(Some of this material was originally published in Transportation Weekly on October 10, 2007)

One hundred years ago this week, a Congressional conference committee consisting of House Appropriations Committee members and Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee members tried to decide whether or not to authorize, and/or appropriate, money for the federal-aid highway program for the upcoming year.

The conferees wound up creating a new budget concept, now called “contract authority” – an authorization for future appropriations that nonetheless behaves like an appropriation and allows the government to sign contracts and incur legal liability in advance of an appropriation being made. Contract authority has funded the federal-aid highway program ever since, and also funds most federal mass transit and airport programs as well.

Contract authority is only a few months younger than the centralized federal budget process itself, and was created in reaction to that budget process at a time when the power centers of Congressional finance were in flux. In order to understand the reasons why Congress created contract authority in 1922, it is first necessary to review the backstory of the fight for control over federal spending decisions.

Antecedents of executive spending power

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution declares that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law”. This provision was placed in the Constitution by the Framers to codify the “power of the purse” that the British House of Commons had painstakingly won from the Crown over the previous six centuries. As it reads, the provision seems clear: Congress must approve all federal spending through passage of an appropriations law.

However, there were conflicts from the very beginning over how much authority the President would have to enter into commitments that would later require appropriations. This was exacerbated in an era where Congress was only available for a two- or three-month session each year. The First Congress in 1789 passed a law (1 Stat. 54, sec. 3) directing the Secretary of the Treasury to sign contracts to build and man a lighthouse near the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay in advance of any appropriation.

More significant examples came about. The most famous, of course, is the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson agreed to a gigantic commitment of federal money without Congressional permission or appropriation, though Congress later passed a law making appropriations for part of the purchase and issuing bonds to pay for the rest. And Congress in 1799 first passed a version of a law that is still on the books – the Feed and Forage Act – that allows an army in the field to purchase supplies in the absence of an appropriation. The law (now at 41 U.S.C. §6301) allows the Defense Department (and the Coast Guard) to contract or purchase “clothing, subsistence, forage, fuel, quarters, transportation, or medical and hospital supplies” which “may not exceed the necessities of the current year.”

However, none of these antecedents really resembles modern contract authority. All were either for a specific sole purpose or else for an emergency contingency that is by definition impossible to plan for in advance. None of them were permanent federal programs designed to run on spending commitments in advance of appropriations.[1]

Appropriations decentralization

In 1802, the House of Representatives created a permanent Ways and Means Committee to consider all financial measures, and the Senate followed suit by creating a permanent Finance Committee in 1816. These committees had similar and broad jurisdiction over all revenue measures (taxes and tariffs), the public debt, appropriations bills, banking and currency.

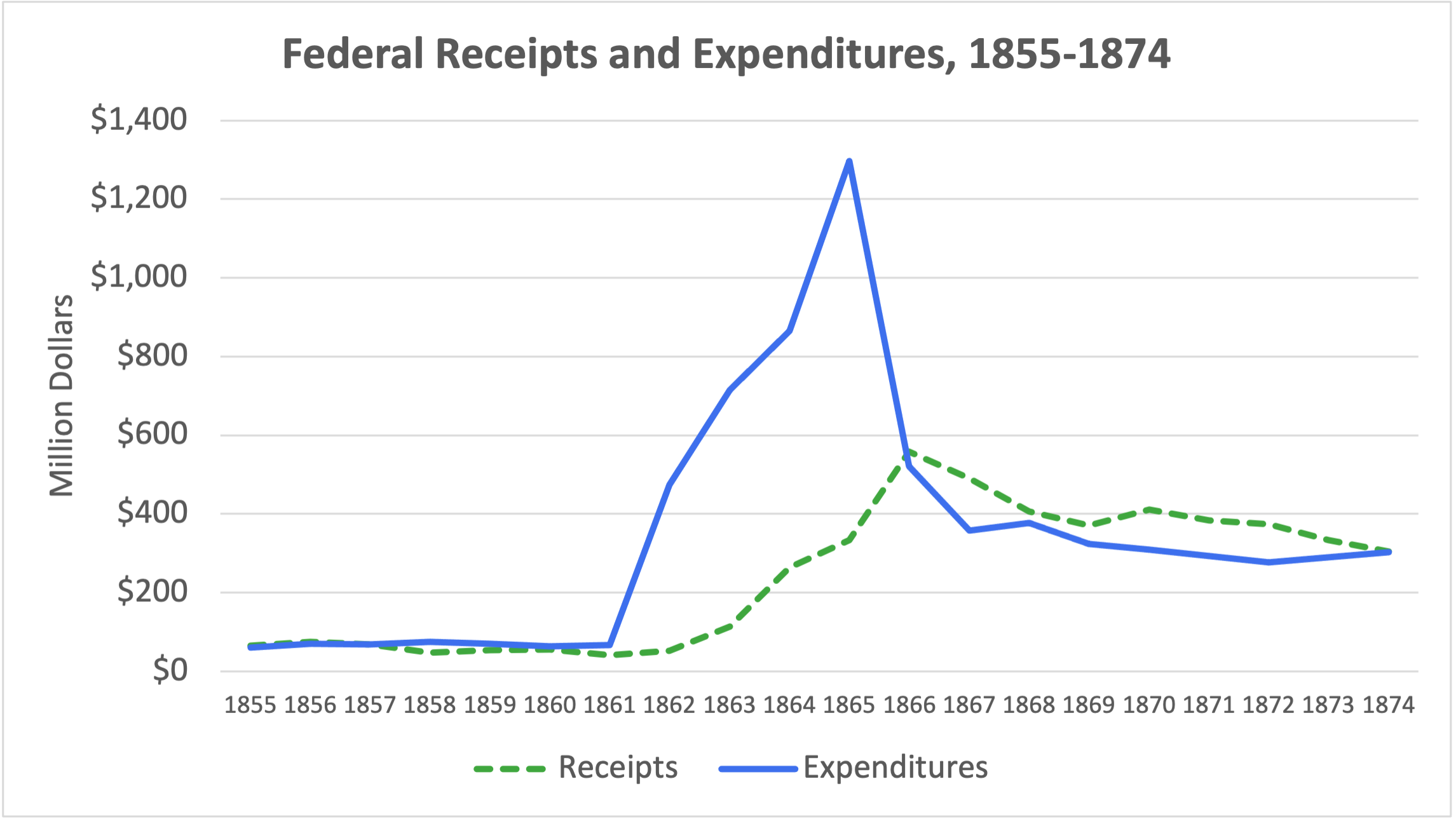

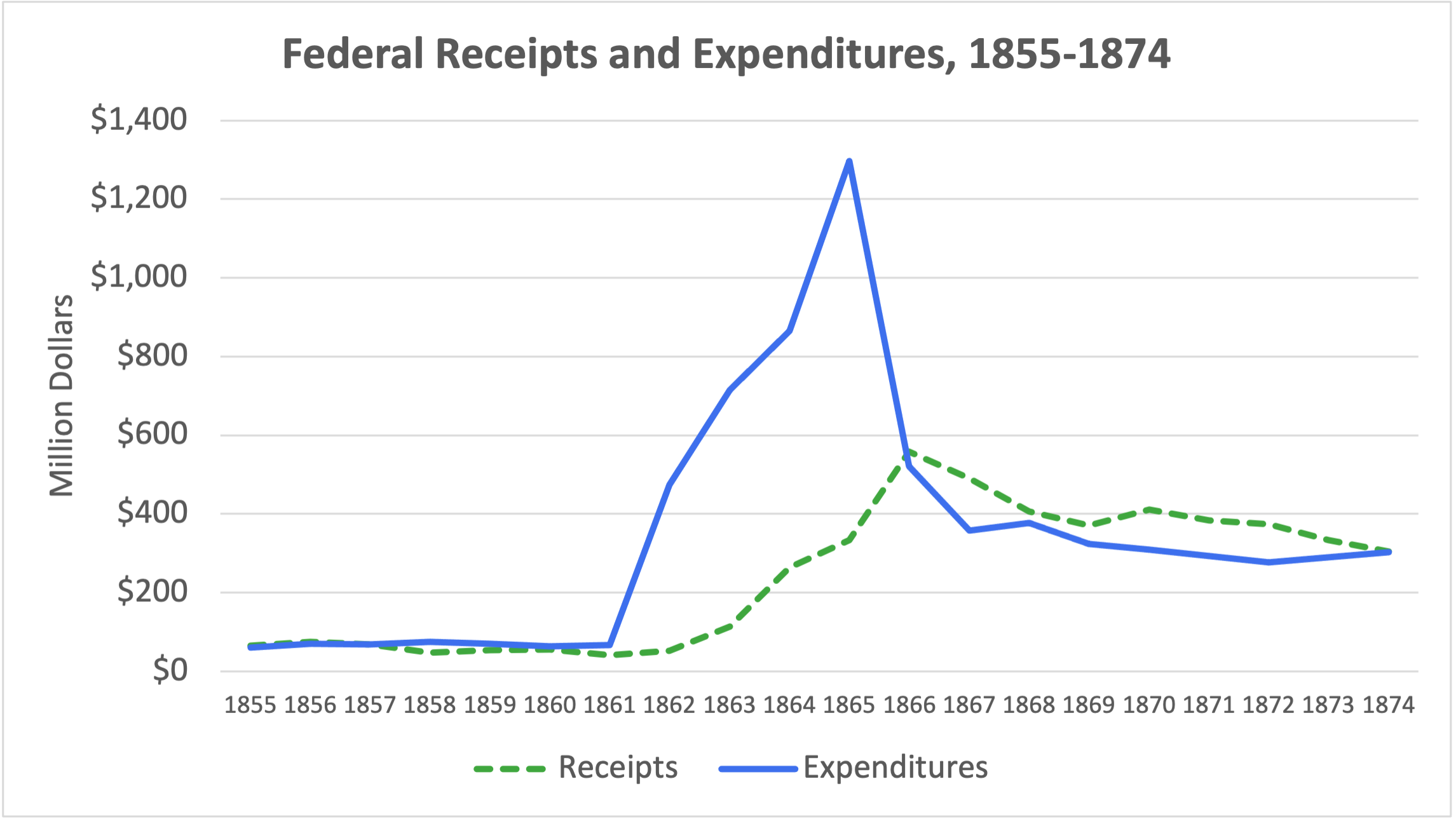

This centralized system worked fairly well until the Civil War forced the federal government to live far beyond its means. Federal outlays rose from $67 million in fiscal 1861 to $1.3 billion in 1865 (almost twenty-fold). Since most of that was deficit spending, the national debt rose from $90.6 million to $2.773 billion during that same time – an increase of almost 3000 percent in just five years.

That extra spending and debt represented frequent and ever-expanding appropriations acts, as well as new revenue-raising measures that attempted (and failed) to keep pace and a series of Congressionally-authorized bond issues, all of which had to go through the bottlenecks of the Ways and Means and Finance Committees. In the House, the Ways and Means chairman during the war was Thaddeus Stevens (R-PA) (who Tommy Lee Jones played in the movie Lincoln). Historian DeAlva Alexander wrote that the Ways and Means chairman was on the House floor managing tax and spending bills so often that he “became in fact as well as officially the ‘floor leader’, ranking in influence next to the Speaker. He arranged the order of business, indicated hours for adjournment, and fixed the time for closing the long sessions.”[2]

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Series Y 355-356.

Near the war’s end, on March 2, 1865, Rep. Samuel S. “Sunset” Cox (D-OH) rose to offer a resolution to split Ways and Means into three different committees. Ways and Means would retain taxes, tariffs and debt; a new Banking and Currency Committee would take issues pertaining to banks and paper money, and a new Appropriations Committee would take over all spending bills.

Cox, a renowned orator and florid writer (his nickname came about because as a young newspaperman, he once spent an entire page describing the beauty of a sunset), took pains to explain that his proposal was in no way a criticism of the Ways and Means membership, or of Stevens himself, only that the job was just too big for any single committee: “even an Olympian would faint and flag if the burden of Atlas is not relieved by the broad shoulders of Hercules.”[3]

Although some Ways and Means members spoke against the plan, it passed by a voice vote. In his definitive book on the subject, MIT political scientist Charles Stewart III concluded that:

…the creation of the Appropriations Committee embodied a balance between the perceived need for greater fiscal control and the aversion to concentrating institutional resources among a limited set of individuals. The technical problem of overwork was solved by bringing more people to the task; the political problem of institutional power was solved by dividing budgetary responsibility between two power centers.[4]

Without debate, the Senate followed suit two years later, creating a separate Committee on Appropriations (though Finance kept jurisdiction over banking and currency until 1913).

However, once decentralization had begun, the genie was tough to re-bottle.

The House Appropriations Committee retained exclusive jurisdiction over appropriations bills for just twelve years. In 1877, the House Commerce Committee, which had authorizing jurisdiction over Corps of Engineers water projects, began to report its own appropriations bills for those projects, and Commerce got around jurisdictional problems by moving the bills through the House under suspension of the rules (the pork-barrel nature of the bills ensured that the bills obtained the two-thirds vote margin necessary for suspension of all rules).

In response, the House Rules Committee proposed in 1879 to increase the suspension threshold from two-thirds to three-fourths. However, the Congressional Research Service notes that: “This move backfired. Not only did Commerce defeat this change in the rules, it secured passage of a substitute giving it ‘the same privilege to report a bill making appropriations for the improvement of rivers and harbors that is afforded to the Committee on Appropriations in reporting general appropriations bills.’”[5]

Rivers and Harbors was not considered a “general” (multi-department) annual appropriations bill, but other appropriations constituencies chafed to consolidate their authorizations and appropriations in one place. At the dawn of the 49th Congress in March 1885, the House Rules Committee (and thus, the majority leadership) agreed, recommending that Appropriations cede the Army, Navy, Military Academy, Indian, Agriculture, and Post Office appropriations bills to the authorizing committees. The Rules Committee report noted how big the bills had gotten since the Civil War and that Appropriations had, of late, been tardy in reporting the bills, and that “the distribution proposed will enable all these bills to be reported at earlier periods in the session, will permit a more careful and thorough consideration of each bill by the committee having jurisdiction of it, and also by the House, resulting in more considerate and economic legislation…”[6]

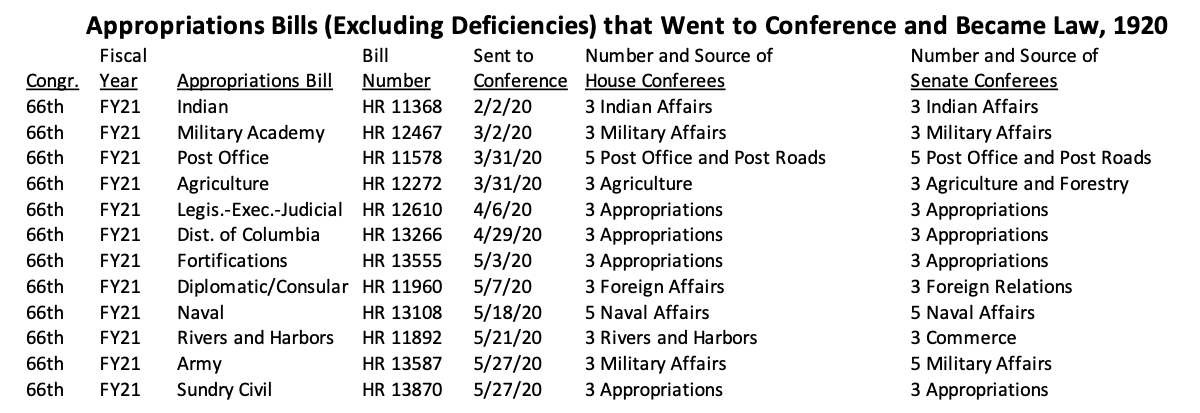

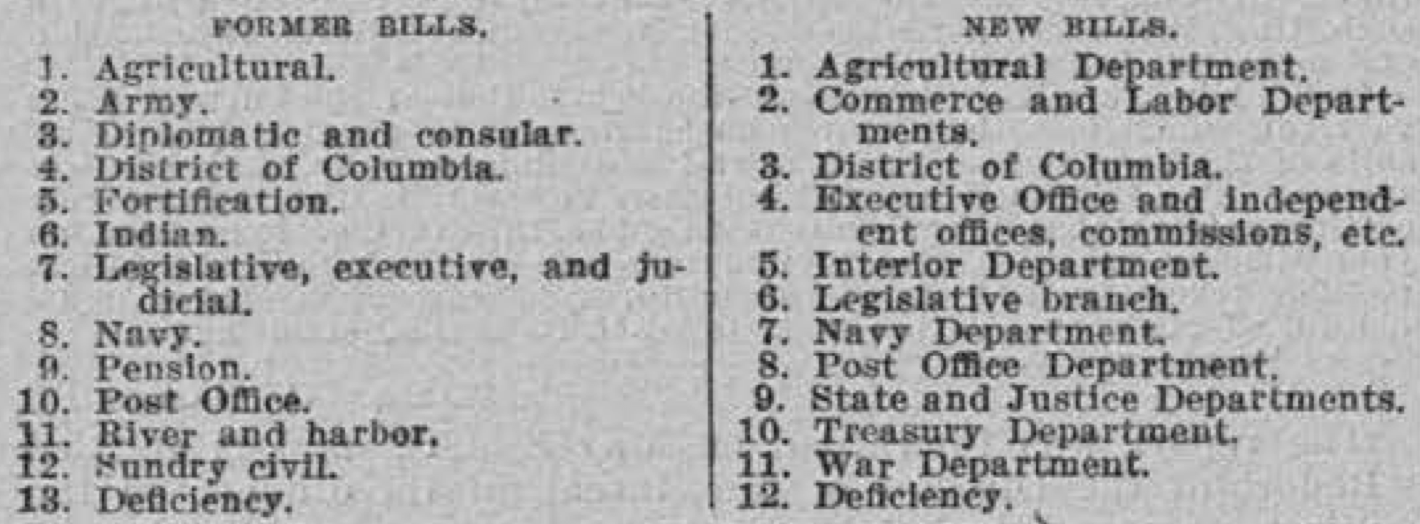

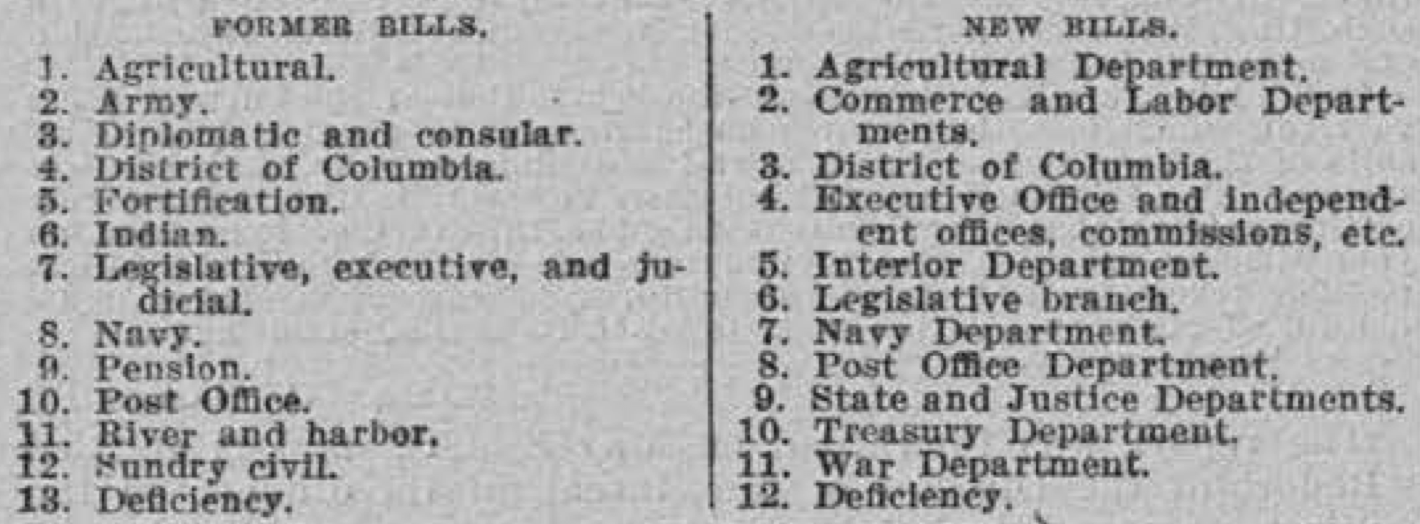

The House concurred, and the Senate followed suit in 1899, agreeing by unanimous consent to a resolution stripping its Appropriations Committee of jurisdiction over those same seven general appropriations bills (Rivers and Harbors was already gone) and giving them to the authorizing committees. By the end of World War I, this is what the jurisdiction looked like.[7]

Early highway funding

It was under this system that Congress took the first steps towards aiding the states in creation of good roads. In 1893, an appropriations bill reported from the Agriculture Committee created the Office of Road Inquiry within USDA to investigate better methods of road construction and management. This outreach and education program of the Agriculture Committees was supplemented by the Post Office and Post Roads Committees in their Post Office appropriations bill in 1912, giving the renamed Office of Public Roads its first construction appropriation for the improvement of selected post-roads.[8] That law also created within Congress a temporary Joint Committee on Federal Aid in the Construction of Post Roads to formulate a long-range roads policy.

The Joint Committee did not issue a final report until January 1915, and the report acknowledged great needs but did not put forth a detailed plan. The report did suggest that Congress try to thread a needle, creating a road program that was big enough and national in scope enough to avoid “a ‘pork barrel,’ from which the several States would receive annually a small contribution of funds distributed over a large mileage of roads and without producing the high class of public roads which are so much needed and desired,” but while still finding a way to “protect the several States in their right to control their local highway affairs against dictatorship from a Federal bureau in Washington.”[9]

The burgeoning public interest in good roads, combined with the confused jurisdictional situation, caused the House to create a separate and permanent Committee on Roads in June 1913. The new Roads panel had all authorizing jurisdiction over roads and post-roads but had no general appropriations bill of its own. In the Senate, however, authorizing jurisdiction over roads stayed with the Post Office and Post Roads Committee, which produced its own annual spending bill.

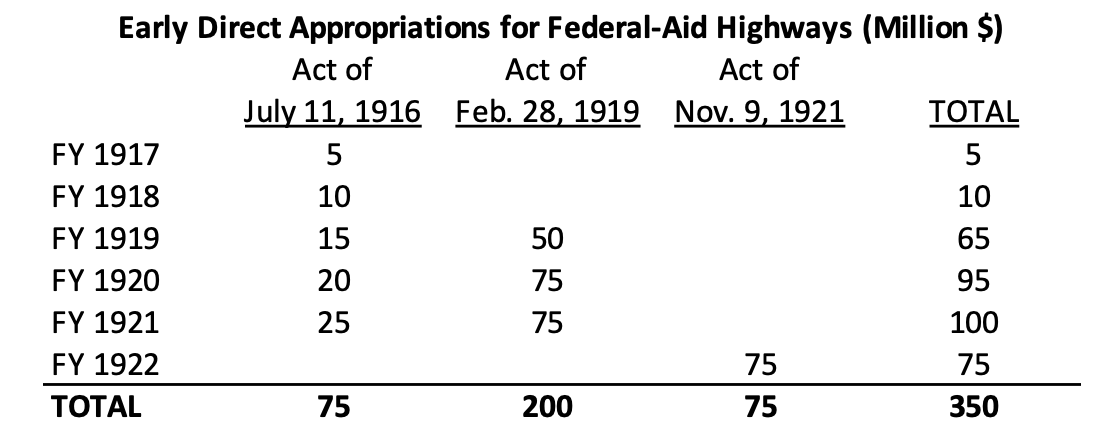

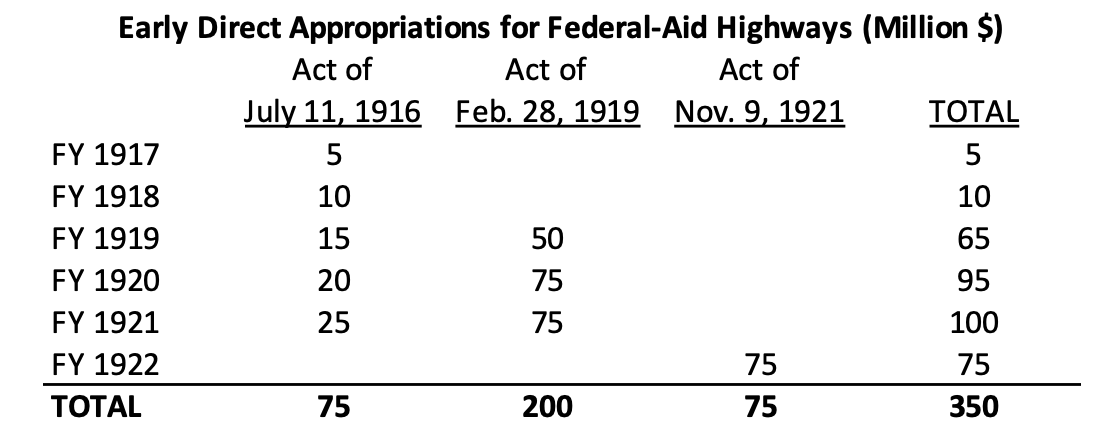

Together, the House Committee on Roads and the Senate Committee on Post Office and Post Roads drafted and passed the Federal Aid Road Act of July 11, 1916, which created the first system of federal road aid to states. The Act authorized USDA to “cooperate with the States, through their respective State highway departments, in the construction of rural post roads”.[10] Since House and Senate rules of the time did not prohibit authorizing committees from reporting their own special purpose appropriations (as opposed to multi-purpose “general” appropriations bills, which were restricted to the committees listed above), the Act contained its own appropriation – $75 million spread across fiscal years 1917-1921.

The Act also provided that each year’s appropriation would be apportioned to states by formula (one-third state area, one-third state population, and one-third state rural delivery route mileage). With the foundation of the Federal-aid highway program in place, things looked promising for the future of the roads program, with the roads committees in both chambers able to write their own combined authorization-appropriations bills.

Events, however, intervened.

World War I and recentralization

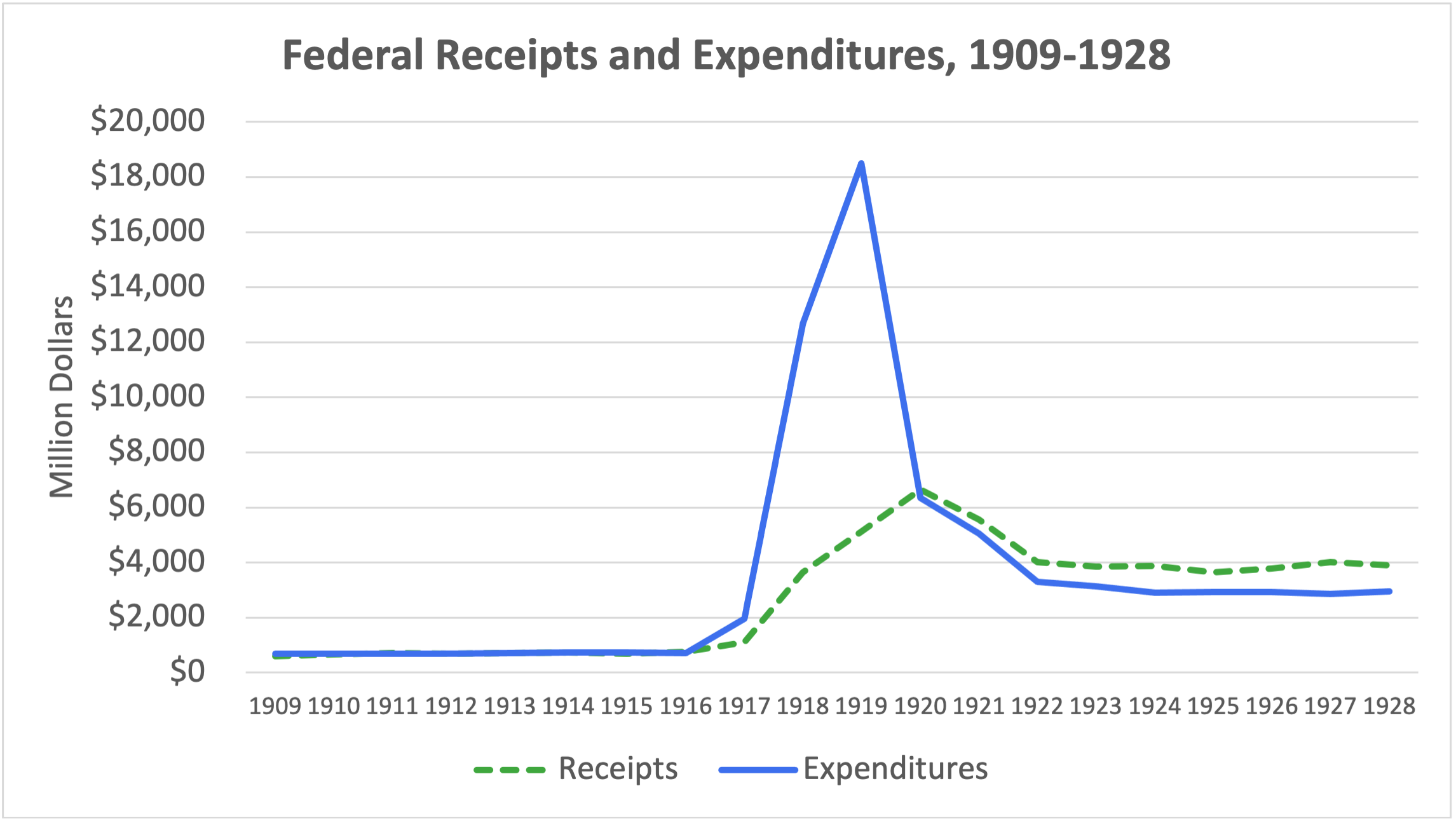

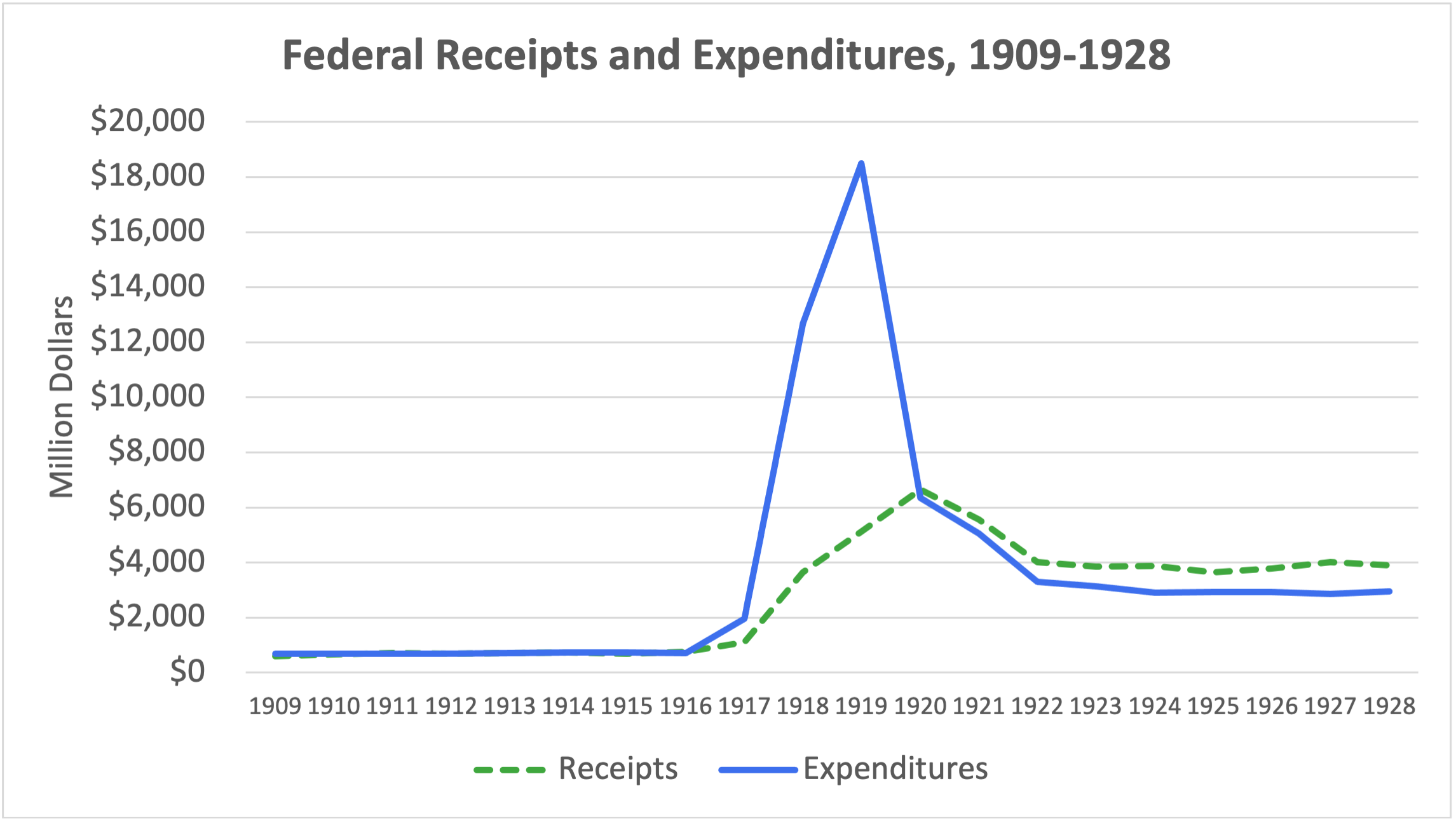

World War I had much the same effect on the federal government as the Civil War – massive increases in federal spending, taxes, and debt. Although the national debt only increased about sevenfold during the war, federal outlays rose from $734 million in FY 1916 to $18.5 billion in FY 1919 – an increase of about 2500 percent.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Series Y 355-356.

At this point, it was difficult for lawmakers to find paths to cut spending or raise revenues in an organized way. Traditionally, each Cabinet department submitted its annual appropriations requests to the Treasury Department, which then bound them up and submitted them to Congress without substantive change. The President’s control and coordination over spending requests depended on the quality of his relationships with his Cabinet.

President Taft created an independent commission in 1910 (the Commission on Economy and Efficiency, which became known as the “Taft Commission”), which recommended in its report that the President be given the power to submit a centralized budget.

Stewart reports that Taft issued an executive order in July 1912 requiring all departments to submit their appropriations requests to the White House for approval, but that the new Democratic Congressional majority instead passed an appropriations rider specifically forbidding the President from making any changes in the budget estimate submission process, and to submit estimates “only in the form and at the time now required by law, and in no other form and at no other time.”[11]

However, the fiscal consequences of the war changed some minds, and the postwar elections put the more deficit-conscious Republicans in charge of Congress once again. In 1919, the House and Senate each appointed a Special Committee on the Budget, and those panels promptly reported legislation[12] requiring the President to submit a consolidated budget for the entire federal government, creating a new Bureau of the Budget to help the President with this duty, and creating a General Accounting Office to help Congress and the President audit expenditures.

At the same time that Congress was looking at reforming the processes by which the executive branch made spending decisions, Congress also looked to reform itself. It had been obvious for years that the fragmentation of appropriations was having a negative effect on fiscal discipline. Historian George Galloway later wrote that because of this decentralization, “the House of Representatives lost an overall coordinated view of income and outgo and the several appropriation committees tended to become protagonists rather than critics of the fiscal needs of their departmental clientele.”[13]

The practical effects of the Senate fragmentation were similar to those in the House according to a recent history of the Senate Appropriations Committee: “Over the years, many legislators contended that such fragmentation of appropriations among numerous committees was in the end extravagant, with some describing the prevailing system as ‘illogical, unscientific and universally condemned by disinterested students of our Government.’”[14]

Political scientists David Brady and Mark Morgan did a study of two constituency-oriented appropriations bills (the Rivers and Harbors bill and the Agriculture bill) under both centralized and decentralized systems. They found that decentralization “resulted in higher increases in total budget outlays, higher increases in appropriations for rivers and harbors and agriculture independent of the government’s financial position, and clear indications of pork barrel politics in the rivers and harbors bills…When the House created a new set of monopoly committees based on special interests they expected a rise in expenditures; and, as we have seen, they got it.”[15]

Even before the war, the issue had been elevated to the point that in 1916, both the Democratic and Republican party platforms addressed the issue, with the Democrats explicitly calling for re-consolidation of appropriations inside the House Appropriations Committee, and the GOP platform endorsing by reference all of the Taft Commission recommendations, of which appropriations consolidation was a part.[16]

At the same time the House Special Committee on the Budget reported the budget bill, the panel also reported a resolution (H. Res. 324, 66th Congress) to amend House rules and consolidate all jurisdiction over general and special-purpose appropriations within the Appropriations Committee once again. The resolution also prohibited House conferees on non-appropriations bills from agreeing to Senate amendments making appropriations. Of the existing, fragmented system, the Committee report said that:

Without the adoption of this resolution true budgetary reform is impossible. Its adoption will permit Congress to treat appropriations in a businesslike and economical way. While it means the surrender by certain committees of jurisdiction which they now possess and will take from certain members on those committees certain powers now exercised, we ought to approach the consideration of the big problem with a determination to submerge personal ambition for the public good.[17]

(It should be noted that the Senate budget panel did not agree that appropriations consolidation was essential and did not report a resolution changing Senate rules to consolidate Senate jurisdiction).

The House and Senate passed the final conference report on the budget bill on May 29, 1920, sending the bill to the White House. Having finalized the centralization of spending authority in the executive branch, the House then turned to centralizing its own spending. H. Res. 324 was brought up on June 1, 1920. Rather than cast an “anti-reform” vote, opponents of the centralization plan instead chose to contest the vote on the special rule (H. Res. 527, 66th Congress) allowing the consolidation plan to be brought up for a vote. The rule passed by a narrow margin of 158 to 154. Richard Fenno, in his magisterial book on the House Appropriations Committee, later did a numerical breakdown, noting that 64 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans voted for the rule, and while the 15 members of Appropriations were unanimously in favor of the rule, the members of the seven panels that would lose spending jurisdiction voted, 67 to 38, against the rule.[18]

The underlying resolution consolidating appropriations jurisdiction passed by a 200 to 117 vote. The plan had clearly been carried to victory by the idea that in-house consolidation was part of a package with executive branch consolidation, which had already been sent to the White House.

But meanwhile, Woodrow Wilson stunned Congress by vetoing the budget bill on June 4, 1920, because he wanted the ability to fire the Comptroller General. Congress failed to override the veto by a 178 to 103 margin, ten votes short of two-thirds. A nearly identical bill was sent to President Harding the following year, and the Budget and Accounting Act became law on June 10, 1921.

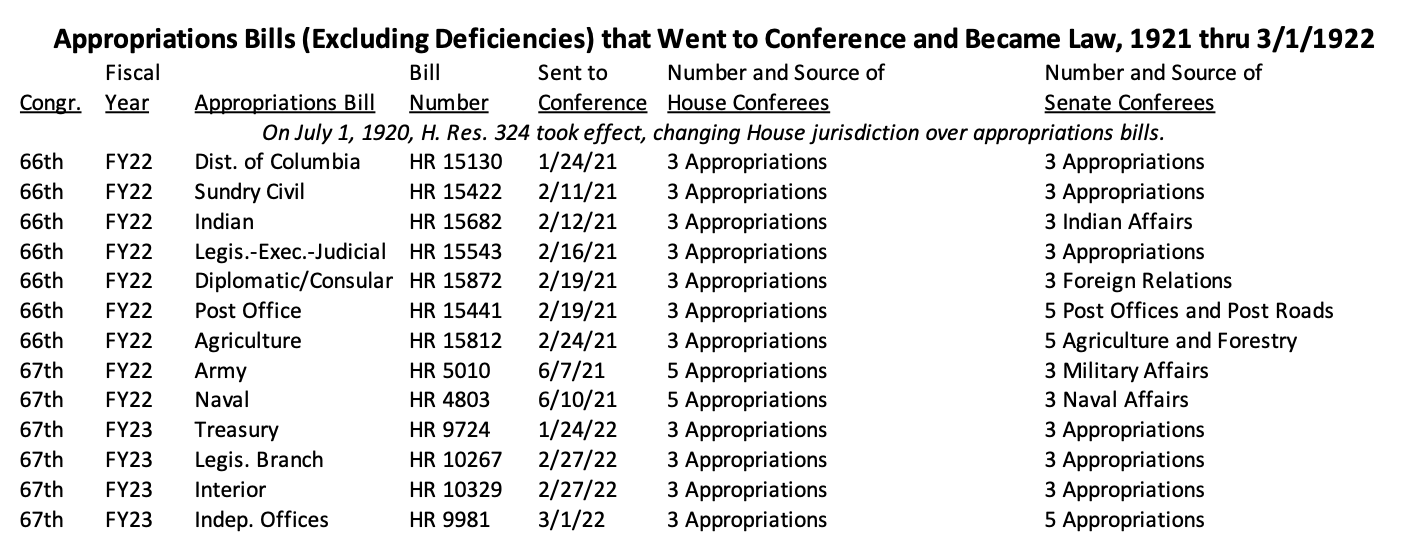

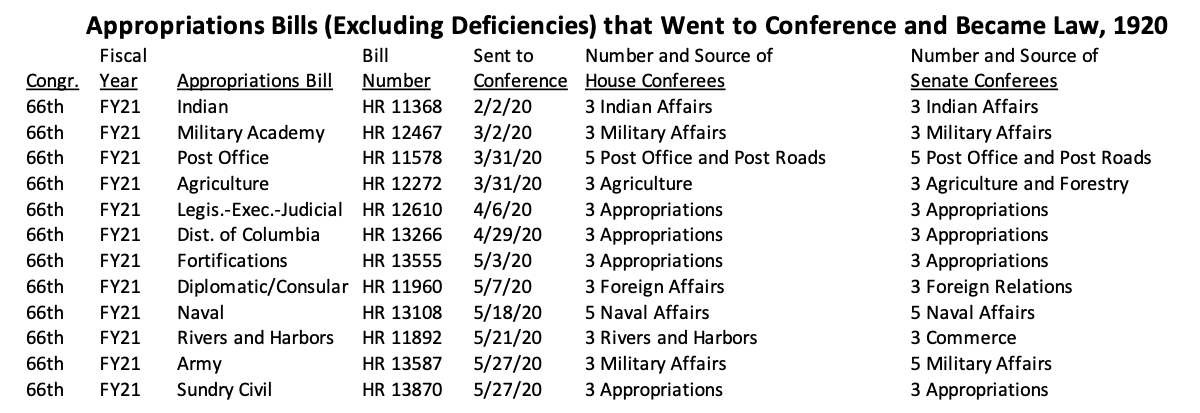

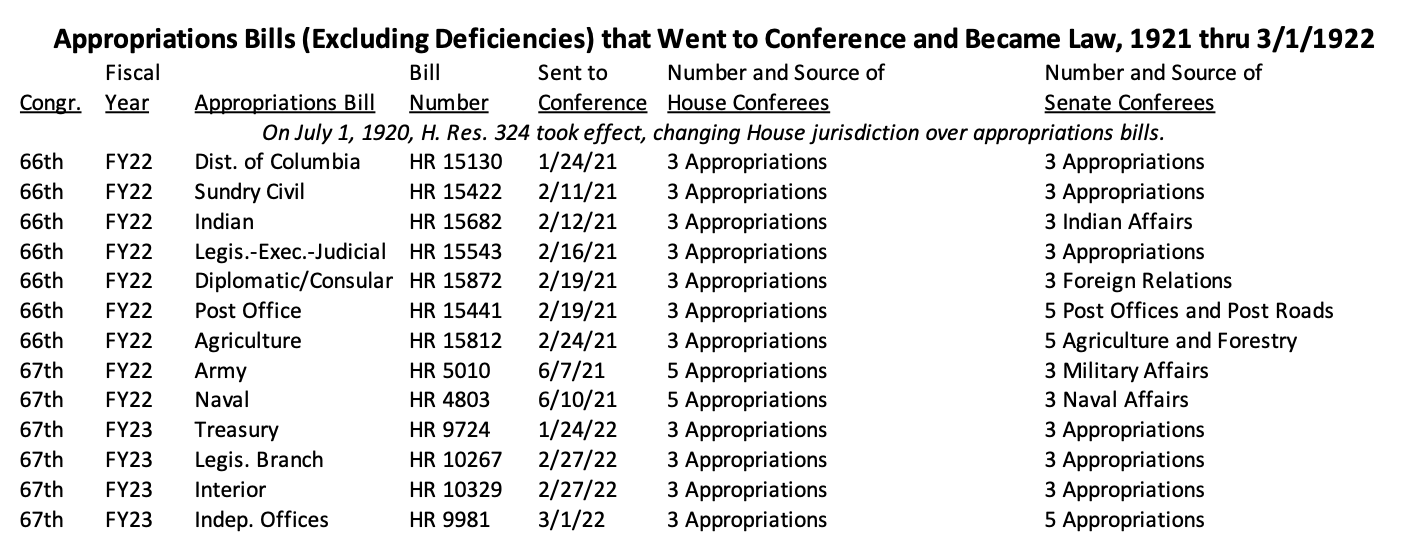

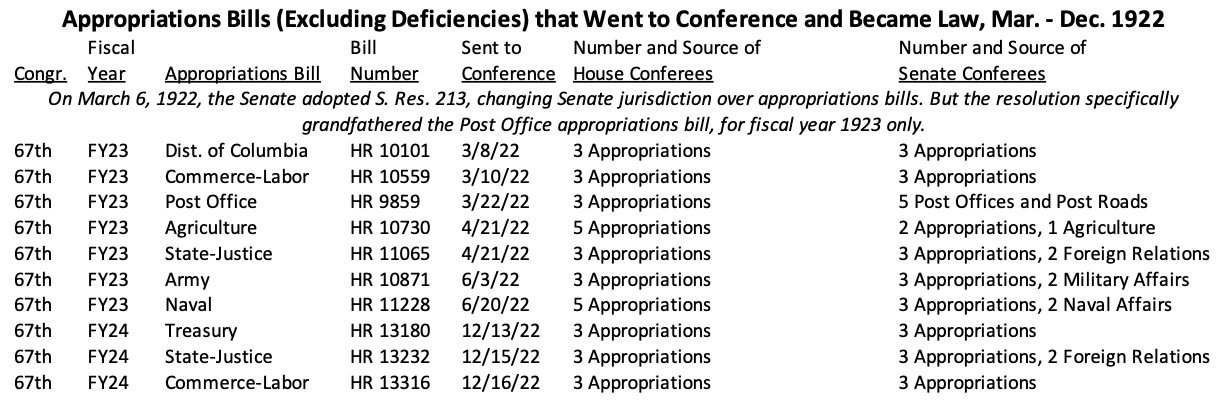

But, in the meantime, there was no centralized budget, and there was only centralized jurisdiction over appropriations in one chamber, which led to some odd conference committee lineups in 1921 and early 1922.

The 1921 highway bill

While all this was going on, the original five-year, $75 million appropriation from the 1916 Act had been supplemented in 1919 with an additional $200 million for the Federal-aid program over fiscal years 1919-1921,[19] with the additional appropriations justified by the wear and tear that the war’s logistical demands had put on state roads. But the new appropriation, like the old, was due to expire on June 30, 1921.

The impending lapse in funding was felt before the start of the fiscal year, due to the practice of the Bureau of Public Roads of issuing certificates of apportionment to states on January 1 of each year for each state’s share of the appropriated funds that would then be released to the states for obligation on the start of the fiscal year on July 1. The Chief of the Bureau of Public Roads later said, “The fact that a new apportionment of funds was not made in January 1921 made it impossible for the States to maintain an unbroken continuity of policy and administration in respect to Federal-aid work, and this condition has resulted in an unprecedented number if withdrawals, cancellations, and modifications of existing projects as the States have endeavored to adjust their programs to a reduced rate of expenditure.”[20]

The third and final session of the 66th Congress ran from December 6, 1920 to the constitutional end of the Congress at noon on March 3, 2021. The House Roads Committee tried to answer the states’ cry for more highway funding, moving a bill (H.R. 15873, 66th Congress) to the House floor under suspension of the rules on February 7. The bill authorized, but did not appropriate, an additional $100 million for the road program for fiscal 1923. However, because the bill also extended the expiration deadline for previous appropriations, it was considered to be an appropriations measure and thus in violation of the new centralization rule – except for the fact that it was being considered under a motion to suspend all House rules, including the newest one. The motion passed by a vote of 278 to 58 (83 percent in favor, more than the two-thirds needed).

With the March 3 expiration of the Congress approaching, the Senate was debating the fiscal 2022 Post Office appropriations bill on February 17 when Sen. Claude Swanson (D-VA) proposed to add the House-passed road authorization bill as an amendment to the appropriations bill. Since this would have violated the no-legislation-on-appropriations point of order, Swanson made his amendment in the form of a motion to suspend the rules, again needing a two-thirds margin.

After a full day’s debate (during which the chairman of the Post Office and Post Roads Committee asked that his committee be given time to write its own bill), the Senate on February 18 failed to approve the motion to suspend the rules, 42 to 33 (56 percent, short of two-thirds). Nothing else happened before the 66th Congress ended on March 3.

During the next (67th) Congress, after long negotiation, the House and Senate roads committees responded with the Federal Highway Act, signed into law on November 9, 1921. The Act created the modern highway program, requiring each state to designate up to seven percent of its total highway mileage as part of the Federal-aid system and requiring the states to split their systems between primary, or interstate, highways and secondary, or intercounty, highways. States would receive apportionment of appropriations under the formula set by the 1916 Act except that each state was given a one-half of one percent minimum apportionment.

However, the 1921 Act only contained one year’s worth of appropriations for the program – $75 million for fiscal 1922. (This did not violate the new House rules because, seeing a conflict coming in a conference between a non-appropriating House committee and an appropriating Senate committee, the House voted in advance to approve a special resolution giving the Committee on Roads one-time-only authority to agree to an appropriation in the road bill during conference negotiations with the Senate.[21])

The $75 million appropriation for 2022 was also made four months into the fiscal year, well after all of the appropriations bills had been settled and when Congress had begun to look to the fiscal 1923 budget cycle. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon wrote to President Harding on November 4 about the pending legislation, advising him to tell Congress that “if Congress desires this large additional expenditure to be made as well as the $100,000,000 for which provision has already been made, sufficient additional taxes should be provided for the purpose. It will be difficult indeed to establish the Budget System on a firm basis if Congress is to authorize new expenditures which have not been taken into account in the Budget…”[22]

Harding wrote back to Secretary Mellon on November 7 that “I quite agree with you that when Congress undertakes to add so large an appropriation to the budget essentially prepared it ought to take the responsibility of providing for the additional funds which it appropriates.”[23] But Harding signed the highway bill into law, despite this objection, the following day.

The special authority given to the House Roads panel to agree to an appropriation on their authorization bill in conference was only good for that one bill. Subsequent appropriations for the road program were uncertain.

The first budget

On December 6, 1921, President Harding transmitted to Congress the first centralized federal budget under the terms of the new law (for fiscal 1923). For the first time, all of the appropriations requests were matched with federal revenue and expenditure (outlay) tables. The budget called for federal receipts of $3.338 billion and expenditures of $3.506 billion in fiscal 1923.

The FY 1923 budget was a landmark piece of work in many ways. Prepared by future Nobel laureate (and Vice President of the U.S.) Charles Dawes, the first budget director, the budget brought a typically Republican approach to federal spending, viewing the government as a corporation, the President as CEO, the Cabinet as executive vice presidents, and taxpayers as shareholders.

That first budget contained much that is still with us, including object classification schedules, a division of all accounts by fund type (general, loan, trust or revolving), functional category classification, and circular #11, which told agencies how to fill out their budget request forms.

The budget also proposed to restructure the annual appropriations bills, away from the structure that had slowly evolved along functional lines over more than a century into one that was based around Cabinet Departments having all of their expenses in one bill. Congress went along with the plan, with House Appropriations chairman Martin Madden (R-IL) noting that, under the old structure, some departments were dependent on as many as five separate appropriations bills per year. Madden submitted this summary table in the Record on June 30, 1922:

At this point, the postal committees had been supplying the grant funding for the road program itself ($75 million per year), while the annual Agriculture appropriations bill had been providing an additional $600 thousand per year or so for the salaries and expenses of the Bureau of Public Roads (aside from the 3 percent takedown from the road formula aid for administrative expenses). Any move towards a new appropriation structure solely based on departmental boundaries was going to strengthen whoever wrote the annual Agriculture funding bill and weaken the postal committees further.

But most of all, that first centralized budget shifted the focus away from appropriation amounts and toward expenditure (outlay) amounts, with an emphasis on the deficit – or what the budget termed “the one great important question, to wit, the relation of the money actually to be spent by the Government to the money actually to be received by the Government in any given year…”[24] The budget criticized the existing practice of appropriating all the money for a multi-year project at once:

…if [Congress] will pass the budget providing simply for the amount actually to be expended during the fiscal year, with Executive pressure now being exerted to keep the departments within the limit of this expenditure, a continuance of the method will automatically largely eliminate the indefinite cash demands made in the past by departments on account of unexpended balances in addition to their current appropriations.

A system by which requests for appropriations are based on the actual need of money for disbursement during the fiscal year for which the appropriation is made will thus tend to prevent hereafter the wide, indefinite and fluctuating margin between the expenditures for a given year and the appropriations requested of Congress to cover the same period.[25]

The budget specifically addressed capital-intensive multi-year contractual accounts like the highway program:

The fact that contracts are let by the Government which, of necessity, can not be completed within the fiscal year during which they are let does not imply the necessity of immediately making available to the contracting department the entire sum of money eventually to be expended on the contract. While in many instances the amount appropriated has been only that which could properly be expended during the year for which the appropriation was made, there have been other instances in which the total amount called for by the project was appropriated at one time, without regard to the need for the expenditure during the current year. No properly organized private corporation would handle its business this way.[26]

It was in this environment that the need for more appropriations for the highway program for fiscal 1923 was considered.

The budget assumed $105 million in FY 1922 expenditures and $125.7 million in FY 1923 expenditures for the Federal-aid highway program under the terms of the law signed the previous month.

$125.7 million, in context, was quite a lot of money – the combined projected 1923 outlays for the legislative branch, the federal judiciary, the executive office, the rest of the Agriculture Department, and the Departments of State, Commerce, Labor, and Judiciary were only $119 million.

However, that $125.7 million was all spending that was anticipated to be made from the unexpended balances of prior appropriations for the road program. The budget requested no additional appropriations for the program in fiscal 1923.

The FY 1923 appropriations process

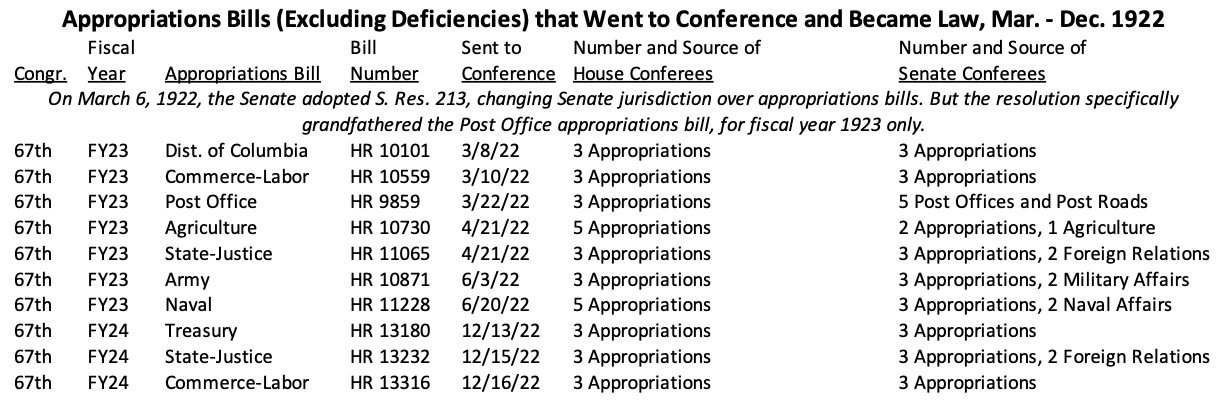

While the road program faced fiscal uncertainty, the rest of the government went about its business. In January 1922, the House Appropriations Committee reported, and the House passed, a fiscal 1923 appropriations bill for the Post Office (H.R. 9859, 67th Congress). The House-passed bill made no mention of roads, but it was referred to the Senate Committee on Post Office and Post Roads.

Meanwhile, the Senate had been wrestling with the idea of following the House and recentralizing appropriations jurisdiction within the Appropriations Committee. Appropriations chairman Francis Warren (R-WY) introduced a resolution on January 18, 1922 (S. Res, 213, 67th Congress) to amend Senate rules to bring this about. Warren noted that the FY 1923 budget called for a wholesale reorganization of the annual appropriations bills that would make the Senate jurisdictional lineup unworkable, and that the House Appropriations Committee was going along with the plan.[27]

Warren asked for his resolution to be referred to the Senate Rules Committee, and suggested a course of action for Rules: “there could be drawn and added to the main committee members from the other committees, experienced in appropriations, thus enlarging to some extent the general Appropriations Committee…if not as permanent members, then surely as ex officio members.”[28]

The Rules Committee was listening, and when the resolution was reported in March 1922 it matched the House rule for centralization of appropriations but also provided that two members of each of the committees set to lose jurisdiction over an appropriations bill would be made ex officio members of Appropriations for consideration of that bill. After much debate and a series of amendments (one of which required that one of the ex officio members be named to any House-Senate conference committee on their bill), the Senate passed S. Res. 213 on March 6, 1922 by a vote of 63 to 14.

However, the resolution passed by the Senate grandfathered one, and only one, bill:

Provided, That this rule shall not apply to the bill making appropriations for the Post Office Department for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1923.[29]

In essence, the members of the Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee were being given one last chance to work their will on both highway policy and funding before ceding control over the funding side of the equation to Appropriations. It was the last time that appropriators in one chamber conferenced a bill with all non-appropriators from the other chamber. (The practice of certain authorizing committee members holding ex officio status on Senate Appropriations, remarkably, stayed intact until the Stevenson Committee got rid of it in the 1977 reforms.)

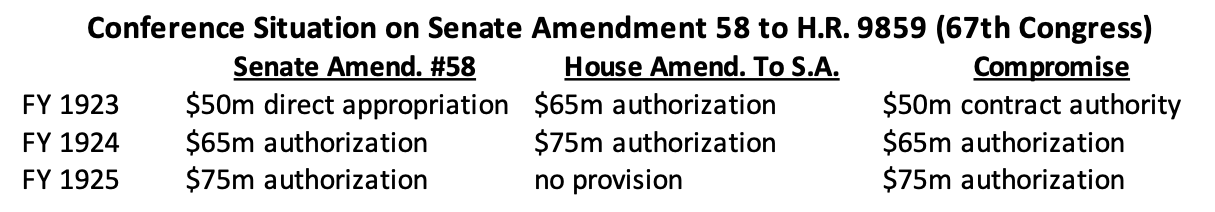

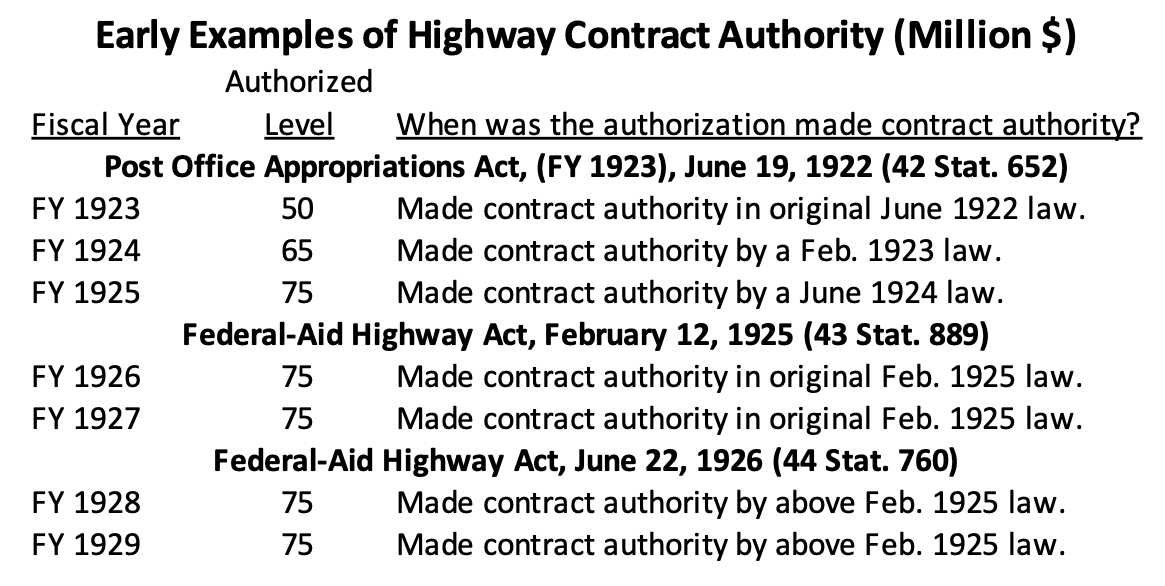

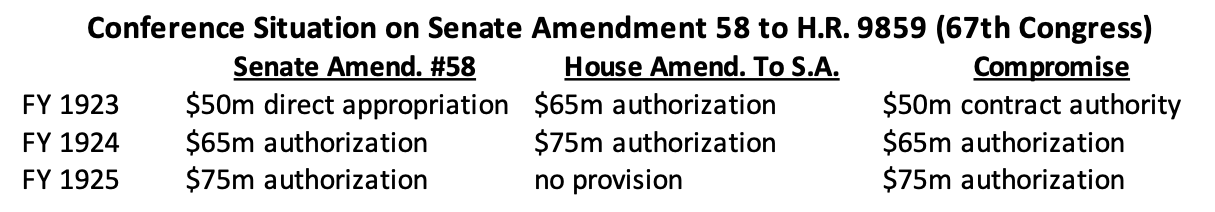

One week after the Senate agreed to S. Res. 213, the Post Office and Post Roads Committee reported the grandfathered Post Office appropriations bill (H.R. 9859, 67th Congress). One of the amendments recommended by the committee to H.R. 9859 added a section 6 to the bill appropriating $50 million for the Federal-aid highway program for FY 1923 and authorizing (but not appropriating) an additional $65 million in 1924 and $75 million in 1925. The Senate agreed to the amendment and to the amended bill by voice vote on March 20.

In April, conferees on H.R. 9859 were appointed from the House Appropriations Committee and the Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee. The House conferees were presented with two problems. First, the House Post Office Appropriations Subcommittee did not have jurisdiction over the Agriculture Department’s Bureau of Public Roads appropriation. Second, the authorization portion of the Senate amendment constituted legislation on an appropriations bill in violation of the new rules, meaning that House conferees were not free to agree to the amendment in the body of the conference report.

An initial conference report was filed on May 8, 1922 which left amendment number 58 (section 6 of the Senate bill) in true disagreement. The Senate agreed to the conference report that day and the House agreed to the report on May 13. At that time, the House concurred to Senate amendment 58 with an amendment consisting of the entire text of a highway authorization bill (H.R. 11131, 67th Congress) reported from the Committee on Roads and which had passed the House on May 1 by a 240 to 31 margin .

That House bill/amendment contained funding authorizations only (no appropriations) of $65 million in 1923 and $75 million in 1924, and also contained controversial language capping Federal-aid project costs at $12,500 per mile. The House then agreed to a second conference on amendment 58 and other amendments remaining in disagreement and appointed the same conferees, with the Senate following suit on May 27. A second conference report (H. Rept. 1065, 67th Congress) was filed on June 3.

Contract authority

Sometime between the House vote on May 13 and the filing of the second conference report on June 3, contract authority was born. In lieu of the Senate appropriation-authorization amendment and the House’s authorization-only amendment to that amendment, the conference report recommended compromise language. The final bill would contain federal-aid road authorizations only – $50 million in 1923, $65 million in 1924 and $75 million in 1925 (no direct appropriations). However, the conference report contained new and unprecedented language pertaining to the $50 million authorization for FY 1923:

The Secretary of Agriculture is hereby authorized, immediately upon the passage of this Act, to apportion the $50,000,000 herein authorized to be appropriated for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1923, among the several States as provided in section 21 of the Federal Highway Act approved November 9, 1921: Provided, That the Secretary of Agriculture shall act upon projects submitted to him under his apportionment of this authorization and his approval of any such project shall be deemed a contractual obligation of the Federal Government for the payment of its proportional contribution thereto.[30]

Conferees from an appropriations-only committee and an authorizing committee whose ability to originate appropriations was being taken away, sent to resolve differences between language making an appropriation and language making a simple authorization, found a way to split the baby successfully – by creating an authorization that behaved like an appropriation, making the government responsible for commitments made under the authorization, in advance of any appropriation.

During House debate on the conference report on June 6, the strategy was explained. House Majority Leader Frank Mondell (R-WY) said:

In the Senate certain appropriations were made for carrying on road work. The conferees on the part of the House were naturally and properly anxious to eliminate from the Post Office bill a direct appropriation for public roads. Such appropriations should not be carried on a Post Office appropriation bill. At the same time the conferees were anxious to carry out the will of the House in making sufficient and abundant provision for carrying on road work. Certain of the Senate conferees were not entirely willing to trust the Congress to make the deficiency appropriation, as might be necessary if nothing but an authorization were left in the bill with no definite provision under which road funds would unquestioningly be available.[31]

Rep. (and future longtime Sen.) Carl Hayden (D-AZ) questioned Mondell:

Mr. HAYDEN. I want to get the idea correctly in my head. This bill authorizes the good roads office to create a deficiency that Congress will meet?

Mr. MONDELL. That is what it amounts to. There is no difference of opinion in regard to carrying out the road program.[32]

The chairman of the House Post Office Appropriations Subcommittee, C. Bascom Slemp (R-VA), amplified:

It was felt that under these circumstances contracts can be made and appropriations be made by Congress in accordance with the need. In that way we will prevent the piling up of a large amount of money in the Treasury that cannot be used…

…The fiscal year will be at an end in 30 days and while the appropriation committee did not have any desire to have this thrust upon them, because it is legislation, it was the simplest way out of it.[33]

The binding nature of the new contract authority was made clear during the debate during a colloquy between Chairman Slemp and Rep. William Stafford (R-WI):

Mr. STAFFORD. I notice for the first time in the history of road legislation that the conferees have bound the Government in the form of a contract to carry out the amount that would be apportioned of the $50,000,000 authorization for expenditures in the next fiscal year.

Mr. SLEMP. Yes.

Mr. STAFFORD. What is the reason why by legislation we should make a contractual obligation to carry out the apportionment fixed by the Department of Agriculture?

Mr. SLEMP. As far as I could get the thought, it is this: The authorization passed by Congress would carry necessarily an obligation on the part of Congress, certainly moral, at least, to carry out the proposition in accordance with the amount authorized…It has been represented that contractors might not know for sure whether they could make the contracts under these circumstances, and we felt this provision placed in there would make it absolutely sure.

Mr. STAFFORD. This applies only for the year 1923?

Mr. SLEMP. Yes.

Mr. STAFFORD. And as the chairman of the committee, the gentleman from Illinois (Mr. MADDEN) just stated, it should be made a permanent policy. If that is so, there is no need for an authorization. You might as well appropriate the money at the beginning.[34]

The ranking minority member on the Post Office Appropriations subcommittee, Thomas Sisson (D-GA), made clear that the extra $50 million for FY 1923 was necessary because, while most states had more unexpended apportionment balances than they needed for the upcoming year, fourteen fast-spending states were out of money and would have no new program in 1923 without new apportionments.[35]

Appropriations chairman Martin Madden (R-IL) closed the debate by saying:

[The bill] authorizes an appropriation of $50,000,000. It authorizes the Secretary of Agriculture to enter into contract obligations with the States to up to the amount of their allotments. It authorizes the States to enter into contracts with people who are going to build their roads. It binds the Congress of the United States to make the appropriations of the money as needed. What more is there to be done?[36]

The House agreed to the conference report by a 211 to 26 vote. The next day, on June 7, the Senate agreed to the conference report by voice vote without debate. The bill was signed into law by President Harding on June 19, 1922.[37]

Epilogue

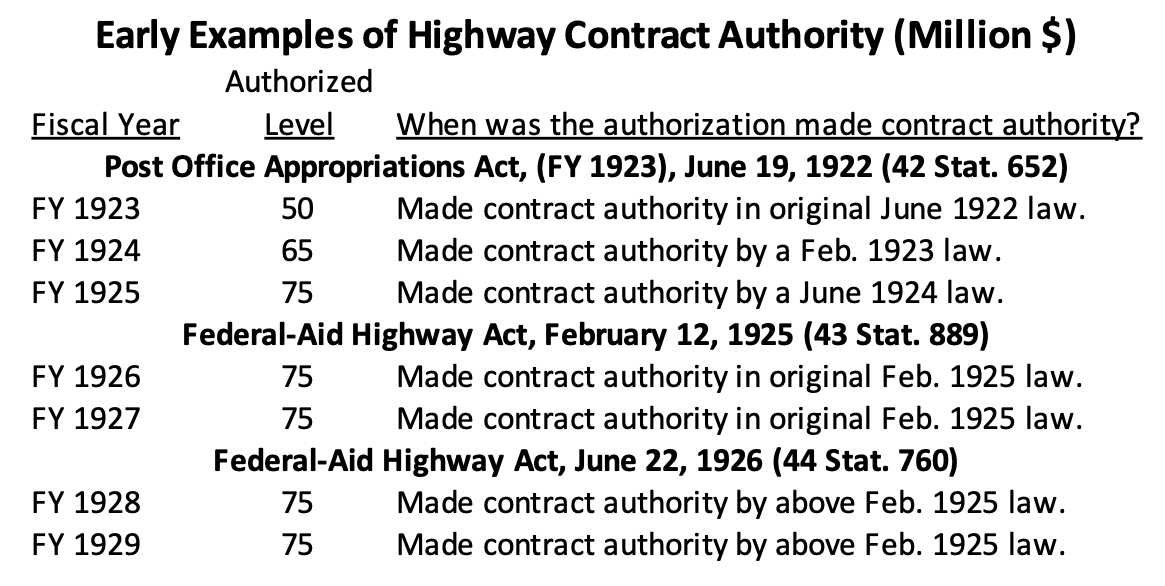

As Rep. Stafford pointed out during the debate, only the FY 1923 authorization in the Post Office bill was legally binding “contract authority.” The FY 1924 and 1925 authorizations, as originally enacted, were simply authorizations – permission slips for future appropriations.

If the members of the Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee thought that, by gaining ex officio status on Appropriations for the consideration of the annual Post Office appropriations bill, they would also keep some influence over public roads appropriations, they were mistaken. As had been the case since 1912, the annual appropriation for Bureau of Public Roads salaries and expenses came from the Agriculture bill, not the Post Office bill, since USDA is where the Bureau was located. And it was this appropriations subcommittee, devoid of Post Office Committee representation, that would handle funding for the program in the future.

The FY 1924 Agriculture Appropriations Act, enacted on February 26, 1923, deemed the preexisting $65 million authorization for FY 1924 to be a contractual obligation of the federal government, and the FY 1925 Agriculture spending bill did the same for the $75 million FY 1925 authorization. The next authorization bill, enacted on February 12, 1925, authorized $75 million per year for FY 1926 and 1927 for the highway program, and designated both years’ authorizations to be contract authority along with any apportionments “which may hereafter be authorized” – making all future highway authorizations contract authority as well.[38]

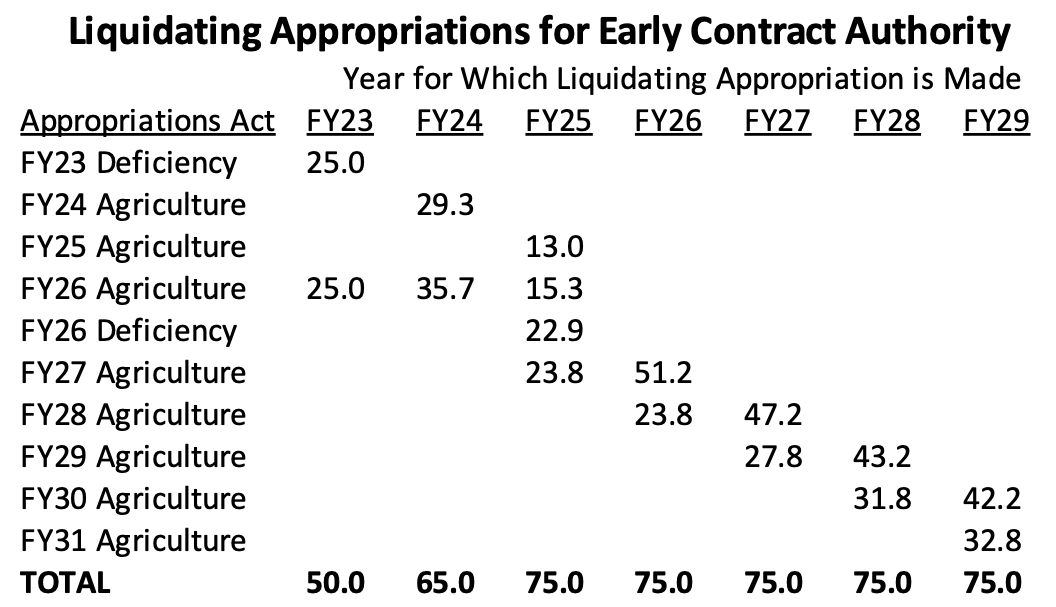

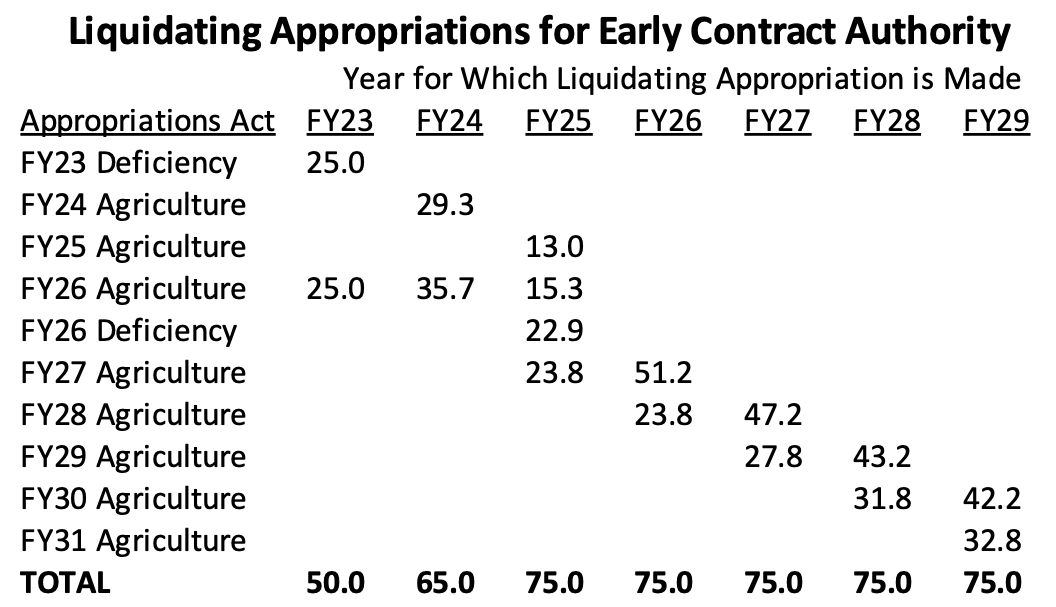

The contracts issued pursuant to the original $50 million of FY 1923 contract authority were paid off, or “liquidated,” by subsequent appropriations in two parts – half in a FY 1923 deficiency appropriations bill, and half in the FY 1926 Agriculture Appropriations Act. Liquidating appropriations in the early days would specify which year’s authorizations they were redeeming – for example, the $76 million appropriation provided in the FY 1926 Agriculture appropriations bill for the highway program was allocated in the bill text as follows:

$25,000,000, the remainder of the sum of $50,000,000 authorized to be appropriated for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1923; $35,700,000, the remainder of the sum of $65,000,000 authorized to be appropriated for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1924; and $15,300,000, being part of the sum of $75,000,000 authorized to be appropriated for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1925…[39]

The table below shows how the switch from direct appropriations to contract authority was able to postpone the recording of tens of millions of dollars per year in inevitable appropriations into subsequent budget years.

The phrase “contractual obligation” did not appear in the Statutes at Large in the five years preceding the FY 1923 Post Office Appropriations Act, but in the subsequent five years, it appeared repeatedly – not just for the highway program, but starting in 1925, contract authority began popping up all over the place:

- $1.125 million in contract authority for the Agriculture Department to buy land for the Upper Mississippi Wild Life and Fish Refuge (43 Stat. 842)

- $2.15 million in contract authority for the Army Air Service to buy new airplanes and parts (43 Stat. 908)

- $1 million in contract authority for the National Park Service to build additional roads and trails (43 Stat. 1179)

- $500 thousand in contract authority for the Interior Department for helium production (44 Stat. 104)

- $600 thousand in contract authority for the George Rogers Clark Sesquicentennial Commission (44 Stat. 888)

- $50 thousand in contract authority for the Bear River migratory-bird refuge (44 Stat. 895)

- $150 thousand in contract authority for the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission (44 Stat. 1627)

Interestingly, in all of those cases, it was the Appropriations Committees, not any authorizing committees, who created the contract authority.

The legally binding nature of contract authority was recognized over the decades by various courts and by the U.S. Comptroller General, who summed up the possible consequences of failure to provide liquidating appropriations: “the United States is obligated to pay under contracts where Government officials were statutorily authorized to enter into contracts in excess of or in advance of appropriations…While no one can force the Congress to appropriate liquidating monies, (B-203841, March 30, 1955) the States could sue the United States in Federal Court to enforce its right to be paid under the Act. Any award to the States would then be paid from the permanent judgment appropriation.[40]

The “permanent judgment appropriation” (31 U.S.C. §1304) is a provision of law that automatically appropriates such sums as necessary from the U.S. Treasury to pay off court judgments against the federal government. In other words, if the Appropriations Committees fail to provide sufficient appropriations to liquidate contract authority, they won’t necessarily be saving the Treasury any money, as the states could simply go to court and get the money that way.

The Supreme Court summarized contract authority in this way:

…there are authorizations for future appropriations, but also initial and continuing authority in the Executive Branch contractually to commit funds of the United States up to the amount of the authorization. The expectation is that appropriations will be automatically forthcoming to meet these contractual commitments. This mechanism considerably reduces whatever discretion Congress might have exercised in the course of making annual appropriations.[41]

Takeaways

- The creation of contract authority was a direct response to, and pushback against, the budget centralization of 1919-1922. The nascent highway stakeholder groups, which already included all 48 state governments and the “good roads movement,” had grown accustomed getting their funding directly from the House and Senate roads committees. Contract authority allowed the roads committees to keep funding the highway program directly, when everyone else had been forced to get annual appropriations from the Appropriations Committees.

- The creation of contract authority satisfied the Harding Administration’s desire for better year-to-year cash management of outlays. By waiting to provide liquidating appropriations until the Bureau of Public Roads believed they would actually be needed, the Bureau of the Budget felt that the new deficit estimates in the new centralized Budget would be more accurate.

- The creation of contract authority was, in some ways, a happy accident. If the Senate and House had not been a year apart in the transition to centralized appropriations jurisdiction, and the House Appropriations Committee and the Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee not split jurisdiction over postal appropriations for 1923, it is not certain what would have happened. The issue probably would not have been settled in the postal appropriations bill. Could the postal committees have successfully created it on their own, in a stand-alone authorization bill, against what probably would have been strong opposition from Appropriations? We will never know…

[1] See Louis Fisher, Presidential Spending Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975) generally, and especially chapter 10 on “Executive Commitments”

[2] DeAlva Stanwood Alexander, History and Procedure of the House of Representatives (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1916), p. 234.

[3] Congressional Globe, 38th Congress, 2nd session, March 2, 1865, p. 1312.

[4] Charles Stewart III, Budget Reform Politics: The Design of the Appropriations Process in the House of Representatives, 1865-1921 (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 1989) p. 83.

[5] Congressional Research Service, History of the United States House of Representatives, 1789-1994 (Washington: GPO, 1994 – H. Doc. 103-324), pp. 213-214.

[6] Congressional Record (bound edition), December 14, 1885 p. 170.

[7] House Report No. 373, 66th Congress, 1st Session, p. 4.

[8] Federal Highway Administration. America’s Highways 1776-1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program (Washington: GPO, 1976) p. 81.

[9] U.S. Congress. Joint Committee on Federal Aid in the Construction of Post Roads. Final report entitled Federal Aid to Good Roads, printed as House Document No. 1510, 63rd Congress, 3rd Session. Washington: Government Printing Office 1915, pp. 22-23.

[10] 39 Stat. 355.

[11] Stewart, Budget Reform Politics, p. 187; also section 9 of the Legislative, Executive and Judicial Appropriations Act, 1923 (37 Stat. 360, at 415).

[12] H.R. 9783, 66th Congress.

[13] George B. Galloway, History of the United States House of Representatives (Washington: GPO, 1962 –H. Doc. 246, 87th Congress) p. 160.

[14] U.S. Senate. Committee on Appropriations. United States Senate Committee on Appropriations, 138th Anniversary, 1867-2005 (Washington: GPO, 2005 – S. Doc. 109-5), p. 12.

[15] David Brady and Mark A. Morgan, “Reforming the Structure of the House Appropriations Process: The Effects of the 1885 and 1919 Reforms on Money Decisions,” in Congress: Structure and Policy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987), Matthew McCubbins and Terry Sullivan, Eds., pp. 224-226.

[16] John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project [online]. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California (hosted), Gerhard Peters (database). Available from World Wide Web: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29634.

[17] House Report No. 373, 66th Congress, 1st Session, p. 10.

[18] Richard F. Fenno, Jr., The Power of the Purse: Appropriations Politics in Congress (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966) p. 45.

[19] 40 Stat. 1189, 1201 (1919).

[20] Bureau of Public Roads, Annual Report, 1921, p. 6.

[21] Congressional Record, 67th Congress, 1st Session, October 27, 1921, p. 6897.

[22] Letter from Andrew W. Mellon to Warren G. Harding, November 4, 1921. Carbon copy of original located in the Records of the Bureau of the Budget, General Subject File Series 21.1, Box 228 (R&H (Green River, Ut.-Roads #1), folder “Roads #1 Thru 12/32” at the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[23] Letter from Warren G. Harding to Andrew W. Mellon, November 7, 1921. Carbon copy of original located in the Records of the Bureau of the Budget, General Subject File Series 21.1, Box 228 (R&H (Green River, Ut.-Roads #1), folder “Roads #1 Thru 12/32” at the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[24] Budget of the United States for the Service of the Fiscal Year Ending June 30 1923 (Washington: GPO, 1921 – H. Doc. No. 126, 67th Congress), p. xv.

[25] FY 1923 Budget, p. xiv.

[26] FY 1923 Budget, pp. xiv-xv.

[27] Congressional Record (bound edition), January 18, 1922, p. 1320.

[28] Congressional Record (bound edition), January 18, 1922, p. 1325.

[29] Congressional Record (bound edition), March 6, 1922, p. 3431 (text of S. Res. 214 as agreed to).

[30] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, p. 8255.

[31] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, p. 8286.

[32] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, p. 8286.

[33] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, pp. 8284-8285.

[34] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, p. 8285.

[35] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, pp. 8285-8286.

[36] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 6, 1922, p. 8289.

[37] 42 Stat. 660 (1922).

[38] 43 Stat. 889 (1925).

[39] 43 Stat. 822, 852 (1925).

[40] Comptroller General opinion B-211190, April 5, 1983.

[41] Train v. City of New York, 420 U.S. 35, 39 n.2 (1975).

[42] America’s Highways 1776-1976, p. 206.

[43] U.S. General Accounting Office, Inventory of Accounts With Spending Authority and Permanent Appropriations, 1996 (GAO/AIMD-96-79).

[44] Office of Management and Budget. Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2008 (Washington: GPO, 2007) p. 400.