November 9, 2017

As part of the 2015 FAST Act, the FASTLANE Discretionary Grant Program, launched in 2016 under President Obama and now called INFRA, allows the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) to distribute funds to highway and freight projects across the country. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently examined how DOT made funding decisions and created recommendations for the current Administration’s execution of future INFRA grants.

The GAO released the results of its examination in a report to Congressional Committees. Very similar to Eno’s Life in the FASTLANE report from February, the GAO recommended that DOT increase transparency of its processes by developing an evaluation plan that defined how staff would assess and apply criteria and assign ratings to project. They recommended that DOT staff lay out this plan prior to soliciting proposals for future rounds of grants. Once DOT awards the funding, GAO recommends that DOT fully inform all applicants of how their projects ranked and rated. Finally, GAO recommends that DOT fully documents the processes selection processes, making future GAO reports much easier to conduct.

GAO noted that the DOT never implemented similar recommendations that it and other organizations like Eno made on similar grant programs, such as the TIGER discretionary grant program.

The GAO report also contained valuable insights about how the FASTLANE process functioned, highlighting some areas for further improvement.

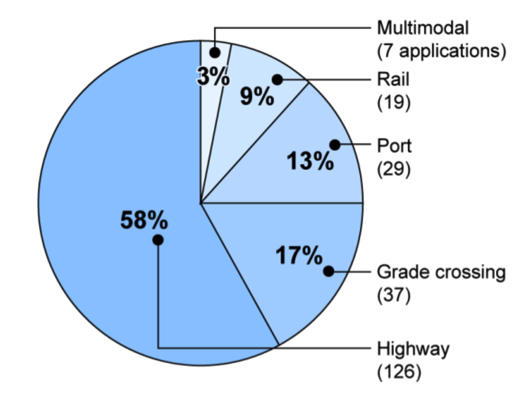

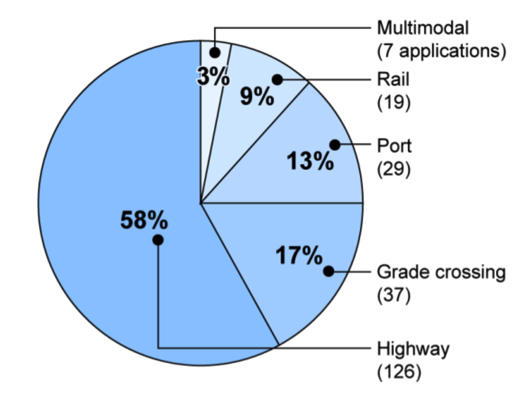

The GAO analysis unsurprisingly found a large appetite among applicants for funding, but the applicants were submitted an outsized proportion of freight projects. About 10 percent of the total program’s five year funding is reserved for intermodal freight projects, yet 42 percent of the total 2016 applicants were for freight. DOT received 218 applications, of which only six were determined to be ineligible. While 58 percent of the applications were for small projects, those represented a small fraction of the total requested dollars (specific details on the program’s statutory requirements can be found on Eno’s 2017 report).

Source: GAO Report 18-38

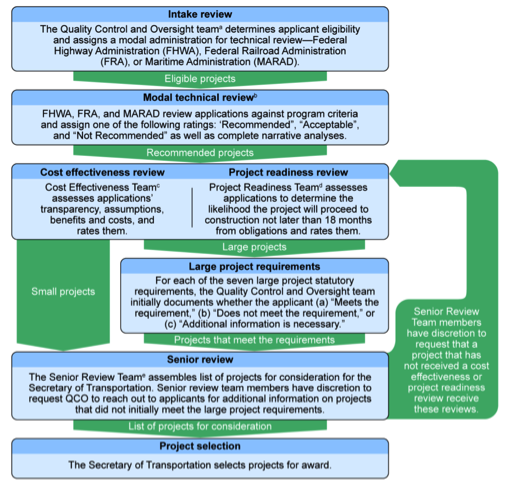

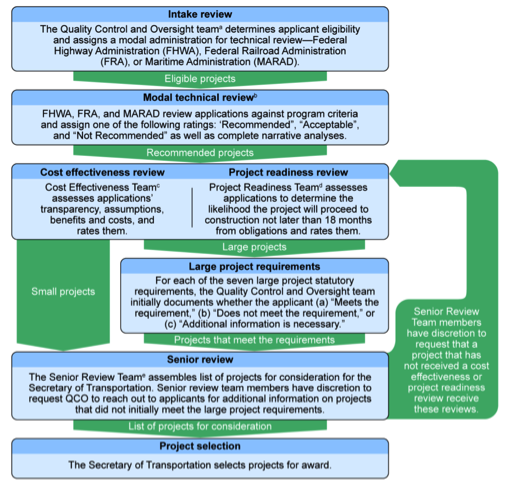

The GAO report details the selection process, outlined in the graphic below. Through this process, most projects were approved: in the modal technical review phase, which is the first hurdle projects face, the teams gave 69 percent of projects a “recommended” rating and 25 percent an “acceptable” rating. Only 12 of the 218 applications were deemed “not recommended.”

Not only were most projects approved, the technical review teams developed their own, independent processes and used inconsistent rating systems. For example, FRA “recommended” a project if it met at least one of the six stated criteria, but MARAD “recommended” a project only if it met three or more of the six. The FHWA team changed their process midway through the review: originally they “recommended” a project only if it specifically mentioned freight aspects, but later removed this requirement. The lack of internal coordination among modal review teams resulted in fewer maritime projects: MARAD “recommended” only 41 percent of their projects, while FRA and FHWA recommended 68 and 77 percent, respectively.

Source: GAO Report 18-38

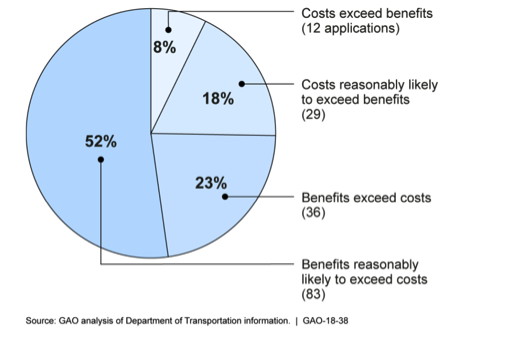

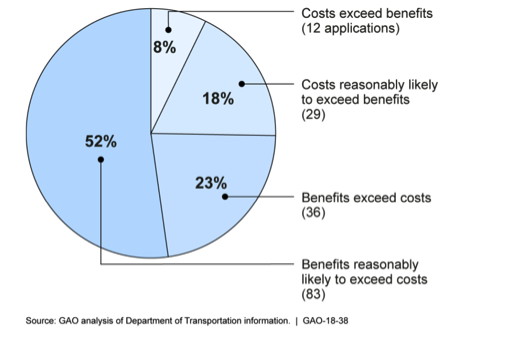

Many of the recommended projects had questionable cost benefit ratios. DOT could determine that benefits would certainly exceed costs for only 23 percent of projects, yet they recommended 60 percent to the Secretary for selection.

Source: GAO Report 18-38

The senior review team inconsistently advanced projects to the selection phase based on requesting additional information and, in some cases, modifying the proposals based on that information. DOT documentation stated that several projects with high ratings in all three technical categories were note advanced to the final phase because additional information was necessary but the senior review team took no action. For example”

One such project … had ratings of “recommended,” “benefits exceed costs,” and “low risk,” but received no follow up to obtain additional information regarding one of the statutory requirements [and thus was rejected]. On the other hand, for one awarded project, DOT obtained additional information regarding two statutory requirements and, later, modified the project proposal by removing a specific component so it could meet another two of the statutory requirements [thus advancing the project].

The resulting process did not provide sound analysis on which projects should receive awards – it only removed some projects from the mix. The senior review team eventually handed the Secretary a list of 130 projects (88 small and 42 large) for selection, and under the guidelines the Secretary had full discretion in making the final selection. Of these 130, only 18 were selected. DOT said that this large of projects was necessary to meet the “statutory requirements,” but did not indicate which. In fact, the senior review team was reluctant to disqualify applicants in part because they were directed to provide the most options to senior leadership.

DOT has already released its NOFO for the 2017 round of INFRA, which modifies the assessment approach. And while DOT agreed with the GAO recommendations, the NOFO does not address transparency as it relates to how projects would be assessed under the new recommendations. A federal discretionary grant program is a vital part of a federal freight and highway program. Consistency and fairness are essential to retaining support for such a program and preserving it beyond the expiration of FAST.