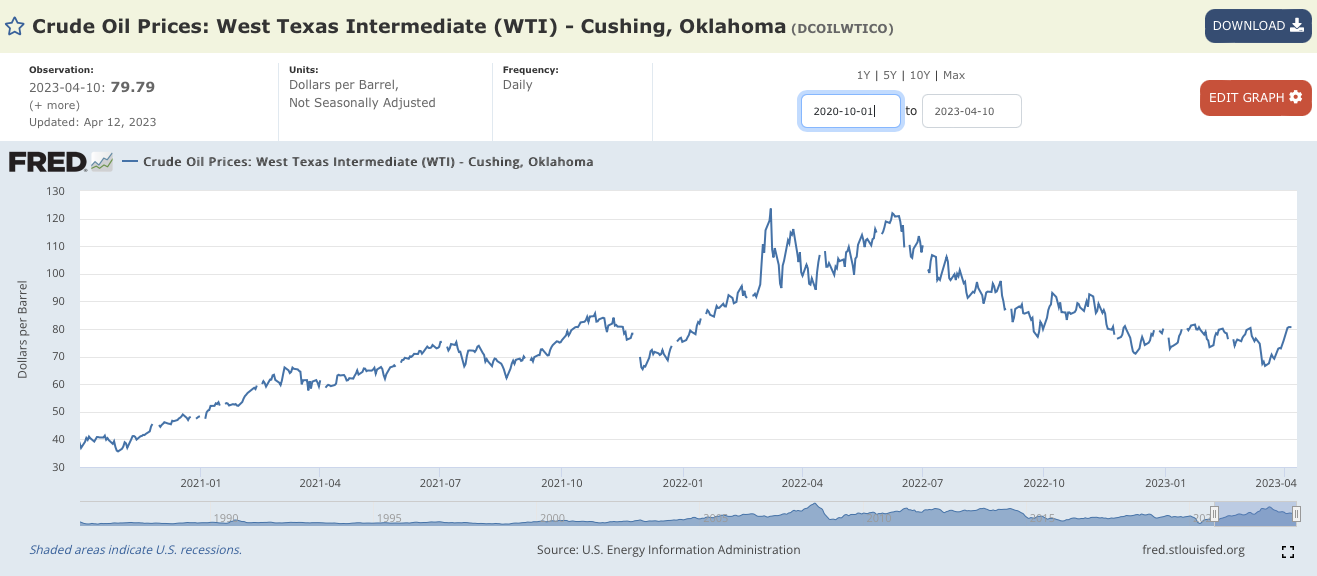

(Also, even if and when petroleum gets cheaper, at some point the added money from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) will test the capacity of steel mills, cement kilns, and gravel pits to produce materials in sufficient quantities to meet increased demand without more price increases, to say nothing of demands of labor for increased wages in a tight labor market.)

For years, we have tried to figure out the best measure of the lost buying power of federal dollars. When it comes to spending, the easiest thing to track is outlays, which are the cash dollars leaving the Treasury as they are transferred via check or wire to non-federal entities. These are reported monthly by the Treasury. But these outlays are usually paying off contracts which were signed months or years before, so they don’t really measure the effect that price increases have on newly signed contracts.

Fortunately, in 2017, usaspending.gov went online and lately it has gotten so user-friendly that it can be used to track obligations as well as outlays – not by month, but by by quarter. Obligations are the best proxy for contracts being signed (an obligation is recorded when FHWA approves a project agreement and commits a specific amount of federal dollars for a specific project).

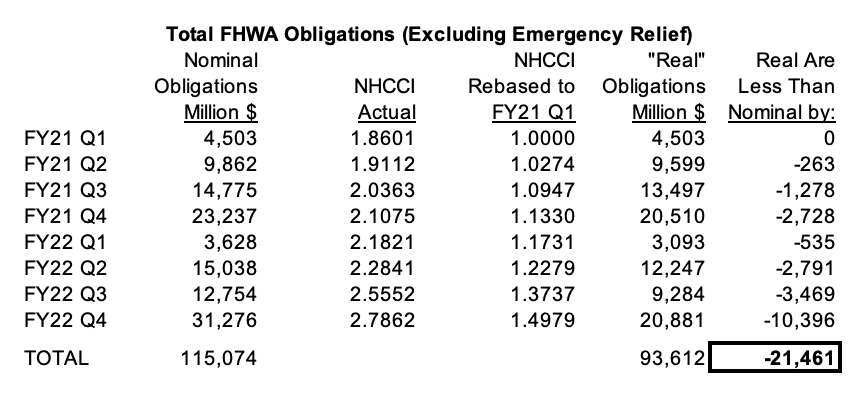

We added up the total obligations in each quarter for the two major FHWA budget accounts (the Federal-Aid Highways account (8083), which is all their spending from the Highway Trust Fund, and the Highway Infrastructure Programs account (0548), which is all of the general fund plus-ups from the regular appropriations bills combined with the IIJA advance appropriations from the general fund). This excludes periodic Emergency Relief appropriations.

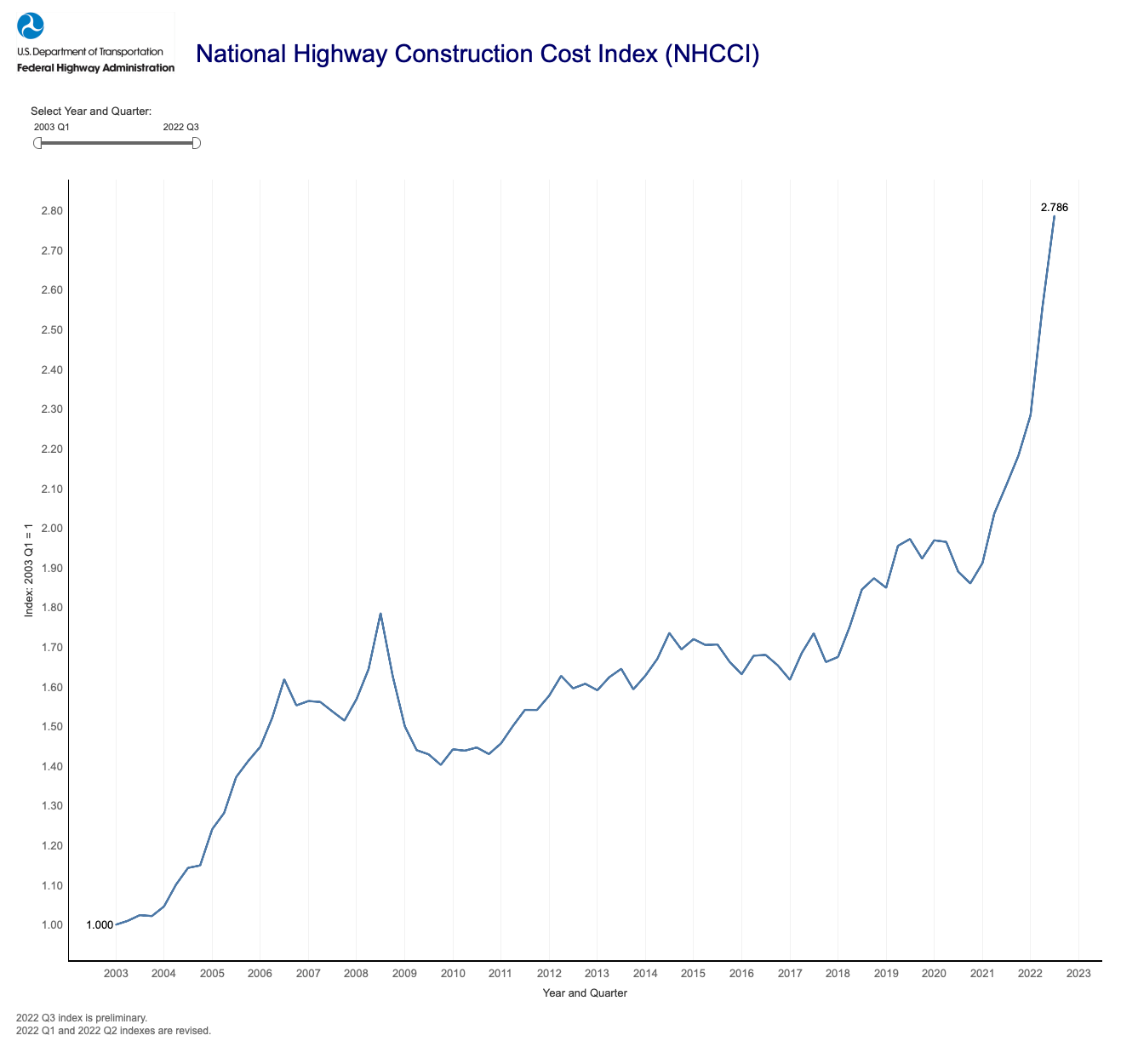

Then, we re-based the NHCCI to start at the last low point on the chart above (Oct-Dec 2020) and deflated the obligation totals by dividing the nominal obligation totals by the rebased index number. The result is “real” buying power of those obligations, after removing the highway cost inflation since the end of 2020.

We calculate that federal highway spending has lost $21.5 billion in buying power since the end of 2020.