(Clicking on hyperlinks in the text will take you to original source documents, many of which are from the Eisenhower Library or other National Archives facilities and have never before been available online.)

Now that the Clay Committee had issued its report, the immediate question was how much of the report should be endorsed by the President, and the precise form that draft legislation embodying the President’s recommendations should take. An original plan to submit a message and legislation to Congress by January 27 was delayed. As detailed in the memos written by John S. Bragdon, a series of meetings took place in the White House in January and February to incorporate Commerce, Treasury, and Budget Bureau input into the highway message and bill.

In particular, Treasury Secretary Humphrey was against the Highway Corporation being entitled to any kind of general draw on the Treasury. At his request, the plan to be submitted by the President was changed – the bonds would be secured by the gasoline and diesel tax, and all receipts from that tax through the year 1987 in excess of $623 million per year would be transferred to the Corporation to repay the bonds.

Eisenhower’s message accompanying the Clay report, submitted on February 22, cited four reasons in favor of a massive road-building program: (1) the death and accident total on unimproved roads; (2) the costs that bad roads are imposing on drivers; (3) the need for quick evacuation of cities in case of atomic attack; and (4) the costs of future congestion if road capacity did not grow in tandem with the economy.

The Senate goes first

By the time the Commission’s report was formally submitted to Congress along with the President’s message, the key feature of the plan – issuing $20.2 billion in bonds and tying up most federal gas and diesel tax revenues until 1987 in order to pay back the bonds and their interest costs – were already under fire on Capitol Hill. In particular, Senate Finance Committee chairman Harry F. Byrd, Jr. (I-VA) was extremely critical of the debt service costs and other elements of the plan in a statement he made on January 18 – before the plan had even been submitted to Congress.

In the Senate, the chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads, Albert Gore, Sr. (D-TN), had already introduced his own plan as S. 1048 (84th Congress) on February 11 and had begun holding hearings on the legislation. The day after the Clay Commission’s report was submitted and legislation implementing the plan was introduced (by request) as S. 1160 (84th Congress), several Senators at one of Gore’s hearings complained of being unfamiliar with the contents of the Senate bill. One scholar later wrote that “These comments cast further light on what was evidently the complete failure of the administration to consult, in a genuine manner, with influential members of the Senate on the program which it expected them to espouse.”[1]

The hearings were extensive, and by the end, it had become clear that the Clay bill had become a partisan football. The Democratic National Committee released a “fact sheet” in opposition to the bill on April 20, criticizing the bill for borrowing too much, doing so in an off-budget way that might be constitutional, and placing an “undue emphasis on the interstate system to the detriment of other parts of the highway system.”[2]

After the hearings, Gore called for a subcommittee vote on his bill, which the subcommittee approved 6 to 3. Then, the full Public Works Committee rejected the Clay Commission’s approach by a 9 to 4 vote and then approved an amended version of the Gore bill, 8 to 5.[3] Gore’s bill, as approved by the panel, did not allow bonding, did not create an independent corporation to oversee the program, and only provided five years worth of contract authority for the Interstate program (totaling $7.75 billion). However, the Gore bill did increase spending for the regular federal-aid program from $700 million per year to $900 million per year.

It should be noted that the Gore bill did not include any assumption of any tax increase, in large part because the Senate lacks no power to originate tax measures (and the Public Works Committee within the Senate has no power to draft them, even if they are not intended to pass the constitutional test to become law). Moreover, it bears repeating that prior to passage of the 1956 law there was no formal connection whatsoever between fuel tax revenues and highway spending levels, and all highway spending was drawn from the general fund of the Treasury. So, while there was a widespread belief that the higher spending levels under the Gore bill might someday require higher tax rates, there were no visible taxes in the bill.

The tension on taxes was made obvious in the minority views filed in the Public Works committee report by the three senior Republican members of the panel, “Not only do the majority fail to directly tackle our greatest needs, but they blindly refuse to be concerned with the fact that the people of this country have been taxed, and taxes, and taxed, and that the public debt has mounted to staggering proportions. They ignore the administration’s solution of building the Interstate System without any increase in taxes and on a sound debt-liquidating basis (pay-as-you-use). They refuse to take into account the fact that roads are a capital asset which generate their own revenues.”[4]

It is important to note that the minority views condemned increases in the “public debt” at the same time they proposed paying for the Interstate System by issuing debt. This seeming contradiction was made possible by the Clay Committee’s too-clever attempt to declare debt generated for a federal purpose as non-federal debt. The Clay plan would create a Federal Highway Corporation with the authority to issue up to $21 billion in debt. Section 105 of the bill specified that “the obligations, together with the interest thereon, are not guaranteed by the United States and do not constitute a debt of or obligation of the United States.”[5] The debt of the Corporation was thus not technically part of the “public debt” and would not be subject to the statutory debt ceiling.

However, the Corporation would be performing a governmental function and would receive automatic appropriations of all federal gasoline and special fuel taxes in excess of $622.5 million per year under the terms of the Clay plan. So even though the debt of the Corporation would not technically be part of the federal books, it would have the same nod-and-wink status that now pertains to Tennessee Valley Authority debt and which until 2008 pertained to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac debt – Wall Street was essentially told that while the bonds weren’t technically guaranteed by the federal government, if things went wrong, a federal bailout would surely come. And in case Wall Street did not get the message, the Clay proposal would have allowed the Social Security Trust Fund and other federal trust fund accounts to invest in the Corporation’s bonds.

These sophistries were not enough to mollify the most influential Senator on tax and debt issues, Finance chairman Byrd, who took to the Senate floor during debate on S. 1048 on May 25, 1955, exceedingly prepared. (By this point in the debate, Public Works ranking Republican member Edward Martin (R-PA) had offered a substitute amendment to the Gore bill consisting of the Clay Commission proposal.)

Harry Byrd did not like debt. A biographer wrote that “He had an almost pathological abhorrence for borrowing that went beyond reason to the realm of deep emotion.”[6] Byrd first told the Senate that “The interest, estimated by the Clay Committee at 3 percent would be $11.5 billion. In other words interest would cost an amount equal to 55 percent of the bond issue…As an advocate of more and better roads, I am opposed to spending 55 percent of the cost for interest which will never build a foot of road – good or bad.”[7]

But Byrd’s biggest ire was saved for the Clay plan’s intention to tie up 32 years worth of gas tax receipts to pay for the first ten years worth of spending: “All of the funds would be expended in the first 10 years, and in the next 22 years no funds would be available from the Federal gasoline tax. All the receipts from this tax for that 22-year period would be required for repayment of bonds with interest. In other words, the gasoline tax would be dried up for 22 years – from 1966 to 1987 inclusive.

“It is obvious, of course, that the need for road construction and improvement will be just as essential during that 22-year period as it is now…In fact, no Congress can obligate a subsequent Congress to a dedication of taxes.”[8] (Byrd then cited the opinion of the Senate Legislative Counsel that future Congresses would be free to use gasoline tax receipts for other purposes.) Byrd had also received an opinion from the Comptroller General of the United States summing up the nature of the bonds to be issued by the Corporation: “We feel that the proposed method of financing is objectionable because the result would be that the borrowings would not be included in the public debt obligations of the United States…While the obligations would specifically provide that they are not guaranteed by the Government, it is highly improbable that the Congress would allow such obligations to go into default when one considers that the credit standing of the Federal Government would be involved.”[9]

Byrd summed up by saying, “…it is by the devious methods I have mentioned that this debt would be created, and its advocates claim it would not be a Federal debt. We must remember that we cannot avoid financial responsibility by legerdemain, nor can we evade debt by definition. If, by some hollow words in a bill passed by Congress, we could declare public debt not to be the Government’s solemn promise to repay what it has borrowed, we could by the same process wipe out the $280 billion of Federal obligations we owe to citizens, trust funds, banks, insurance companies, and so forth.”[10]

Towards the end of the debate, Sen. Prescott Bush (R-CT) (father of George H.W. Bush and grandfather of George W. Bush), the ranking member on the Roads Subcommittee, was swayed by Byrd’s words and offered an amendment to the Clay Commission substitute clarifying that the Corporation’s bonds had federal backing and would be subject to the statutory federal debt ceiling, but pressure from supporters of the President’s plan made Bush withdraw his amendment. The Senate then defeated the substitute amendment containing the Clay Commission plan by a vote of 31 yeas, 60 nays.

Shortly thereafter, the Senate passed the Gore bill (S. 1048), as amended on the floor, by voice vote. But by limiting funding authorizations to five years and entirely avoiding the question of whether and how to raise taxes to pay for the additional Interstate spending, the Gore bill was an easy vote. The House would have a harder time.

The House kills the bill

In the House of Representatives, the chairman of the Roads Subcommittee was George Fallon (D-MD). In winter and spring 1955, Fallon held a long series of hearings on various versions of the Clay Commission bill. On February 24, the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee (and former House Parliamentarian) Clarence Cannon (D-MO) went to the House floor and moved that the legislation implementing the Clay Commission bill be removed from Public Works Committee jurisdiction and re-referred to the Appropriations Committee. Cannon lost on a non-record vote of 87 yeas, 131 nays, and when Cannon asked for a recorded vote, he could not get the constitutionally required one-fifth of the members present in the chamber to agree to a recorded vote, so the jurisdiction over the future of the highway program stayed with Public Works.

Fallon’s hearings were thorough: “In some areas, the House hearing was much more searching than on the Senate side. Moreover, it appeared obvious from the outset that the House committee was determined to embark eventually on a course of its own with respect to this matter, that is, to write its own bill.”[11] Fallon introduced his own bill (H.R. 7072, 84th Congress) without Republican support on June 28. On the spending side, the Fallon bill was very similar to what wound up being enacted in 1956 — $24 billion in contract authority over 12 years for Interstate construction, and an immediate boost in spending for the regular federal-aid program to $725 million per year in 1957. But the remarkable thing about the Fallon bill was that it contained significant tax increases ($24 billion over 12 years) on gasoline, diesel fuel, and truck tires – and that the Speaker then referred the bill to the Public Works Committee, not the Ways and Means Committee.

This part bears emphasis – before 1975, House rules did not permit committees to share jurisdiction over a bill. Upon introduction, the Speaker referred a bill to one committee only, no matter how many other committees’ jurisdiction the bill touched, and that committee had sole power over whether the bill lived or died. Due to the primacy of the Ways and Means panel in the House, it was traditional that even an off-hand reference to the Internal Revenue Code would cause the Speaker to refer a bill to Ways and Means, despite the vast preponderance of the bill’s subject matter dealing with non-tax issues. For the Speaker to refer a bill containing significant taxes to Public Works, rather than to Ways and Means, was very unusual.

The original Fallon will would have increased the gasoline tax by 50 percent (from two cents per gallon to three cents) but its other tax increases would have fallen disproportionately on truckers – a tripling of the diesel fuel tax (from two cents per gallon to six) and a new tax on truck tires and inner tubes that the truckers said would be equivalent to a tenfold increase in the existing tax.

A contemporaneous account says that “From the day of introduction of H.R. 7072, there occurred one of the most intense pressure campaigns observed on Capitol Hill for many years. The trucking, oil, rubber, and certain allied interests, it appeared, worked unceasingly to arouse sentiment against the tax provisions…It has been estimated that more telegrams and letters were received by members of Congress during this period than at any time since the dismissal of General MacArthur, which was supposed to have set a record.”[12]

While Fallon and Public Works were the experts on highway policy, and they probably had a good handle on which highway interests should be taxed in order to pay for the Interstate system, they were newcomers to tax politics, or in how to work with outside interests when raising their taxes, and it showed. At a July 6 executive session, the Public Works panel could not agree on a bill, so they delegated a nine-member ad hoc subcommittee (also headed by Fallon) to deliberate further, and the ad hoc group revised the tire taxes somewhat. It was then decided to hold further hearings on the bill, and five members of Ways and Means were delegated to sit with Public Works during the hearings, which quickly grew too large to be held in the Ways and Means hearing room, and which then had to be moved to what is now the Cannon Caucus Room, during which all manner of industries complained mightily about the taxes in the bill.[13]

The Public Works markup of H.R. 7072 lasted almost six full days and resulted in a “clean bill” (H.R. 7474, 84th Congress) incorporating all amendments adopted to that point being introduced on July 19 and reported without amendment on July 20. The reported bill cut the increase in the diesel tax in half, further restructured the new taxes on tires and tubes, and added an excise tax on truck, trailer and bus sales.

On the way to the House floor, the Rules Committee granted a special rule (H. Res. 314, 84th Congress) which prevented members from offering any amendments on the floor to the tax portion of the bill (a reflection of the “closed rule” process which had characterized House consideration of Ways and Means tax bills since World War II). But the rule did allow Republicans to offer the Clay Commission bill as a substitute. The rule passed by a vote of 274-129-1, despite some objections during debate on the rule (including one by Rules Chairman Howard Smith (D-VA), who said “Here we are in the last 5 days of the session being asked to deal with this tremendous proposition. What are you thinking about? This should not be considered at this time and none of these bills ought to be passed.”)[14]

During the debate on the bill, the rule allowed Public Works ranking minority member George Dondero (R-MI) to offer an amendment on the floor substituting the Clay Commission’s plan for the Fallon plan, and the amendment failed on a non-recorded teller vote of 178 to 184 on July 26. However, the House amended the Dondero amendment on the floor to add Davis-Bacon prevailing wage applicability for Interstate projects (which the Fallon bill already had), meaning that the first vote was not on a “clean” version. At the end of debate on July 27, another member offered the original text of the Clay Commission proposal as a motion to recommit the bill with amendatory instructions. That motion lost by a recorded vote of 193 to 221, setting the stage for the final passage of H.R. 7474.

However, a funny thing happened on the way to the House-Senate conference committee – the House overwhelmingly defeated the Fallon bill on final passage. The vote was 123 yeas to 292 yeas, meaning that more than two-thirds of the House voted against the bill.

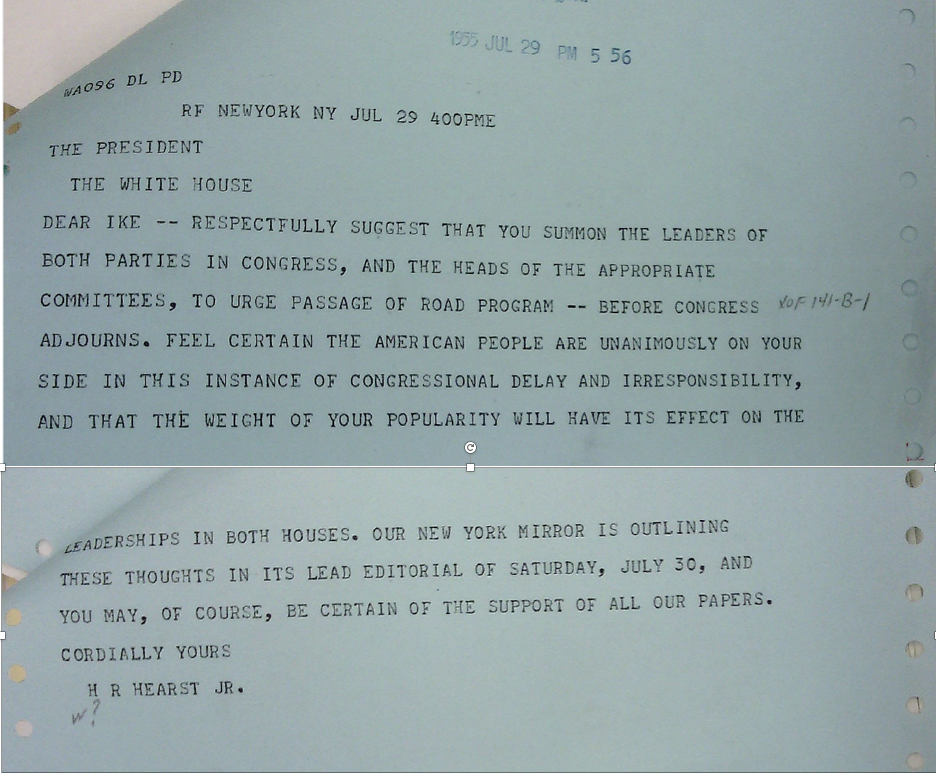

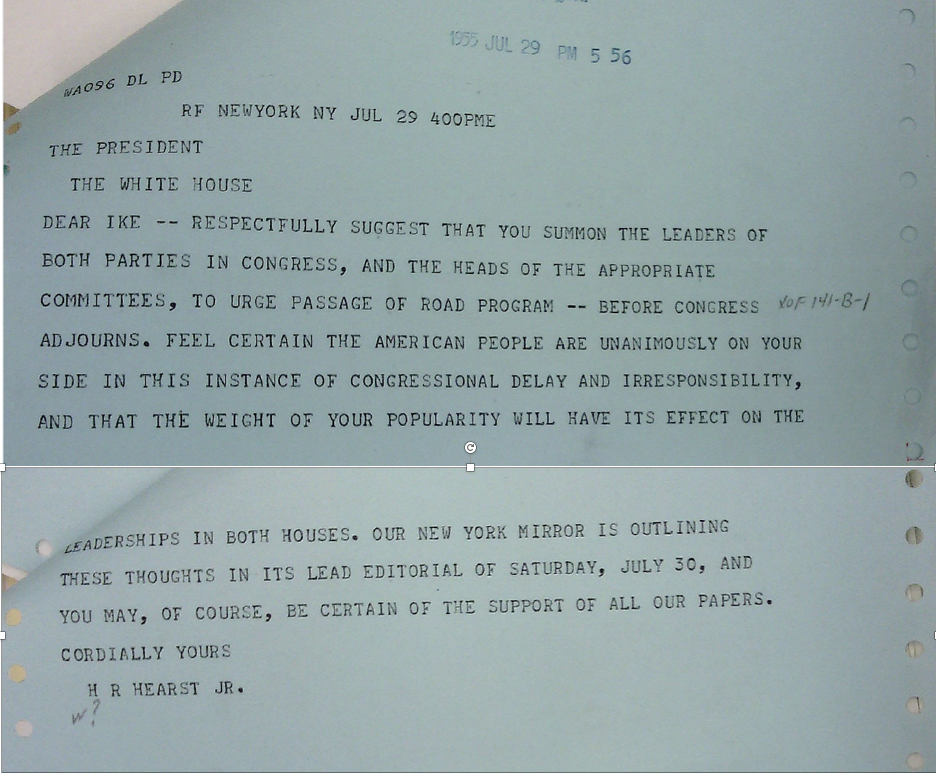

Telegram sent from William Randolph Hearst Jr. to President Eisenhower just after the House voted down the highway bill in July 1955.

Eisenhower issued a statement that he was “deeply disappointed” with the House’s action, that disagreements over how to finance the program should not stop work on the legislation, and that he “would devoutly hope that the Congress would reconsider this entire matter before terminating this session.”[15] But no further action was taken, and the first session of the 84th Congress adjourned sine die on August 2, 1955.

Some of Eisenhower’s advisers proposed to recall the Congress into a special session solely for consideration of the highway proposal, but Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs “There was no sense in spending money to call them back when I knew advance that the result would be zero.”[16]

Blame for the collapse of the bill was widespread. The head of the American Association of State Highway Officials told his membership that “…the bill was the biggest public works program ever proposed, and early in the session it took on a political flavor, and it was also so big that special interests became involved, and it was no longer the consideration of a conventional Federal-aid road bill. When certain interests in the Congress insisted on a pay-as-you-go feature, additional taxes were required, and you might sum it up by saying that the Democrats defeated the Republicans’ bond bill, and the special interests defeated the increased taxation proposed by the Democrats.”[17] A contemporary scholar quoted the House Majority Whip as saying that the truckers were “the ones who killed the bill” and quoted the House Majority Leader as saying that “I have a sneaky idea that the truckers of this country played an important part in what happened.”[18]

Washington journalist Theodore H. White quoted the head of the American Trucking Association as saying after the vote, “Yes, we had considerable influence in killing the Fallon bill. But don’t confuse the Fallon bill with the highway program. We’re not such stupid idiots as to be opposed to a road program we need as much as anyone else. We were about the first group to support the highway program from the beginning. We supported it before both Senate and House, we agreed to accept increased taxes to pay for it – we’ll pay our fair share, the same tax rate on fuel, tires and equipment everyone else pays.”[19]

A historian at the Federal Highway Administration quotes a statement made by Frank Turner, the legendary former FHWA Administrator who had earlier worked with Fallon as a kind of detailee to help draft his 1955 bill, in an oral history 32 years later as attributing the failure to the internal committee politics of the House: “It was very, very obvious what was happening. You have to know that at the time, the Ways and Means Committee not only was the committee on finances and taxes for the House, but it was also the committee on committees. And no member of the Congress could get on any committee in the Congress without being approved by that committee on committees…The Ways and Means Committee, wearing its finance hat, tax hat, was teed off at the Public Works Committee, treading on their turf in taxes. Even though they had had this informal arrangement, they didn’t like it, period. And they passed the word that they didn’t like it and they didn’t want the bill passed because of this jurisdictional question…all 435 members of Congress realized, recognizing that they owed their committee assignments to these guys on the Ways and Means Committee, they did what the Ways and Means Committee wanted. And they passed the word, appropriately, that they didn’t want that bill passed, and so it didn’t pass.”[20]

Turner’s retrospective analysis has two problems. First, while the Democratic caucus of the Ways and Means Committee also served as the Democratic Committee on Committees, this was not true for Republicans, who had a separate Committee on Committees making appointments. Second, if the Democratic leaders of the Ways and Means Committee were opposed to the Fallon bill and wanted it defeated, they were extraordinarily stealthy and subtle about it, as twelve of the fifteen Democratic members of the panel voted “yes” on H.R. 7474 on final passage, including the chairman and the next nine voting members in order of seniority.

A better explanation of the relationship between turf politics and the final vote came five months after the vote from a rank-and-file member of the Roads Subcommittee, Clifford Davis (D-TN), who said that “I felt that a better job could have been done on any increase in tax provisions to pay as we go, and pay as we use, if the Committee on the House Ways and Means had been given the responsibility which rightly belonged to that committee. They have career staff experts on duty the year around. They have the benefit of the advice of the Department of the Treasury…Not being an experienced member of the tax-writing committee, and with only 12 hours to be informed on the tax provisions, I was not willing to vote for a bill so important…”[21]

In their book Interstate, Mark Rose and Raymond Mohl summed it up by saying, “But finally, legislative ineptitude killed the Clay plan…Beginning in February, reports that Clay’s bill would not survive in Congress – brought in by men with years of experience counting votes – were discounted. Surely, Eisenhower’s aides must have reasoned, with such strong support from state governors, men who were playing politics would succumb to political pressure. Thus Eisenhower, Clay, and Adams, also men with strong convictions about good highway legislation, stuck to their original plan.”[22]

After the adjournment, Congress, the White House, and stakeholders had time to regroup. It was obvious to all that no proposal to finance the Interstate system via the issuance of bonds would pass Congress. Yet it was equally obvious that tax increases on transportation stakeholders were not viable unless some mechanism could be found to reassure the stakeholders that their money would bring them enough tangible and direct benefits to make the tax increases worth their while.

Having rejected calling Congress back for a special session in 1955, Eisenhower and his top aides instead reached a tentative decision to form another Cabinet committee to rework their proposal for the start of the next session of Congress in January 1956.

After signing a number of bills, pocket veto messages, and other items on August 12 (including John S. Bragdon’s appointment as Special Assistant to the President for Public Works Planning), he left Washington, heading for his “Summer White House” in Denver, Colorado, expecting not to return to Washington until early October.

He was gone longer than that. On September 24, Eisenhower was admitted to a Denver hospital after suffering a heart attack. He would remain in that hospital until discharged on November 11, and thereafter was on light duty at his farm in Pennsylvania or at Camp David until returning to Washington for full duty on December 11.

While Eisenhower was gone, however, the rest of the government continued to function.

The Yellow Book gets specific with urban routes

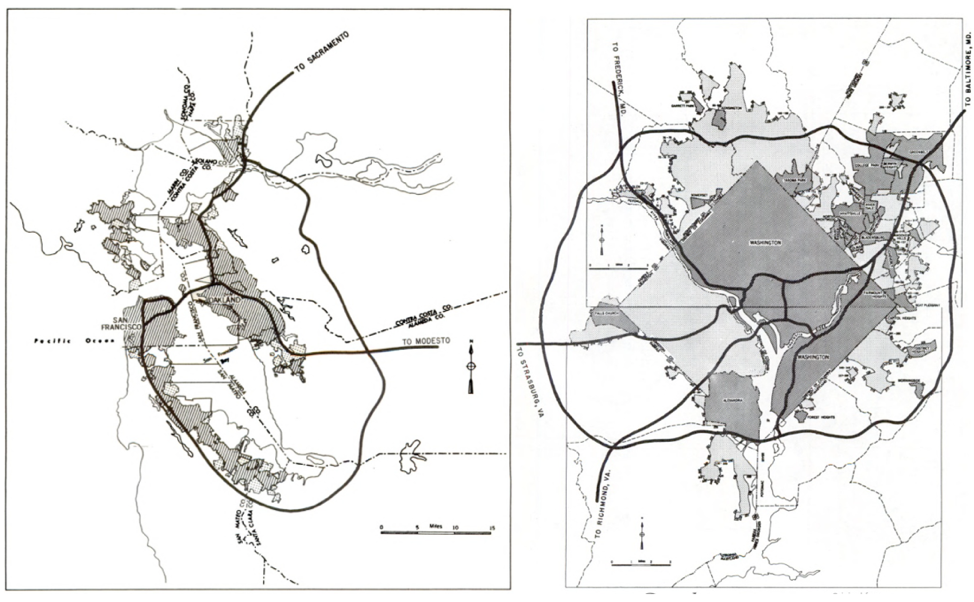

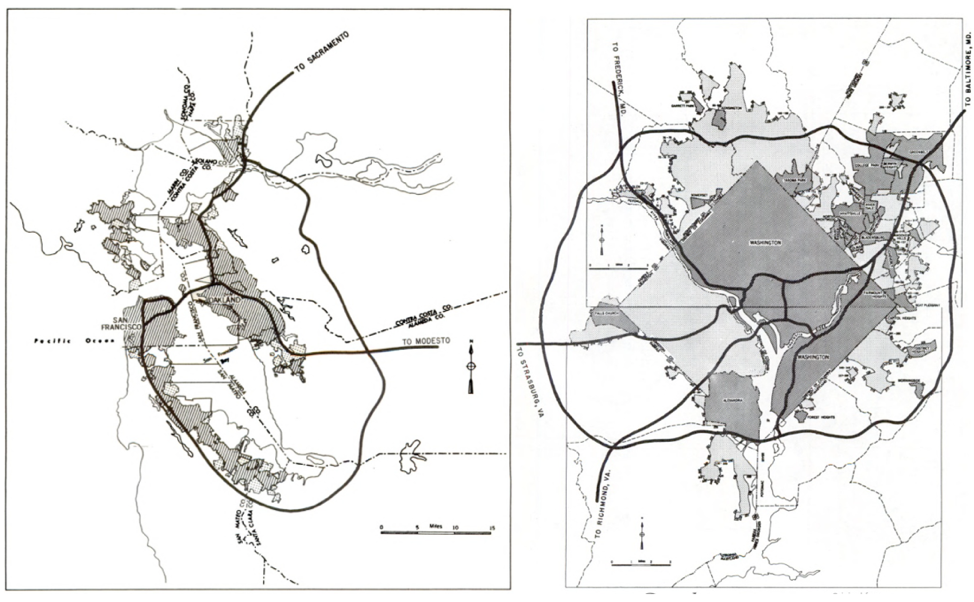

The fact that the Interstate system would go through urban areas was never a secret – it just wasn’t well-advertised until fall 1955. The original 1947 map contained 37,681 of the authorized 40,000 miles of Interstate, and the annual report of the Public Roads Administration for 1947 said at the time that that total included “2,882 miles of urban throughfares. Urban circumferential and distributing routes are to be designated later, and 2,319 miles have been reserved for these routes.”[23] The anticipated routes through cities, however, were too small to be seen on the national map, and the map was usually the only document relating to the Interstate route plan that was being widely circulated in the mid-1950s.

Until fall 1955. It had also been public all along that the missing 2,319 miles from the 40,000 mile authorized system were going to be given to additional circumferential and distributing routes (aka bypasses, beltways, and spurs) in urban areas, and the Commissioner of Public Roads explained to a Senate subcommittee in April 1955 the criteria by which those additional urban routes were being selected.

Public Roads made the route selection of the final 2,319 miles official on September 15, 1955, and afterwards, the projected routes for most cities were published in a widely distributed document called “General Location of National System of Interstate Highways Including All Additional Routes in Urban Areas Designated in September 1955” and known as the “Yellow Book” because of the bright color of its cover.

Maps of proposed Interstate extensions around and through San Francisco (left) and Washington DC (right) from the 1955 Yellow Book.

The maps in the Yellow Book made it extremely clear where the 5,201 miles of urban Interstate were to go, and urban members of Congress would be armed with that specific information when the next version of legislation funding Interstate construction came before the House. Urban mileage would constitute 13 percent of the planned 40,000-mile system.

The Cabinet functions without Ike

The Cabinet held an unscheduled meeting on September 30, six days after the President’s heart attack, in part to show continuity of government. At that meeting, presided over by Vice President Nixon, chief of staff Sherman Adams told the Cabinet that state governors had appointed their own highway committee, to meet on November 3, and that the Cabinet should form its own committee to come up with a plan to give the governors. Adams said that Lucius Clay had fallen ill and was unable to resume his duties. A Cabinet Committee was formed (Commerce-Treasury-Agriculture-Defense, with a White House staff member), to report back to the Cabinet in time to take a Cabinet decision to the governors on November 3.[24]

The Cabinet Committee reached an initial consensus and was ready to report back to the Cabinet at their October 28, 1955 meeting. The centerpiece of the Clay Committee proposal – financing the system by the issuance of bonds – was gone, with the Treasury Secretary admitting it was a mistake to have proposed it in the first place. They kept the Clay plan for spending $26 billion on the designated 40,000 miles of Interstates, but this time, it was to be financed by “a 2¢ increase on gasoline, an increase on tires, a tax on camel back [rubber], and an increase of 2% on the excise tax on trucks and buses, bringing it up equal to the automobile excise. Sherman Adams “asked and was assured that the tax increases would be devoted completely to the roads program,” which implicitly involved some kind of formal mechanism to segregate those tax receipts from the rest of the budget. At the end of the meeting, the Cabinet approved the presentation of the plan to the governors on November 3.[25]

The meeting with the governors was held on schedule, and their reaction “was not good,” according to a Treasury official who was at the meeting. His notes on the meeting indicate that Commerce Secretary Weeks told the governors that “we had about come to current financing (with some borrowing) because the Clay program was not acceptable to Congress, and no one seemed to want the Federal government to use toll roads.” Treasury refused to contemplate diverting existing general revenue taxes to roads (as it would increase the federal deficit), and after the meeting, the Treasury aide felt that “A 2-cent gas tax increase would apparently be strongly opposed. One-cent may be acceptable if coupled with higher truck taxes.”[26]

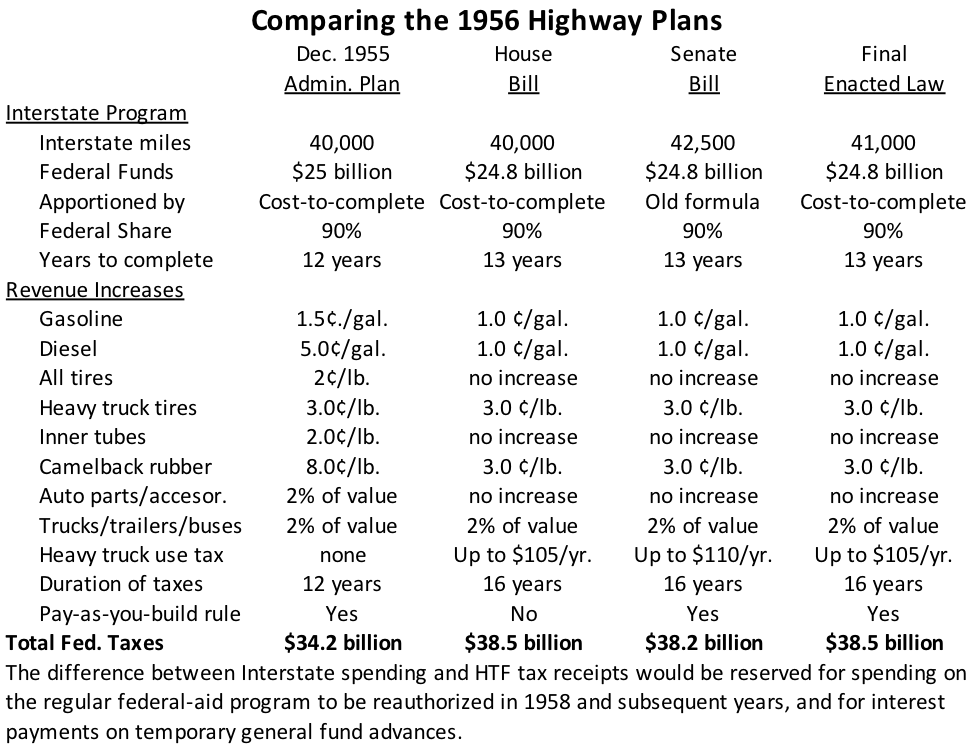

Despite the skepticism from the governors, a revised plan was ready to take to the President and Cabinet by December 8. The plan itself was a simple one-page document with nine bullet points, among them the scope of the plan (40,000 miles of Interstate costing $25 billion at a 90-10 match to be completed in 12 years; $9.8 billion in other federal aid over that period), the revenues raised (tax increases of 1.5 cents on gasoline, 5 cents on diesel fuel, up to 5 cents per pound on tires, and a 2 percent sales tax on trucks, buses, trailers and auto parts), the absence of reimbursement to states for their own toll roads, all on a “pay-as-constructed” basis.

The last bullet point indicated that an “early special presidential message [to Congress] accompanied by proposed legislation” was in process.[27] However, Eisenhower briefed Republican Congressional leaders on the plan in a December 12 meeting, and during that meeting (according to the minutes), “several warnings were voiced on the efforts of the opposition to pin on the Republicans the responsibility for increased taxes. Sen. Knowland suggested the President merely cite the need for roads and call for a bill with ‘adequate financing provisions.’ The consensus was that the question of financing should not be raised in the State of the Union message; instead, that exploratory discussions should be undertaken with Democratic leaders.”[28]

Eisenhower took the leaders’ advice. There was no 1956 special message to Congress, no bill sent up to Capitol Hill, and no specific endorsement of a tax increase at the start of the session. While the January 1956 State of the Union message said that construction of “the whole Interstate System must be authorized as one project, to be completed approximately within the specified time, where funding was concerned, he only said that any solution must stay within the “bounds of sound fiscal management” and that “there must be an adequate plan of financing.”[29] And the President’s 1957 budget request, transmitted to Congress on January 16, 1956, called for a balanced federal budget for a second consecutive year, but where highways were concerned, the budget only had dollar amounts for “the continuation of the present annual authorization. The new highway program should be soundly financed so as not to create budget deficits.”[30]

Discussions with Congressional leaders were continuing. On January 10, Rep. Charlie Halleck (R-IN) told the President that Speaker Rayburn was “still adamant against the corporation plan of financing” while Eisenhower weighed in against any public debt increase.[31] And at a January 31 meeting with Republican leaders, the minutes say “It was agreed that in order to increase the chance of success of this program the Administration should yield to Democratic insistence on financing through new or additional taxes and should cooperate in the development of an appropriate tax proposal to finance construction without any resort to deficit financing or dependence on existing revenues.”[32]

The Administration works with Congress

In the 1956 session, the Speaker would not again let the Public Works Committee write the tax portions of the bill – the two committees would work separately. The Public Works subcommittee chairman introduced a bill (H.R. 8836, 84th Congress) authorizing the spending on January 26, providing $24.8 billion in funding for Interstate construction over thirteen years (fiscal 1957 through 1969), to be apportioned to states on the basis of their share to complete construction of the entire system. The Commerce Secretary testified at a February 7 Public Works hearing on the bill, somewhat critical of the 13-year timeframe instead of the Administration’s ten years, but also got drawn into a long argument with Public Works chairman Charles Buckley (D-NY) about a provision in the bill to reimburse states like New York for the construction cost of roads, toll and otherwise, that they had already completed which would be incorporated into the Interstate.[33]

On the revenue side, Rep. Hale Boggs (D-LA), the eighth-ranking Democrat on the Ways and Means Committee, took leadership on the issue by introducing a bill he had been working on for months. (His press statement on introduction of the bill said that “It is understood that the President, after a conference with the Honorable Joseph W. Martin, Jr. (Repub., Mass.), House Republican leader, has decided to abandon his plan for issuing bonds as a means of financing the highway program, and that the President now approves and supports the proposed pay-as-you-go method of financing, to which Mr. Martin has pledged bipartisan support.”[34])

The Boggs bill (H.R. 9075, 84th Congress) shifted the burden of the increased taxes so that it did not fall so heavily on the trucking industry – the taxes on heavy truck tires, in particular, were drastically reduced, and the increased tax on diesel fuel was reduced to the same level as the increased tax on gasoline. However, the taxes under the original Boggs bill would simply be deposited into the general fund of the Treasury, not segregated in any way.

In order to meet the intent of the Cabinet as expressed in the October 28, 1955 meeting that receipts from new highway taxes not be fungible with the rest of the budget, the Treasury staff had come up with an idea. A draft legislative provision dated February 8, 1956 called for the creation of “The Interstate Highway System Fund” to be “classified for budget purposes as a trust fund” into which highway user taxes would be deposited and from which Interstate highway funding would be spent.[35]

Then, the Secretary of the Treasury, George Humphrey, told a February 14 Ways and Means hearing that the proceeds from the new taxes should be handled “the same way as we handle the trust funds…There is a provision for the estimating of amounts and the crediting of accounts. And I would handle these the same way we do trust funds.”[36]

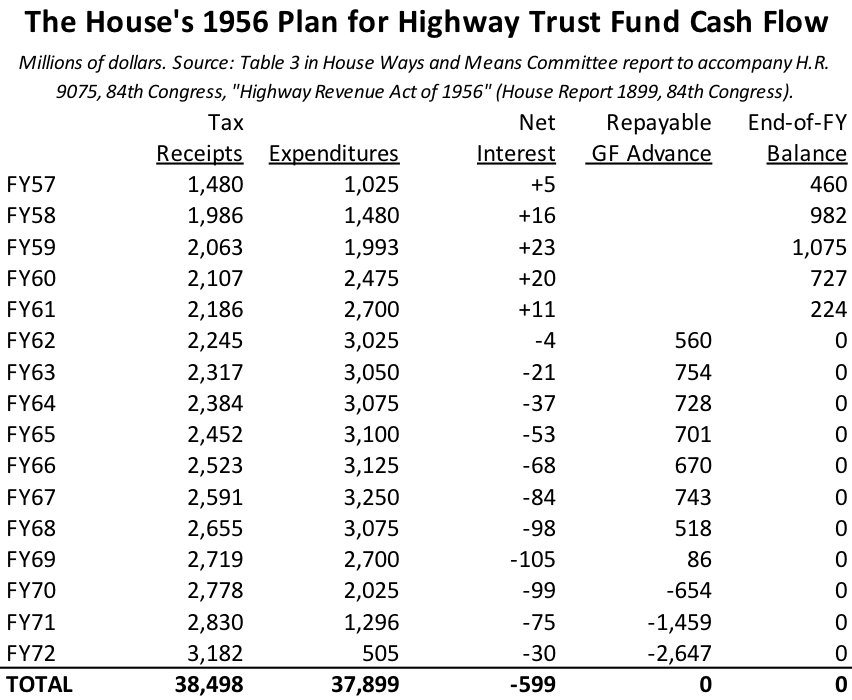

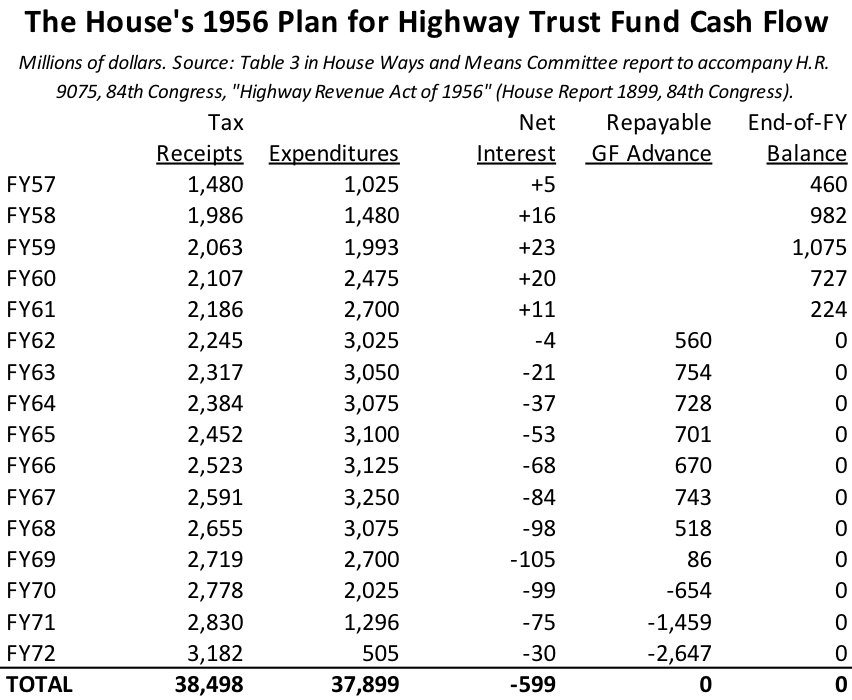

By the time Ways and Means reported the bill unanimously on March 19, 1956, the panel had added an amendment depositing all federal gasoline, diesel, and tread rubber taxes and the increased share of taxes on tires and on truck and trailer sales into a new Highway Trust Fund. The committee report made clear that “…the trust fund is expected to be self-sustaining over the 16-year period. In any case, however, your committee provides in the section on the highway trust fund that it is the declared policy of Congress to bring about a balance of total receipts and total expenditures of the trust fund for the entire period involved and it is stated that if it hereafter appears that this balance will not be obtained, Congress is to enact legislation in order to bring about such a balance.”[37]

The Republican members of the committee, in supplemental views filed with the report, claimed credit for the new trust fund structure: “We recommended, and the committee accepted, the establishment of a highway trust fund. The existence of this fund will insure that receipts from the taxes levied of finance this program will not be diverted to other purposes. Moreover, it will make it easier for the Congress as well as the public to determine to what extend the costs are being met on a pay-as-we-build basis. The highway program should be financed without resort to budgetary deficits.”[38]

However, just because the trust fund was to be self-sustaining “over the 16-year period” under the Ways and Means bill did not mean that deficits could not build up in the interim. As the table below shows, the Ways and Means plan would have resulted in the trust fund borrowing large sums from the general fund, at interest, from 1962-1971 before eventually paying off the completed Interstate system. The net cost of interest paid to the general fund over the life of the trust fund was estimated to be about $600 million, a far cry from the $11.5 billion to be paid to private investors under the Clay Commission plan.

It took the Public Works Committee a little bit longer to rework the funding formulas for the spending half of the legislation in order to garner more votes, but the two bills were eventually combined into one bill (H.R. 10660, 84th Congress), and reported to the House on April 23. The next day, Eisenhower met with the Republican Congressional leadership, where there was still discontent over issues in the House bill like Davis-Bacon labor standards, toll road reimbursement, and the plan in the House bill for year-to-year borrowing from the general fund by the Trust Fund. A consensus was reached that the Senate, not the House, was the place to fix those problems.[39] The following day, at his weekly press conference, Eisenhower was asked about the Boggs bill and claimed ignorance of the details but simply said “we need highways badly, very badly, and I am in favor of any forward, constructive step in this field.”[40]

The bill came before the House for debate on April 26, 1956. Boggs told the chamber that “For a great many years now, highway users have complained, and I think with some justification since the conclusion of World War II and the Korean conflict, that vast revenues were being collected from them but were not being used for purposes of building highways. This bill recognizes that complaint and it establishes the highway trust fund which dedicates most of these funds to highway construction and for that purpose only…I discovered that virtually every highway user group – from the American Automobile Association to the various trucking organizations – has for years recommended that the Federal excise taxes levied upon highway users be dedicated and set aside for the purpose of financing the improvement and extension of the Federal highway system. This recommendation is premised upon the intense feeling of highway groups that it is only fair to utilize the Federal excise taxes on gasoline, diesel fuel, lubricating oil, passenger automobiles, trucks, buses and trailers, automobile parts and accessories, and tires and tubes, for the purpose of constructing roads.”[41]

During amendment debate the following day, no amendments were offered relating to the Trust Fund, and the bill passed by the near-unanimous margin of 388 to 19 – no mean feat, since a bill spending the exact same amount of money and raising roughly the same amount in new taxes had garnered 265 fewer “yes” votes the previous year. What changed from 1955 to 1956? A redistribution of the tax burden so it did not hit truckers quite so hard, some changes in the apportionment formulas benefitting urban areas, and the establishment of a new Highway Trust Fund to segregate the new taxes from the rest of the budget and ensure their dedication to the purposes of the underlying legislation without fear of diversion.

In the Senate, the House bill first went to Public Works, which kept the same basic overall spending level (with year-by-year variations) but increased the overall Interstate system mileage from 40,000 to 42,500, meaning that the Administration (or a subsequent Administration) would be able to award 2,500 more miles of routes to be built at a 90 percent federal cost share. Public Works reported the bill on May 10, at which point it went to the Finance Committee.

Treasury Secretary Humphrey had been in touch with Finance chairman Byrd on this subject for some time – he had sent Byrd a “Dear Harry” letter marked “Personal” on March 23 complaining about several features of the House bill, including the fact that “there would be some very substantial deficits running to about three-quarters of a billion dollars a year during the middle years of the program. This would make a bad drain on the general budget during this period. A motion to put the program on a real pay-as-you-build basis by keeping expenditures in line with receipts was defeated in the House Ways and Means Committee. I especially hope you will be able to do something about this part of the bill.”[42]

Humphrey made a similar suggestion in the May Finance Committee hearings, asking “I urge that the bill be amended to permit allocation of funds to be so timed that the estimated expenditures will not exceed the estimated available amounts in the trust funds. With this change, the program could be kept from being a charge on the regular budget.”[43]

When marking up the bill the following week, Byrd made the change Humphrey had requested – he added an amendment to the tax title of the bill requiring that Interstate apportionments to states be reduced on a pro rata basis any time the Secretary of the Treasury determined that the Highway Trust Fund would otherwise be forced to reach a cash deficit at the end of the upcoming fiscal year. Then, if tax receipts improved, the withheld contract authority could be restored to states in subsequent years as the Trust Fund was able to support the extra outlays.

Floor debate on the Senate amendments to H.R. 10660 was almost entirely devoted to the issues of Davis-Bacon applicability and limitations on truck sizes and weights, and the taxes and the trust fund were scarcely mentioned. On May 29, 1956, the Senate passed the bill by voice vote.

As the House and Senate prepared to go to conference on the bill, the minutes of the June 5 White House meeting with Republican leaders indicated that the Administration had five top priorities: (1) keeping Interstate mileage at 40,000 unless additional funds were provided, (2) avoiding rigid funding apportionment formulas, (3) no reimbursements to states for toll roads, (4) maintaining the pay-as-you-build Byrd Test, and (5) weakening or killing Davis-Bacon applicability.[44]

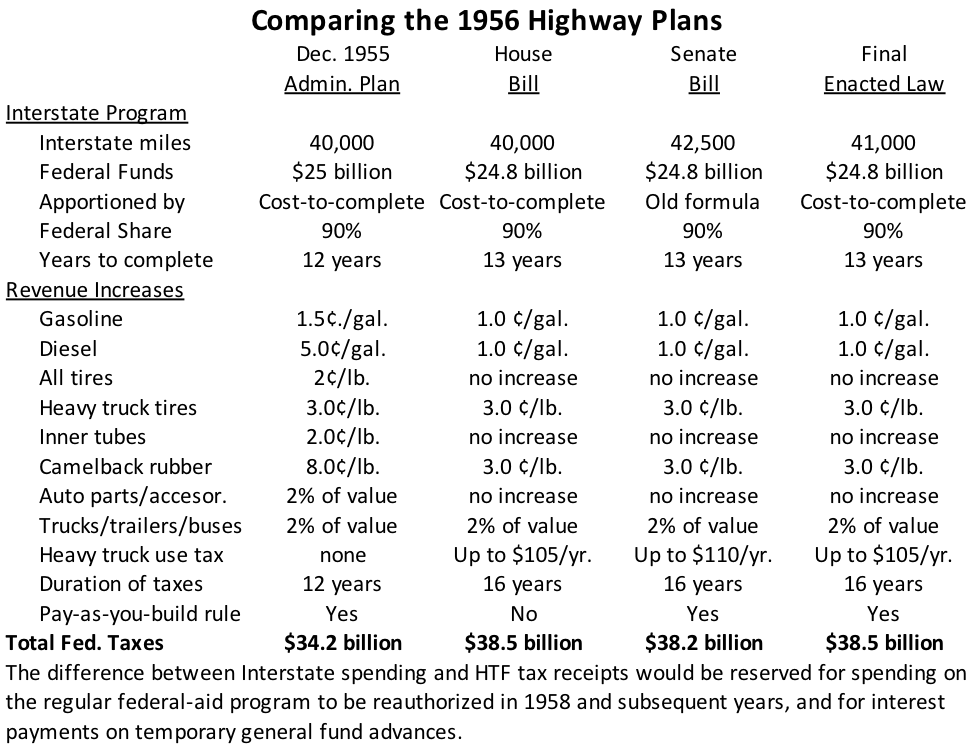

By the time the conference concluded on June 25, the Administration had done fairly well on its top five priorities – the amount of new Interstate mileage was cut from 2,500 to 1,000, the Interstate money after 1958 was to be distributed via a regularly updated “cost to complete” method, there were no toll road reimbursements, and the Byrd Test for annual trust fund solvency stayed in the bill. Davis-Bacon applicability, however, stayed in the bill.

The conference committee made some changes to spending formulas and settled some tax differences around the margins (dealing with non-highway gas use and other exemptions) but kept the House tax levels. When the final conference report was submitted to Congress on June 26, it passed the House by voice vote and passed the Senate by a vote of 89 to 1.

Every federal agency polled urged the President sign the bill (which was a formality, as a veto was never really a question) President Eisenhower signed H.R. 10660 into law (70 Stat. 374) three days later.

There was no formal signing statement, and no ceremony – Eisenhower had been hospitalized at Walter Reed Army Hospital since June 8, recuperating from intestinal surgery. He signed the highway bill into law there, in his hospital room, with only one aide as a witness.

With the stroke of a pen, Eisenhower had created $24.8 billion in federal funding for construction of the Interstate system – an incredible sum, considering that total federal spending for the fiscal year about to end on June 30 was only $70.6 billion. $24.8 billion was equivalent to 5.6 percent of the fiscal 1956 U.S. gross domestic product.

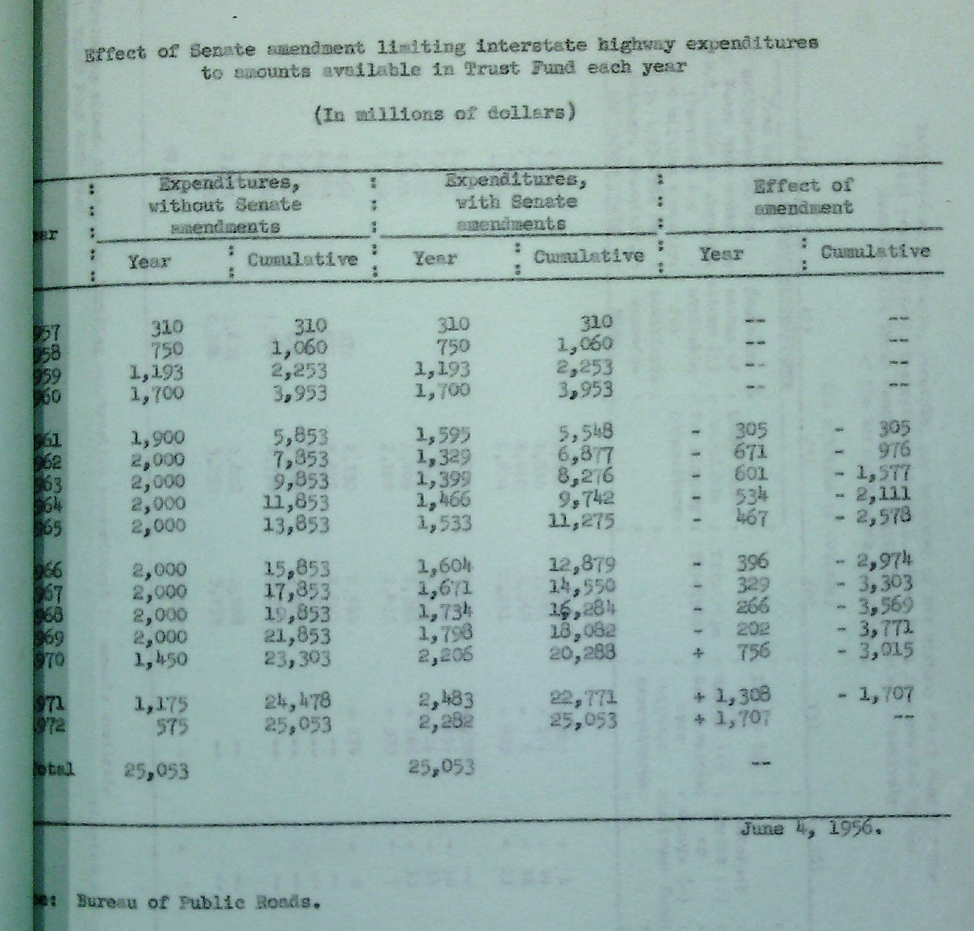

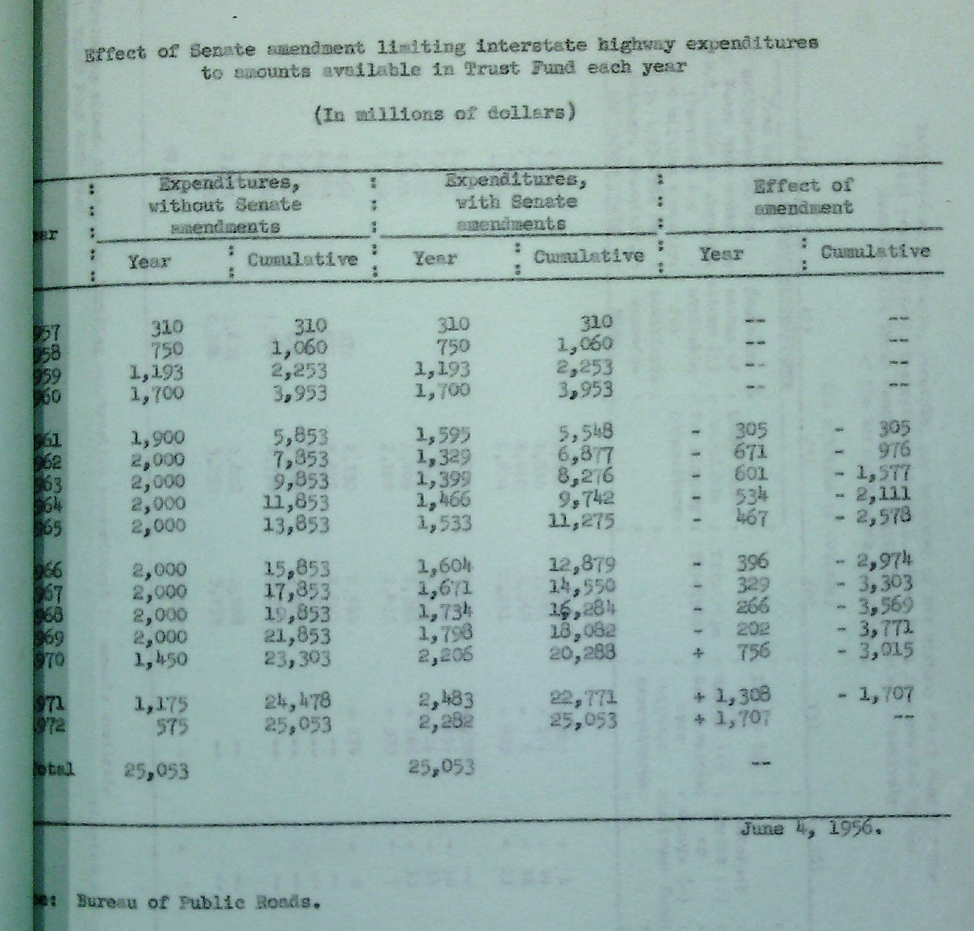

However, the insistence of the Administration (and of Senator Byrd) on including a pay-as-you-build provision in the bill raised questions about how much of that $24.8 billion would be made available on time. Estimates available to the Administration and Congress while the final bill was being negotiated projected that the pay-as-you-build “Byrd Test” would start postponing the release of some of the spending to states as soon as 1959 (in time to stop fiscal 1960 obligations and lower 1961 cash flow). The June 4, 1956 projections estimated that $3.8 billion of funding scheduled to be given out in the 1960s would be postponed to the 1970s, slowing the completion of the system.

The June 1956 “Byrd Test” projections from the Bureau of Public Roads. Original located in Treasury Department Office of Tax Policy records, National Archives.

Continued in Federal Highway Policy Under President Eisenhower, 1957-1961

[1] John M. Martin, Jr. “Proposed Federal Highway Legislation in 1955: A Case Study in the Legislative Process.” The Georgetown Law Journal. Vol. 44 (1956); pp. 234-235.

[2] Democratic National Committee Research Division, “Analysis of the Eisenhower Highway Program” (Fact Sheet RD-55-11, 4/20/55). Original located in the “Reedy: Roads-Highways” folder in Box 415, Office Files of George E. Reedy Series, Senate Papers of Lyndon B. Johnson, 1948-1961 collection, Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, Texas.

[3] Martin p. 240.

[4] Senate Report 350, 85th Congress, 1st Session, p. 34.

[5] Section 105 of S. 1160, 84th Congress.

[6] Alden Hatch. The Byrds of Virginia: An American Dynasty. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969) p. 347.

[7] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 25, 1955, pp. 6995-6997.

[8] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 25, 1955, p. 6996.

[9] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 25, 1955, p. 7000.

[10] Congressional Record (bound edition), May 25, 1955, p. 6997 (1955).

[11] Martin p. 249.

[12] Martin p. 252.

[13] Martin p. 253.

[14] Congressional Record (bound edition), July 26, 1955 p. 11528.

[15] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Statement by the President on Congressional Action Regarding a Nationwide System of Highways, July 28, 1955. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1955 as document 178 on p. 746.

[16] Dwight D. Eisenhower. The White House Years: Mandate for Change,: 1953-1956. New York: Doubleday, 1963. P. 502.

[17] Quoted in Richard H. Weingroff, Kill the Bill: Why the U.S. House of Representatives Rejected the Interstate System in 1955. Federal Highway Administration monograph. Retrieved at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/killbill.cfm on August 18, 2009.

[18] Martin p. 262.

[19] Theodore H. White. “Where Are These New Roads?” Collier’s, vol. 137, no. 1 (January 6, 1956) p. 50.

[20] Weingroff.

[21] Quoted in Weingroff.

[22] Rose and Mohl pp. 83-84.

[23] U.S. Public Roads Administration. “Work of the Public Roads Administration 1947” p. 7. Contained in Eighth Annual Report, Federal Works Agency, 1947.

[24] Minutes of Cabinet Meeting – September 30, 1955. Located the “Cabinet Meeting of September 30, 1955” folder in Box 5 of the Cabinet Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[25] Minutes of Cabinet Meeting – October 28, 1955. Located the “Cabinet Meeting of October 28, 1955” folder in Box 6 of the Cabinet Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[26] Memo from Dan Throop Smith to Treasury Secretary Humphrey, November 4, 1955, subject line “Meeting with Governors on Highway Program – November 3.” From General Records of the Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Policy-Subject Files, Box 7 in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[27] “Department of Commerce – Revised Highway Program.” Original located in the “Legislative Meetings 1955, 5 (December, 1955)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[28] “Legislative Leaders Meeting, December 12, 1955” p. 4. Original located in the “Legislative Meetings 1955, 5 (December, 1955)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[29] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union, January 7, 1956. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1956 as document 2 beginning on p. 1 (quote from p. 18)

[30] Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1957, p. M15.

[31] Memorandum from L.A. Minnich, Jr. to Director Hughes, January 10, 1956. Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1956 (1) (January-February)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[32] “Personal and confidential” memo to Budget Director Hughes, January 31, 1956. Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1956 (1) (January-February)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[33] U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Public Works. National Highway Program – Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. Hearings before the Subcommittee on Roads on H.R. 8836. 84th Congress, 2nd session.

[34] U.S. Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Ways and Means. Highway Revenue Act of 1956 (Hearings on H.R. 9075). Washington: GPO, 1956 p. 13.

[35] “Draft – The Interstate Highway System Fund” and draft explanation, February 8, 1956. From General Records of the Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Policy-Subject Files, Box 7 in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[36] U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Ways and Means. Highway Revenue Act of 1956 (Hearings on H.R. 9075, 84th Congress, 2nd Session) p. 36.

[37] House Report No. 1899, 84th Congress, 2nd Session, p. 9.

[38] Ibid p. 45.

[39] L.A. Minnich, Jr., memo to Mr. Brundage, April 24, 1956. Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1956 (2) (March-April)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

[40] Dwight D. Eisenhower, The President’s News Conference of April 25, 1956. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1956 as document 88 on p. 428 (quote is from p. 431).

[41] Congressional Record (bound edition), April 26, 1956 pp. 6410-6111.

[42] Letter from George Humphrey to Harry Byrd, March 23, 1956. Carbon copy located in General Records of the Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Policy-Subject Files, Box 7 in the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

[43] U.S. Senate. Committee on Finance. Highway Revenue Act (Hearings on H.R. 10660, 84th Congress, 2nd Session) 1956 p. 71.

[44] Unsigned memorandum to Mr. Brundage, June 5, 1956. Located in the “Legislative Meetings 1956 (3) (May-June)” folder in Box 2 of the Legislative Meetings Series of the Ann Whitman File of the Eisenhower Presidential Papers 1953-1961 in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.