Transactions in cash-based accounting are recorded when payments are actually made or receipts collected. By contrast, accrual measures summarize in a single number the anticipated net financial effects at a specific point in time of a commitment that will affect federal cash flows many years into the future. That is, accrual methods record the estimated value of expenses and related receipts when the legal obligation is first made rather than when subsequent cash transactions occur.

Most of the federal budget uses cash-based accounting and always has. The federal deficit or surplus is measured by comparing the cash coming in the door (tax receipts, user fees, etc.) with the cash going out the door (outlays). The big exception, since 1990, is federal credit programs, where the eventual net total cost to the federal government of the loan, over 30 years (or however long the loan life is), is booked at the time the loan is made. When the federal government makes a TIFIA loan, for example, that nine-figure check written to a state or locality is not recorded as a federal outlay – only the estimated lifetime net cost of the loan gets recorded as an outlay.

(Interestingly, the 1967 President’s Commission on Budget Concepts recommended in its final report that the federal government switch over from cash accounting to accrual accounting for expenditures. The recommendations of the Commission are generally regarded as holy writ by CBO and OMB, but Presidents Johnson and Nixon delayed the implementation of accrual accounting because the Pentagon said they needed more time, what with the Vietnam war and all, and the issue was later dropped.)

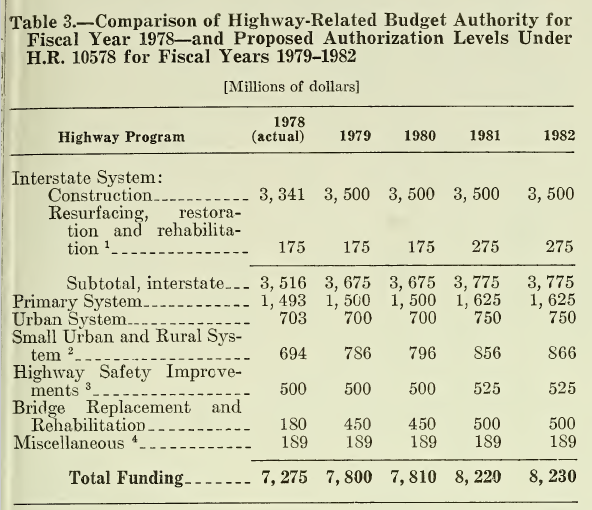

The difference between the two types of accounting systems gets clearer when you look at spending commitments that take a long time to “spend out.” Under cash-based accounting, if Congress increases highway spending by $1 billion in 2018, only about $250 million of that money shows up as an expenditure (outlay) from the Highway Trust Fund in that year. The rest of that $1 billion can take six or seven years to “spend out” fully. But if the Trust Fund operated under accrual accounting, the full $1 billion would be booked in the Trust Fund in 2018 and would be measured against future scheduled Trust Fund tax revenues.

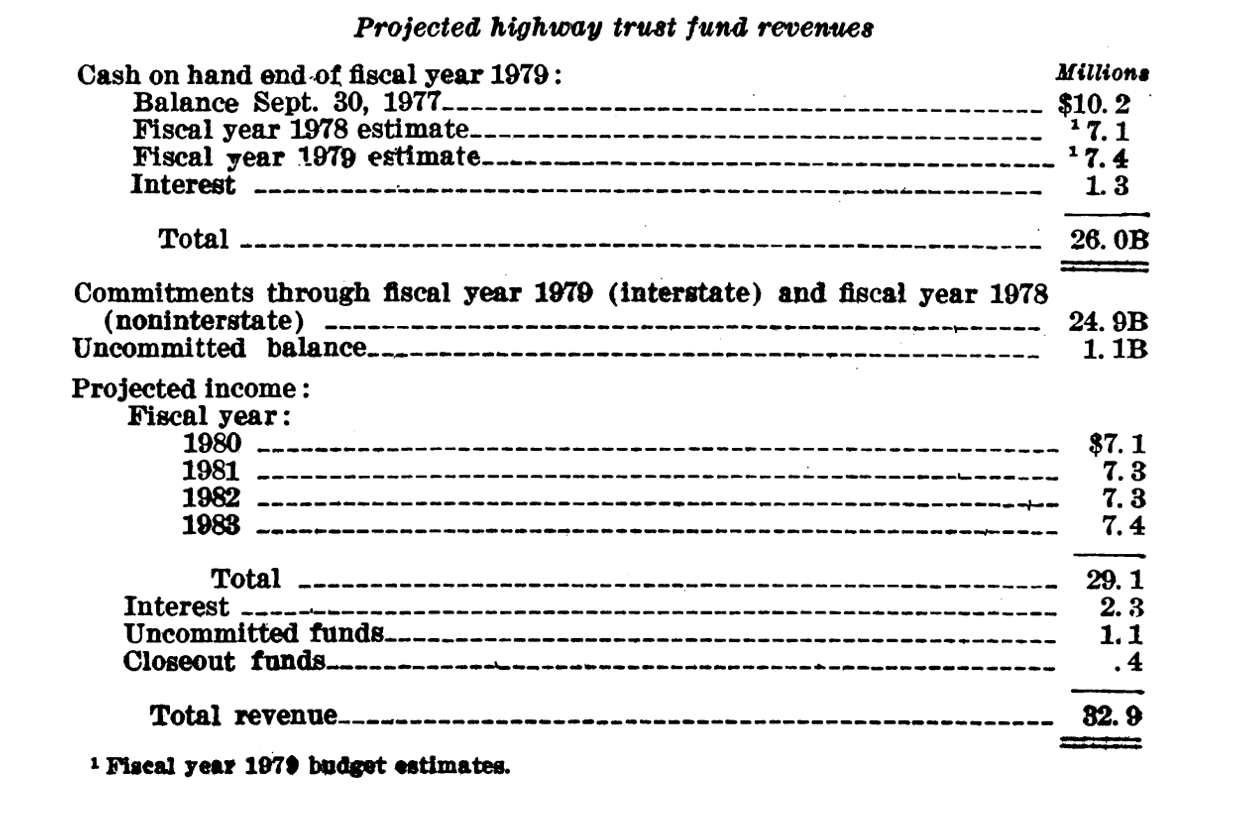

Cash versus accrual also makes a huge difference when conceptualizing the balance of a trust fund account. Cash based accounting looks at the cash balance of a trust fund at any given time. But accrual accounting looks at the unobligated, or uncommitted, balance. This is critically important – what looks like a huge cash balance can, in fact, be mostly or entirely obligated for specific programs and projects already and is simply awaiting outlay. Just because cash is sitting in a trust fund does not mean that the money is available to pay for new spending commitments.

Jimmy Carter and Brock Adams. The 1976 Presidential election sent Jimmy Carter to Washington, where his party would have control over a unified federal government for the first time in eight years. In the Congressional elections, Democrats won 292 seats in the House (just over two-thirds) and 61 seats in the Senate (enough to shut down filibusters). In terms of momentum and sheer numbers, the 95th Congress had the potential to be as game-changing as the Great Society Congress of 1965-1966.

For his Secretary of Transportation, Carter chose 12-year incumbent Congressman Brock Adams (D-WA). Adams had been a member of the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee and its Subcommittee on Transportation and Aeronautics, which had jurisdiction over railroads, the economic regulation of interstate trucking, and (until January 1975) over aviation as well. But also, from 1975-1977, Adams had been the first real chairman of the House Budget Committee. (Al Ullman (D-OR) had been chairman from August-December 1974 but the panel wasn’t really going then.) As such, Adams had been a key participant in the establishment of the new Congressional budget process and was one of the main advocates of giving the new Budget Committees an important role in forcing other Congressional committees to keep their spending within the bounds set by the budget resolution.

Adams took several Budget Committee staffers with him to USDOT, including Mort Downey, who had been the Budget Committee’s original transportation analyst and who became Assistant Secretary for Budget and Programs at USDOT.

The new Budget Act had also set a ticking time bomb counting down in surface transportation. Up until that point, both the federal highway and mass transit programs were funded by multi-year contract authority provided in authorization acts. The highway contract authority was paid from the Highway Trust Fund, and the mass transit contract authority was paid from the general fund. A key feature of the Budget Act of 1974 was its ban on new “backdoor spending,” which included general fund contract authority. After the Budget Act was signed into law (but before it took effect), Congress enacted a huge lump sum of mass transit contract authority from the general fund in November 1974 that was supposed to be enough to tide transit programs through 1979, but after that, the program fell off a cliff. The future outlook for multi-year mass transit funding was uncertain.

Transportation was far from the top of President Carter’s agenda (aside from a handwritten note he sent Adams two months after his inauguration suggesting that new subway systems were a waste of money). The energy crisis and the struggling economy were front and center. In a January 24, 1977 outline of the Carter Administration legislative agenda for its first year, here is all that was said about transportation (the handwritten emphases were put there by Carter himself):

Starting in April 1977, Adams developed a plan to use some of the new energy taxes being discussed as part of the President’s energy plan as a “pay-for” for mass transit and railroad (principally Amtrak) grant programs that were currently being funded out of the general fund, which were totaling about $4.5 billion. In a memo to the President on July 15, Adams proposed putting the receipts from the tax increase, along with the existing Highway Trust Fund taxes, into a new “National Transportation Account” to cover highways, transit, rail and airport grant programs.

Adams wrote that one big multi-modal fund would “generate a secure funding mechanism broad enough to support not merely the narrow interest of any single mode, but the competing interests of all transportation modes” and would “jointly evolve an approach whereby major programs could be reviewed systematically, allowing broad considerations of trade-offs, relative needs and basic program merits to be assessed, rather than looking at highways one year, UMTA another, and railroads still another.

Carter’s advisors opposed Adams’ plan. White House energy czar Jim Schlesinger and the Treasury Department said that diverting the energy taxes to a specific program would damage the energy plan, and Stu Eizenstat, Carter’s domestic policy chief, was against dedicating any specific taxes to specific programs, stating that “Our experience with the Highway Trust Fund illustrates that such earmarking creates a floor rather than a ceiling on these public works investments.”

The House decided in late July 1977 to bring the energy tax bill to the floor and, unusually, they allowed certain amendments to be offered to the tax title of the bill. House Highway Subcommittee chairman Jim Howard (D-NJ) offered an amendment to increase the gas tax from 4 cents per gallon to 9 cents per gallon in order to pay for a transportation bill he wanted to write the following year. The 5 c.p.g. increase would be split in half, with 2.5 cents to the Highway Trust Fund and the other 2.5 cents to a new mass transit fund. Brock Adams notified President Carter the following day that “This will be very difficult to pass because there is substantial opposition to a gasoline tax on the Hill. Clear support for the 5¢ tax from the Administration could be a critical factor. Unless you have further instructions, I intend to stress that the Administration does in fact favor the House leadership position.” But a diffident Carter wrote “I prefer more flexible use of the money” on Adams’s letter.

When the bill (H.R. 8444, 95thCongress) reached the House floor (sans gas tax increases) in August, Howard offered the 5 c.p.g. gas tax increase split 50-50 between highways and transit (starting on page 26997 here). President Carter gave a somewhat tepid endorsement: “While I initially recommended a standby gasoline tax which would provide a specific disincentive on the wasteful use of gasoline, or a gasoline tax with greater flexibility for use of the revenues, I recommend positive action on this proposed tax which is supported by the House leadership.”

But Howard’s amendment – a surface transportation user tax in the context of energy legislation, not transportation legislation, and therefore lacking any guarantees of additional transportation spending – failed by a huge 82 to 339 margin. Then, Rep. Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL) offered another amendment that would have imposed a smaller, 4 cent per gallon gas tax increase, which failed by an even wider margin, 52 to 370.

By November 1977, Adams and DOT had developed a full-fledged highway and transit reauthorization proposal, which Adams forwarded to the Office of Management and Budget for clearance. By that time, Adams had abandoned his plan for one big multi-modal fund, but the unfunded nature of mass transit was still a problem, so Adams wrote to the President that:

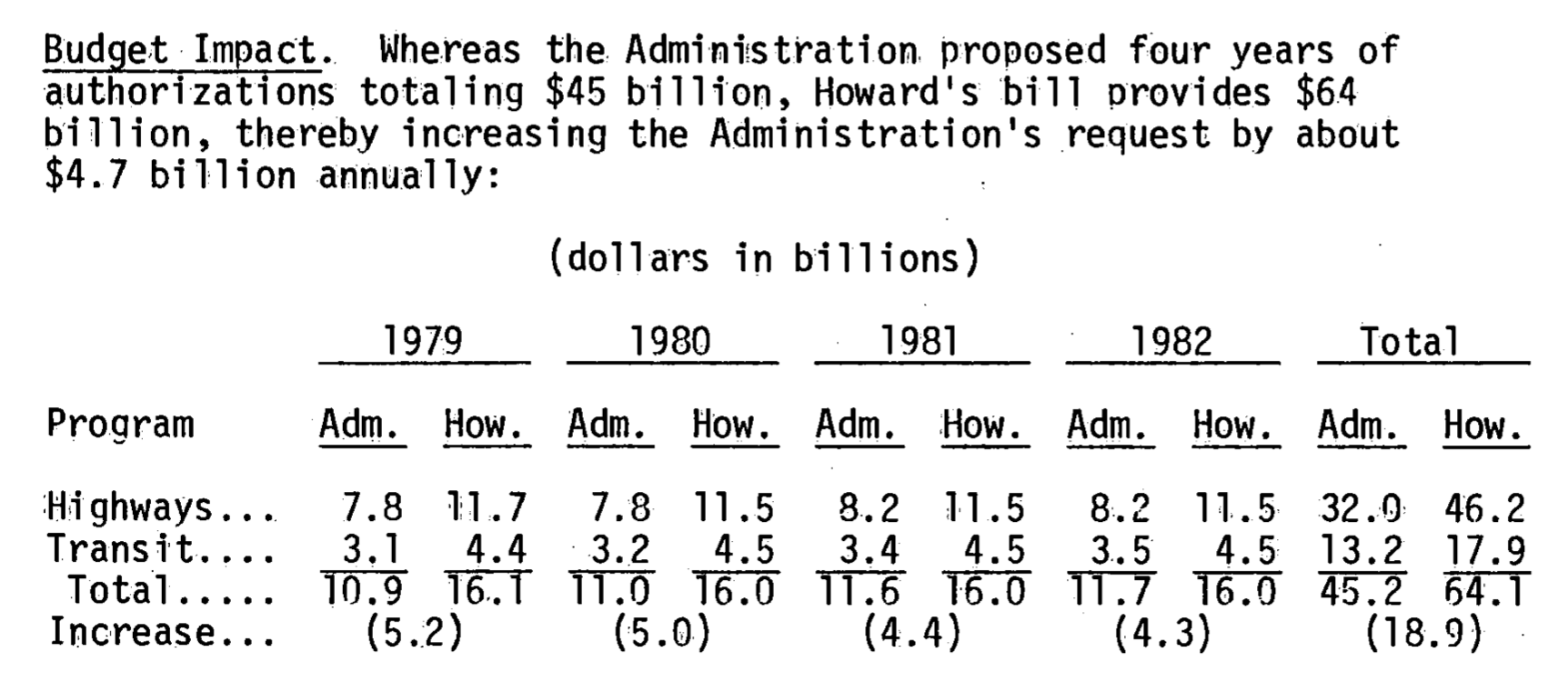

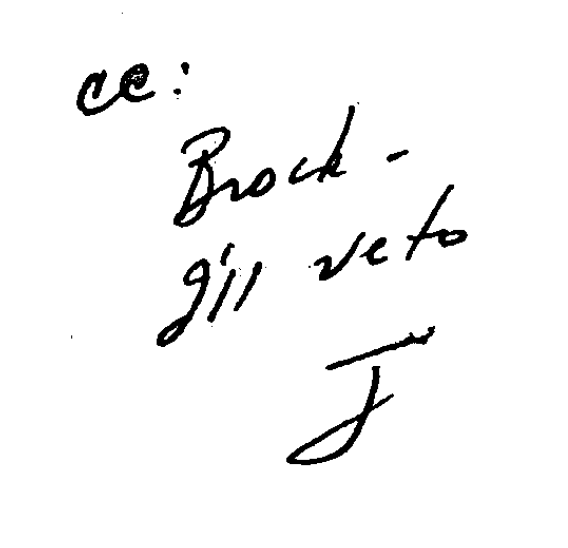

White House staff secretary Rick Hutcheson forwarded the OMB memo to Carter with a recommendation from the White House domestic policy staff that the veto threat come through Adams, not the White House, and suggesting that Carter mention the highway bill as one of the big-spending bills opposed by the White House in a forthcoming Presidential speech on inflation. President Carter forwarded the OMB memo to DOT after handwriting “Brock – I’ll veto” on the front page and “Let Brock take lead, Frank [Moore, the White House legislative liaison] to help” on the decision box page.

White House staff secretary Rick Hutcheson forwarded the OMB memo to Carter with a recommendation from the White House domestic policy staff that the veto threat come through Adams, not the White House, and suggesting that Carter mention the highway bill as one of the big-spending bills opposed by the White House in a forthcoming Presidential speech on inflation. President Carter forwarded the OMB memo to DOT after handwriting “Brock – I’ll veto” on the front page and “Let Brock take lead, Frank [Moore, the White House legislative liaison] to help” on the decision box page.