May 5, 2017

Enthusiasm for automated vehicle (AV) technology has ballooned in recent years as automakers and tech firms move ever closer to deploying fully self-driving cars. The potential of this nascent technology has captured the imagination of the public and policymakers alike with its promise of reducing traffic fatalities, increasing efficiency, and encouraging the use of shared vehicles.

The safety benefits in particular are well known and oft cited: 40,000 lives were lost on America’s roadways last year, with 1.2 million more people injured. Human error and human choice were the cause for 94 percent of accidents, due to factors such as recklessness, inebriation, and distraction. This is not only a preventable loss of loved ones, friends, and colleagues, but also a tremendous loss of human potential.

Much ink has already been spilled by industry observers and lawmakers speculating about how AVs will revolutionize personal, commercial, and public transportation. An automated system does not drive while inebriated, distracted, or angry – and will potentially be able to make better and faster decisions that will prevent accidents.

While AV technology was born out of nearly utopian speculation, it will require sound policies and conscious development in order to realize its full potential.

Amid all of the hype over the technology, nuance was sacrificed for enthusiastic expedience. Discussions around AVs have become disjointed, largely due to a lack of clarity about the technology’s precise capabilities and limitations in public discourse. Myriad terms with different meanings are used in legislatures and the media – self-driving, driverless, autonomous, and automated.

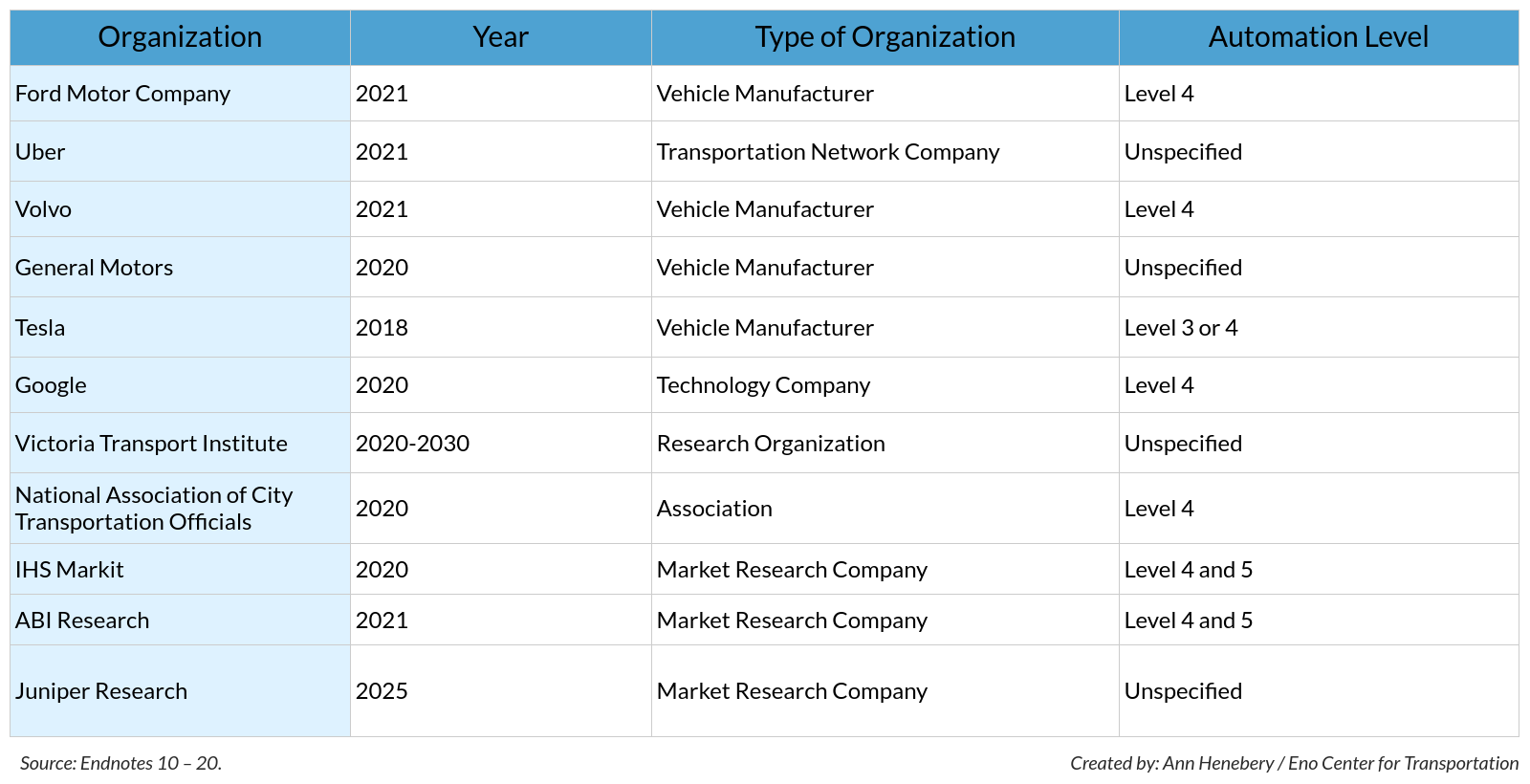

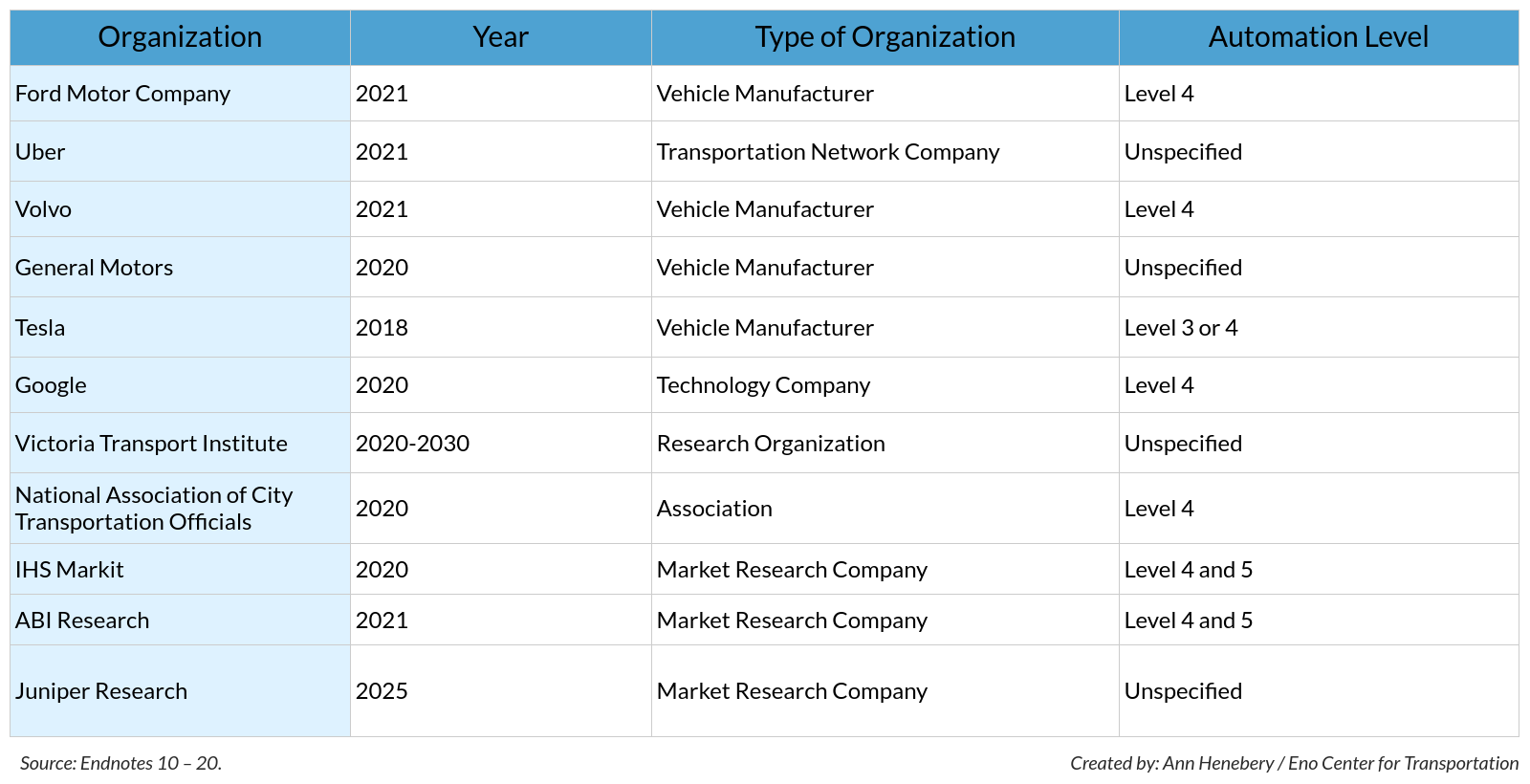

Automakers, tech firms, and other organizations boldly predict the imminent market deployment of AVs while referencing different degrees of automated driving capabilities, or none at all.

Expected Commercial Availability of Level 3 or Higher Vehicle Automation, by Select Organization

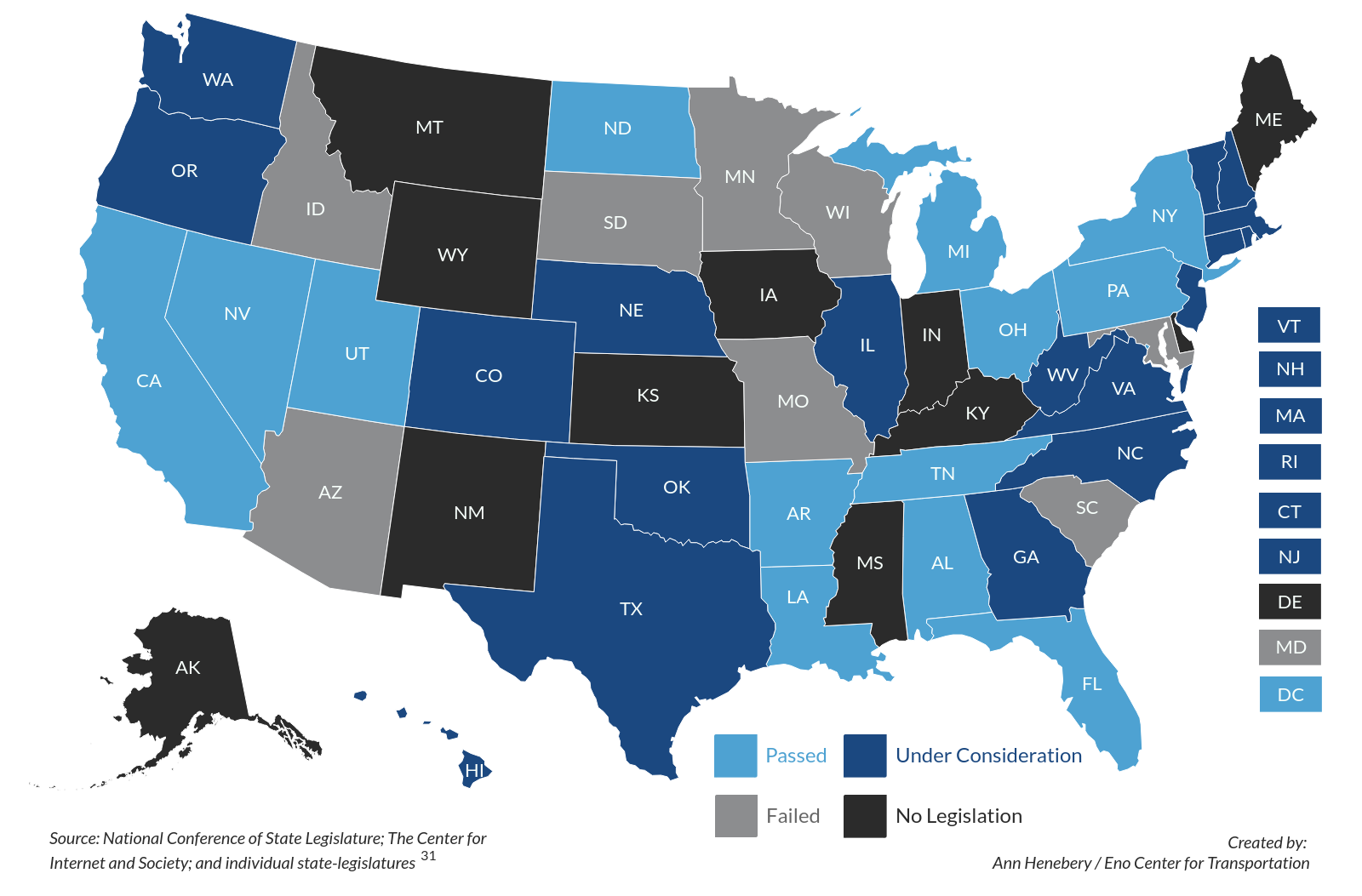

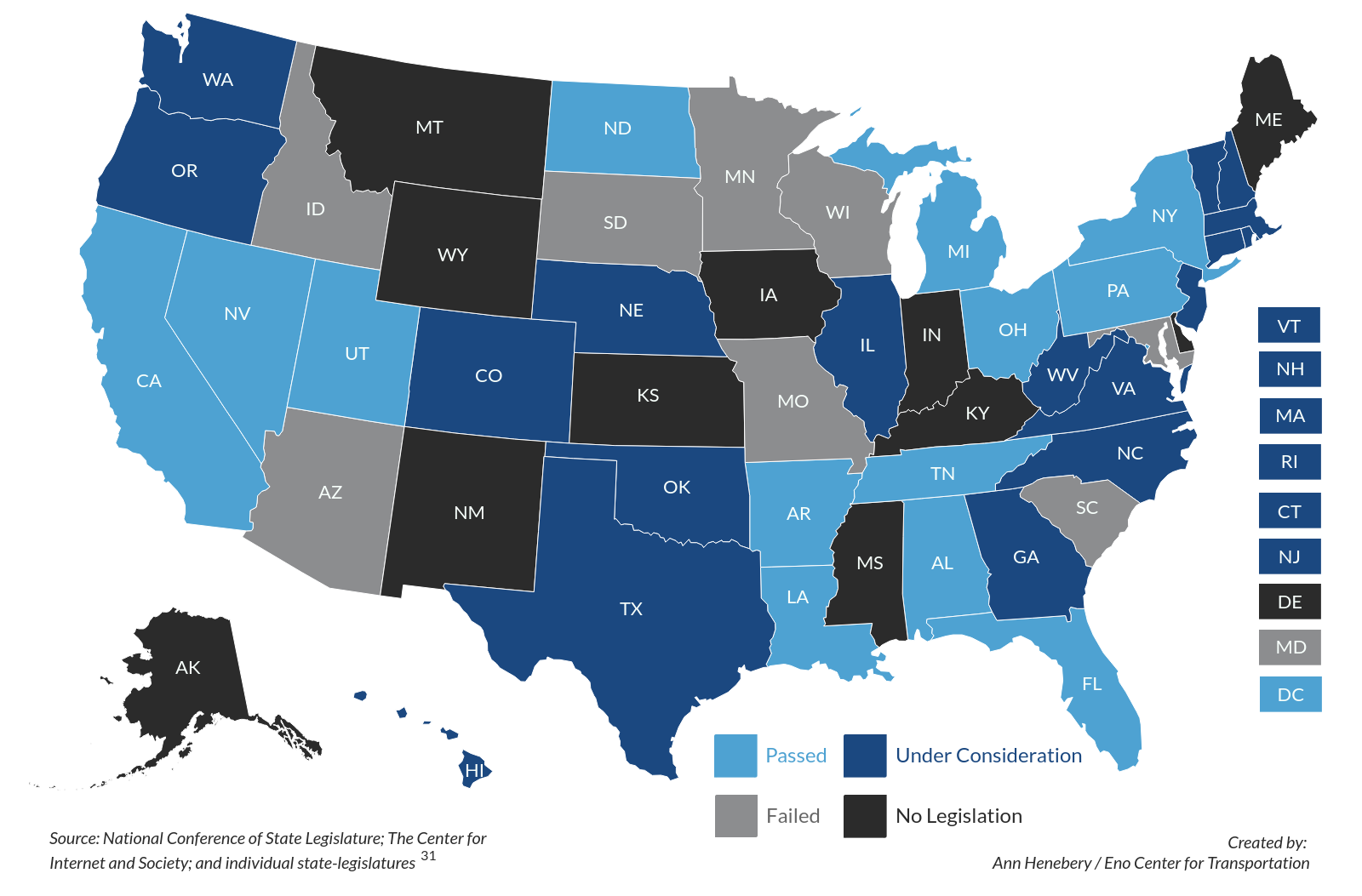

This has produced confusion over the capabilities and limitations of automated features in vehicles – an issue that has only been compounded as 39 states have considered or passed legislation across the past several years using disparate terms for, and regulations on, AVs. This has resulted in a patchwork of state regulations that ultimately complicate industry efforts to test AVs across the country. If this proceeds unchecked, automakers and tech firms could be deterred from national deployment due to the difficulties of grappling with up to 50 disparate regulations.

Status of State Legislation Related to Automated Driving, April 2017

For this reason, the Eno Center for Transportation undertook an extensive research initiative to understand the current state of AV development as well as the regulations affecting them at the federal, state and local levels. Using this research and collaborating with the Eno Digital Cities Working Group, Eno developed a set of 18 recommendations for sound policies that will guide AV development from the testing phase to market deployment without sacrificing safety or stymieing innovation.

The report, titled Beyond Speculation: Automated Vehicles and Public Policy, establishes a foundation for lawmakers and regulators to implement sound AV policies at the federal, state, and local levels of government.

The initial step is almost deceivingly simple, but forms the foundation for all 18 recommendations: in order to fulfill their respective roles in regulating AVs, policymakers need to first ascertain the state of the technology now and current development trajectory. This begins with understanding the definitions of vehicle automation, as adopted by the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) last September and defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE).

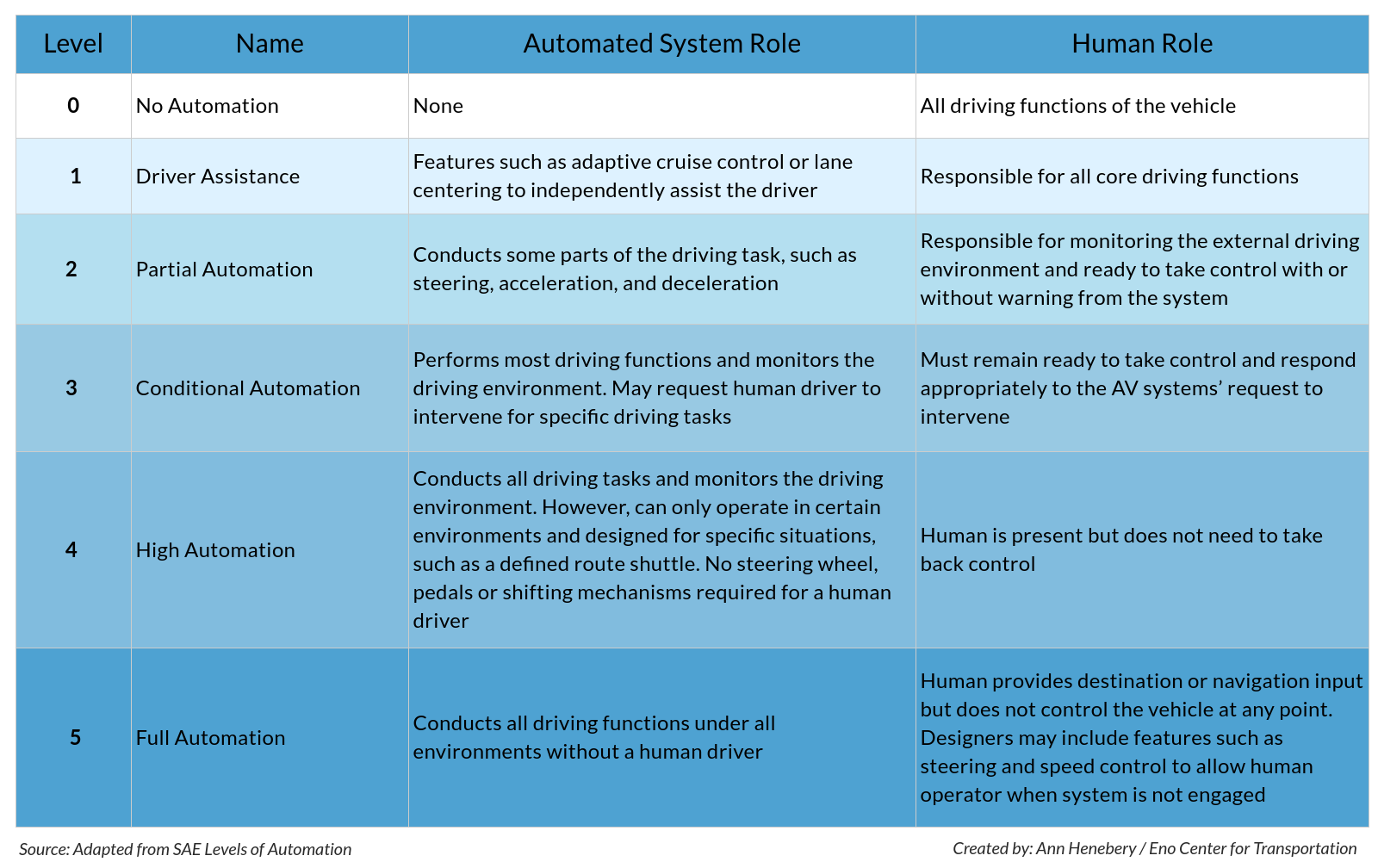

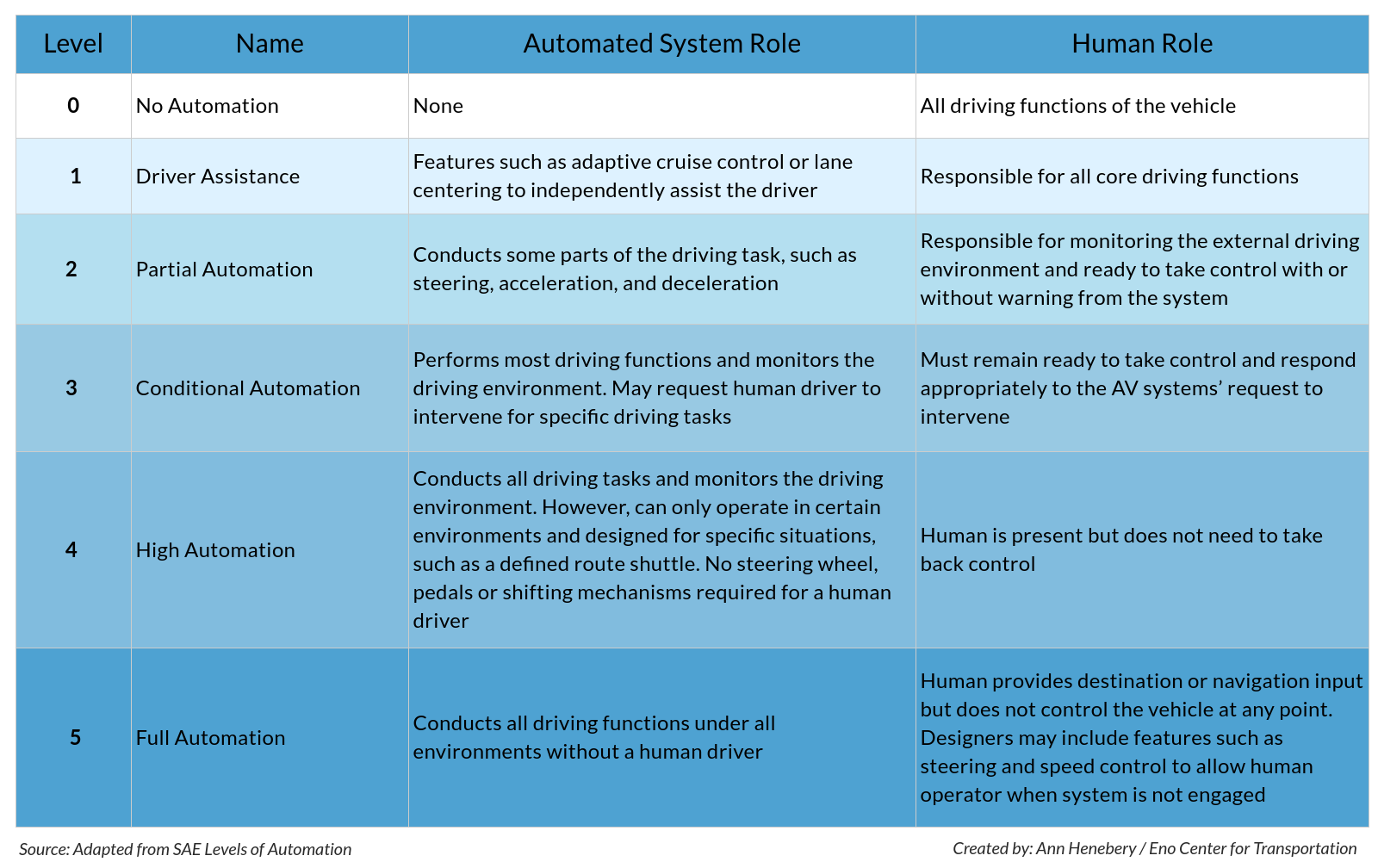

Vehicle automation is not a binary measure of on or off, but manifests as a gradient of automated features that are gradually being integrated into cars. Automated features are already present in most cars on the road today, and as more automated features are introduced, the division of responsibility for the driving task shifts from the automated system to the driver. In order to clarify the division – and diffusion – of responsibility, SAE defined 6 degrees of vehicle automation that range from level 0 (not automated) to level 5 (fully automated), as shown below.

Classification System for Vehicle Levels of Automation

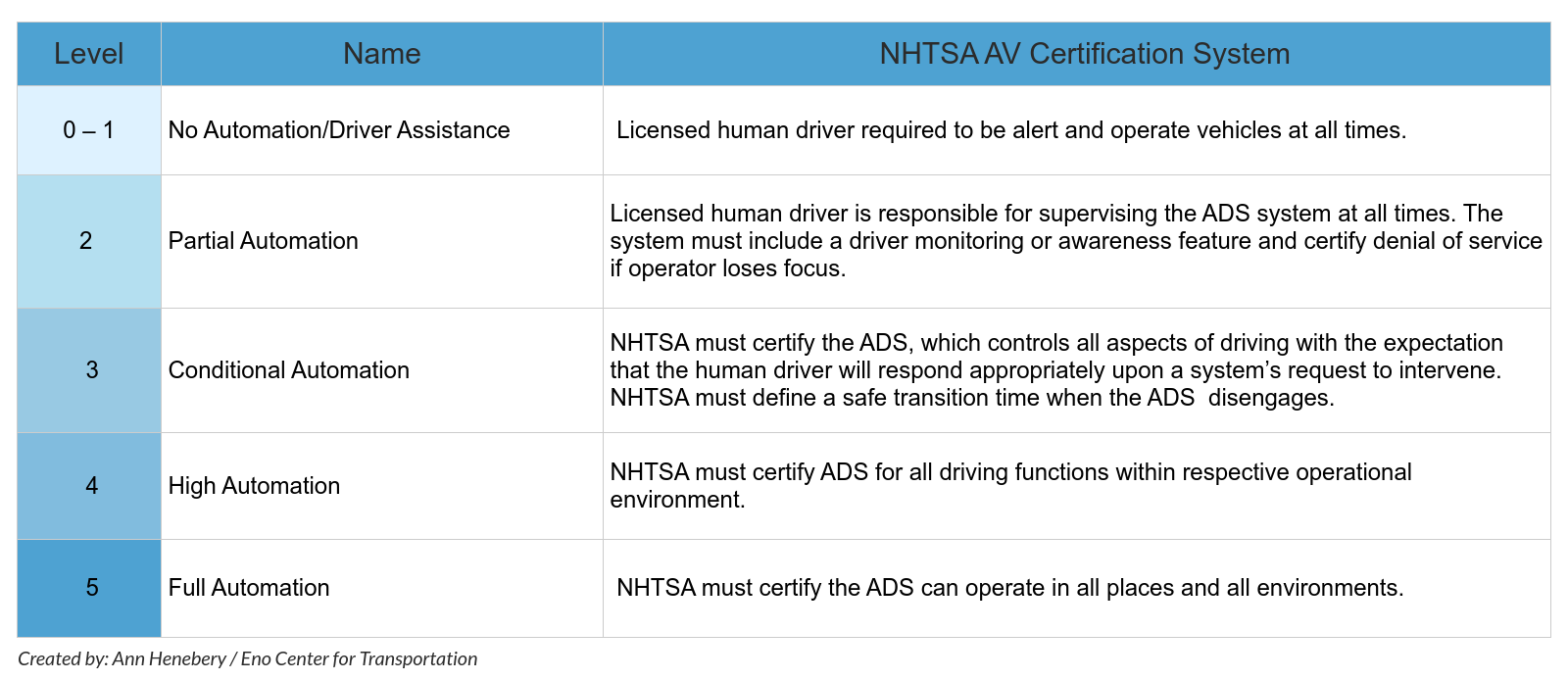

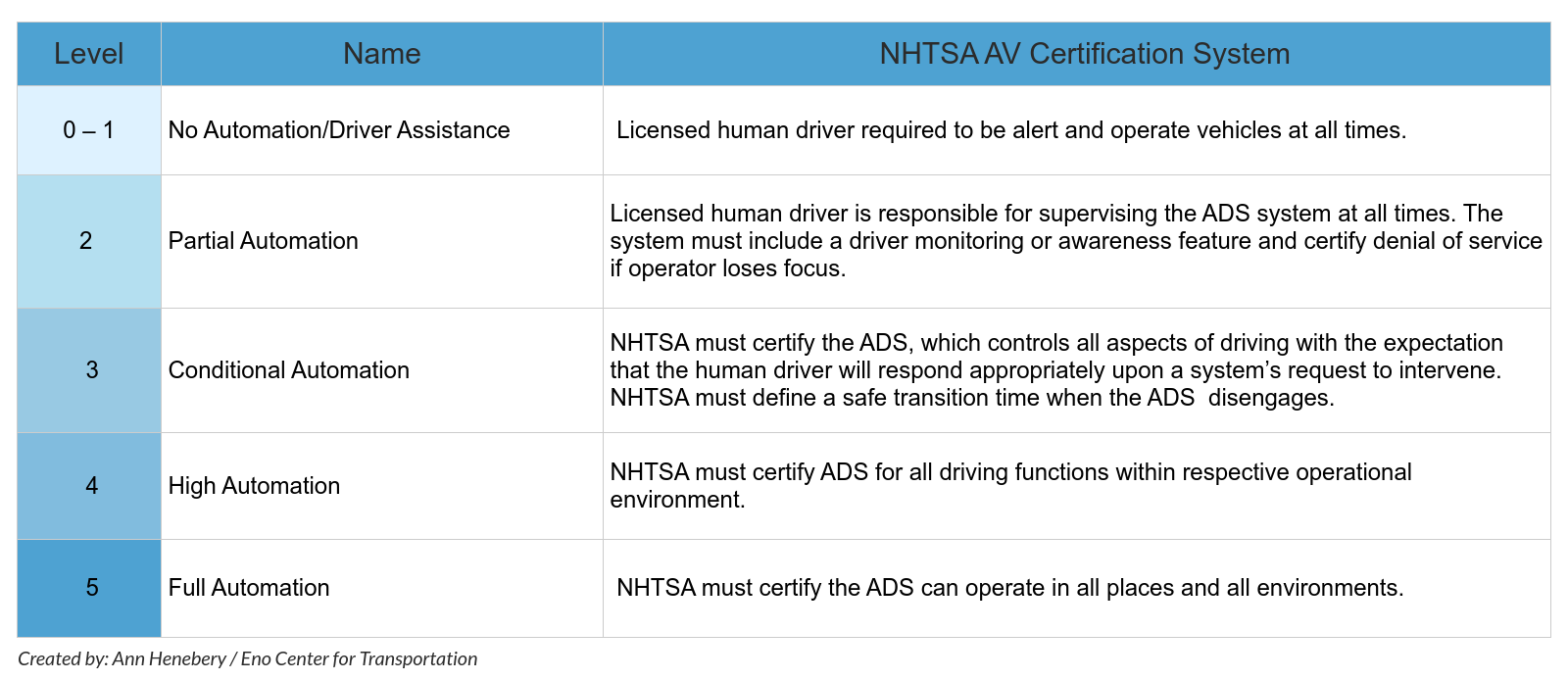

NHTSA has traditionally regulated the design and performance of the physical components of vehicles, not automated features that rely on a combination of physical components, sensors, and software. Due to the nature of automated systems, the prescriptive regulations that have been codified as Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) are not suitable for regulating AV performance as the technology develops.

For this reason, Eno recommends that Congress should authorize NHTSA to develop a new certification system based on automated vehicle capabilities and limitations from level 3 to level 5. This will allow policymakers and industry to accurately articulate each vehicle’s degree of automation, providing greater regulatory certainty while also informing consumers of how they should expect their vehicle to perform. Ultimately, establishing this common foundation for policymakers and the public will shift the conversation about automated vehicles from projection into a tangible reality.

Certification Levels for Automated Driving Systems (ADS)

Eno recommends that the federal government, not individual states, be responsible for approving AVs and AV technology. This will allow states to focus on their core responsibilities of licensing human drivers, insurance regulation, and vehicle registration and inspections.

This simultaneously empowers NHTSA in its role as the sole regulator of vehicle safety in the national market and opens the door for preemption of state laws enacting incongruent regulations on the design and performance of AVs.

Due to the massive amounts of data that will be generated by AVs (up to 100GB per second) federal government should also explicitly require the AV industry to protect the privacy of vehicle owners and the data generated from the systems.

Eno also found that AVs have the potential to disrupt the transportation workforce—especially imperiling the 4 million people employed as truck, bus, taxi, and delivery drivers. Therefore, policymakers need to move to implement retraining and career development programs to offset the negative aspects of automation even as it leads to the creation of new industries and occupations.

While the federal government has a central role to play in the national testing and deployment of AV technology, engagement from states and localities will be vital for the long-term implementation.

Furthermore, Eno recommends that states and localities consider the transformational power of AVs in developing their long-term plans and enter into data sharing agreements with AV developers that allow them to use the tremendously valuable information that will help them to achieve their goals of decreasing congestion, enhancing mobility, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The full report, Beyond Speculation: Automated Vehicles and Public Policy, is available on Eno’s website and provides eighteen specific recommendations aimed at the following issues: