Looming Recession Sparks Familiar Calls for Infrastructure As Stimulus

The U.S. economy now appears headed into a recession – Bloomberg News noted yesterday, in the wake of the S&P 500 crossing the 20 percent drop threshold from its recent high, that such a drop has occurred 13 times since the index was initiated, and in 11 of those instances, the drop was accompanied by an economic contraction over the next year. And, predictably, there are those in Congress who are calling for an increase in federal infrastructure spending as part of a response to this downturn in the business cycle.

Of course, any fiscal stimulus that Congress that Congress takes by increasing federal spending or decreasing federal taxes will pale in size and immediacy to what the Federal Reserve can do (and is already doing) with monetary policy, both conventional (lowering interest rates) and unconventional (putting $1.5 trillion in cash into the overnight repo markets). Fiscal policy is important, as well.

But is increased infrastructure spending the best way to counter a downturn in the business cycle that is caused by the confluence of a (a) a reduction in foreign trade; (b) a temporary collapse in demand for travel, hospitality, and public gatherings, and (c) a drastic drop of oil prices and its effect on the energy sector?

Let’s look at history.

The 2009 ARRA experience. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of February 2009 (P.L. 111-5) put some $26.7 billion of its estimated $787 billion in fiscal stimulus in the form of highway formula grants to states and the District of Columbia. This money was:

- Appropriated from the general fund, not the Highway Trust Fund;

- Given to states at a 100 percent federal cost share, eliminating the need for the standard state matching share of up to 20 percent of a project’s cost;

- In addition to the $34.4 billion in formula funding from the Highway Trust Fund provided for FY 2009;

- Subject to redistribution from the original apportionment if any state did not obligate certain percentages within 120 and 365 days of the original apportionment;

- Required to be legally obligated in its entirety by September 30, 2010 lest it lapse; and

- Subject to 31 U.S.C. §1552, which required that every dime of the obligated money be spent (outlaid) by September 30, 2015, or else it would vanish.

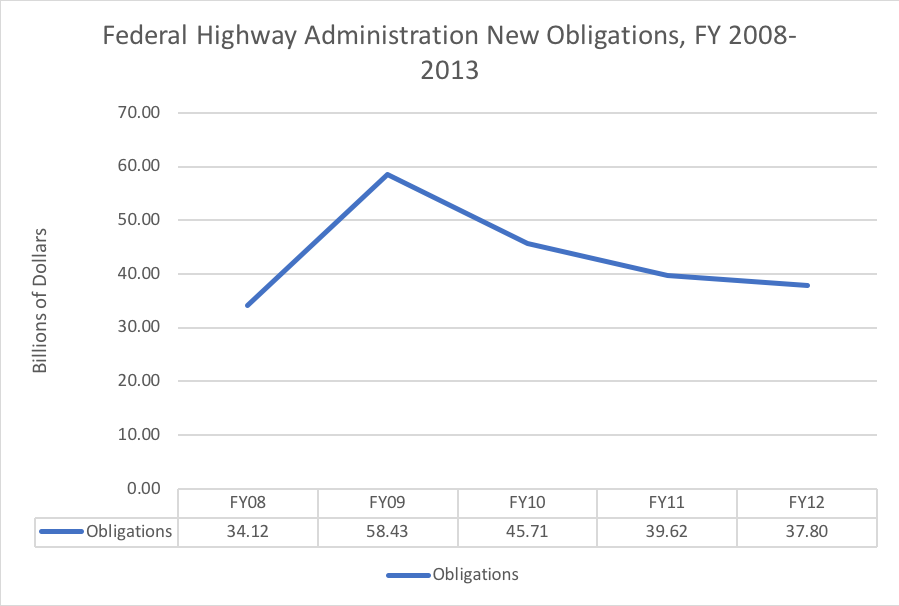

Once the states had received the money, they did indeed obligate all that money, and quickly, too. The following table shows all (formula and non-formula) obligations of FHWA funding, excluding territories and FHWA overhead, per the Table FA-4B series in Highway Statistics, and FY 2009 obligations incurred were $24.3 billion above the 2008 level.

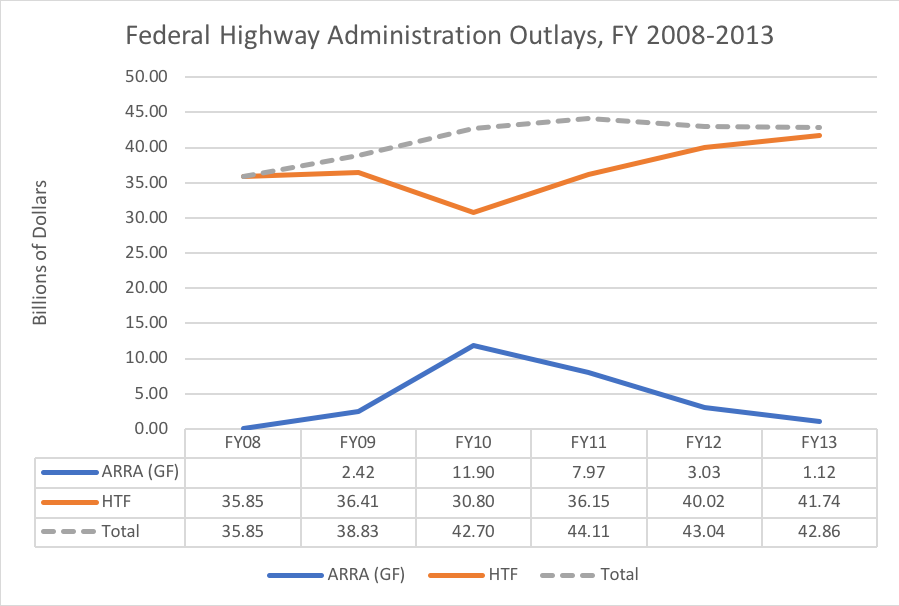

However, when you look at cash going out the door of the Treasury (outlays), the situation looks very different. The actual spending increased much more slowly, and it is clear that in 2010 and 2011, general fund ARRA spending largely replaced – not supplemented – regular Highway Trust Fund spending. (Other general fund spending on emergency relief and the $650 million in 2010 GF formula money are not shown).

Why the discrepancy? There are only so many highway contractors in each state, and only so many state DOT engineers to supervise the projects. And in a lot of states there are just not enough “shovel-ready” projects ready to go on short notice. Faced with hard obligation and outlay deadlines for the ARRA money, a lot of states prioritized projects like resurfacing existing roads so that the ARRA money could be spent on time, while delaying larger projects with longer-term impact to fund with Highway Trust Fund dollars once the ARRA money had been committed.

There was some additive effect – 2011 in particular – but at the peak in 2010, Trust Fund outlays dropped by $5.6 billion from the prior year, negating much of the $9.5 billion general fund outlay increase over the previous year.

The Congressional Budget Office recently published a review of economic literature on the subject, finding that “In most of the literature, researchers studying federal grants for highways have found that state and local governments reduce highway spending from their own funds as federal grants increase. However, less consensus exists over the magnitude of that substitution effect, with a range of effects estimated.” (The range is wide indeed: “For an increase of $1 in federal grants, most estimates suggest, state and local governments would reduce spending on highways from their own funds by between $0.20 and $0.80.”)

Previous attempts at highway stimulus. In the more distant past, Congress tried another way to use federal highway spending as counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus. Instead of apportioning new federal dollars on top of existing dollars, they simply lowered or eliminated the matching share of money that states were required to put up in order to spend existing highway dollars. In 1958, Congress temporarily increased the federal share on some highway funds from one-half to two-thirds of a project (almost prompting President Eisenhower to veto the bill).

Then, in February 1975, January 1983, and October 1991, Congress fought economic downturns by temporarily increasing the federal share of many projects to 100 percent. In all four cases, the increased federal share was temporary, and in all cases, it was a temporary loan of funding from the federal government to states – once the economy had improved, the states were expected to pay the money back.

| PREVIOUS TEMPORARY WAIVERS OR REDUCTIONS OF STATE MATCHING SHARES OF FEDERAL-AID HIGHWAY PROJECTS | |||||

| Public | Temporary | ||||

| Year | Law | Sec. | Fed. Share? | Duration? | Repayment to Federal Government By? |

| 1958 | 85-381 | 2 | Two-thirds | 4/16/1958-11/30/1958 | Automatic deduction from FY 1961 and 1962 apportionments. |

| 1975 | 94-30 | 1, 2 | 100 percent | 2/12/1975-6/30/1975 | States pay back the HTF by 1/1/1977 or else face “death penalty.” |

| 1983 | 97-424 | 145 | 100 percent | 1/6/1983-9/30/1984 | States pay back the HTF by 9/30/1984 or else face automatic deduction from FY 1985 and 1986 apportionments. |

| 1991 | 102-240 | 1054 | 100 percent | 10/1/1991-9/30/1993 | States pay back the HTF by 3/30/1994 or else face automatic deductions from FY 1995 and 1996 apportionments. |

What is “stimulus” anyway? Infrastructure spending is a subset of capital spending, and the whole point of capital spending is that it spends much more slowly than salaries and other operational spending, but it buys things that have a permanence (whereas operational spending is transient).

The slowness of capital spending makes it a poor fit to counter any short-term downturn in the business cycle (and right now, it is unclear if the coronavirus-instilled part of this will be a short, sharp shock or a signal of something longer-term). Operational spending as a counter-cyclical remedy is a different matter, as its effects are felt more immediately and more widely.

But increasing capital spending in general, and infrastructure spending in particular, is something that all levels of government probably need to be doing anyway (if well targeted to the projects that provide the greatest long-term benefits). And it’s the federal government that owns the printing presses that print Planet Earth’s reserve currency, not state or local governments.

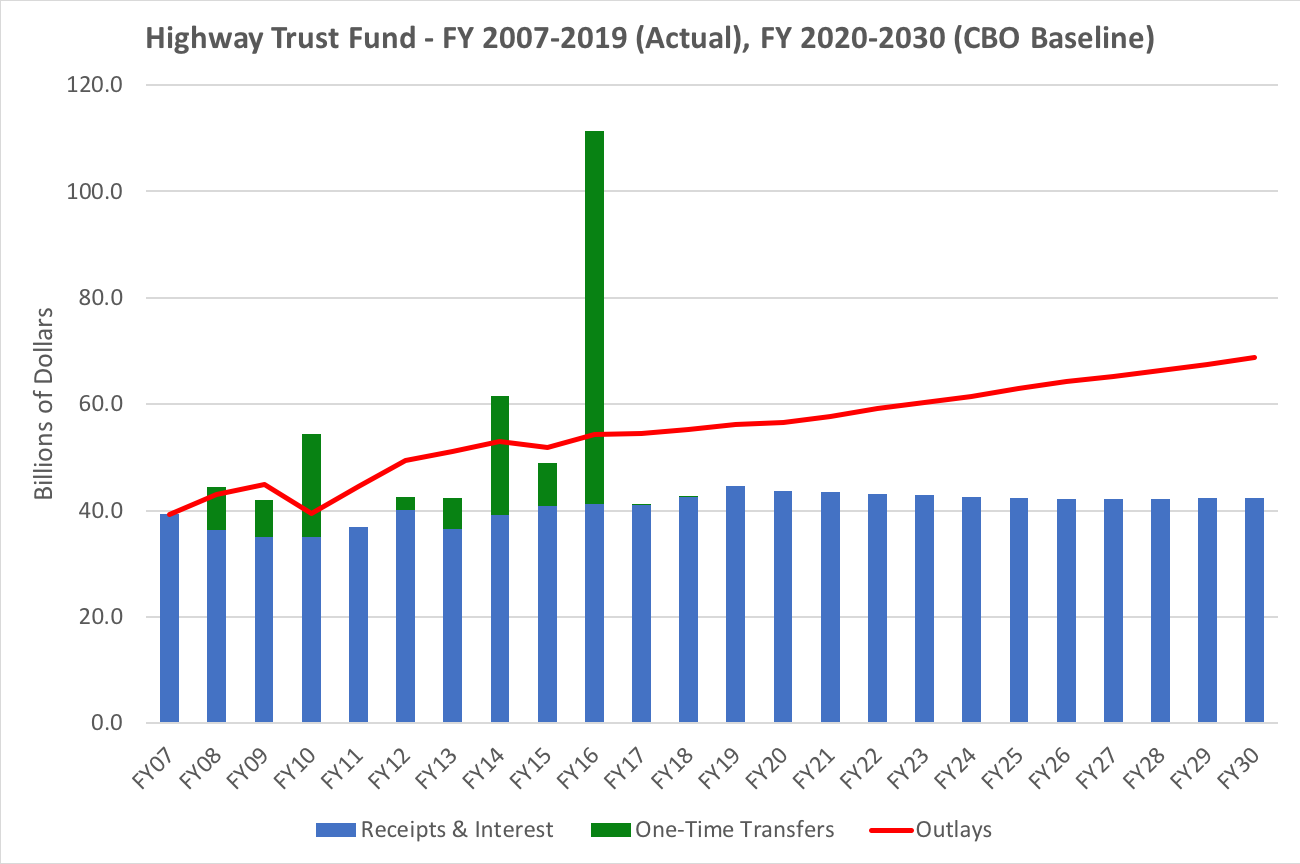

So, in the current situation (as in the 2009 ARRA situation), it’s not just a question of new spending, it’s also a question of whether or not we should pay for the spending that is already taking place. And, when it comes to surface transportation infrastructure spending, most of that money is currently coming from a Highway Trust Fund that is only partially solvent and which has required $143 billion in bailouts over the last decade to stay solvent. Here is the nifty chart we came up with to show the 2008-2019 actual period, and the CBO baseline projections for 2020-2030 at the 2020 spending levels plus annual inflation:

All the green columns together add up to the $143 billion in Trust Fund bailouts since 2008, and the tallest green column is the $70 billion bailout from the December 2015 FAST Act, which will be spent out by late summer 2021. From then on, the gap between the blue columns of tax receipts and the red line of outlays will have to be met with decreased spending or increased tax revenues (or more bailouts). If you assume that end-of-FY21 is a zero balance just for rounding purposes, here is what the CBO current-spending-plus-inflation baseline says the annual Highway Trust Fund cash deficits will be through 2030:

| FY22 | FY23 | FY24 | FY25 | FY26 |

| -$16.1 B | -$17.6 B | -$18.8 B | -$20.6 B | -$21.9 B |

| FY27 | FY28 | FY29 | FY30 | Total |

| -$23.0 B | -$24.1 B | -$25.3 B | -$26.4 B | -$194 B |

Decreasing spending is difficult because Congress only has control over the rate of new spending obligations (not outlays, which are the eventual dollars leaving the Treasury to fulfill obligations and they occur at their own pace). For a new highway obligation, only 25 percent of the outlays occur in the first year (on average), and for mass transit formula obligations, only 15 percent of the outlays occur in the first year. So if you want to cut Highway Trust Fund outlays in 2021 by $2 billion, you need to cut new FY 2021 obligations by around $9 billion to do so.

Cutting that spending will take money out of the economy. So will increasing highway user excise taxes. And so will paying for a general fund bailout transfer to the Trust Fund (if you decide to pay for that transfer at all). There is widespread economic consensus that pulling government spending out of the economy is bad during a recession, as is increasing taxes during a recession.

So, for highway and transit programs that, coincidentally, are up for reauthorization by Congress as this recession is getting started, paid for by a Trust Fund that will go broke and need bailing out just as the economy is starting to recover in earnest next year, the question isn’t whether or not to maintain or increase current spending. The question is whether to pay for current and increased spending, or just go ahead and finance it through general fund deficit borrowing in the name of not making the recession worse.

You can expect some people to propose that, in the name of not exacerbating the recession, we simply postpone the eventual reconciliation of the $50+ billion per year in annual Highway Trust Fund outlay trend line with the circa $40 billion per year in Trust Fund excise taxes trend line, and just go ahead and do another Trust Fund bailout transfer from the general fund, paid for by borrowing from the bond markets. This transfer would have to be at least $103 billion (to pay for the Senate’s five-year bill), somewhere north of $150 billion (to pay for the House’s five-year bill), or somewhere around $270 billion (to pay for the White House’s ten-year bill).

Because of a budget loophole, these bailout transfers don’t actually show up in the budget as spending, so it won’t add to the CBO/OMB score of any stimulus legislation – but implicitly, those transfers (when spent) are paid for by general government borrowing. And a massive preemptive bailout would allow surface transportation reauthorization to take place on time without the political problems of having to raise taxes while staring down a recession, or dealing with a highway-transit split of highway user tax revenues that has become unsustainable, or dealing with “donor state” concerns.

Make no mistake – simply bailing out the Trust Fund once more from general revenues would be terrible trust fund policy – the primary justification for the existence of trust funds is to correlate special taxes on one group with spending from special programs that give disproportionate benefits to that group, in a transparent way, so making general revenues fungible with user tax revenues destroys that transparency and kills the rationale for trust funds. But that patient died $143 billion ago, after the first bailout in September 2008. If policymakers won’t reconcile user tax payments with spending that benefits those users, the honest thing to do would to abolish the Trust Fund and put highway and transit spending decisions through the same tests as housing, environmental, veterans, law enforcement, national defense, health, and other spending decisions.

But, because honesty is a currency in short supply these days (and deficit spending is not), and because a looming recession adds a policy reason not to raise taxes (the politics of which was always going to be painfully difficult), maybe the answer is just to give up on the highway user-pay charade, do a massive up-front bailout immediately, then write a reauthorization bill and get it enacted by September 30 to avoid the disruptive effect that funding uncertainty has on states.

(A more fiscally responsible answer would be to pass a reauthorization bill with one last general fund bailout to get through the end of the recession, and then a 20 or 25 cent gasoline/diesel tax that is phased in via five-cent annual increments, to take effect only when BEA or somebody declares the recession over. But then Congress would probably just keep delaying the implementation of those gas tax increases, like the 2010 “Obamacare” law’s medical device and Cadillac health care plan taxes (which were set to take effect a few years after enactment, kept getting delayed and then eventually repealed outright in December 2019) and bailing out the Trust Fund from general revenues once more.)

If Congress and the President are eventually going to take the path of least resistance that continues to get farther and farther away from the user-pay, user-benefit rationale for the Highway Trust Fund, they might as well just go ahead and get it over with now.

The views expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Eno Center for Transportation.