibid p. 94.

[10] Ibid p. 95.

[11] Ibid p. 162.

[12] John J. Allen, Jr. file memorandum dated July 27, 1959 at 3:48 p.m. with the subject line “Financing Public Roads.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, May, June. July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[13] John J. Allen, Jr. file memorandum dated July 27, 1959 at 6:00 p.m. with the subject line “Financing of Public Roads.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, May, June. July 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[14] Copy of “Executive Sessions – Committee on Ways and Means To: Consider Financing of the Highway Trust Fund.” Located in the “HR 86A-D13 HR 8678 3 of 5” folder in Box 462 of the Papers Accompanying Bills and Resolutions, Committee on Ways and Means series of the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Joint Statement of The Hon. Richard M. Simpson (R-Pa.), The Hon. John W. Byrnes (R-Wisc.), U.S. House of Representatives” dated 6:00 p.m., July 29, 1959. Located in the “HR 86A-D13 HR 8678 3 of 5” folder in Box 462 of the Papers Accompanying Bills and Resolutions, Committee on Ways and Means series of the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

[17] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Minutes of Cabinet Meeting – July 31, 1959” p,. 4. Located in the “Cabinet Meeting of July 31, 1959 (1)” folder in Box 14 of the Cabinet Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[18] P.L. Sitton routing slip to Messrs. Bozman, Broadbent, Carey, and Stans dated August 3, 1959, covering an earlier memo dated July 21, 1959. Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[19] Ibid, Maurice Stans handwritten comments on routing slip.

[20] Congressional Record (bound edition), August 6, 1959 p. 15263.

[21] “Proceedings of the Governors’ Conference 1959 (Fifty-First Annual Meeting at San Juan, Puerto Rico, August 2-5, 1959)”published by the Governors’ Conference, Chicago, Illinois p .177.

[22] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – August 11, 1959.” Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (6) [July-September]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[23] Sam R. Broadbent file memo dated August 3, 1959 with the subject line “Alternative proposal for Highway fuel tax.” Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[24] John J. Allen, Jr. file memorandum dated August 3, 1959 at 4:02 p.m. with the subject line “Public Highway Financing.” Located in the “Highway – Financing – Legislative Br. Matters, Aug., Sept., Oct., Nov., and Dec. 1959” folder in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[25] Memorandum from Sam R. Broadbent to Budget Director Stans, dated August 6, 1969 with the subject line “House Public Works Committee action on highway program.” Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[26] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – August 11, 1959.” Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (6) [July-September]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Unsigned memorandum from the Treasury Secretary to General Persons (no subject line) dated August 11, 1959. Located in the “OF 141-B Highways and Thoroughfares (Roads (22)” folder in Box 612 of the White House Central Files in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Records as President, 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[29] “House Committee Defeats Series of Highway Financing Proposals,” The Baltimore Sun, August 12, 1959 p. 7.

[30] “Notes on pre-press conference, Gettysburg, August 12, 1959.” Located in the “Staff Notes Aug. 1959 (1)” folder in Box 43 of the DDE Diary Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[31] See Fallon’s statement in Rodney Crowther’s “House Group Approves 1-Cent Gasoline Tax Rise,” The Baltimore Sun, August 14, 1959, p. 1.

[32] John D. Morris, “’Gas’ Tax Action Pressed by G.O.P.,” The New York Times, August 22, 1959 p. 5.

[33] Ibid.

[34] John D. Morris, “’Showdown’ Is Set on Gasoline Tax,” The New York Times, August 23, 1959 p. 53.

[35] Rodney Crowther, “Speed Asked on Roads Bill,” The Baltimore Sun, August 21, 1959 p. 11.

[36] John D. Morris, “’Showdown’ Is Set on Gasoline Tax,” The New York Times, August 23, 1959 p. 53.

[37] Lew Haskins (Associated Press), “Caucus Backs Gas Tax Rise,” The Washington Post, August 25, 1959 p. A1.

[38] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Notes on Legislative Leadership Meeting – August 25, 1959.” Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1959 (6) [July-September]” folder in Box 3 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President (Ann Whitman File) 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[39] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to the Congress Urging Timely Action on FHA Mortgage Loan Insurance and on the Interstate Highway Program Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, retrieved September 8, 2019 at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/235261

[40] “House Works Unit Democrats Accept Gasoline Tax Rise,” The Wall Street Journal, August 28, 1959 p. 5.

[41] U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Public Works. “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1959 (Report to Accompany H.R. 8678) – printed as House Report 1120, 86th Congress, p. 6.

[42] Congressional Record (bound edition), September 3, 1959 p. 17954.

[43] U.S. Senate. Committee on Finance. “Highway Revenue Act of 1959 (Hearing on H.R. 8678), 86th Congress, 1st Session, p. 4.

[44] Ibid pp. 41-42.

[45] Ibid p. 34.

[46] Ibid p. 22.

[47] Memo from Budget Bureau Commerce and Finance Division (Pfleger) to Budget Director Stans dated August 26, 1959 with subject line “Current developments in Highway program.” Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[48] Congressional Record (bound edition), September 5, 1959 p. 18211.

[49] White House press release dated September 9, 1959. Located in the “OF 141-B Highways and Thoroughfares (Roads (22)” folder in Box 612 of the White House Central Files in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Records as President, 1953-1961 at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

[50] U.S. Senate. Committee on Appropriations. “Mutual Security and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 1960 (Report to accompany H.R. 8385)”. Printed as Senate Report 981, 86th Congress, p. 14.

[51] Congressional Record (bound edition), September 12, 1959 pp. 19326-19335.

[52] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Statement by the President Upon Signing the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1959. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, retrieved online September 8, 2019 at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/234252

[53] U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. Circular Memorandum to Regional Engineers dated September 16, 1959 with the subject line “Reimbursement Planning.” Located in the “Reimbursement Planning 1959” folder in in Box 15 of the General Records 1955-1963 of the Entry A1 26 Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation in the records of the Department of Commerce in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

[54] U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. Circular Memorandum to Regional Engineers dated September 16, 1959 with the subject line “Reimbursement Planning.” Located in a manila envelope labeled “P2-7/3 Sr. 52.1” in Box 96 of the Subject Files of the Director, 1962-1961 (52.1) series of the Records of the Bureau of the Budget at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.