April 9, 2019

Part 1 of this series described plans for the reorganization of federal transportation and public works activities under the Harding, Coolidge, Hoover and Roosevelt Administrations. The predominant attitude during that time was that all federal public works activities were basically the same and should be grouped together as a Department of Public Works. Franklin Roosevelt used reorganization authority given him by Congress in 1939 to create a Federal Works Agency that included the Public Roads Administration, the Housing Authority, the various public buildings agencies, and the New Deal public works agencies (WPA and PWA) which were, at the time, the sole source of federal aid to civilian airports.

Transportation, by contrast, was thought of solely as an activity that was occasionally carried out using a public work, and it was viewed as a subset of the federal role in interstate and foreign commerce, concentrated at the Commerce Department.

Harry Truman takes charge.

Harry S. Truman became President of the United States upon the sudden death of his predecessor on April 12, 1945. The opening days of his Administration were naturally preoccupied with getting up to speed on World War II, but after the unconditional surrender of Germany on May 8, eventual victory in the war with Japan seemed certain – it was only a matter of time and effort.

The prospect of the end of the war forced Truman’s hand in the field of government reorganization. Days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Congress passed, and President Roosevelt signed, the First War Powers Act, 1941 (55 Stat. 838). Title I of that law was based on similar power given to Woodrow Wilson at the start of World War I and gave the President near-plenary power to reorganize the functions and offices of government – temporarily. (Only the General Accounting Office was exempted from the reorganization authority.) But six months after the end of the war, all government functions were to automatically “snap back” to their pre-war structure.

On May 24, 1945, Truman submitted a special message to Congress on government reorganization. In addition to discussing specific aspects of wartime reorganization that needed to be made permanent via legislation, Truman also urged Congress to give him broader reorganization authority:

…the following features are suggested: (a) the legislation should be generally similar to the Reorganization Act of 1939 and part 2 of Title I of that Act should be utilized intact, (b) the legislation should be of permanent duration, (c) no agency of the Executive Branch should be exempted from the scope of the legislation, and (d) the legislation should be sufficiently broad and flexible to permit any form of organizational adjustment, large or small, for which the need should arise.[1]

Seven months later, Congress gave Truman the Reorganization Act of 1945 (59 Stat. 613), but it did not meet all of Truman’s prerequisites. While the new power did have the same two-chamber legislative veto requirement as the 1939 Act (this was what Truman was referring to when he discussed “part 2 of Title I” of the 1939 law), the reorganization authority was not permanent – it would expire April 1, 1948. And section 5 of the new law limited its scope – Truman could not abolish or create Cabinet-level departments. He could not take anything away from the Interstate Commerce Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, or a few other independent commissions and boards.

No reorganization plan could impose, “in connection with the exercise of any quasi-judicial or quasi-legislative function possessed by an independent agency, any greater limitation upon the exercise of independent judgment and discretion, to the full extent authorized by law, in the carrying out of such function, than existed with respect to the exercise of such function by the agency in which it was vested prior to the taking effect of such reorganization.”

And section 5(c) of the law said “No reorganization plan shall provide for any reorganization affecting any civil function of the Corps of Engineers of the United States Army, or of its head, or affecting such Corps or its head with respect to any civil function. No reorganization contained in any reorganization plan shall take effect if the reorganization plan is in violation of this subsection.”

Truman signed the bill into law on December 20, 1945. He now had reorganization power, but he was powerless to move the railroad, motor carrier and inland waterway economic and safety regulation functions of the ICC or the river and harbor navigation and infrastructure functions of the Corps of Engineers.

Ernie Williams’ plan.

After Ernie Williams finished work on the “Transportation and National Policy” study of the National Resources Planning Board in 1942, which had recommended the creation of either a national transportation coordinator or else a U.S. Department of Transportation, he went to work for the War Production Board, and later became the head of the transportation division of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. (There’s no way to get better perspective on how to build your own national transportation system than by figuring out the best ways to destroy the well-organized national transportation systems of Germany and Japan by blowing them up.)

After Ernie Williams finished work on the “Transportation and National Policy” study of the National Resources Planning Board in 1942, which had recommended the creation of either a national transportation coordinator or else a U.S. Department of Transportation, he went to work for the War Production Board, and later became the head of the transportation division of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. (There’s no way to get better perspective on how to build your own national transportation system than by figuring out the best ways to destroy the well-organized national transportation systems of Germany and Japan by blowing them up.)

At war’s end, he took a job as a transportation analyst with the Bureau of the Budget (BoB). On December 28, 1945 (just eight days after the Reorganization Act became law), L.W. Hoelscher, head of the BoB Management Improvement Branch (and a protégé of the Brownlow Committee’s Luther Gulick, from the University of Chicago), sent around a circular memo asking all areas of the Bureau to think of ways for President Truman to use his new reorganization authority to make government more efficient.

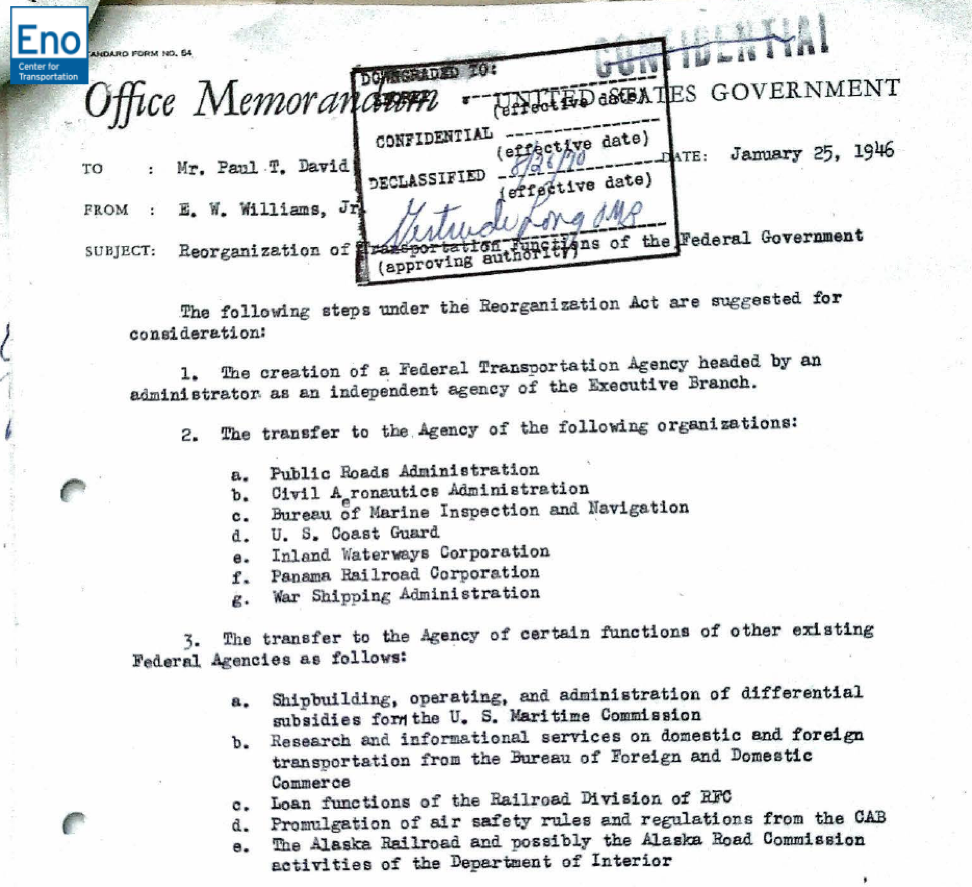

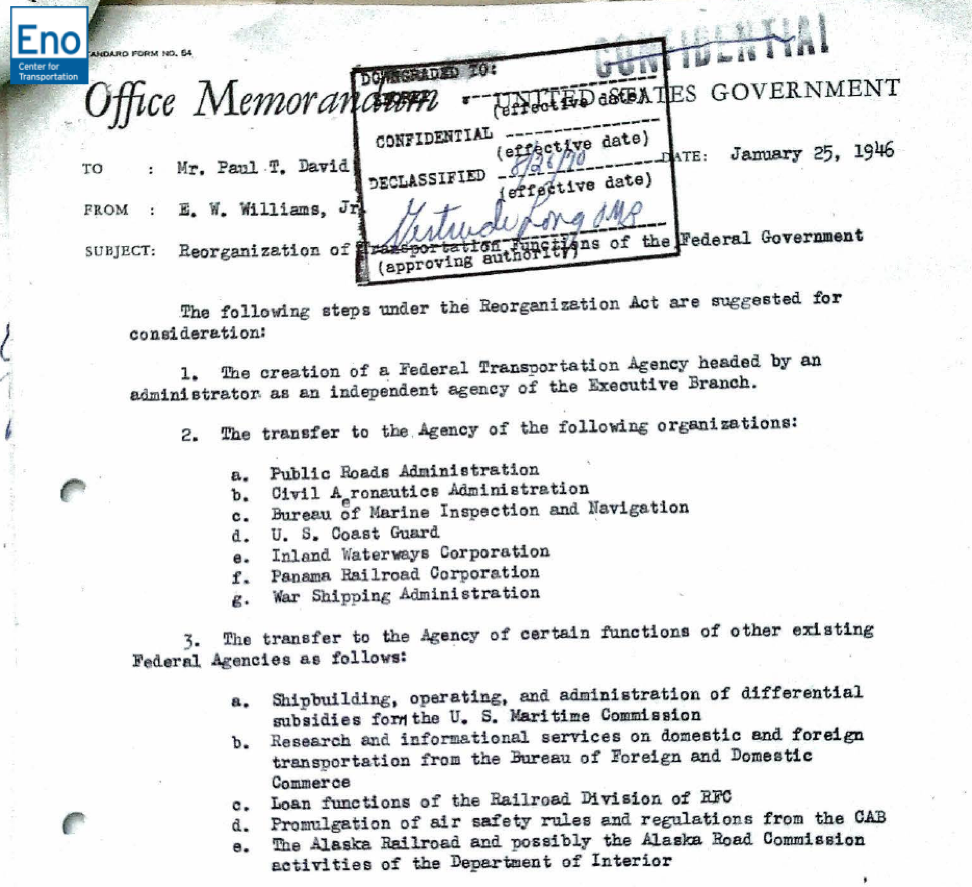

Ernie Williams responded on January 25, 1946, with an 8-page memo to his immediate boss, Paul T. David[2] advocating that President Truman create a Federal Transportation Agency that would have been a Department of Transportation in all but name:

Williams had to work within the strictures of the reorganization law – he couldn’t call it a “Department” or call its head a “Secretary,” and he couldn’t touch the ICC or the Corps of Engineers, but aside from those restrictions, his recommendation was comprehensive. His memo also discussed general concepts and definitions of transportation policy that are still relevant over 70 years later:

The activities of the Federal Government in transportation now fall roughly into five broad categories, viz.: economic regulation, safety regulation, business aids and promotion, operation of transport services, and provision of fixed facilities such as highways and port facilities. The three latter classes of activity differ fundamentally from economic regulation and cannot be successfully administered side by side in the same agency. Carrying out any large promotional program, whether a public works construction program, a subsidy program (with the exception of air mail payments closely tied to regulatory policy) or the actual operation of service tends to impart the agency concerned a commercial viewpoint often, not far different from that of the private commercial interests in the same field. Such commercial considerations tend to overwhelm any effort to regulate or to engage in deep detached research into the developing economics of the segment of the industry concerned. The combination of regulatory and promotional activities in a single agency is bound to fail, for the promotional takes precedence. The agency cannot successfully regulate its own operating and promotional activities in line with broad standards of the public interest and fails likewise to give proper attention to the regulation of related private operations under its jurisdiction. No agency should be called upon to attempt two functions so fundamentally opposite in character. The functions should be separated…

Safety regulation is something of a hybrid. The investigation of accidents and the preparation of recommendations to avoid similar recurrences in the future seems clearly best placed in a regulatory agency. On the other hand, the routine administration involved in enforcing safety regulations and inspecting facilities and equipment is more properly placed in an investigative body. The place for the promulgation of safety rules and regulations is not so easily determined, but on balance would seem to rest with the administrative agency leaving the regulatory body entirely free from any of the acts which might contribute to accidents coming under its review. A partial division of the safety functions has already been secured between the CAB and CAA in respect of air transport.[3]

Looking beyond the authority contained in the Reorganization Act, Williams also recommended the eventual consolidation, via legislation, of the economic regulatory authority of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Civil Aeronautics Board, and the Maritime Commission into a single regulatory Transportation Commission. He also recommended the eventual conversion of the Federal Transportation Agency into a full-fledged Department of Transportation, which would also include the rivers and harbors program of the Corps of Engineers, the safety and inspection functions of the ICC (except for accident investigations), and the emergency and service powers of the ICC (except for those relating to discrimination and adequacy in the public interest).

Williams also specifically rejected the idea, pushed by Presidents from Harding through Roosevelt, that all federal public works programs should be consolidated in one organization:

The combination in a transportation agency of the Bureau of Public Roads and other organizations having large public works responsibility would conflict with an organization designed to bring together all Federal activity in public works. The development of an adequate and well balanced transportation system, and one whose parts are properly coordinated, requires, however, the unification of Federal-aid and direct public works activities in transportation and their close juxtaposition to the general transportation and research policy making which would be set up effectively for the first time in the proposed transportation agency. This is of a public importance so great as to compel the merger of public works activity in transportation with the agency to be given primary responsibility in this area. As a part of general administration policy, one of the guiding considerations in the timing of the work would be the general [economic and employment] stabilization policy. The transportation agency would itself develop advanced planning with a view to securing a “shelf” of projects ready for construction as the needs of stabilization policy might indicate. A proper coordination with other public works planning and policy would be an obvious necessity.

The Budget Bureau adopts Williams’ plan.

Williams’ immediate superior, Paul David, concurred with the memo five days later and sent it upstairs to his superior, J. Weldon Jones (Assistant Director in charge of the Fiscal Division), along with an additional recommendation to add the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey and the Weather Bureau to the proposed transportation agency because of their close work in preparing maps and weather forecasts for aviation and marine navigation. David also recommended that “In view of its subject matter, the [Williams] memorandum should be treated as strictly confidential and its circulation within the Bureau should probably be controlled.”[4]

Naturally, news of the proposal leaked the very next day. A trade newspaper called American Aviation reported on February 1, 1946 that “A sweeping move to consolidate all transportation agencies of the government into a Department of Transportation is under consideration in the Bureau of the Budget, according to Congressional sources.”[5]

Williams’ views were not shared by all within the Bureau. One analyst opposed inclusion of the Coast Guard in a Transportation Agency because he did “not see any direct relationship of their activities to the transportation program” and also did not share Williams’ believe that economic regulation should be separated from other government transportation functions.[6] Another believed that the ICC “should be charged with responsibility for carrying out the National Transportation Policy. It should be given control over all carriers and it should be required to make studies and reports concerning aides [sic] and taxation to assist in carrying out the policy.” But he added the caveat that “It would be entirely proper, and probably advantageous, to have the running of airports, inspection of locomotives, and some of the some of the public roads functions performed by an operating agency.”[7]

On March 7, 1946, President Truman met with his Budget Director, Harold Smith, to discuss possible plans under the Reorganization Act. Truman “expressed great interest in possible action the transportation field,” so Smith promised him a memo on the subject.[8] Director Smith was presented with a draft memo for President Truman on April 2 that would have asked Truman to choose between three plans: (1) the full Williams proposal, (2) the full Williams proposal plus moving all CAB aviation and Maritime Commission regulation into the new agency as well, or (3) leaving roads and aviation out of it and just doing a Federal Maritime Agency. The cover memo to Director Smith also asked him to decide a few other questions, such as whether or not the Director should just make one recommendation to Truman and whether or not the memo should suggest future consolidation via legislation that would touch the ICC and the Corps.[9]

By April 11, Williams was assembling a list of possible Federal Transportation Agency heads that included Paul Nitze (with whom Williams had served on the Strategic Bombing Survey), former Budget Director Lewis Douglas, CAB chairman L. Welch Pogue, and former ICC chairman Charles Mahaffie.[10]

Refining the plan.

Around this time a decision was apparently made to pursue two tracks at once – Bureau staff composed a draft plan for creation of a Federal Transportation Agency (to include aviation, roads, inland waterways, and Coast Guard and the various maritime agencies), but they also prepared a draft plan creating a Federal Maritime Agency (the various maritime agencies plus the Coast Guard). Being contradictory, the President could not choose both. (The two plans did have one thing in common – both would have transferred the ship registry, enrollment, and licensing functions of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation to the Customs Bureau.)

Both plans would also have created a Maritime Board (either within the Transportation Agency or else within the Maritime Agency) to retain the quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative functions of the Maritime Commission plus operating the ready reserve and the Merchant Marine Academy.

On April 17, BoB staffer Ralph Burton prepared a memo with the subject line “Issues re Transportation Reorganization Plan.” After a page of questions with respect to a possible Maritime Agency (most of which revolved around what powers would go to the Agency head and which would go to the Board), it then listed the following questions to be answered:

II. With Respect to a Transportation Agency.

The issues listed above plus:

- Shall we preserve the identity of [the Public Roads Administration], [the Civil Aeronautics Authority], and Coast Guard?

- Shall we provide for an Assistant Administrator?

- Shall we transfer research and statistical functions to the Administrator?

- Shall we vest in the Administrator the function of adopting rules and regulations under the laws administered by the Agency or its constituents?

- Shall the appointment of heads of constituents be vested in the Administrator rather than in the President with Senate approval?[11]

By April 26, Donald Stone, BoB Assistant Director for Administrative Management, had prepared a comprehensive memo for Director Smith on the subject. It recommended a reorganization plan creating a Federal Transportation Agency to include Public Roads, CAA, CAB, Maritime Commission, War Shipping Agency, the Coast Guard, the Inland Waterways Corporation, the Weather Bureau, and the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation. The draft plan had two alternatives for the distribution of maritime functions between an Administrator and a Board (Alternatives A and B for section 6 of the plan).

The memo also had an appendix with additional proposals for consideration – the Williams proposal to keep the CAB and Maritime Commission outside of the new agency for potential combination with the ICC via legislation, a possible recommendation to Congress that the Agency be converted via legislation to a Department of Transportation (with a corresponding change in the name of the Department of Commerce to the Department of Trade and Industry), and possible changes to remove the Weather Bureau and/or the Coast Guard from the Transportation Agency.[12]

The final draft of the Federal Transportation Agency reorganization plan was dated May 8, 1946. The plan would have transferred all of the agencies to the FTA that the law allowed – CAA, CAB, Public Roads, Coast Guard, Maritime Commission, War Shipping Administration, inspection services of the BMIS, Inland Waterways Corporation, the Customs functions relating to undocumented vessels, and the Weather Bureau. Non-economic regulatory authority, the conduct of research and statistical activities, and submission to Congress of annual reports was to be vested in the FTA Administrator, not the component heads. The CAA, Public Roads, the Coast Guard and the Weather Bureau were to retain their identities within the new Agency (with their own Directors (or Commandant in the case of the Coast Guard), along with “Such constituent unit or units as the Federal Transportation Administrator shall establish to administer the functions of the Agency relating to water transportation.”[13]

With regards to economic regulation, the CAB was to be renamed the Civil Aeronautics Commission was to retain its independence within the FTA, just as it had within the Commerce Department as moved by the reorganization plan in 1939.

But in the May 8 draft, section 6(a), defining the functions of the Maritime Commission, was left blank, indicating that decisions had not been reached about the division of labor between the Commission and the FTA itself.

The problems proved insurmountable for the time being. On May 16, 1946, President Truman submitted three proposed reorganization plans to Congress, and neither the Federal Transportation Agency plan nor the Federal Maritime Agency plan was among them. The only transportation-related element to survive was the breakup of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation – section 7 of the May draft of the FTA plan (giving BMIS ship registration and licensing to the Treasury Department) became section 102 of Plan No. 3, and section 1(9) of the May draft of the FTA plan (which had moved the rest of the BMIS to the FTA) was repurposed into section 101 of Plan No. 3 except that those functions were moved to the Coast Guard instead of to a Federal Transportation Agency.[14]

Congress allowed Plan No. 3 to take effect on July 16, 1946. No further reorganization plans were submitted to Congress in 1946.

Why didn’t the President submit either the FTA or Maritime plans to Congress? Nothing in the Bureau of the Budget subject file provides a full explanation, except for a line in a memo six months later stating “Due to time pressures and strategic considerations, no transportation plan was subsequently proposed although the Bureau put in considerable work on such a plan.”[15] But since the maritime section was left blank in the May 8 draft, the best guess is that maritime issues were primarily to blame.

The budget separates transportation from public works.

While Williams and the rest of the BoB team were not successful in convincing President Truman to propose the creation of a Federal Transportation Agency in 1946, Williams’ ideas about grouping transportation-related public works programs separately from other public works programs, and about drawing a distinction between the regulation of a thing and the provision or promotion of the thing, were implemented in a far-reaching way that was also decided that year.

On January 3, 1947, President Truman submitted his fiscal year 1948 budget request to Congress. The 1948 budget made fundamental changes in the way federal spending was organized and presented for analysis. Under the Roosevelt Administration, and in Truman’s first budget the year before, all federal spending was divided amongst 11 functional categories, and every individual appropriation was split up between categories for analysis each year. “General Public Works Program” was one of those categories, which matched Roosevelt’s decision to put as many public works agencies as possible together in the Federal Works Administration.

The 1948 budget was fundamentally different. It used the appropriations account as a fundamental and indivisible unit of measurement and assigned each account to a single function of government based on the account’s primary characteristics. And it went from 11 to 14 functions, while breaking up the “public works” category. The explanation starting on p. 1343 of the budget states that “’Public works’ no longer appears as a separate category in the functional classification. Instead, public works are distributed among the functions which they serve.”[16]

Federal Budget Functional Categories

|

| FY 1947 Budget |

FY 1948 Budget |

| National Defense |

050 Defense |

| Interest on the Public Debt |

100 Veterans Services and Benefits |

| Refunds |

150 International Affairs and Finance |

| Veterans Pensions and Benefits |

200 Social Welfare, Health, and Security |

| International Finance |

250 Housing and Community Facilities |

| Aids to Agriculture |

300 Education and General Research |

| Social Security, Relief and Retirement |

350 Agriculture and Agricultural Resources |

| General Public Works Program |

400 Natural Resources (non-Agricultural) |

| General Government |

450 Transportation and Communication |

| Anticipated Supplemental Appropriations |

500 Finance, Commerce, and Industry |

| Public Debt Retirement |

550 Labor |

|

600 General Government |

|

650 Interest on the Public Debt |

|

700 Refunds of Receipts |

The 1948 budget also reintroduced the concept of budget subfunctions. (The Harding Administration starting in FY 1924 used subfunctions but the Roosevelt Administration ended it in FY 1936.) This meant that every appropriations account would be assigned to a subfunction and then the subfunctions would be totaled into a function. The Transportation and Communications function in the 1948 Budget included no less than six transportation subfunctions which reflected Williams’ distinction between promotion, provision, and regulation of types of transportation:

| Transportation Subfunctions in the FY 1948 Budget |

| 451 |

Promotion of the merchant marine |

| 452 |

Provision of navigation aids and facilities |

| 453 |

Provision of highways |

| 454 |

Promotion of aviation, including provision of airways and airports |

| 455 |

Regulation of transportation |

| 456 |

Other services to transportation |

The system of using the appropriations account as a (mostly) indivisible unit and assigning each account to a subfunction and thence to a function is still in use today.

Congress changes hands and demands a say in reorganization.

On November 5, 1946, Democrats lost control of the House and Senate in the midterm elections, losing 12 Senate seats and 55 seats in the House of Representatives. The upcoming 80th Congress would take a much more skeptical eye towards all Truman Administration proposals.

The elections did not stop Bureau of the Budget staff from preparing to submit more reorganization plans to the upcoming Congress. Ralph Burton drafted a memo on November 21 for his superior Donald Stone to send to the Budget Director that re-emphasized the need for transportation organization and suggested two possible alternatives: “(1) establishment of a Transportation Agency; (2) transfer of various agencies and functions to the Department of Commerce. Under either alternative, various alternative dispositions of the functions of the Maritime Commission must be considered.”[17]

By January 10, 1947, Ernie Williams had prepared an outline for a potential presidential message to Congress on transportation reorganization that would point out all of the flaws of the existing division of responsibilities but would propose actual legislation (not a reorganization plan) to create a Department of Transportation and, separately, the transfer of the aviation and maritime economic regulatory powers of the CAB and Maritime Commission, respectively, to the ICC.[18]

This was all turned into a draft memo to President Truman by March 28 that led off by repeating a quote that Truman himself had uttered as a Senator in 1939:

We all know that if two bureaus are in the same Executive department, one sometimes, through the head of the Department, can get them to cooperate, and if they are in different Executive departments and under different Executive heads, even the President himself sometimes cannot get them to cooperate. If we are going to have a transportation system and a transportation policy for the country, the regulations must be centered in one head in which the country has confidence.[19]

The draft memo also indicated that since the Reorganization Act prevented the ICC from being included in a new Transportation Agency, “it would not be a true transportation agency…All major forms of transport would not be included. In the absence of apparent concern on this matter the wisdom of proceeding at all unless the entire field can be handled is open to question.”[20] It then asked if the President would consider sending Congress a message asking for transportation reorganization legislation that did include the ICC.

But nothing came of the proposal. It soon became clear that the 80th Congress wanted more input into government reorganization proposals before they were submitted to Congress for an up-down vote. On January 10, 1947, Congressman Clarence J. Brown (R-OH)[21] introduced a bill in the House of Representatives (H.R. 775, 80th Congress) creating a blue-ribbon panel to study executive branch reorganization and recommend reorganization plans and legislation to the President and Congress. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. (R-MA) introduced a very similar bill in the Senate (S. 164, 80th Congress) the following day.

Those bills were reported from committee unanimously in the Senate and House on June 24 and 25, respectively. The House took up H.R. 775 by unanimous consent on June 26. During the debate, the only member who made remarks was Minority Whip John McCormack (D-MA), who spoke enthusiastically in favor of the bill and of Brown’s leadership on the topic.[22] The House passed the bill by unanimous consent and then the Senate passed the House bill without amendment by unanimous consent the following day.

President Truman signed the bill into law on July 7, 1947 (61 Stat. 246). It created a Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, to report its findings and recommendations by January 1949. The Commission would have the following members:

Sec. 3. (a) Number and appointment.-The Commission shall be composed of twelve members as follows:

(1) Four appointed by the President of the United States, two from the executive branch of the Government and two from private life;

(2) Four appointed by the President pro tempore of the Senate, two from the Senate and two from private life; and

(3) Four appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, two from the House of Representatives and two from private life.

(b) Political affiliation.-Of each class of two members mentioned in subsection (a), not more than one member shall be from each of the two major political parties.

By July 17, all twelve members of the Commission had been appointed:

| Appointment by |

From Government |

From Private Life |

| President (D) |

James Forrestal |

Dean Acheson |

| President (R) |

Arthur Flemming |

George H. Mead |

| House (D) |

Carter Manasco (AL) |

James Rowe, Jr. |

| House (R) |

Clarence Brown (OH) |

Herbert Hoover |

| Senate (D) |

John L. McClellan (AR) |

Joseph P. Kennedy |

| Senate (R) |

George Aiken (VT) |

James K. Pollock |

House Speaker Joe Martin (R-MA) appointed former President Herbert Hoover to the Commission – but Hoover only agreed to serve on the condition that he be named its chairman, to which President Truman agreed.[23] Even though Truman’s authority to propose reorganization plans would not expire until April 1948, all major government reorganization proposals – including those to create a Department of Transportation – would now have to wait for the “Hoover Commission” to finish its work.

Part 3 of this series can be read here.

[1] Truman, Harry S. “Special Message to the Congress on the Organization of the Executive Branch.” Public Papers of the Presidents – Harry S. Truman: 1945 : Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, April 12 to December 31, 1945. Washington: Government Printing Office 1961 pp. 69-72.

[2] Paul David was, at the time, the head aviation policy expert at BoB. See his fascinating account of the 1944 Chicago Conference in David, Paul T. “A Review of the Work at the Chicago Conference on International Aviation (From a Secretariat Point of View). Printed as Chapter 12 of Thompson, Kenneth W. (Ed.), Diplomacy, Administration and Policy: The Ideas and Careers of Frederick E. Nolting, Jr., Frederick C. Mosher, and Paul T. David. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1995.

[3] E.W. Williams Jr. memo to Paul T. David dated January 25, 1946 with subject line “Reorganization of Transportation Functions of the Federal Government.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[4] Paul T. David memo to J. Weldon Jones dated January 30, 1946 with the subject line “Attached Memorandum on Reorganization of Transportation Functions.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[5] Dobben, Gerard B. “May Consolidate Transportation Agencies – Budget Bureau Considering Move Which Would Place CAB, CAA Under Single Transportation Department.” American Aviation, February 1, 1946, p. 13.

[6] C.H. Schwartz, Jr. memo to Arnold Miles dated February 11, 1946 with the subject line “Proposal to consolidate CAA, CAB and USMC into a Federal Transportation Agency.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[7] W.K. Hall memo to C.H. Schwartz, Jr. dated February 6, 1946 with the subject line “ODT Reply to Budget Bureau Bulletin 1945-46:15.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[8] The source is a draft memo for Budget Director Smith to send to President Truman. The draft memo is undated but has a cover memo dated April 2, 1946 from D.C. Stone to the Director. Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ernest W. Williams, Jr. memo to Paul T. David dated April 11, 1946 with the subject line “Possibilities for the Head of the Proposed Transportation Agency.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[11] R.E. Burton draft memo dated April 17, 1946 entitled “ISSUES RE TRANSPORTATION REORGANIZATION PLAN.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[12] Donald C. Stone memo to Budget Director Smith dated April 26, 1946 with the subject line “Transportation Plan.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[13] Draft reorganization plan entitled “Reorganization Plan No. ___ of 1946” dated May 8, 1946 to create a Federal Transportation Agency. Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[14] The reorganization plans were printed in Congressional Record (bound edition), May 16, 1946 on pp. 5149-5156.

[15] Draft memo to be sent from Donald C. Stone to Budget Director Smith, written by Ralph Burton and dated November 21, 1946 with the subject line “Reorganization Action in the Transportation Field.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[16] U.S. Bureau of the Budget. The Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1948. Washington: Government Printing Office 1947 p. 1343.

[17] Stone to Smith memo dated November 21, 1946 cited above.

[18] Ernest W. Williams Jr. memo to D.B. Stauffacher dated January 10, 1947 with the subject line “Outline of Presidential Message on the Reorganization of Federal Transportation Agencies.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[19] D.B. Stauffacher draft memo to President Truman dated March 28, 1947 with the subject line “Establishment of a Transportation Agency.” Located in the transportation reorganization subject files of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Congressman Brown was the grandfather of the actor Clancy Brown, who played the villainous immortal Kurgan in the awesome 1986 movie Highlander. There can be only one.

[22] Congressional Record (bound edition), June 26, 1947 pp. 7755-7757.

[23] The Hoover and Truman Presidential Libraries have published online a joint project called “Hoover & Truman: A Presidential Friendship.” The source for this statement is taken from item 78 in “Part IV – Reorganizing the Executive Branch” retrieved on April 8, 2019 at https://www.trumanlibrary.org/hoover/ebranch.htm

After Ernie Williams finished work on the

After Ernie Williams finished work on the