Part of an ongoing series documenting attempts to centralize the organization of federal responsibilities for transportation:

The only public statement ever made by the Eisenhower Administration regarding the creation of a Cabinet-level Department of Transportation was one sentence on page M18 of his final budget message to Congress in January 1961: “a Department of Transportation should be established so as to bring together at a Cabinet level the presently fragmented Federal functions regarding transportation activities.”[1] This endorsement was cited by Lyndon Johnson in his own 1966 message to Congress proposing creation of a DOT.[2]

However, President Eisenhower came much closer to creating a Department of Transportation than was publicly known, then or now. Documents at the Eisenhower Library reveal just how close the Eisenhower Administration came to doing so, under the behind-the-scenes leadership of the President’s most trusted advisor – his brother, Milton.

Milton Eisenhower and PACGO.

There were seven Eisenhower boys born to David and Ida Eisenhower, six of whom lived to adulthood. Dwight D. was the thirdborn, and Milton S. was the youngest, almost nine years younger than the future President. The other boys were star athletes, but a childhood bout of scarlet fever had left Milton weaker than the rest. He was a boy reporter for the local Abilene newspaper while still in high school and worked his way through Kansas State University to get a journalism degree, and was appointed to the university faculty to teach journalism immediately afterwards.[3]

After an interregnum in the State Department (in the U.S. consulate in Edinburgh), President Coolidge appointed Milton Eisenhower’s mentor, the President of Kansas State University, to be Secretary of Agriculture, which caused Milton to join USDA as head of public affairs and information. Eisenhower stayed at Agriculture through the Hoover Administration and then, under Franklin Roosevelt and Secretary Henry Wallace, got promoted and became a New Deal spokesman and a confidant and troubleshooter for both Wallace and Roosevelt.

Then, in March 1942, Roosevelt abruptly put Milton Eisenhower in charge of relocating Japanese citizens and Americans of Japanese ancestry away from the West Coast. Eisenhower did the job for as long as he could stomach (three months) before resigning and then becoming head of the Office of War Information.

Milton left government in May 1943 to become the new President of his alma mater, Kansas State University. In 1950, he would leave Kansas State to take over as President of Penn State.

President Eisenhower was a strong believer in his younger brother. The President wrote a confidential letter to his best friend from high school, Swede Hazlett, in December 1953 saying “the man who, from the standpoint of knowledge of human and governmental affairs, persuasiveness in speech and dedication to our country, would make the best President I can think of is my younger brother, Milton. Under no circumstances would I ever say this publicly because, in the first place, I do not think he is physically strong enough to take the beating. In the second place, any effort to make him the candidate in 1956 would properly be resented by our people.”[4]

Milton had long been interested in government organization. Under Roosevelt and Truman, government organization proposals were strictly the domain of the Bureau of the Budget. But Dwight Eisenhower wanted an outside view.

On November 30, 1952, an Eisenhower transition spokesman made it official: the President would establish a President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization, to be chaired by Nelson Rockefeller, who at that point had held several Latin America foreign policy coordinating jobs under Roosevelt and Truman (in addition to running several family businesses).[5] The other two members would be Milton Eisenhower and Arthur S. Flemming, a member of the “Hoover Commission” on government organization in 1949 and President of Ohio Wesleyan University, who had been good friends with Milton Eisenhower since 1927.

The very first Executive Order of the Eisenhower Presidency (EO 10432), on January 24, 1953 created the Committee, which would become known as PACGO, and gave it the duty to “advise the President, the Assistant to the President, and the Director of the Bureau of the Budget with respect to changes in the organization and activities of the executive branch of the Government which, in its opinion, would promote economy and efficiency in the operations of that branch.”[6]

Flemming later recounted that President-Elect Eisenhower had told him “that he would from time to time want to try out ideas on the committee; that he also expected us to try out ideas on him. He urged us at that time to make immediate contact with members of his cabinet and talk with them about their ideas, get their ideas, and see what we could do about coming up with plans designed to implement their ideas.”[7]

Rockefeller said in an oral history interview that the three PACGO members never made a recommendation to President Eisenhower unless the three of them were unanimously in support of the proposal.[8]

PACGO’s first priority was to fulfill an Eisenhower campaign promise convert the Federal Security Agency into a Cabinet-level Department of Health, Education and Welfare. This first required Congress to extend the Reorganization Act of 1949 (which they did in a law signed February 11, 1953 (67 Stat. 4)). The HEW creation document was submitted to Congress via a reorganization plan on March 12, 1953 and became effective on June 20 of that year.

On April 22, 1953, Rockefeller met with the President, gave him copies of all the reports, and recommended that PACGO be closed down, allowing the Budget Bureau to implement the recommendations. President Eisenhower refused to accept the resignations and ordered PACGO to continue its work, albeit at a more relaxed pace.[9] (Rockefeller would soon be made Under Secretary of the new HEW, and Flemming was made head of the Office of Defense Mobilization (then a Cabinet-level post), so after the first few months of the Administration, PACGO became more of a part-time duty for its members for the remainder of Eisenhower’s presidency.)

President Eisenhower only submitted ten reorganization plans to Congress in his first year, all by June 1. The last one of these was the only one pertaining to transportation – Plan No. 10, submitted on June 1, simply transferred the funding responsibility for airline subsidies from the Post Office to the Civil Aeronautics Board (which was already the entity determining what the subsidy levels should be). The plan went into effect on October 1, 1953.

Another reason PACGO was going to slow down its activities was because Congress was in the process of creating more public panels on reorganization. A second blue-ribbon “Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of Government” (which would be, like the first such panel in 1949, chaired by former President Herbert Hoover) was created by a law enacted on July 10, 1953 (67 Stat. 142). The 12-member panel to “study and investigate the present organization and methods of operation” of the executive branch and was charged with reporting back recommendations for change by May 31, 1955.

The same day as the law creating Hoover II was signed, the President also signed another bill into law (67 Stat. 145) creating a 25-member Commission on Intergovernmental Relations “to study the proper role of the Federal Government in relation to the States and their political subdivisions, with respect to such fields, to the end that these relations may be clearly defined and the functions concerned may be allocated to their proper jurisdiction.”

On July 21, 1953, President Eisenhower met with Hoover to discuss his work plan for the second Hoover Commission and found that Hoover was “delighted with the opportunity to get back into the middle of this big problem. However, I was a bit nonplused to find that the only individuals he wanted on the Commission were those whom he knew shared his general convictions–convictions that many of our people would consider a trifle on the motheaten side. As quickly as I found this out, I tried to make my other three appointments from among individuals whom I knew to be reasonably liberal or what I call middle-of-the-road in their approach to today’s problems.”[10]

One of those presidential appointees to the second Hoover Commission was Arthur Flemming, who had served on the first Hoover Commission and who would also be able to keep PACGO apprised of the second Commission’s progress.

In a later diary entry, President Eisenhower wrote that “I personally doubt the need for the [Second Hoover Commission], because of the simultaneous authorization of another Commission [the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations] which will have to do with the division of functions, duties and responsibilities between the federal government and the several states. It seems to me that this second Commission, in order to reach its answers, will have to cover almost the identical ground that the Organizational Committee will. Essential functions of the federal government can be specified and segregated only in the light of what it is proper for states to do. Nevertheless, and in spite of the fact that these views were carefully explained to Congressional leaders, two or three individuals on the Hill were so determined to have a new ‘Hoover’ Commission that I had to accept the Hoover Commission in order to achieve the other one, from which I expect much.”[11]

Creating a Cabinet Committee.

On March 1, 1954, Milton Eisenhower wrote separately to Nelson Rockefeller and to Arthur Kimball, the head staffer for PACGO, to suggest that the committee take up the issue of “the organization of transportation affairs, particularly as organization bears upon the ability of the Administration to develop a national transportation policy.” The impetus was Milton’s belief “that our railroads – once politically powerful and ruled by robber barons – are now getting close to collapse, unable to withstand the competition of the subsidized airplanes, trucks, busses, and ships.”[12]

PACGO had a regular meeting scheduled for March 5, where they discussed the idea. Flemming, as the head of ODM, realized that one of the country’s leading experts on federal transportation policy and organization was already an outside consultant to ODM, so PACGO commissioned a background statement and analysis of the problems from him. The man was, of course, Ernie Williams, who had been the chief proponent of the “Federal Transportation Agency” concept that President Truman almost proposed in 1946 and who was now a professor at the business school at Columbia University.[13]

Williams quickly responded with a nine-page single-spaced memo entitled “Transport Policy and Organization” which continued the themes he had been sounding since 1946. After pointing out the many deficiencies and inconsistencies in both federal promotional policy and federal regulatory policy, he recommended that all promotion of transportation be centralized in one place, with authority to consolidate railroads, integrate transport across modes, set route patterns, with a consistent national system as the primary goal. Williams said that the new entity would have to develop a new type of employee qualified to compare competing modes. But he did not make a clear recommendation as to whether a Cabinet-level DOT, a beefed-up transportation service within Commerce, or an independent sub-Cabinet agency was better.[14]

(The career staff in the Office of Transportation at the Commerce Department had already been thinking along the lines of the “beefed-up transportation service within Commerce” lines – at the start of the Eisenhower Administration, in February and March 1953, the staff had assembled a confidential wish list of federal transportation responsibilities outside Commerce that could possibly be transferred to Commerce. These included the Coast Guard, the safety regulation and car service functions of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the safety regulation and general air carrier subsidy functions of the Civil Aeronautics Board, and other miscellaneous functions. But apparently nothing came of this during the 1953-1954 period.[15])

Williams’ memo closed by suggesting that a Cabinet Committee be convened to study the subject. By mid-April, Rockefeller and Milton Eisenhower had agreed on a two-page memo to President Eisenhower, to be signed by both Rockefeller and Budget Director Rowland Hughes, recommending that the President create “A cabinet committee consisting of the Director of the Office of Defense Mobilization [who, remember, was also a PACGO member] and the Secretaries of Defense and Commerce…to explore and formulate policy and organizational recommendations covering the whole field of transportation.”[16]

The three PACGO members, along with Budget Director Hughes and White House chief of staff Sherman Adams, had lunch with the President on May 3 to brief him on their work. They got the go-ahead, but since the President wanted his Cabinet to be an integral part of the decisionmaking process, the matter was put on the agenda for the May 14 Cabinet meeting. Sherman Adams sent all Cabinet members a two-page summary memo pointing out how important transportation was and that “Organizational aspects cannot be separated from policy considerations…Present organization does not permit focusing of responsibility for policy formulation on any one Cabinet Member.” The official recommendation was “Establish a Cabinet Committee to Explore and formulate overall policy and organizational recommendations covering the whole field of transportation.”[17]

The minutes of that Cabinet meeting show that the recommendation was approved, though with some uncertainty about how the Cabinet Committee would be staffed. (Also, Commerce Secretary Sinclair Weeks “interpreted the recommendation as an effort to tie in certain of the activities of the independent agencies with the existing transportation structure in the Department of Commerce.”)[18] But it was decided that the public announcement would be held for a later date.

That did not happen until July 12, when the President signed a letter to Secretary Weeks (drafted by PACGO and released to the public by the White House press office) establishing the Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization, naming Weeks the chairman, and asking for a report by December 1, 1954. The President’s letter was specific that “the organization of the Federal Government to cope with transportation problems should be reviewed.”[19]

(July 12, 1954 was also the same day when Vice President Nixon delivered the President’s speech proposing a $50 billion highway program to the Governors’ Conference in upstate New York. The President was unable to attend the conference because Milton’s wife had passed away and her funeral was the following morning in State College, Pennsylvania.)

The Cabinet Committee goes awry.

Chief of Staff Sherman Adams sent Weeks a two-page memo on July 14 outlining what he thought the scope of the Cabinet Committee’s work should be, including “Recommendations for organizational changes in the Government structure” needed to accomplish the policy objectives of the report.[20] Hearing nothing back, Adams wrote Weeks again a month later, asking for “periodic progress reports, perhaps every two weeks.”[21]

Weeks responded to Adams on August 20, telling him that he had appointed a study group of experts, led by Arthur W. Page of AT&T, and including other business leaders but also including Charles Dearing of the Brookings Institution (who had written the recommendation for a DOT for the Hoover Commission’s Task Force on Transportation) and Ernie Williams himself, which had met the day before.[22]

It was at this point that things started to go badly wrong.

Ernie Williams reported back to PACGO (through staffer Jerry Kieffer) from the August 19 Cabinet Committee consultants meeting, saying that “the meeting was rather disorganized and no plan of action was discussed. All of the individuals concerned seemed to be part-time people, several of whom are unlikely to be able to spend much time with the project…Paige [sic] also told Williams that he would not put too much stock in following the format requested by the memo from Sherman Adams.”[23] Page told the group that Charles Dearing (who was absent) would be writing up some plans, but Williams later phoned Dearing to discover that no one had told Dearing any such thing.

A few days later, Williams told Flemming that “None of the staff persons so far collected seem to be aware of the origin and background of this Cabinet Committee and its mission” – which was called into being because of a memo that Williams himself had written for PACGO – “and Ernie has kept silent on his role. So far, the activity is very much a Commerce Department show.”[24]

Williams talked to PACGO staff again on September 13, with more bad news: “Nothing has been done to put these people to work…There is no parceling of work in the group…The concern is domestic surface transportation (nothing about air or shipping)…With such a late commencement to this operation, if we want to do something formidable, the December 1 date will have to be changed.”[25]

This finally got passed up the chain of command the following day, with Arthur Kimball sending Nelson Rockefeller a confidential memo summarizing the situation according to Williams, including that “Far from taking an over-all look at the whole problem of transportation policy and organization which our Committee and the President sought, the Page group appears to have limited its inquiry to the problems of the railroads vs. trucks.”[26]

Kimball met with Arthur Page and Charles Dearing at the end of that week, and they told Kimball that their work would focus only on surface transportation and would “Avoid organizational problems, i.e., Department of Transportation vs Commerce, single regulatory agency.” Dearing dismissed the idea of a DOT because there would be little left of Commerce: “93% of the Department of Commerce appropriation is transportation.”[27] They said they would propose such a limiting agenda at the next meeting of the Cabinet Committee, scheduled for October 7.

The members of PACGO decided that they wanted to meet with Secretary Weeks on the topic. During a prep session, PACGO staffer Arthur Kimball talked to Weeks, who “seemed surprised to learn that Messrs. Page and Dearing contemplated narrowing the study and indicated that his idea was to include aviation, railroads, trucking, barges, etc. but excluding only overseas aviation and the merchant marine.”[28] The PACGO members were scheduled to meet with Weeks on October 5 to ask him if he wanted an extension of the December 1 deadline in exchange from broadening the scope of the report, but we were unable to find any records of that meeting actually taking place.[29]

The Cabinet Committee met again on October 14, and Williams later told the PACGO staff that the draft report was confined to making partial deregulation of rail freight “in order to shore up the competitive position of the common carriers.” Per Williams, “Mr. Flemming asked whether the staff proposed to examine government transportation organization. Mr. Weeks replied he thought that their objective should be to reach substantial agreement on policy matters before examining organization. The Cabinet Committee did not, at any time during its meeting, discuss the subject of extending its work period or requesting a later reporting date or doing any more than the portion of its general assignment that was embodied in the draft report…”[30]

Flemming, a member of both PACGO and the Cabinet Committee, wrote to Weeks on November 2 urging that the Cabinet Committee also consider domestic aviation and coastwise and intercoastal water transportation, and adding that the “policy changes of the far reaching character contained in the staff report urgently require consideration of organization matters as called for by the directive of the President.”[31]

PACGO tried to go over Weeks’ head, writing to White House chief of staff Sherman Adams on November 9, attaching a copy of Flemming’s memo to Weeks and asking Adams to order the committee to extend its brief to the original request and work past the December 1 deadline.[32] Adams did send Weeks a memo on November 12 making it clear that “the President expects the Cabinet Committee to comply fully with the assignment which was set forth in his letter of July 12, 1954 and in my memorandum of July 14, 1954…I would appreciate early advice from you as to plans and timing for carrying out the remainder of your assignment, including Government organizational proposals.”[33]

Secretary Weeks responded to Adams on the evening of November 16:

- Regarding coastwise and inter-coastal water transport, “the Under Secretary for Transportation has had underway for some period a study of this particular activity which will be ready shortly after the first of the year.”

- Regarding domestic aviation, “your staff is not fully informed about this matter…Mr. Page’s working committee has reviewed the report on Civil Air Policy issued by the Air Coordinating Committee last May and approved by the President and their recommendations resulting from this review will, of course, be incorporated into our policy recommendations.”

- Regarding government reorganization: “subject to the wish of the Committee, which next meets on 22 November, it is the thought of the working group that the implied organizational changes are of such scope and nature that to do justice to this phase of the problem will require additional study. The decision on the degree and extent of organizational changes naturally hinges very largely on what action the Congress may or may not take with respect to our policy recommendations.”[34]

Flemming’s PACGO adviser Jerry Kieffer told Flemming that “If you go along with Mr. Weeks’ proposal to postpone organizational recommendations until the fate of the policy recommendations is known, the White House people will not get the relief through reorganization that they seek and think they need. The fate of the policy recommendations will not be known for six months to a year, and worse yet from the standpoint of the White House people, they must somehow review the policy recommendations due December 1 and advise the President on what he should accept or reject for possible submission to the Congress.”[35]

The draft report prepared by Page and his group of advisers (and largely written by Williams) said “Your Committee has not proposed any changes in the Federal organization for the administration of transportation functions and responsibilities. It is our belief that any necessary organizational adjustments should follow the revision of transportation policies to permit determination of required changes in the Federal structure for their most effective administration.”[36]

Aftermath.

The Cabinet Committee accepted the draft report on November 15, and it was transmitted to the White House as the report of the Cabinet Committee on December 7. For a summary of its policy recommendations, and what happened to them, see Federal Railroad Policy Under President Eisenhower by this author, but suffice it to say that it took three separate Cabinet meetings over four months before a watered-down version of the report was released to the public, not as an Administration proposal, nor as the report of a Cabinet Committee, but as the report of a “President’s Advisory Committee” and attributed in public to Weeks himself. (For a deeper dive into the policy, see “The Weeks Report: A Memoir,” a 1987 retrospective from Transportation Journal written by Williams himself.)

PACGO held a meeting on January 10, 1955, from which Flemming was absent. The staff sent Flemming a summary of the meeting, which noted that “When Mr. Rockefeller commented that the Cabinet Committee’s report is not the type of comprehensive examination of transportation contemplated by PACGO and the White House, Dr. Eisenhower guessed that we would have to wait for the ‘millennium’ for a fully comprehensive report.”[37]

Nelson Rockefeller then went on a long tangent about the growth rate of air transportation, a mode that had not even been mentioned in the Weeks report. The meeting concluded with Rockefeller and Milton Eisenhower washing their hands of the idea of a comprehensive transportation report, but thinking that “PACGO might take the lead in recommending a separate study of the impact of jet and other developments in aviation on transportation in general which needs far more attention than apparently it has received thus far.”[38]

See Federal Aviation Policy Under President Eisenhower by this author for the story of how this decision led almost immediately to PACGO retaining outside expert William Barclay Harding for an initial report on future aviation facilities needs, which led to the larger “Curtis report” on airways modernization, which (along with several high-profile fatal aviation accidents) led to the creation of an independent Federal Aviation Agency in 1958.

The Cabinet Committee going awry was also a learning experience for PACGO: “Mr. Rockefeller commented one lesson which should be obvious from our experience with the Cabinet Committees on Transport and Water is the need to establish independent staffs for such studies under White House auspices with continuing and effective White House liaison.”[39]

As for a large-scale reorganization of the transportation functions of the federal government, the failure of the Cabinet Committee and the new emphasis on aviation meant nothing else got going on the subject during President Eisenhower’s first term. And the second Hoover Commission also avoided the topic – while they did issue a report on transportation, in March 1955, it was confined to efficiencies in how the various federal agencies, principally Defense, spent their money on transportation. (Object class analysis, not functional analysis.)

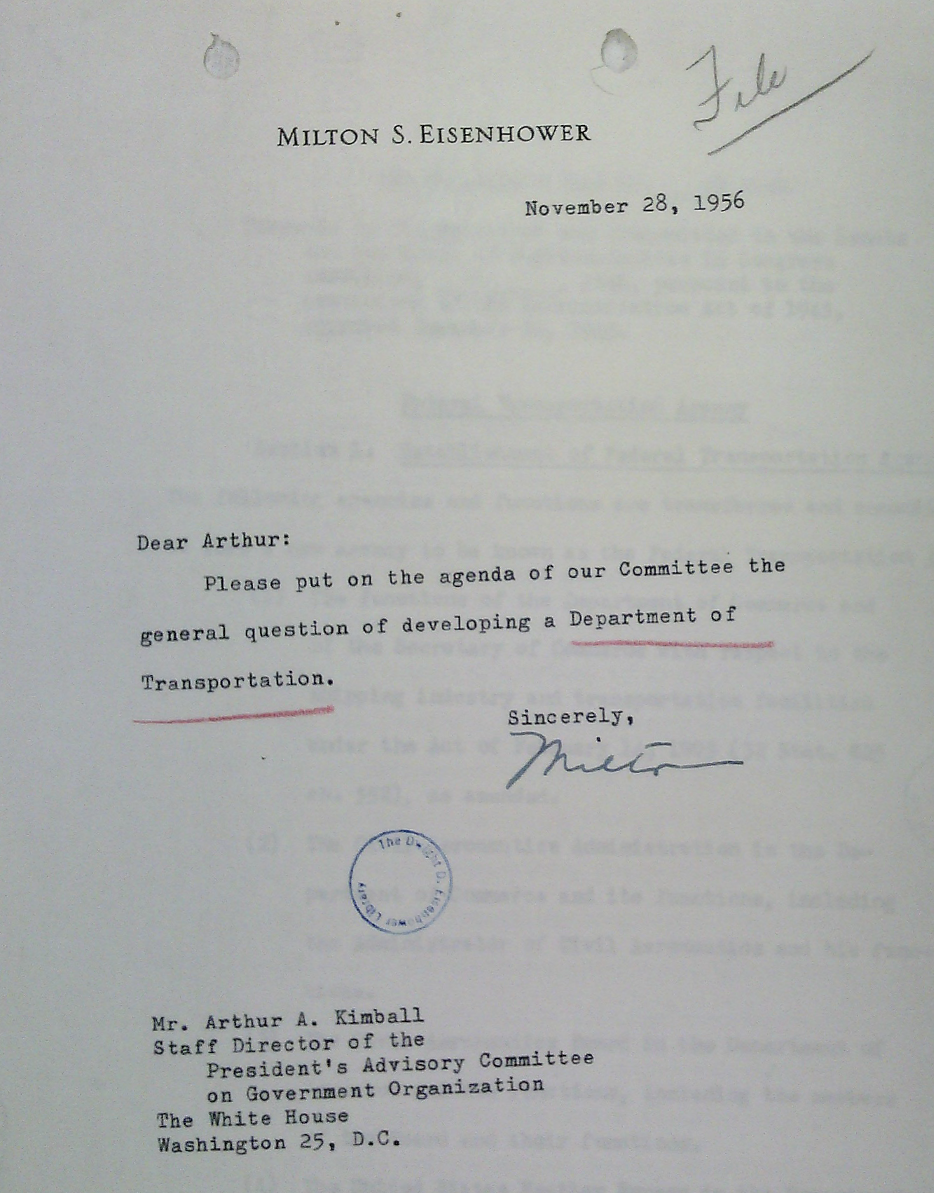

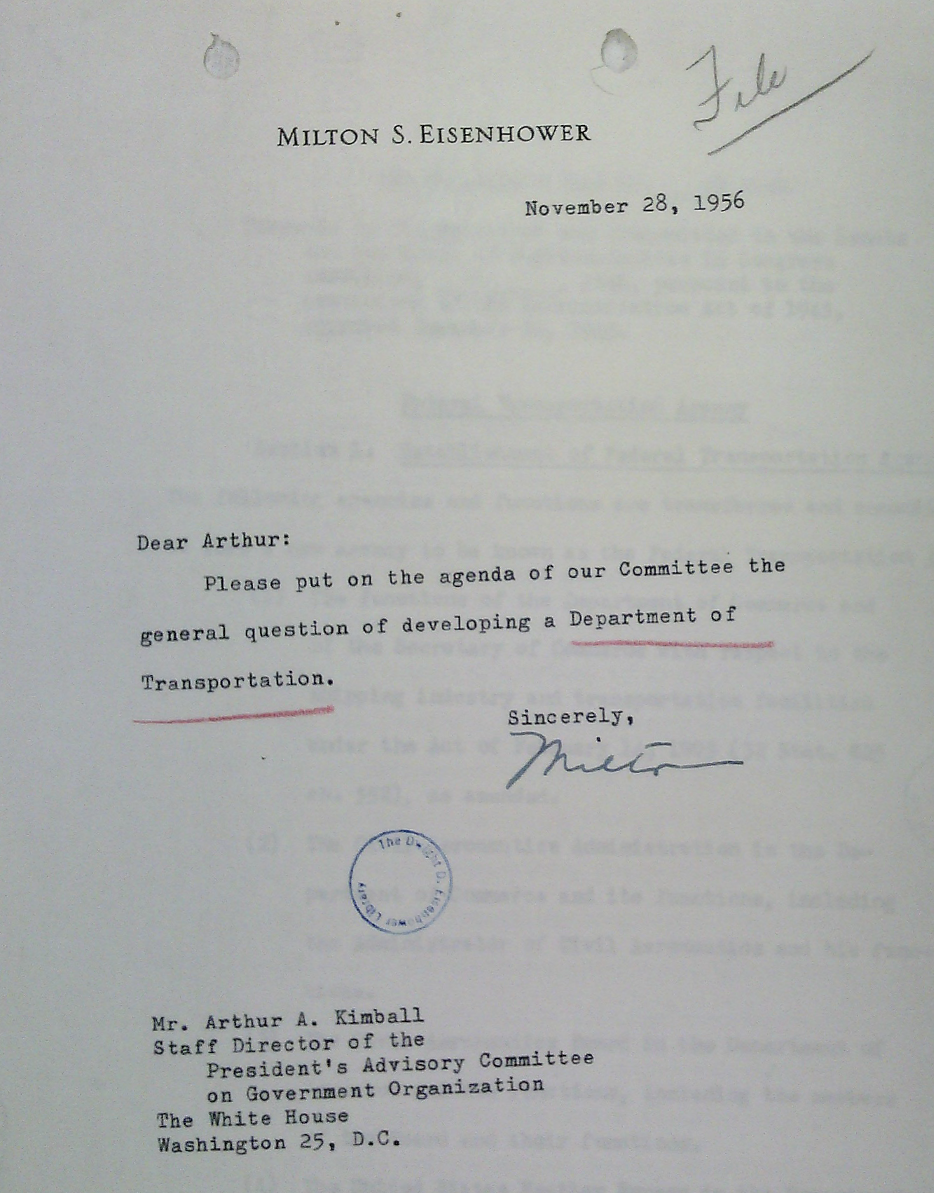

But, shortly after the President’s reelection, his brother decided to restart the process:

Attached to Milton’s one-sentence missive was a copy of the May 8, 1946 draft reorganization plan that Ernie Williams had written creating a Federal Transportation Agency. (Which is the only reason this author knew of that plan’s existence, and therefore the only reason he ever went to the National Archives to pull up the Bureau of the Budget’s records on the subject from the Truman Administration.)

Milton Eisenhower’s persistence on the subject would lead to a great deal of behind-the-scenes action on possible creation of a Department of Transportation throughout his brother’s second term.

To be continued…

[1] Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Budget Message of the President,” in The Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1962. Washington: GPO, 1961 p. M18.

[2] Lyndon B. Johnson, Special Message to the Congress on Transportation, March 2, 1966. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Lyndon Johnson, 1966, as document 98 starting on page 250 (reference is on page 253).

[3] In general, for Milton Eisenhower’s story in his own words, see his book The President Is Calling (New York: Doubleday, 1974), from which the main points of this biographical summary are taken.

[4] Dwight D. Eisenhower, letter to Edward Everett Hazlett, Jr., December 24, 1953. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Louis Galambos and Daun van Ee, eds.), volume XV, item #640 on p. 788 (quotation is from p. 792). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

[5] William R. Conklin, “Eisenhower Selects Aldrich To Be Ambassador to Britain; Nelson Rockefeller Heads Group to Study Reforms in Executive Branch.” The New York Times, December 1, 1952, p. 1.

[6] Federal Register, January 29, 1953, p. 617.

[7] Oral history interview with Arthur S. Flemming (OH #506), November 24, 1978, for Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, p. 3. Retrieved online on July 21, 2021 at https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/oral-histories/oral-history-transcripts/flemming-arthur-506.pdf

[8] Oral history interview with Nelson A. Rockefeller (OH #231), August 16, 1967, for the Columbia Uniersity Oral History Project, p. 23. Original located in Eisenhower Library.

[9] Dwight D. Eisenhower, letter to Nelson Rockefeller, April 23, 1953. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Louis Galambos and Daun van Ee, eds.), volume XIV, item #155 on p. 177. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

[10] Dwight D. Eisenhower, diary entry, July 24, 1953. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Louis Galambos and Daun van Ee, eds.), volume XIV, item #341 on p. 417 (quotation is from pp. 418-419). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

[11] Ibid (quotation is from p. 420).

[12] Letter from Milton S. Eisenhower to Arthur Kimball, March 1, 1954. Original (along with related letter from ME to Nelson Rockefeller on the same date) located in U.S. President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization: Records, 1953-1961 collection, Box 21, folder entitled “No. 175 – Transport policy and coordination 1954-1956 (See Transportation activities 1957-1960),” Eisenhower Library (hereinafter PACGO 175).

[13] March 5 meeting recounted in a memo from Arthur A. Kimball to the PACGO members, March 18, 1954, subject “Transport Policy and Organization.” PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[14] Memo from Jerry Kieffer to Arthur S. Flemming, subject line “Transportation Policy and Organization (Summary of Statement Prepared by Ernie Williams),” March 29, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[15] Memorandum from Paul Royster (Director, Office of Transportation) to Ray Kirener (Deputy Under Secretary), subject line “Recommendations Concerning Federal Transportation Activities Being Considered for Transfer to the Department of Commerce,” March 5, 1953. Original located in Records of the Department of Commerce (RG 040), Office of the Under Secretary for Transportation, Entry A1 26 General Records, 1955-1963, Container 12, folder entitled “President’s Committee on Government Organization (Flemming Committee) 1959,” National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[16] Draft memo from Nelson Rockefeller and Rowland Hughes to President Eisenhower, subject line “Transport Policy and Organization,” undated but with a cover letter dated April 19, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[17] Memo from Sherman Adams to the Cabinet, subject line “Transport Policy and Organization,” dated May 12, 1954. Original located in Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Papers as President of the United States, 1963-1961 (Ann Whitman File), Cabinet Series, Box 3, Folder entitled “Cabinet Meeting of May 14, 1954,” Eisenhower Library.

[18] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Minutes of Cabinet Meeting, May 14, 1954” p. 5. Original located in Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Papers as President of the United States, 1963-1961 (Ann Whitman File), Cabinet Series, Box 3, Folder entitled “Cabinet Meeting of May 14, 1954,” Eisenhower Library.

[19] Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Letter to Secretary Weeks Establishing a Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization,” July 12, 1954. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1954, as document 163 starting on page 627.

[20] Memo from Sherman Adams to Sinclair Weeks (no subject line), July 14, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[21] Memo from Sherman Adams to Sinclair Weeks (no subject line), August 13, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[22] Memo from Sinclair Weeks to Sherman Adams (no subject line), August 20, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[23] Memo from Jerry Kieffer to Arthur A. Kimball, subject line “Status of Organization of Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization,” August 24, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[24] Memo from Jerry Kieffer to Arthur S. Flemming, subject line “Status of Organization of Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization – Role of Ernie Williams,” August 26, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[25] Unsigned memo entitled “Notes on conversation with Ernie Williams,” September 13, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[26] Memo from Arthur A. Kimball to Nelson Rockefeller, subject line “Transport Policy and Organization Informal Discussion with Ernie Williams,” September 14, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[27] Unsigned memo entitled “Meeting with Messrs. Page and Dearing,” September 17, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[28] Memo from Arthur Kimball to PACGO members, subject line “Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization,” September 21, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[29] Meeting scheduled in a letter from Nelson Rockefeller to Sinclair Weeks, September 23, 1954, and agenda in unsigned “Notes for Discussion with Chairman of Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization,” both PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[30] Unsigned file memorandum, subject line “Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization – Notes on Discussion with Ernie Williams, October 29, 1954,” dated November 1, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[31] Memo from Arthur Flemming to Sinclair Weeks, subject line “Cabinet Committee on Transportation Policy and Organization,” November 2, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[32] Memo from Nelson Rockefeller to Sherman Adams, subject line “Transport Policy and Organization,” November 9, 1954. PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[33] Memo from Sherman Adams to Sinclair Weeks, no subject line, November 12, 1954. Copy located in PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[34] Memo from Sinclair Weeks to Sherman Adams, no subject line, November 15, 1954. Copy located in PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[35] Memo from Jerry Kieffer to Arthur Flemming, subject line “Transport Policy and Organization,” November 22, 1954. Copy located in PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[36] Revision of Federal Transportation Policy: A Report to the Secretary of Commerce, Chairman, Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization, From the Working Group, November 15, 1954 p. 29. Copy located in PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[37] Memo from Arthur Kimball and Jerry Kieffer to Arthur Flemming, subject line “Report of the Cabinet Committee on Transport Policy and Organization,” January 12, 1955. Copy located in PACGO 175, Eisenhower Library.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.