If you follow transportation Twitter, you may have noticed the hashtag #SaveTransit making the rounds this week, as advocacy groups tried to press Congress to appropriate another $32 billion (at least) for mass transit COVID-19 relief in the next COVID relief bill. This would be in addition to the $25 billion appropriated for transit in the CARES Act back in March of this year.

Now that the Congress has adjourned without taking further action on a COVID bill, and no action is expected until at least the week after Labor Day, we can take time to put the enacted $25 billion in relief, and the proposal for $32 billion more, in broad perspective.

Replacing lost passenger fares. The primary justification for giving mass transit its own aid package in mid-March (separate from the larger issue of general-purpose federal aid to state and local governments) was the immediacy of the passenger fare problem. The day that a person stops taking mass transit, the money that person would have paid to ride will no longer go into the transit provider’s coffers. The effect on transit agency cash flow was immediate (unlike other forms of financial support for transit agency operations, changes to which can take much longer to be felt).

In addition, the COVID precautions taken by providers often meant that, even when someone still took mass transit, fares were temporarily going uncollected.

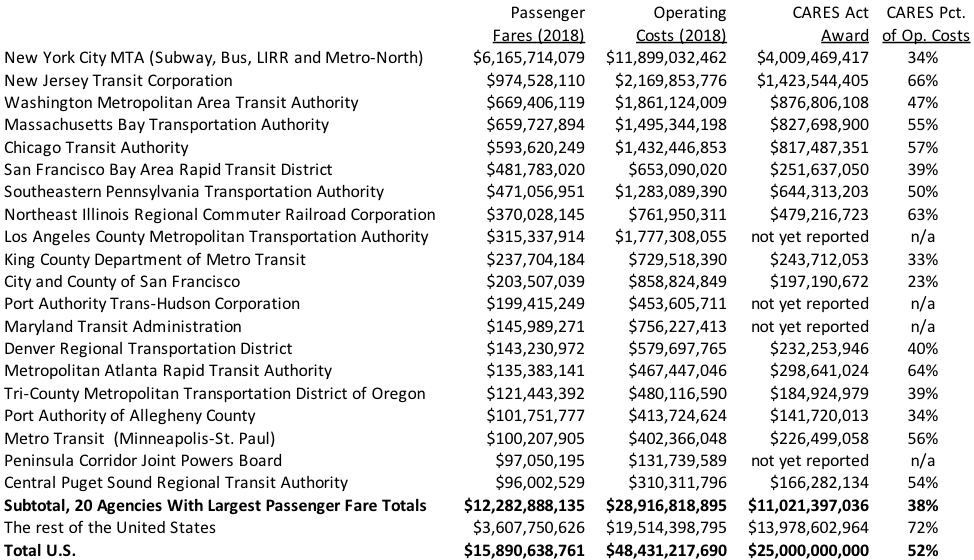

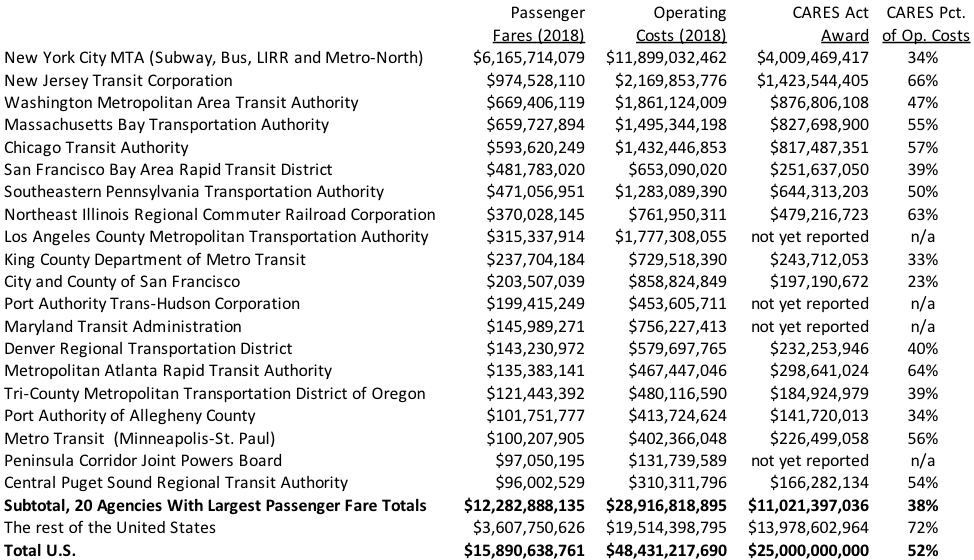

How big was the CARES Act’s appropriation in this context? Well, if the problem being addressed was simply a matter of lost farebox revenues, the latest National Transit Database tells us that the sum total of all passenger fares paid in the year 2018 was $15.9 billion. So the CARES Act replaced enough lost fare money to equal every dime paid by every mass transit user in the U.S. for about a year-and-a-half of normal (pre-COVID) transit ridership.

25 plus 32 equals 57. If Congress enacts a $32 billion package of additional transit aid, on top of the CARES Act appropriation, this $57 billion would equal all mass transit passenger fares paid by every transit user in the U.S. for 3.6 normal years. So, if everyone in America abandoned mass transit on March 15, 2020, and not a single living soul paid to ride mass transit again until October 2023, $57 billion would cover all of the lost farebox revenue for those 43 months.

Covering operating costs. Of course, even in normal times, passenger fares don’t come close to covering all operating costs. Nationwide, in 2018, the NTD tells us that passenger fares covered one-third of operating costs. This varies widely by agency – San Francisco BART had a 74 percent farebox recovery rate in 2018, and the New York City MTA recouped a little over half of its operating costs from fares. The DC-area WMATA recovered 36 percent, and Los Angeles County only 18 percent (which was the national average if you remove the 20 agencies with the largest amount of fares raised in 2018). State and local governments make up the rest of the money (with some non-fare recovery like advertisement sales and real estate leases added in).

Total operating costs for all mass transit in the U.S. in 2018 totaled $48.4 billion. A new $32 billion appropriation, on top of the $25 billion already appropriated, would be enough to pay for all U.S. mass transit operations for 14 months, without transit agencies or state or local governments having to spend a dime of their own money. So, with the COVID crisis getting serious in mid-March 2020, CARES plus $32 billion means zero net operating costs for transit agencies, or state and local governments, from that point through May 2021.

(Transit agencies were incurring some unanticipated costs due to coronavirus (PPE purchases, overtime needed for frequent cleaning of vehicles, etc.). But these costs have, to some extent, been offset by savings in reduced frequency of service. Some transit agencies are trying to solve the revenue loss and decreased demand problems with employee layoffs or furloughs, which probably isn’t a sound long-term strategy. We don’t have any solid numbers on the overall effect of COVID on total operating costs. On an agency-by-agency basis, we use the best data we have, which are the 2018 NTD numbers.)

Timeframe. The request for $32 billion appears to conflate immediate needs with longer-term needs. No one denies that many transit agencies are having extreme revenue crises. The San Francisco Muni system and the New York City MTA, in particular, are burning through their CARES Act grants and are close to spending their entire allotment (if they haven’t already). As new federal data reported last week, however, many major transit agencies had not yet spent significant amounts of their CARES Act money as of June 30.

Mass Transit magazine covered the July 14 APTA press conference organized around the $32 billion request (which was up from APTA’s $24 billion ask in early May and appears to be based on New York City MTA’s analysis of nationwide needs, not APTA’s survey of its members). The Mass Transit article reported that, among the justifications for the $32 billion in additional federal aid given at the press conference, were “$500-$800 million loss through Fiscal Year 2023 for the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA)” and “Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) is facing a deficit of $975 million over a three-year period, which includes $40 million per month in lost passenger revenue.”

Do hypothetical revenue problems that transit agencies may face in 2023 really need to be in the same discussion about other transit agencies running out of money in the next two to three months? In particular, at this moment we still don’t know if the outcome of the COVID problem will be “vaccine readily available in early 2021” or “no vaccine, ever.” The effect of COVID on mass transit finances in 2022 and 2023 is still fundamentally unknowable because we have no idea whether we will wind up closer to the optimal vaccine scenario or to the no-vaccine-ever scenario.

How should future funding be distributed? The CARES Act’s $25 billion was a little more than half a year’s nationwide mass transit operating expenses. But because of the formula that was used, each provider’s share of operating costs offset by CARES grants varied widely. If you subtract the 20 or so largest providers, CARES grants averaged to be over 70 percent of the total remaining national $11.9 billion 2018 in operating costs. But the New York City MTA’s $4 billion CARES grant was only equal to 34 percent of its 2018 operating costs. Across the river, New Jersey Transit’s $1.4 billion CARES grant was 66 percent of its $2.2 billion in operating costs. Chicago-area’s Metra and Atlanta’s MARTA also got CARES grants equal to almost two-thirds of a year’s operating expenses. But San Fran Muni’s $197 million CARES grant was only 23 percent of its $859 million annual operating costs.

Is it any wonder, then, that NYC MTA and San Fran Muni have been spending their CARES grants a lot faster than other major transit agencies?

APTA has requested that the bulk of its $32 billion request not be distributed by formula – instead, the Federal Transit Administrator would distribute the funding based on demonstrated need. The eye-of-the-beholder nature of discretionary programs like this usually makes Congress leery, which is why Congress prefers to use formulas so that they know how much money the providers in their state or district are guaranteed before they vote to provide the money.

The CARES Act used a blend of existing formulas designed to spread money widely while also giving New York City the minimum dollar amount they said they needed at the time. It was that blend of formulas that led to the large discrepancies in operating costs being offset by CARES.

The House-passed Heroes Act would have given out most of its $16 billion via formula – but would have confined that formula aid to the 14 largest metro areas, leaving cities like Denver, Baltimore, and transit-loving Portland swinging in the wind, as our analysis noted.

If Congress is going give out another round of emergency funding to transit agencies, and insists on a formula so they know how the money will be distributed in advance, perhaps operating costs should be the prime driver of the formula. Ideally, Congress could give out the next round of aid to providers (not to metro areas, which often have many providers – the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim metro area has dozens of providers), based on their most recent annual operating costs in the National Transit Database (2018) minus the amount of their CARES grant. Giving every provider a fixed total share of a year’s operating costs (CARES plus whatever comes next) seems to solve the problem of some providers (especially small ones) getting much more money than they need to function, while other agencies are still going broke.

However, true fairness in covering each provider’s operating costs raises another problem.

The New York City problem. The Big Apple is the only place in the U.S. where mass transit really works – it functions the way that transit functions in other megalopolis peer cities in Europe and Asia, and the city literally cannot function without it (no possible work-around). This is because NYC has the density and the demand. Per the National Transit Database, in the U.S. in 2018, there were 9.86 billion unlinked passenger trips on mass transit, and the NYC MTA had 3.70 billion of them – 37.6 percent. In terms of mass transit passenger-miles, out of a national total of 54.06 billion, NYC MTA hosted 17.66 billion of them – 32.7 percent. And this does not even count PATH trains or the large share of New Jersey Transit passengers going in and out of NYC.

This has always been a political problem for the federal mass transit program – Congress is used to funding programs that spread benefits broadly across the United States, but when it comes to mass transit, New York City is so big, and its needs so unique, that it is almost impossible to write a formula that meets NYC’s needs and those of the rest of the nation, if the overall dollar amount of the program is constrained in any way (as it always is). (Remember that the NYC MTA actually quit APTA in April 2016 before rejoining two years later – there were many reasons for this, not all policy-related, but one of the underlying problems was the difficulty in writing federal transit policy proposals that make sense for NYC but also for the smaller, bus-centric transit agencies outside the very largest metro areas.)

A focus on operating costs in any future COVID funding would inevitably give NYC an extremely large share of the next round of funding – more than Congress might feel comfortable with. For example, under the CARES formula, the NYC MTA’s grant was 4.8 to 4.9 times bigger than the grants to Chicago (CTA) or Boston (MBTA). If the next round of grants were to be given out based on operating costs, and with the earlier CARES grants subtracted from those operating costs, then the NYC MTA’s grant out of the next round of COVID funding would be 12 or 13 times the size of Chicago’s or Boston’s grants (since those cities got CARES grants equal to 55 and 57 percent, respectively, of their 2018 operating costs, while the MTA only got 34 percent of its operating costs).