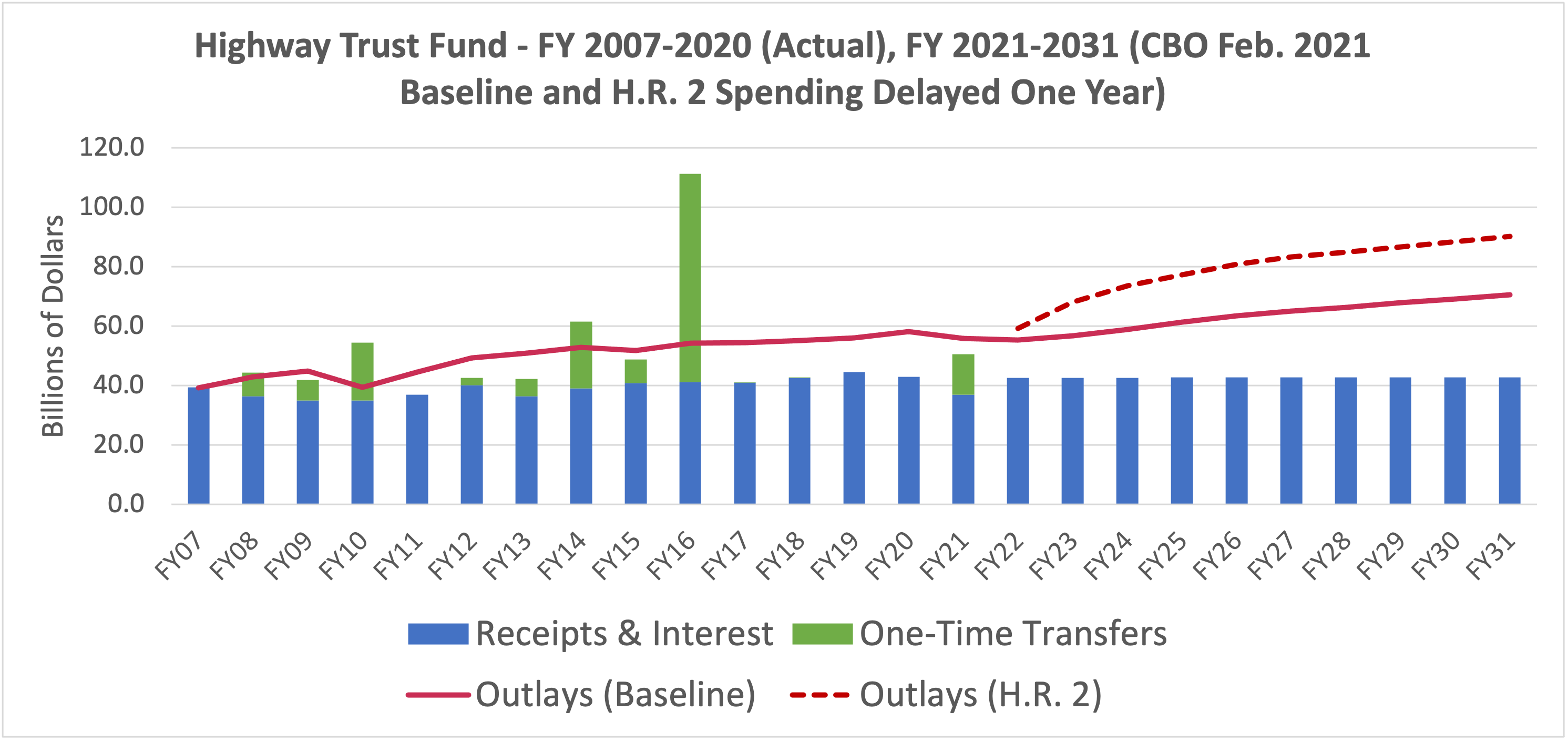

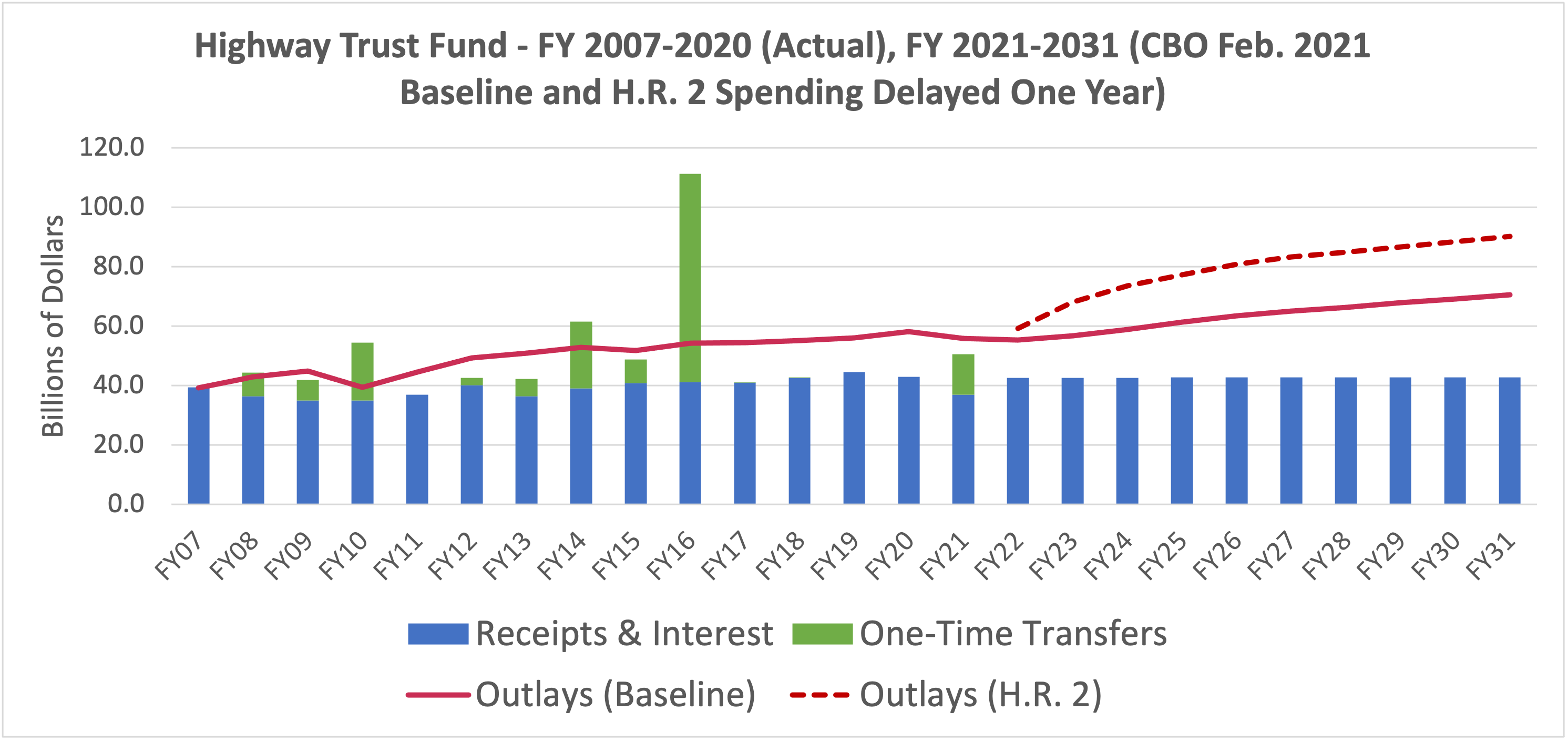

Surface transportation reauthorization legislation is due from Congress this year, and increased investment in infrastructure of all kinds seems to be in the air. But the financial mainstay of surface transportation funding, the Highway Trust Fund, has been insolvent since 2008 and has been propped up by frequent bailout transfers from general revenues. The big infrastructure bill passed by the House last year (H.R. 2) would have significantly increased spending from the Trust Fund, paid for with another giant bailout, which would have made the long-term insolvency of the Trust Fund much worse.

The following chart shows the last 13 years of the Trust Fund (actual cash flow) compared with the current law baseline projections for the coming decade, as well as the extra funding that H.R. 2 would provide if you simply move all of its authorizations forward one year (last year’s FY 2021 authorizations become this year’s FY 2022 authorizations, etc.). The systemic imbalance between user tax receipts and spending continues to grow and grow.

So far, there does not appear to be the political will in D.C. to increase highway user taxes, and that lack of willpower starts with the White House (which, historically, always has to take the lead on unpopular tax increases in order to get them enacted). Worsening the HTF’s systemic balance seems like the most politically likely outcome.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, even if the will to raise highway user taxes doesn’t manifest anytime soon.

A Perpetual Trust Fund. The Trust Fund could, conceivably, be put on autopilot and be self-sustaining indefinitely. All one has to do is get rid of the current system of authorizing fixed amounts of contract authority for each fiscal year, and put into place statutory language that automatically creates as much new contract authority each year as was actually deposited in the Trust Fund from tax receipts and interest the year before.

This would mean that each year’s new contract authority would not become available until, say, November 1 or December 1 instead of October 1 (since it takes a few weeks after the close of the fiscal year for Treasury to close the books), but that’s not really a big deal for capital grant programs (you would have to shift FHWA and FMCSA salaries from contract authority to the regular budget or find some other work-around for them, but otherwise, states and transit agencies won’t really notice the delay so long as they have certainty the money is coming).

This would also require one last big bailout from the general fund to pay for the “transition costs” of getting unsustainable spending back down to a sustainable level. But there would never have to be any more bailouts after that.

At current revenue levels, the Trust Fund could support $35 billion or so per year in Highway Account spending and $5 billion or so per year in Mass Transit Account spending, forever (plus amounts subsequently “flex” transferred from highway to transit). But part of the beauty of the Perpetual Trust Fund is that, if a subsequent Congress does find the nerve to increase highway user taxes, the money raised by those tax increases would automatically be given to states and transit agencies and spent, the year after the taxes are received.

But, without a massive and immediate highway user revenue increase, this system will still need extra spending from somewhere else to supplement the $40 billion per year in Perpetual Trust Fund money in order to meet and exceed today’s spending levels.

Separate time frames (how Eisenhower did it). We hear a lot of nostalgia about how the current generation is coasting on Eisenhower-era infrastructure. True to some extent, but there is one key thing that Eisenhower did on infrastructure, specifically highway infrastructure, that we no longer do today, and that is to give out money under multiple time horizons. Once the decision had been made to marry the proposed new Interstate Construction program with the regular Federal-aid Highway program, and authorize them in the same bill in 1956, Congress and the President decided to provide some highway money on a very long timeframe (up to 13 years in advance), and provide other highway money on a short timeframe (two years in advance). Those two separate schedules were updated over and over, until they gradually synced back up as the final Interstate Construction money was provided in ISTEA.

| Highway Contract Authority Provided in Advance by Authorization Acts |

|

|

Contract Authority Provided For… |

| Act |

Enacted |

Interstate Construct. |

Regular Program |

| 1956 FAHA |

June 29, 1956 |

13 (FYs 1957-1969) |

2 (FYs 1958, 1959) |

| 1958 FAHA |

April 16, 1958 |

No new years |

2 (FYs 1960, 1961) |

| 1960 FAHA |

July 14, 1960 |

No new years |

2 (FYs 1962, 1963) |

| 1961 FAHA |

June 29, 1961 |

2 (FYs 1970, 1971) |

None |

| 1962 FAHA |

Oct. 23, 1962 |

No new years |

2 (FYs 1964, 1965) |

| 1964 FAHA |

Aug. 13, 1964 |

No new years |

2 (FYs 1966, 1967) |

| 1966 FAHA |

Sept. 13, 1966 |

1 (FY 1972) |

2 (FYs 1968, 1969) |

| 1968 FAHA |

Aug. 23, 1968 |

2 (FYs 1973, 1974) |

2 (FYs 1970, 1971) |

| 1970 FAHA |

Dec. 31, 1970 |

2 (FYs 1975, 1976) |

2 (FYs 1972, 1973) |

| 1973 FAHA |

Aug. 13, 1973 |

3 (FYs 1977-1979) |

3 (FYs 1974-1976) |

| 1976 FAHA |

May 5, 1976 |

11 (FYs 1980-1990) |

2 (FYs 1977, 1978) |

| 1978 FAHA |

Nov. 6, 1978 |

No new years |

4 (FYs 1979-1982) |

| 1982 STAA |

Jan. 6, 1983 |

No new years |

4 (FYs 1983-1986) |

| 1987 STURAA |

April 2, 1987 |

3 (FYs 1991-1993) |

5 (FYs 1987-1991) |

| 1991 ISTEA |

Dec. 18, 1991 |

3 (FYs 1994-1996) |

6 (FYs 1992-1997) |

| Starting with the 1998 TEA21 law, there was no more Interstate Construction funding, and all authorizations in the act covered the same time period. |

It would be interesting to see a survey of state DOTs and transit agencies and have them answer the following question: would they rather have a core amount of Trust Fund money guaranteed for a decade (or longer), supplemented every few years with a less predictable amount of extra money, or would they rather have the current system where none of their money is guaranteed longer than 4-5 years in advance and the Trust Fund is perpetually insolvent and could conceivably shut down at the end of each bill and cut off their reimbursement cash flow if the political winds blow the wrong way?

Although, under Ike, both time frames of highway money were paid out of the Highway Trust Fund (except for forest roads and some odds and ends), there is no reason that all the money has to be from the same source.

If not from the Trust Fund, then… One option is to look at just providing massive amounts of real money out of general revenues. Real money means budget authority (not another intragovernmental transfer into the Highway Trust Fund), and in this case, it means the general fund. Imagine the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee supplementing the $35 billion or so per year that a Perpetual Trust Fund would provide for highways with the following section in a reauthorization bill:

There shall be made available, in addition to any other funds made available, to carry out Federal-aid highway and highway safety construction programs authorized under titles 23 and 49, United States Code, to remain available until expended: (a) $24,000,000,000 to become available on October 1, 2021; (b) $25,000,000,000 to become available on October 1, 2022; (c) $26,000,000,000 to become available on October 1, 2023; (d) $27,000,000,000 to become available on October 1, 2024; and (e) $28,000,000,000 to become available on October 1, 2025.

As written, that would be real money. (It doesn’t have to have the words “appropriation” to be real money – look back at the airline bailout enacted two weeks after 9/11 (P.L. 107-42) – that was T&I jurisdiction and it only said that “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the President shall…Compensate air carriers in an aggregate amount equal to $5,000,000,000…” – words like “shall” or “are made available” do the trick and create budget authority.)

Having authorizing committees create their own budget authority to fund new programs does fly against the spirit, and occasionally the letter, of the 1974 Budget Act. But the Budget Act was a product of its time, and times have changed.

Congressional process vs. statutory process. The Congressional budget process was established in 1974 and revolves around Congress enacting an annual budget blueprint which gives the Appropriations Committees their annual one-year spending total for their bills and which gives all other committees multi-year spending totals under which all of their spending bills and laws must fit. The blueprint also set total targeted spending, tax and deficit levels for the whole government. The process is enforced internally within Congress by points of order, which can be waived by a House majority vote and in the Senate by either a simple majority or a 60-vote supermajority.

Between 1985 and 1990, a separate statutory budget process was created. This process wrote into law annual caps on total discretionary appropriations and created a “PAYGO” process where each year’s laws changing mandatory spending and revenues were supposed to even out to avoid deficit increases. These enforcement mechanisms were backed by across-the-board “sequestration” spending cuts that would take place whether or not Congress took internal votes to waive points of order – only a change in law could stop enforcement of the budget rules, so the President gained veto power. Importantly, these rules were enforced whether or not Congress adopted an annual budget blueprint, and the statutory processes wound up supplanting the internal Congressional processes. Predictably, Congress stopped passing annual budget blueprints, failing to do so in fiscal 1999, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2019 and 2020.

To the extent that the restrictions on creation of new “backdoor” spending by the 1974 law establishing the Congressional budget process were about deficits and fiscal probity, those concerns are addressed today by the pay-as-you-go law – and PAYGO is agnostic as to whether money is taken from a trust fund or from general revenues, so long as the total outcome is estimated to be deficit-neutral over five-year and ten-year periods. Likewise, the 1974 Congressional backdoor spending rules required all bills providing new contract authority to have that contract authority drawn on a trust fund that was at least 90 percent dependent on taxes that were related to the purpose of the spending (like the Highway Trust Fund was at the time). But there is no requirement under PAYGO for the taxes or other pay-fors to have any relation to the purpose of the spending.

If an infrastructure bill reported from the T&I Committee were to include new mandatory general fund budget authority, like the language shown above, it would have to be subject to PAYGO.

PAYGO advantage #1. Using PAYGO to correlate tax increases with spending has two key advantages over using a trust fund to do so. That advantage involves the answer to this question: what happens if the projected revenues from your tax increase are significantly lower than anticipated?

Assume you enact a law that creates $10 billion per year in new spending, drawn from a trust fund, and you levy new taxes that are projected to bring in $10 billion per year, to be deposited in that trust fund. But then, a couple of years later, the actual tax receipts are several billion per year below the original projections.

In that case, you have the situation we have seen happen over and over with the Highway Trust Fund since 2008 – you either have to cut back your planned spending, raise more taxes, or bail out the trust fund from outside (or some combination of the three).

But suppose instead that you enact a law that creates $50 billion in new general fund mandatory budget authority, and offsets that $50 billion through the PAYGO process with a new tax or taxes estimated to bring in $50 billion over ten years. What happens if the actual tax receipts fall significantly short of $50 billion?

Nothing happens – at least, nothing happens to that $50 billion in spending. That’s because PAYGO is based entirely on spending and revenue estimates made at the time a bill is being enacted into law. If actual tax receipts fail to live up to the estimates, that’s somebody else’s problem. It doesn’t affect your $50 billion in spending at all. (The federal deficit will be higher than predicted, and Treasury will have to borrow more money than expected, but the specific spending that was originally offset with the revenues that never materialized will be unaffected.)

Here’s a real-world example. In 1979, Congress was trying to fulfill President Carter’s promise to deregulate oil supplies and thus end shortages. To make sure that oil companies didn’t make out like complete bandits, Congress was considering what was called an “oil windfall profits tax” (actually a tax on the cost of a deregulated barrel of oil compared to a inflation-adjusted baseline cost under regulation).

The new tax was estimated to bring in $393 billion over ten years. House Public Works and Transportation chairman Jim Howard (D-NJ) had been trying to find a dedicated revenue source for mass transit funding, and he offered an amendment to dedicate one-fourth of the oil windfall profits tax revenue to a New Public Transportation Trust Fund. This would have allowed Howard to double transit spending, from around $4 billion per year to at least $8 billion per year in short order.

Congress did not agree to Howard’s plan, and the enacted oil windfall profit tax was entirely deposited in the general fund. That was a good thing, because the estimators who predicted the tax would bring in almost $400 billion over a decade did not anticipate that the price of a barrel of oil would drop by 80 percent, in real dollars, from 1981 to 1986, which had a corresponding effect on windfall profits tax receipts (which had been projected to be $41 billion in 1986 but were really only $9 billion). Congress repealed the windfall profits tax in 1987. Over ten years, instead of bringing in $393 billion, it only brought in $80 billion. (See the full story here.)

Had Congress dedicated one-fourth of windfall profits tax receipts to a transit trust fund, the trust fund would have required a bailout by 1983 or so, and Democrats in Congress would have been in the position of having to ask Ronald Reagan himself to save mass transit by raising taxes somewhere else. Not a good position to be in.

The Congressional, OMB and Treasury estimators are actually pretty good at forecasting future tax receipts (the windfall profits tax fiasco was an outlier). But they are much better at forecasting changes to existing taxes than they are at predicting the receipts of new taxes. The more novel the revenue source, the less accurate the estimate of its annual receipts is likely to be.

PAYGO advantage #2. The other advantage of PAYGO is that its gaze only reaches ten years into the future. If the new subject-to-PAYGO spending provided by a bill takes longer than ten years to fully “spend out,” then it’s as if the outlays occurring after year ten don’t exist. PAYGO rules only require offsets for the outlays that occur in the first ten years.

For capital-intensive infrastructure programs, which spend out very very lowly, this can be important.

(There is a separate Senate-only point of order against bills that increase the federal deficit by more than $5 billion in a decade after the ten-year budget window, but that point of order can be nullified or waived in the next budget resolution, if 50 Senators and House Democratic leaders agree.)

However, there is a separate Senate-only provision that would prevent post-window deficit increases from a budget reconciliation bill. Which is yet another reason that reconciliation is not the best way to deal with infrastructure spending.

The most important thing. There are a variety of methods that Congress can use to fund surface transportation, but simply bailing out the Trust Fund once again is probably the worst one, since another bailout like the last one, coupled with the significant spending increases that the current situation seems to demand, would through outlays and tax receipts so far out of balance that bringing the Trust Fund back to solvency five or six years hence would be well-nigh impossible. A balanced (perpetually solvent) Trust Fund, at whatever maximum user tax level Congress is comfortable with, could be supplemented by guaranteed, multi-year general fund spending, and the resulting hybrid process could be one way for Congress to support significantly increased infrastructure spending in a responsible way.

The views expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Eno Center for Transportation.