September 5, 2018

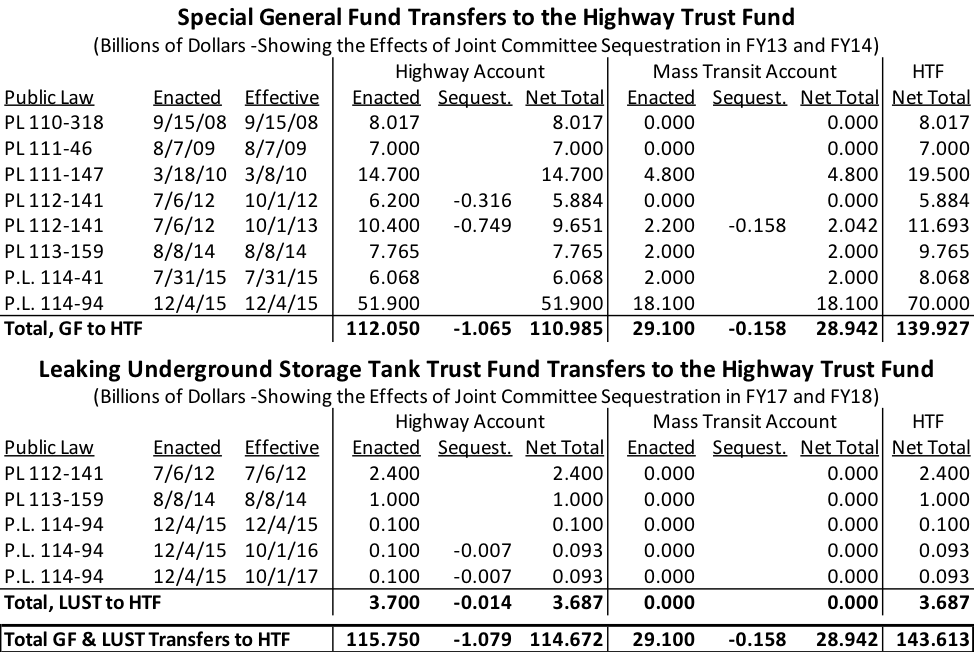

Ten years ago today, the U.S. Department of Transportation made the stunning announcement that the federal Highway Trust Fund had run out of money and that state governments would no longer be guaranteed speedy reimbursement for the federal-aid highway expenses that the states had already incurred. The announcement prompted an immediate $8 billion bailout by Congress in the form of a transfer of moneys from the general fund of the Treasury to the Trust Fund.

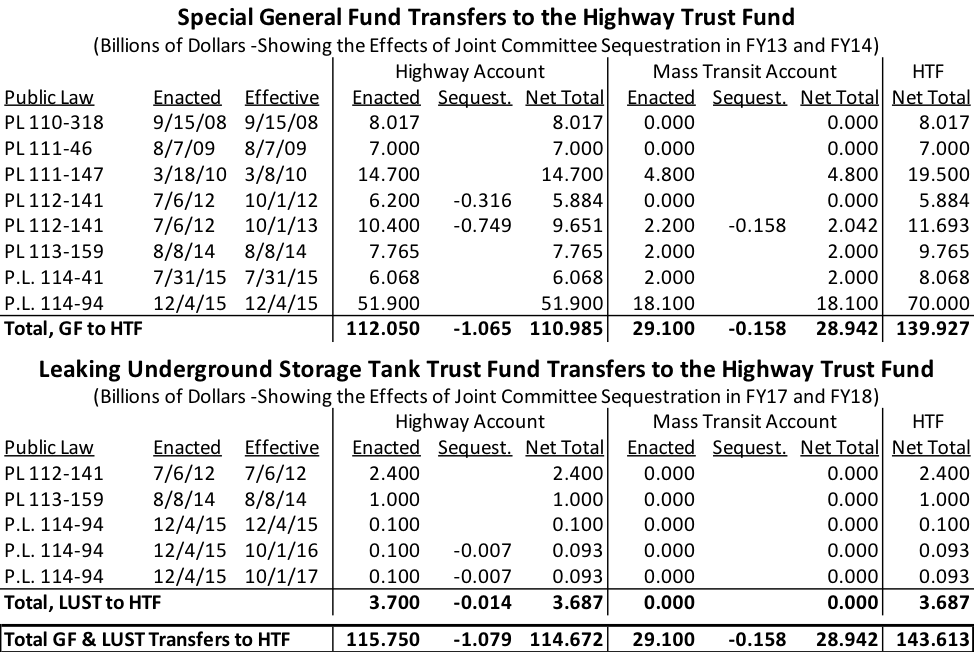

In the decade since then, rather than put the Trust Fund back in a position where its spending levels more or less equal its dedicated excise tax receipt levels from year to year, Congress has instead provided another $135.6 billion in bailouts, for a total of $143.6 billion ($139.9 billion from the general fund and $3.7 billion from gasoline and diesel taxes originally deposited in a different trust fund).

How did the venerable Highway Trust Fund – the financial instrument that built the Interstate Highway System, which transformed American life – get in such dire straits? And are we any closer to being able to fix it?

Part 1 – How to Bankrupt Your Trust Fund in Four Easy Steps

Step 1. Tie actual spending to estimated revenues. The 1998 TEA21 law represented a major victory for the House and Senate transportation authorizing committees over their arch-rival Appropriations Committees in their two-decade contest over who got to set the final funding levels and conditions on Highway Trust Fund spending programs. Not only did TEA21 amend budget law and House rules to make it difficult-to-impossible for the appropriators to reduce annual Trust Fund spending below the levels spelled out in TEA21, the law also provided for automatic adjustments to those spending levels that its authors said were supposed to ensure that all new Trust Fund income from highway user taxes would actually be spent.

The lead sponsor of the legislation, House Transportation and Infrastructure chairman Bud Shuster (R-PA), told the House on the day they adopted the conference report that:

What it means, if we do spend the revenue going into the trust fund, and not a penny more, only the revenue going into the trust fund, means that this bill over six years can guarantee $200,500,000,000 spending, because that is the revenue projected to go into the trust fund.

Should there be more revenue going into the trust fund, that money will be available to be spent. Should there be less revenue going into the trust fund, then we will have to reduce the expenditures. It is fair, it is equitable, and it is keeping faith with the American people.

-Bud Shuster, May 22, 1998

However, the new process, called “revenue aligned budget authority,” or RABA for short, allowed highway spending to increase based on estimated future tax receipt levels, not on actual tax receipts themselves. Such estimates are never quite accurate – and sometimes they are way off indeed.

The Treasury/OMB forecasts for each year’s Highway Trust Fund Highway Account tax revenues, as of spring 1998, were written into the text of section 8101 of the TEA21 law. Then the law provided that, for an upcoming budget year, if the updated Treasury/OMB tax estimates for Highway Account tax receipts were higher than the previous estimates written into sections 8101, highway formula funding in that amount would automatically be created and given to states. After two years, a “look-back” component would be added to the RABA calculation to correct for whether or not actual tax receipts in the Highway Account had been above or below the section 8101 TEA21 estimates.

TEA21 was signed into law in June 1998, and since the RABA calculation relied on the latest tax estimates from the President’s Budget, the first year of RABA was that for the next budget year, FY 2000. In those first three years, RABA added almost $9.1 billion in real highway funding.

| RABA – The First Three Years |

| (Millions of dollars of federal-aid highways obligation limitation) |

|

FY 2000 |

FY 2001 |

FY 2002 |

3-Year |

| TEA21 Authorized |

26,245 |

26,696 |

27,290 |

80,231 |

| RABA Look-Ahead |

+485 |

+1,862 |

+2,760 |

+5,107 |

| RABA Look-Back |

+971 |

+1,196 |

+1,783 |

+3,950 |

| Other Adjustments |

0 |

-92 |

-34 |

-116 |

| Total Highway Ob. Limit |

27,701 |

29,754 |

31,799 |

89,254 |

| RABA Increased TEA21 by: |

+5.5% |

+11.5% |

+16.6% |

+11.0% |

However, even as states were starting to commit their record-high fiscal 2002 highway apportionments, a big problem was emerging. The fiscal year 2001 Highway Account tax receipt estimate written into section 8101 of TEA21 in spring 1998 was $28.5 billion. By the time the FY 2001 President’s Budget came out, in January 2000, Treasury and OMB had increased that estimate to $30.4 billion, and on that basis, RABA gave highway funding a “look-ahead” boost of $1.9 billion in 2001.

But by the time the books had closed on FY 2001, a few months after the fiscal year ended on September 30, actual Highway Account tax receipts were only $26.9 billion – $1.6 billion less than the original TEA21 estimate and $3.5 billion less than the revised estimate on which the FY01 RABA money was given out. And the revised Treasury/OMB tax receipt estimates for 2003 were about $900 million lower than originally predicted in TEA21. (See this May 2002 GAO testimony for details.)

When the President’s Budget for fiscal 2003 (the last year of the TEA21 law’s authorizations) came out, it called for the first “negative RABA,” a reduction of $4.4 billion ($3.5 billion from the look-back to correct the bad FY 2001 estimates and $0.9 billion from the FY 2003 look-ahead). And since this negative $4.4 billion came on the heels of a FY 2002 program that had been beefed up by $4.5 billion in positive RABA, this would represent a 26 percent contraction from the program size provided just a year before.

|

FY 2002 |

FY 2003 |

Change |

| TEA21 Authorized |

27,290 |

27,746 |

+456 |

1.6% |

| RABA Look-Ahead |

+2,760 |

-901 |

|

|

| RABA Look-Back |

+1,783 |

-3,468 |

|

|

| Total Highway Program |

31,799 |

23,377 |

-8,456 |

-25.9% |

In the fiscal 2003 budget cycle, Congress would have to decide whether or not to fulfill former chairman Shuster’s promise (he retired in early 2001) that “Should there be less revenue going into the trust fund, then we will have to reduce the expenditures.”

Step 2. Hold the highway program harmless for faulty revenue estimates. Even before the President’s Budget for FY 2003 was released in early February 2002, word on the massive “negative RABA” adjustment had leaked out. Lobbyists for the road builders had deduced a problem months before from the monthly Treasury reports of actual Trust Fund tax receipts and had written to Treasury and to the Transportation Department in September 2001 to sound the alarm. More detailed word that a major negative RABA adjustment was forthcoming came with the release of an OMB scorekeeping report on January 18, 2002.

On the day the budget was released, Office of Management and Budget Director Mitch Daniels explained in a press briefing that in fiscal 2001, “economists missed the recession, basically, and we spent $4.5 billion more than the [highway] formula, than an accurate estimate would have produced. So we, in essence, spent it ahead; now we’re going to let revenues catch up.” He went on:

Now, I don’t have a lot of sympathy for people who sort of love this formula when it overpays and don’t like this formula when it corrects itself. You know, it’s like playing Monopoly with somebody who draws the “bank error in your favor” card one time and thinks they ought to get it every time around the board. It doesn’t work that way.

-OMB Director Mitch Daniels, February 4, 2002

As luck would have it, the transportation construction industry’s annual legislative “fly-in” was scheduled to begin in DC on the day after the budget was released, and construction industry and labor union leaders immediately blanketed Capitol Hill with requests to cancel the negative RABA adjustment called for by the TEA21 law. Three days after the budget was released, the chairman and ranking minority member of the House T&I Committee had introduced a bill (H.R. 3694, 107th Congress) along with 72 of their bipartisan colleagues to cancel the negative RABA adjustment “notwithstanding any other provision of law” and set the 2003 highway obligation limitation at $27.7 billion, the level originally called for in TEA21.

On the same day H.R. 3964 was introduced, T&I held a previously scheduled hearing on TEA21 reauthorization where RABA was a major point of contention. Federal Highway Administrator Mary Peters gave a more detailed explanation of the negative adjustment:

The predominant factors that affected the negative RABA in this cycle were two. One was the sale of commercial trucks, new trucks, which was down 45-plus percent. That perhaps can be looked at as a point in time issue, rather than a point over time issue, and certainly additional analysis is continuing on that.

But the other factor was, we saw a 28-plus percent increase in the use of ethanol and a corresponding decrease in the use of gasoline. Because ethanol does not contribute to the Highway Trust Fund at the same rate as gasoline, certainly that was a more negative effect.

-FHWA Administrator Mary Peters, February 7, 2002

Several legislators at the hearing quoted from a chart generated by the construction industry showing how a reduction of $8.5 billion from the 2002 funding levels would be distributed on a state-by-state basis (factual) and then extrapolating how many construction jobs would be lost because of the cut (largely untrue, because the economic effect of the $4.4 billion increase in 2002 over 2001 had not begun to be felt yet).

Six days later, the number of House cosponsors of H.R. 3694 had risen above 220, a bare majority of the House, and a memo to Associated General Contractors members from their DC office said that “A full-out assault is still needed to drive the cosponsors to over 300 in the House.” The memo then indicated that the construction industry would not be content simply to restore funding to the levels originally promised in the TEA21 law – the industry wanted to lock in the higher 2002 level based on the faulty tax estimates as the new baseline moving forward, forever:

Once we succeed in gaining overwhelming support for increasing funding by $4.4 billion (the amount called for in TEA-21), we will push to increase funding by a total of $8.6 billion, to match the record funding level for this current fiscal year 2002.

-Associated General Contractors of America newsletter, February 14, 2002

On February 25, 46 state governors wrote a letter to the Congressional leadership urging that the FY 2003 highway funding total be set at the mistakenly-inflated 2002 total of $31.8 billion, not the $27.7 billion originally called for in TEA21. A similar letter was sent to President Bush and signed by the heads of the National Governors Association, the association of state DOTs, the association of mass transit agencies, the highway users, and construction industry and labor leaders.

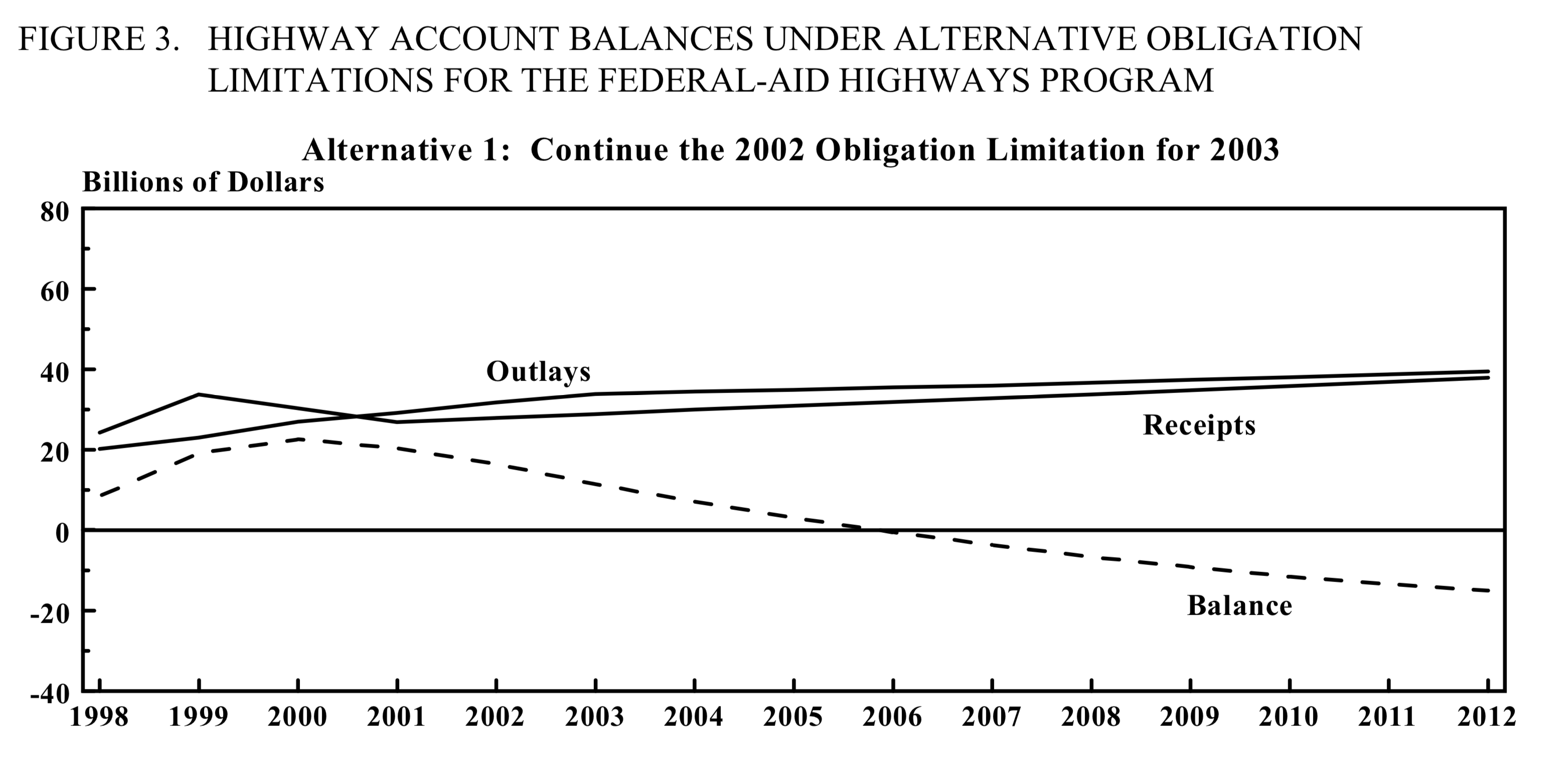

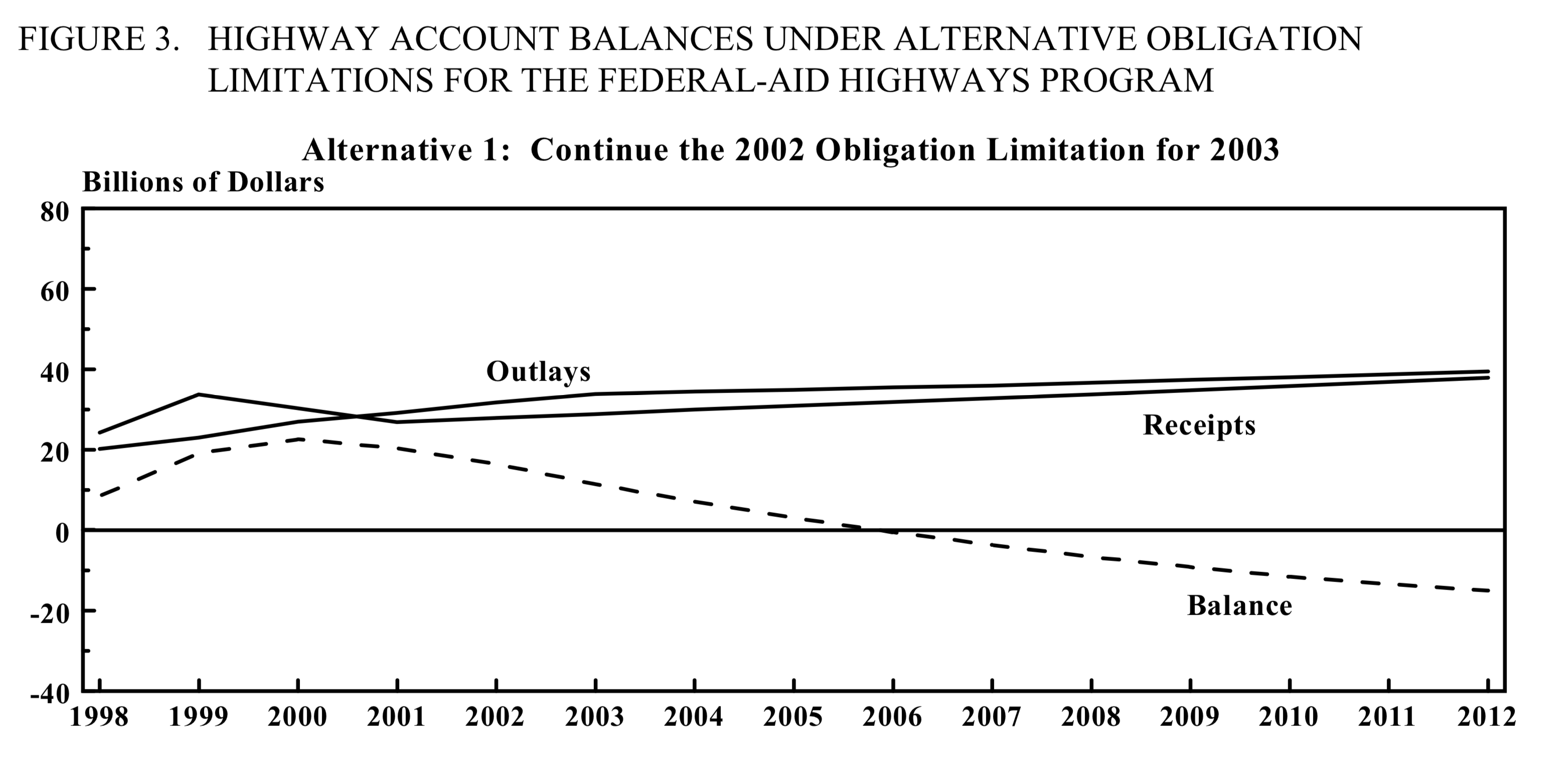

A month later, on March 22, the House T&I Committee held a hearing on the Highway Trust Fund situation. At that hearing, the Congressional Budget Office submitted testimony that analyzed the long-term effects of several different funding scenarios. That testimony specifically warned the committee that continuing a highway obligation limitation level of $31.8 billion per year was unsustainable and would bankrupt the Highway Account of the Trust Fund by 2007 under current tax revenue projections:

Source: Congressional Budget Office, May 2002

CBO suggested that a 2003 obligation limitation of $30.1 billion was the most that could be indefinitely supported (with annual inflation increases) by the Highway Account.

In the Senate, the chairman and ranking member of the Environment and Public Works Committee and introduced a bill identical to H.R. 3694 on the same day as that bill (S. 1917, 107th Congress) with 17 original cosponsors, and the number of total sponsors and cosponsors grew to a total of 65 – almost two-thirds of the Senate, and over the 60 necessary to break a filibuster or bust the budget – within one month of introduction. On February 26, Senate Budget Committee chairman Kent Conrad (D-ND) made it clear at a hearing that he would not use his leverage as guardian of the budget process to get in the way of extra highway spending: “We are not going to be cutting $8.6 billion around here. There is no support for that. I have not talked to a single member on the House or the Senate side that thinks that that is a responsible thing to do.”

There was resistance in the House by the Appropriations Committee, which was still sore over being largely locked out of the Highway Trust Fund funding decisions by TEA21. The membership of that panel introduced their own bill on March 7 (H.R. 3900, 107th Congress) that would have nullified the negative RABA adjustment to the highway and transit “firewalls” established by TEA21 but left the appropriators free to choose their own final spending level for the program in 2003.

Things came to a head in May, as the House prepared to debate an emergency supplemental appropriations bill. T&I marked up its bill on May 1 and unanimously reported the bill with a few technical changes. The following week, a deal was reached where the Appropriation Committee would include language in their bill that week deeming the RABA adjustment for 2003 to be zero, and the House would later take up the T&I bill. Appropriations reported their bill (H.R. 4775, 107th Congress), and section 1402 nullified the downwards RABA adjustment but did not set a final number. The House then passed H.R. 3694 on May 14 by a roll call vote of 410 to 5. (Ed. Note: Two of the five “no” votes went on to be come U.S. Senators – Jeff Flake (R-AZ) and Rand Paul (R-KY).)

The appropriations bill contained $29 billion of “must-pass” funding for post-9/11 reconstruction and military operations in Afghanistan, so it was on a faster track than the T&I/EPW bill. Senate Appropriations reported its own version of the bill on May 22 (S. 2551, 107th Congress), and section 1002 of that bill handled things differently – it simply said that the final FY 2003 highway obligation limitation should be between $27.7 billion (the TEA21 level) and $28.9 billion ($3.0 billion less than FY 2002). (Ed. Note: The only cosponsor of the EPW bill who later removed themselves was Patty Murray (D-WA), who was presumably told by Chairman Byrd that appropriators were not supposed to support outside legislation that tied their own hands.)

Two days later the House version of the appropriations bill passed by 280-138 without a single mention of the RABA provision. The Senate passed the bill with its amendment just after midnight on the morning of June 7 by a vote of 71 to 22. It took negotiators until July 19 to agree on the final conference report version of the legislation, which included the House provision resetting the guaranteed highway obligation limitation level back to $27.7 billion (this was enacted as Public Law 107-206).

But by this point, the regular FY 2003 DOT appropriations bill was already working its way through the House and Senate. Senate appropriators reported their bill first (S. 2808, 107th Congress) and it went ahead and set the highway number at the previous year’s (unsustainable) $31.8 billion. The House version was not reported until October 1 (H.R. 5559, 107th Congress), which set the number at the original (sustainable) TEA21 level of $27.7 billion. However, Congress broke for the mid-term elections in mid-October, and in those elections, the GOP took control of the Senate as well as the House, so a decision was made to postpone final FY 2003 appropriations action until the new Congress could deal with it in January.

At the start of the new Congress, on January 8, 2003, the House passed a simple three-page “clean” continuing resolution through January 31 (H. J. Res. 2, 108th Congress). New Senate Appropriations chairman Ted Stevens (R-AK) then offered a mammoth amendment with the text of the Senate version of all eleven unfinished FY03 appropriations bills, including a DOT bill with a $31.8 billion highway number. The White House issued a Statement of Administration Policy on the Senate package on January 17 stating “The bill also proposes an unsustainable level of spending for highways, which breaks dramatically with the traditional linkage of highway spending and trust fund revenues. This would put the program on a path to an inevitable gas tax increase, which the Administration strongly opposes.” But the SAP did not threaten a veto, and Congress often ignores SAPs unless they contain a credible veto threat.

The threat posed to the Highway Account by a $31.8 billion highway funding level was reiterated by the Congressional Budget Office in its January 30, 2003 annual baseline outlook, which predicted that a $31.8 billion highway obligation limitation in 2003, if extended annually with standard inflation adjustments, would bankrupt the Highway Account in five years without extra revenues:

| CBO January 2003 HTF Baseline |

| Billions of dollars. |

|

|

FY03 |

FY04 |

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

| HTF Highway Account |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Highway Ob. Limit |

31.8 |

32.3 |

33.0 |

33.7 |

34.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beginning-of-FY Balance |

16.1 |

10.6 |

6.1 |

3.0 |

0.7 |

|

Receipts |

28.7 |

30.0 |

31.4 |

32.4 |

33.4 |

|

Outlays |

34.2 |

34.5 |

34.4 |

34.8 |

35.2 |

|

End-of-FY Balance |

10.6 |

6.1 |

3.0 |

0.7 |

-1.1 |

But the Senate passed the amended omnibus resolution on January 23 without reducing the highway amount and went straight to conference with the House, despite the fact that the House did not, technically, have its own appropriations bills in conference as well. Congressional leaders were in a rush to finish the business of the last Congress so they could get busy with the agenda of the at-long-last-unified Republican government, so a conference report on the omnibus appropriations package was filed on February 13, which (surprise, surprise) completely ceded to the Senate’s unsustainable $31.8 billion highway funding level.

Some of the more fiscally responsible legislators who nonetheless supported the unsustainably high spending level reassured themselves that 2003 was the last year of the TEA21 surface transportation authorization, and Congress had to reauthorize the program starting with fiscal 2004. It was hoped that the new reauthorization bill would provide an opportunity the authorizing committees to put the Trust Fund on a sound financial footing for the long term.

Step 3. Intentionally put the Trust Fund on a “glide path” to insolvency. The coalition that supports ever-higher spending from the Highway Trust Fund consists of state and local governments, the construction industry, labor unions, the Chamber of Commerce and other business interests, and the members of Congress who listen closely to all of the above. That coalition is sometimes regarded as an irresistible force, but in the 2003-2005 period, it met an immovable object named George W. Bush. Specifically, they were unable to dislodge Bush from his implacable opposition to a gasoline tax increase.

Former Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta (a member of the Eno Center Board of Directors) has often told the story of going into the Oval Office to pitch President Bush on USDOT’s draft TEA21 reauthorization plan, which included a gas tax increase. When they got to the gas tax page in the printout of Mineta’s slide deck, Bush took out a Sharpie and just marked right through it. The White House was not going to support a gas tax increase, and with a Republican House and Senate, the chances of the putative anti-tax party putting together two-thirds margins to override a veto of a gas tax increase were always low.

The Bush Administration submitted its proposed reauthorization bill in May 2003, which called for $238.9 billion in Trust Fund spending over six years, with the highway obligation limitation dropping back down to $29.3 billion in 2004 then rising year-by-year to $33.9 billion in 2009. Under the Administration plan, highway spending would not top the 2003 levels again until 2007.

This didn’t stop Republicans on the transportation committees from trying for a gas tax increase. House T&I chairman Don Young (R-AK) wrote a secret memo to White House Chief of Staff Andy Card on December 3, 2002 advocating an increase in gasoline and diesel taxes of 2 cents per year plus inflation indexation. On March 12, 2003, Young and his ranking minority member Jim Oberstar (D-MN) held a press conference to announce their support for a six-year, $375 billion surface transportation reauthorization predicated on a gas and diesel tax increase (described at the press conference only as inflation indexation, but with an assumed receipt total that clearly meant retroactive indexation back to 1993 as well as moving forward).

But revenue increases for the Highway Trust Fund are not in the jurisdiction of the T&I Committee – they are the purview of the Ways and Means Committee. Young and Oberstar introduced their $375 billion bill (H.R. 3550, 108th Congress) in November 2003, but it couldn’t move until Ways and Means decided how much extra money (if any) to give to the Trust Fund. The situation was the same in the Senate, where the Environment and Public Works Committee approved legislation in November 2003 (S. 1072, 108th Congress) but could not move its bill until the Finance Committee found money.

Both Ways and Means and Finance rejected excise tax rate increases and instead concentrated on fixing problems in the scope and coverage of existing taxes. The main focus was ethanol – under the law in existence at the time, ethanol-blended motor fuels (gasohol) paid a lower tax rate than gasoline, and in addition, the cost of the federal tax credit for ethanol was paid by the Trust Fund, not the general fund. Thomas reached an agreement with Finance chairman Chuck Grassley (R-IA) in November 2003 on new tax treatment of ethanol. Both committees included such proposals in their revenue plans, as well as provisions fighting fuel tax fraud and other odds and ends. (The Senate plan also addressed the issue of “floor stocks” refunds.)

All of these provisions (except the tax fraud and Senate floor stocks provisions) were simply switching costs or revenue streams from the general fund to the Trust Fund. Floor stocks aside, both bills would have raised $13.5 billion over five years for the Trust Fund according to the JCT analysis. The tax titles were plugged into the House and Senate bills (and the House bill was downsized considerably from the original $375 billion), and both chambers passed bills. But the White House threatened to veto both versions of the bill (see the veto threat of the House bill here and of the Senate bill here) based largely on overall spending level, and refused to budge. The transportation bill died in House-Senate conference.

Meanwhile, the tax committees took the ethanol tax credit provisions from the transportation bill and put them into a separate tax bill that was enacted in October 2004 as Public Law 108-357. This meant that those revenues would be built into the tax baseline when the new budget came out in early 2005.

When the new 109th Congress convened in January 2005, the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline funding projections for the Highway Trust Fund (with all of the extra Highway Account revenues from the enacted ethanol fix) looked like this:

| CBO January 2005 Highway Trust Fund Baseline |

| Billions of Dollars |

|

|

|

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

| Highway Account |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Budgetary Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Highways Oblim |

34.3 |

34.8 |

35.4 |

36.0 |

36.7 |

37.4 |

38.1 |

38.7 |

39.4 |

40.2 |

40.9 |

|

|

Discretionary ER BA |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

|

|

Exempt Contract Auth. |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

Safety Resources |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

|

Total Resources |

37.8 |

38.4 |

39.1 |

39.8 |

40.5 |

41.2 |

42.0 |

42.7 |

43.5 |

44.3 |

45.1 |

|

Cash Flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beginning-of-FY Balance |

10.8 |

10.5 |

9.3 |

7.8 |

6.5 |

5.5 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

4.8 |

5.3 |

|

|

Receipts |

33.9 |

35.4 |

36.6 |

37.8 |

38.9 |

39.9 |

40.9 |

41.8 |

42.8 |

43.8 |

44.8 |

|

|

Outlays |

34.2 |

36.6 |

38.1 |

39.1 |

39.8 |

40.4 |

41.1 |

41.9 |

42.7 |

43.2 |

44.3 |

|

|

End-of-FY Balance |

10.5 |

9.3 |

7.8 |

6.5 |

5.5 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

4.8 |

5.3 |

5.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mass Transit Account |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Budget. Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FTA Oblim |

6.7 |

6.8 |

6.9 |

7.0 |

7.2 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cash Flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOY Balance |

3.8 |

2.1 |

0.6 |

-0.9 |

-2.3 |

-3.6 |

-4.9 |

-6.2 |

-7.4 |

-8.7 |

-9.9 |

|

|

Receipts |

5.1 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

6.7 |

|

|

Outlays |

6.8 |

6.9 |

7.0 |

7.1 |

7.2 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.8 |

8.0 |

|

|

EOY Balance |

2.1 |

0.6 |

-0.9 |

-2.3 |

-3.6 |

-4.9 |

-6.2 |

-7.4 |

-8.7 |

-9.9 |

-11.1 |

At projected 2004-plus-inflation spending levels, the Highway Account looked to be solvent indefinitely. It was the Mass Transit Account that was about to go broke. Raising extra taxes just for mass transit was a political non-starter, so the House and Senate tried an accounting gimmick instead. Under the system in place at the time, every dollar spent by the Federal Transit Administration was drawn 80 cents from the Trust Fund and 20 cents from the general fund. But Treasury rules required that the moment FTA obligated a dollar by approving a contract or project, the entire amount of the obligation was transferred from the HTF to the GF immediately, to wait for years and years for eventual expenditure.

In early 2005, the House T&I staff had CBO do a separate run under a new scenario – what if the FTA spent (obligated) the exact same amount of money each year, but Congress got rid of the split-funding of each account and just created one account for the Trust Fund money and other accounts for the general fund spending? Under that scenario, the outlay rate would reset to a new zero starting point on October 1, 2006 and then build back up slowly, so the same amount of annual funding provided by Congress went from an $11 billion Mass Transit Account deficit at the end of 10 years to a $5 billion positive balance at the end of the same period.

| CBO January 2005 HTF Mass Transit Account Baseline With Alternative Scenario – Identical Spending Levels but Ending the 80-20 Split-Funding of Every Dollar Spent |

|

|

|

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

|

Cash Flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOY Balance |

3.8 |

2.1 |

6.3 |

8.7 |

9.9 |

10.1 |

9.6 |

8.6 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

5.7 |

|

|

Receipts |

5.1 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

6.7 |

|

|

Outlays |

6.8 |

1.1 |

3.1 |

4.5 |

5.6 |

6.5 |

7.2 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

|

|

EOY Balance |

2.1 |

6.3 |

8.7 |

9.9 |

10.1 |

9.6 |

8.6 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

5.7 |

4.8 |

The revenue title for the final SAFETEA-LU conference agreement in summer 2005 kept the previous ethanol gains and added another $500 million per year or so for the Trust Fund (JCT score here), mostly from redefining the difference between aviation fuel and highway fuel. The final agreement increased program spending significantly above a baseline which had already been beefed up via spending increases in the two years of short-term funding extensions. (Much of the program increase was ending the practice of taking annual appropriations for road rebuilding after hurricanes, floods and earthquakes from the Trust Fund and taking that money out of the general fund instead – emergency relief naturally only goes to where the hurricane/flood/earthquake hit, while regular Trust Fund money was to be distributed via hard-fought formulas and earmarks to all 50 states, DC, and territories.) Solvency of the Mass Transit Account was dealt with via the outlay rate reset described above, and the extra Highway Account spending was “paid for” by spending anticipated balances down to near zero by the end of the bill, on a trend where default was certain within a year after the bill was set to expire.

| CBO Highway Trust Fund Baseline Immediately After Enactment of SAFETEA-LU |

| Billions of dollars. |

|

|

|

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

| Highway Account |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Budget. Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F-AH Oblim |

34.2 |

36.0 |

38.2 |

39.6 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

41.2 |

|

|

Discr. ER BA |

1.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Exempt CA |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

Safety |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

|

Total Resources |

37.8 |

38.0 |

40.2 |

41.6 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

43.2 |

|

Cash Flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOY Balance |

10.8 |

11.1 |

10.0 |

7.4 |

4.0 |

0.4 |

-3.2 |

-6.2 |

-8.6 |

-10.2 |

-10.8 |

|

|

Receipts |

33.4 |

35.2 |

36.1 |

37.1 |

38.2 |

39.1 |

40.0 |

40.8 |

41.7 |

42.5 |

43.4 |

|

|

Outlays |

33.1 |

36.3 |

38.7 |

40.5 |

41.8 |

42.6 |

43.1 |

43.2 |

43.3 |

43.2 |

43.4 |

|

|

EOY Balance |

11.1 |

10.0 |

7.4 |

4.0 |

0.4 |

-3.2 |

-6.2 |

-8.6 |

-10.2 |

-10.8 |

-10.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mass Transit Account |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Budget. Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FTA Oblim |

6.7 |

7.0 |

7.3 |

7.9 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

|

Cash Flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOY Balance |

3.8 |

2.0 |

6.1 |

8.2 |

9.0 |

8.5 |

7.1 |

5.0 |

2.8 |

0.7 |

-1.3 |

|

|

Receipts |

5.0 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

6.0 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

|

|

Outlays |

6.8 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

4.8 |

6.1 |

7.3 |

8.0 |

8.2 |

8.3 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

|

|

EOY Balance |

2.0 |

6.1 |

8.2 |

9.0 |

8.5 |

7.1 |

5.0 |

2.8 |

0.7 |

-1.3 |

-3.2 |

In the short term, the Highway Account was in the most peril, as CBO projected the account to be running on fumes at the end of FY 2009 (which likely meant day-to-day insolvency before September 30). But in the long term, the spending-versus-revenues imbalance set by SAFETEA-LU was worse for the Mass Transit Account. At the end of 10 years, CBO projected the Highway Account to break even in terms of cash flow, as the growth of tax receipts would catch up with spending levels. But at the end of 10 years, CBO projected Mass Transit Account spending to be $2.0 billion, or 31 percent, per year higher than tax receipts.

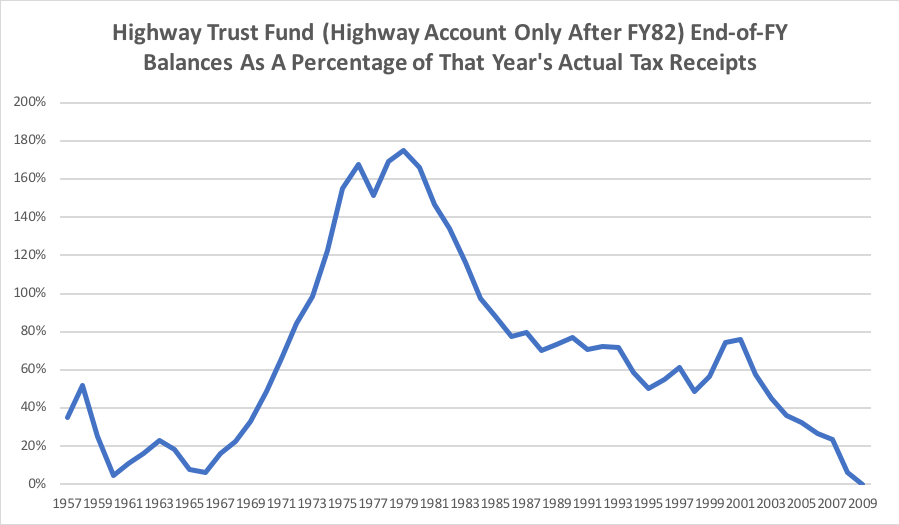

Step 4. Repeal or neuter existing spending controls and institutions. The decision to “spend down” Trust Fund balances to zero shortly after the end of the authorization bill required Congress to repeal the self-sufficiency requirement placed in the law creating the Highway Trust Fund in 1956 by Senate Finance Committee chairman Harry Byrd (D-VA). Called the “Byrd Test” after its originator, the provision (found in section 209(g) of the original 1956 Act and later codified in section 9503(d) of the Internal Revenue Code) requires automatic reductions in the apportionments of new contract authority each year if they would cause the total amount of contract authority available (including prior year money) to exceed the latest Treasury projections of Trust Fund tax receipts.

As recodified in 1982, the Byrd Test for highways required the total unfunded highway contract authority to be weighed against existing Highway Account balances plus the forthcoming two fiscal years of revenues. The +2 year calculation could be justified because Trust Fund taxes traditionally extend for two years longer than new spending authorizations last, which dates back to the original 1956 law, which assumed that the Trust Fund was a temporary construct, and that it would take 13 years worth of contract authority and 15 years worth of outlays to build the entire Interstate system, after which The Trust Fund would expire and taxes would revert back to their pre-1956 levels.

The Byrd Test was triggered a few times in the first five years of the program (the last time was FY 1961). As the highway program was operating under the short-term extensions in 2003-2005, the Byrd Test was triggered in August 2004. According to a FHWA announcement, unfunded contract authority then totaled $62.5 billion versus only $61.7 billion of Highway Account balances and future receipts, so an across-the-board cut of $728 million in new highway formula money was ordered.

Note that the Highway Account still had a positive cash balance of $7.8 billion as of the end of August 2004. The Byrd Test served as a “slow down” signal – so, of course, it was promptly waived temporarily by Congress by section 13(f) of the next extension law enacted in September 2004.

Meanwhile, the Senate Finance Committee had already proposed to effectively neuter the Byrd Test by extending the revenue calculation to include four future years of tax revenues instead of two – even though, by law, the tax revenues only lasted two years longer than the spending. ETW’s predecessor publication calculated at the time that this would allow the Highway Account to reach bankruptcy and then go over $70 billion into the red before the Byrd Test was triggered. Nevertheless, section 11102 of SAFETEA-LU changed the Byrd Test calculation from two years to four years, because that was the only way to allow the Trust Fund to be put on a “glide path” to insolvency shortly after the expiration of the authorization law. This made the Byrd Test essentially worthless as a means of making the Trust Fund “deficit-proof” (as the HTF’s advocates used to claim it was).

This would not have been possible if certain institutional guardians of the Treasury had not been co-opted. The Trust Fund is technically the responsibility of the tax committees, not the transportation committees. But Ways and Means chairman Thomas was probably more concerned about the gobsmacking $750+ million in earmarks that he got in SAFETEA-LU than he was about the long-term solvency of the Trust Fund. (Ed. Note: On the day Congress passed the SAFETEA-LU conference agreement, I told conferee Peter DeFazio (D-OR) that I was having real trouble wrapping my head around Bill Thomas getting $750 million in earmarks. DeFazio told me that it was a “finder’s fee” for Thomas finding every odd-and-end available in the tax code to beef up Trust Fund balances without raising taxes.)

Likewise, part of the institutional role of the Budget Committees is to call out and try to head off looming fiscal disasters, but House Budget Committee chairman Jim Nussle (R-IA) may have been preoccupied by his need for money for a new bridge across the Mississippi River between Bettendorf in his district and Moline, Illinois. (See section 1114 of SAFETEA-LU – the final bill gave Nussle’s bridge $35 million in the same section of the bill that took care of Don Young’s “Bridge to Nowhere” as well as leadership priorities for Pelosi, Reid, Inhofe, Jeffords, Bond, and DeFazio.)

(Not to mention how the Speaker of the House’s attitude towards the bill was colored by his $207 million earmark for the Prairie Parkway in Illinois – unbeknownst to others, the Speaker secretly owned real estate near the project’s right of way, which he then sold for a $3 million profit, according to the Washington Post.)

Senate Budget Committee chairman Judd Gregg (R-NH) did protest, but when a bill has well over 60 votes in the Senate, it largely neutralizes the procedural leverage held by the Budget chairman. Gregg was one of the four Senators to vote “no” on the SAFETEA-LU conference report (the others were Cornyn (R-TX), Kyl (R-AZ), and McCain (R-AZ)). The bill passed the House by an even wider percentage margin, 412 to 8. Clearly, the long-term solvency of the Highway Trust Fund was not foremost in the minds of legislators at the time.

To the extent that long-term Trust Fund solvency was on anyone’s mind in 2005, it was in the form of hopes by the members of the 109th Congress that the members of the future 110th or 111th Congresses would fix the problem that they could not fix. To help them out, SAFETEA-LU created not one but two blue-ribbon panels (in sections 1909 and 11142 of the law) that were to study the problem and recommend ways to make the Trust Fund financially sound. Their reports were to be made to Congress starting in 2007, in plenty of time for Congress to avert the scheduled Trust Fund bankruptcy.

Part 2 – What Happens When Your Trust Fund Runs Out of Money

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

-Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Gradually. From the moment that SAFETEA-LU was sent to President Bush for signature in August 2005, it was obvious that the spending levels in the bill were not sustainable. The projection of the Congressional Budget Office at the time Congress agreed to the conference report anticipated that the Highway Account would run out of money late in fiscal year 2009, but there were a lot of variables. The RABA experience under TEA21 had taught a hard lesson in the volatility of revenue estimates, and SAFETEA-LU still retained some ability to increase spending based on faulty tax receipt estimates as well.

But “sometime in 2009” was four years away. There were not one but two Congressional election cycles between the summer of SAFETEA-LU and then, one of which was a Presidential election year.

The OMB/Treasury forecasts for Trust Fund cash flow were usually several billion dollars more negative than CBO’s. In its first post-SAFETEA-LU budget (FY 2007), the Bush Administration requested the full SAFETEA-LU highway obligation limitation of $39.1 billion, which included $842 million of positive RABA.

But the following year, OMB forecast that the end-of-2009 Highway Account shortfall would be $2.3 billion, so the FY 2008 Bush budget kept the SAFETEA-LU highway number but proposed dispensing with the upwards RABA adjustment of $631 million “in order to preserve the solvency of the Highway Trust Fund.” Then-Secretary Mary Peters told Congress that canceling the $631 million RABA increase would reduce the end-of-2009 shortfall to $238 million might “be a good start towards heading off the problem.”

In July 2007, the OMB Mid-Session Review showed the end-of-2009 Highway Account shortfall reaching $4.3 billion. Secretary Peters testified before the House Budget Committee at a hearing three months later that:

…the sustainability of the trust fund is indeed in serious jeopardy. And because we are spending so much more than we are taking in, we believe that we will have a deficit according to the mid-session review of as much as $4.3 billion by 2009. That is something that we are all going to have to work at together.

In fact, when the Administration submitted our 2008 budget, we proposed a budget that would have addressed the federal fund deficit at that time. And we proposed that we not allocate the RABA dollars. We proposed that spending restraint and prioritization be implemented.

The appropriators, unfortunately, not only ignored our proposal, which would have withheld some monies, but they added a billion dollars for bridge repairs, and they also added several billion dollars in earmarks to what has been passed to date. So we do have very serious concerns about the fund balance.

-Transportation Secretary Mary Peters, October 25, 2007

Rather than cut spending, the natural reaction of highway supporters on Capitol Hill was to simply take money from somewhere else to prop up the Trust Fund. In September 2007, the Senate Finance Committee approved a bill (S. 2345, 110th Congress) that was supposed to serve as the tax title for the pending FAA reauthorization, but that legislation also included several Highway Trust Fund revenue provisions, including a $3.4 billion transfer from the general fund supposedly justified by prior year appropriations of emergency relief highway funding, authorized by law, from the Trust Fund (as well as other provisions designed to add another $1.8 billion to the Trust Fund). The Finance legislation also contained a number of other non-FAA provisions, and the cumulative weight of all those drew a Republican filibuster of the entire FAA bill, which was then pulled from Senate consideration.

In its final budget request, in February 2008 (for fiscal 2009), the Bush Administration forecast an end-of-2009 Highway Account deficit of $3.1 billion and proposed to allow the Highway Account to be able to borrow funds as necessary during FY 2009 from the Mass Transit Account as a “non-interest bearing repayable advance.” This naturally was met with howls of outrage from the mass transit lobby who demanded that Congress come up with an “appropriate fix for the highway account shortage” without suggesting what that fix should be. The Appropriations Committees rejected this proposal out of hand.

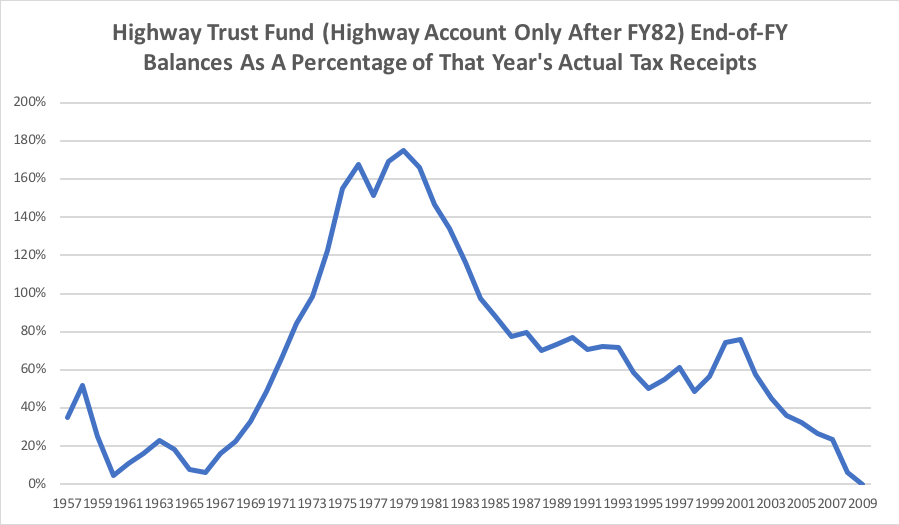

Tax committee leaders then decided in June 2008 to attach an $8 billion Highway Trust Fund bailout to the next short-term FAA extension bill, this one justified by the fact that the TEA21 law that created RABA and special budget treatment for the Trust Fund had, in exchange, written off $8.0 billion in existing balances. Those balances had all come from interest – the general fund paid the HTF (the Highway Account only after 1982) $22 billion in interest over the FY 1957-1998 period, and of that, $8 billion had been written off at the beginning of FY 1999. Most of that interest had been accumulated during the era of double-digit interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s. (This had peaked in FY 1981, when one dollar in every seven dollars of Trust Fund receipts came from interest payments on balances, not actual tax collections.)

Of course, interest payments from the general fund to a trust fund account are not the same thing as actual user tax collections. Not nearly.

(Ed. Note. Here’s an intellectual exercise: say I give you a $100 bill and you put it in your wallet. Then you take the money out of your wallet and put it in your left front pants pocket. You go about your daily business. At the end of the day, you take the $100 out of your left front pants pocket and put it back in your wallet. At that point, does your left front pants pocket owe your wallet interest for having held that $100 all day? And if so, where would your left front pants pocket get the money to pay that interest? Federal trust fund accounts exist only as a visibility exercise to make it clear the extent to which certain payroll or excise tax receipts correlate to spending for certain programs. Arguments that one Treasury account owes real money to another Treasury account just because money was moved from one account to another for a certain period of time have always seemed specious to this author.)

The House brought up the FAA extension on June 24, 2008. As originally introduced, the bill contained the $8.0 billion Trust Fund bailout. But the ranking Republicans on the Appropriations and Budget Committees, Jerry Lewis (R-CA) and Paul Ryan (R-WI), sent a strong letter of opposition to the bailout that morning:

“This bill just exacerbates our transportation funding problem by using an $8 billion taxpayer-funded band-aid on the terminally ill Highway Trust Fund. We need real reform and practical solutions, not more buck passing,” Jerry Lewis said.

Added Paul Ryan: “Most American families are squeezing their budgets ever tighter to cover skyrocketing food and gas prices. They’re setting priorities, making trade-offs. Congress needs to fix the Highway Trust Fund by doing the same.”

-House Appropriations Committee (GOP) press release, June 24, 2008

So when the Ways and Means designee moved to suspend the rules and pass the bill later that day, his version of the bill dropped the Trust Fund bailout. (The bill then passed unanimously.) House leaders then decided to move their own stand-alone Trust Fund bailout bill (H.R. 6532, 110th Congress) to the floor on July 23, 2008. Paul Ryan sent out a staff memo condemning the bill (written by the late, great Stephen Sepp1) which somewhat sarcastically noted chairman Bud Shuster’s promise in May 2008 that, if gas tax receipts declined, highway spending would be reduced.

During floor debate on H.R. 6532, Ryan quoted Shuster again, then prophetically stated:

My fear is that this transfer will be just the start, that we will be back here for a fix in 2010 with a bigger shortfall because as CBO says, the highway trust fund has not just hit a temporary rough patch, it is permanent red ink going into the future. The current shortfall is between $1.4 billion and $3.3 billion, and then it gets bigger year after year, well over a $300 billion shortfall over the next 10 years. Undoubtedly, when we get updated numbers from CBO and OMB, the shortfall will get even bigger.

If highways are to continue to enjoy special budgetary status as trust-funded programs, then this general fund transfer should be offset or repaid.

-Paul Ryan, July 23, 2008

The White House issued a veto threat on behalf of President Bush, stating that “this bill is both a gimmick and a dangerous precedent that shifts costs from users to taxpayers at large. Moreover, the measure would unnecessarily increase the deficit and would place any hope of future, responsible constraints on highway spending in jeopardy.” Nevertheless, the House passed the bill by an overwhelming margin, 387 to 37.

Five days later, on July 28, the White House OMB issued the annual Mid-Session Review of the budget, and as part of that process, they provided Capitol Hill with updated Trust Fund estimates that showed the Highway Account would finish FY 2008 with a $4.3 billion positive balance. And soon after that, when cold winter hit, tax receipts would again begin to exceed spending during the winter months and allow the Highway Account to recharge until spring. The need for extra money in the Trust Fund was not immediate.

Secure in this knowledge, Congress adjourned for its usual five-week recess on Friday, August 1. The House and Senate were not due back for business until Monday, September 8.

Then suddenly. At 11:00 a.m. on Friday, September 5, 2008, the USDOT press office emailed reporters to inform them that Transportation Secretary Mary Peters would be hosting a conference call in two hours “to provide an update on the financial status of the Highway Account of the Highway Trust Fund.”

During that call, Peters told the press that the OMB Mid-Session Review numbers had been based on estimated receipt and outlay numbers for June, July and August. But when the actual numbers came in, Highway Account tax receipts were $3.1 billion below those OMB estimates. So that took the projected year-end Highway Account balance down from $4.3 billion to $1.2 billion.

But then Peters laid out two cold, hard facts:

- The projected end-of-fiscal-year Trust Fund balances always include a large payment made by the general fund to the Trust Fund in mid-October to cover estimated excise taxes collected in the last two weeks of September. The money is then retroactively credited to the Trust Fund for the prior fiscal year. But money you will get in mid-October doesn’t do much good when you are trying to pay bills in late September.

- Even more urgently, transfers of estimated excise tax receipts from the general fund were only made twice a month per Treasury policy, and the next scheduled transfer date was September 11. At the close of business the day before (Thursday, September 4), Peters said that the Highway Account only had about $343 million in the bank. At that time of year, the usual rate of reimbursement to state DOTs was in the $220-240 million per day range. This meant that the Highway Account was almost certain to run out of cash on Monday, September 8.

Accordingly, Peters said that FHWA was suspending the regularly scheduled twice-daily electronic reimbursements to state governments, effective first thing on Monday, and said that states would have to wait four days for repayment. The biweekly transfer due on the 11th would be between $1 billion and $1.4 billion – together with the $252 million that wound being left over at the end of the day last Friday, that total would be enough to pay all states 100 percent of the amount owed them to date.

FHWA also arranged with the Treasury to make future transfers from the general fund weekly rather than biweekly and said that future reimbursements would be made once a week to states based on available cash.

But weekly transfers would only be half the size of biweekly transfers, and if the situation continued, it was likely that there wouldn’t be enough cash in the Highway Account on September 18 to pay states 100 percent of what they were owed — in which case FHWA had determined that all states would then receive a pro-rated amount of their pending reimbursement claims based on however much money was left in the Highway Account.

Peters also announced that because of the urgency of the situation, she had reversed her earlier position and was recommending that the President sign the House-passed $8 billion bailout legislation.

As a result, the full might of the state governments and construction industry/labor union alliance was turned on the Senate to get them to approve the bailout bill as soon as possible. When the Senate returned on September 8, Majority Leader Reid started trying to bring up the House-passed bill. Budget Committee rankin member Judd Gregg (R-NH) held it up because he wanted to be able to get a vote on an amendment reinstating the Byrd Test, and the next day, noted earmark critic Tom Coburn (R-OK) also objected because he wanted to get a vote on an amendment to make sure that the $8 billion bailout wasn’t spent on bike trails, parking lots, museums, and other enhancements.

Reid, for his part, kept asking that GOP presidential nominee John McCain come off the campaign trail and come back to the Senate to discuss the issue (knowing full well that McCain had always been a major opponent of the highway lobby, had been one of the four votes against SAFETEA-LU, and that McCain’s natural instincts would be to do and say things that would irritate all state governments). (Ed. Note: People forget that McCain and Hillary Clinton both endorsed a temporary repeal of the entire gasoline tax in April 2008 as a way of easing the financial burden on drivers during the summer months, so obviously Trust Fund solvency was not high on their priority lists.) Reid refused to allow any amendments, and pressure from their colleagues and the state governments led Gregg and Coburn to relent and allow H.R. 6532 to pass on September 10 without a recorded vote.

Part 3 – Going Forward, the Path of Least Resistance

Aftermath. The $8 billion bailout (amended by the Senate to take effect immediately instead of on October 1) was signed into law by President Bush on September 15, 2008 and fixed the insolvency problem long enough to get well into 2009. The pending Presidential election precluded any other substantive legislation in the remainder of 2008.

Even though SAFETEA-LU was scheduled to expire on September 30, which made reauthorization an imminent concern, the Great Recession took priority. Congress started off with the ARRA stimulus bill and then quickly turned its attention towards health care reform, financial regulation, and greenhouse gas emission restrictions. House T&I chairman Jim Oberstar (D-MN) thought that surface transportation reauthorization was an ideal candidate to be part of the economic reform agenda, and had prepared a draft bill predicated on a motor fuels tax increase, but as he had the press waiting in a hearing room for him to outline the bill in June 2009, new Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood went to the Rayburn Building to tell him that the Obama Administration wanted an 18-month extension of SAFETEA-LU instead (with another bailout). The White House wanted the transportation bill to be dealt with by the following Congress.

Oberstar hit the roof (this author saw him about 10 minutes later, still visibly outraged), but Obama had Speaker Pelosi and Ways and Means Chairman Rangel on his side, so no reauthorization legislation was possible in that Congress. Instead, another $7 billion general fund bailout was enacted in August 2009, followed by a $19.5 billion bailout (this one also including the Mass Transit Account) in March 2010.

As for those vaunted blue-ribbon panels that were supposed to recommend paths for long-term solvency for the Trust Fund: the Policy and Revenue Study Commission’s final report (December 2007) recommended that “the Federal fuel tax be increased from 5 to 8 cents per gallon per year over the next 5 years, after which it should [be] indexed to inflation.” The Financing Commission’s final report (February 2009) recommended that “Given the significant current funding shortfall, the Commission concluded that the best near-term options for federal investment are increases to current federal fuel taxes and other existing HTF revenue sources.”

But it turned out that President Obama was no more willing to countenance a gas tax increase than President Bush had been (at least at first), and Democratic leaders in Congress were unwilling to force his hand. As Secretary LaHood said in June 2009: “The Administration opposes a gas tax increase during this challenging, recessionary period, which has hit consumers and businesses hard across our country.”

Both blue-ribbon panels also recommended a gradual shift from a gallons-based fuel tax to an eventual vehicle miles-traveled (VMT) tax as a way of keeping the user-pay, user-benefit principle of the Trust Fund viable in decades to come. When the Financing Commission handed in its report, LaHood said he was taking the VMT proposal seriously. But on February 20, 2009, the White House press secretary stated flatly that a VMT fee “is not and will not be the policy of the Obama administration.” (Momentum for a VMT fee still has not recovered from that day.)

President Obama’s hopes for enacting his own surface transportation bill as a legacy achievement in 2012 was upended by the Republican takeover of Congress in the 2010 elections, which put a possible gas tax increase even farther away. Eventually, the two-year MAP-21 law was paid for by more general fund transfers instead of real user revenue increases, and the annual Trust Fund cash deficits grew deeper, which made the size of any workable user tax revenue increase even larger and more politically unrealistic. This culminated in the massive $70 billion Trust Fund bailout to enable the five-year FAST Act of 2015.

(Thanks to Ryan’s efforts as Budget chairman, the 2012-2015 bailouts had most of their cost offset over a ten-year period, albeit with sometimes illusory or fanciful “pay-fors” that may or may not ever materialize in fact.)

What have we learned? The Highway Trust Fund’s insolvency, and the events which led to it, suggest a few takeaways.

Revenue estimates are just that – don’t trust them too much. The authors of SAFETEA-LU put the Trust Fund on a “glide path” to insolvency by the year 2010, but the bill was finalized just weeks before Hurricane Katrina hit. Katrina caused a spike in gas prices up to $4 a gallon in many places, which for the first time threatened the inelasticity of gasoline demand and either caused or coincided with a downturn in the market for gas-guzzling SUVs and a decrease in total miles traveled. Tax revenue estimates a year or two in advance should always be considered educated guesses at best and estimates farther out than that should be considered WAGs (wild-assed guesses). If the Trust Fund can ever be put back on a sound user-pay footing (a big “if”), any attempt to tie spending levels to taxes must only use actual tax receipts already collected – not estimates of future tax receipts.

The best way way to hold back unsustainable spending is to prevent the money from being provided in the first place. Looking back, the most fateful decision point in the Trust Fund’s decline was the decision in fiscal 2003 not just to cancel the “negative RABA” adjustment that would have pushed 2003 highway funding well below the $27.7 billion level originally promised by SAFETEA-LU, but to instead go ahead and keep funding highways at the unsustainable $31.8 billion level that had been provided in 2002 due to faulty revenue estimates. In a program where stakeholder groups are this powerful, history has now proven that spending is usually a ratchet that can only move upwards. Since every spending increase is apparently perpetual and irrevocable, any spending increase should be carefully considered, particularly if such an increase is not sustainable in the long term.

Trust funds need sizable “rainy day” balances. Just because a trust fund account has a sizable cash balance does not mean that it is safe to plan on “spending down” that balance to near-zero levels, as SAFETEA-LU did. The Highway Account balances that Congress decided to “spend down” in 2005 were about 30 percent of a year’s tax receipts – not much by historical standards.

FHWA used to say that Congress should never plan on leaving the Trust Fund with less than three months worth of outlays at any one time, because sudden fluctuations in receipts and outlays can cause that financial picture to change quickly. This is exactly what happened in the summer of 2008. At some point, this changed so that FHWA only insisted on having $4-5 billion as a projected year-end balance, but this is well under three months worth of outlays. At current spending levels, a three-month outlay safety margin would be $11 billion for the Highway Account and a little over $2 billion for the Mass Transit Account.

Place not your faith in blue-ribbon panels. The authors of SAFETEA-LU thought that the report of a blue-ribbon panel of experts (or better yet, two panels of experts) might give Congress political cover for making politically uncomfortable revenue decisions. This was a time-honored Washington tradition. The Greenspan Commission on Social Security reform in 1983 is the gold standard in this regard. This author has done a lot of research on the Hoover Commissions in the 1940s and 1950s that had a lot to do with shaping the structure of federal transportation policy. And of course the entire setup of today’s Department of Homeland Security (good and bad) has a lot to do with the report of the 9/11 Commission. But the two surface transportation commissions were unable to move the public opinion needle on a gas tax increase – it may have something to do with the role gasoline consumption plays in the daily lives of average Americans, but whatever the reasons, the commission reports didn’t convince Congress to increase taxes.

Don’t believe that future generations of politicians will have courage that you lack. Unable to get their President or their colleagues to agree to a gas tax increase, the authors of SAFETEA-LU decided to spend Trust Fund money as if a gas tax increase was going to be enacted three or four years down the line. The hope was that the next set of committee chairmen and party leaders, and the next president, would be able to raise gas taxes where they could not. This did not happen. Fiscal responsibility, at least in the last few years in Congress and the Administration, is on the decline, not the rise.

The Congressional Budget Office currently projects the Highway Trust Fund to run out of cash again in mid-2021, after the expiration of the FAST Act in September 2020. Current spending levels will require an average of $20 billion per year in additional bailouts, or revenue increases, every year thereafter. Forever.

1 As Sepp would have said at the time, bortaS bIr jablu’DI’ reH QaQqu’ nay’