(Clicking on hyperlinks in the text will take you to original source documents, many of which are from the Eisenhower Library or other National Archives facilities and have never before been available online.)

Studying future aviation needs

In contrast to the ways in which highway policy played out under Eisenhower, his major aviation policies wound up being implemented through the exact process the President demanded – study within the Administration, followed by study by outside independent experts, followed by adoption of the recommended policies by the Administration, followed by the enactment of laws by Congress largely in line with the Administration’s proposals.

The jet age dawned under the Eisenhower Administration. Boeing flew its “Dash 80” prototype four-engine jet for the first time in July 1954, and the Air Force ordered 29 of the KC-135 variant as refueling tankers the following month (out of an eventual order of 820). This gave Boeing the guaranteed demand necessary to build assembly lines and start selling the passenger airline variant of the KC-135, which Boeing named the 707. This plane, along with the Douglas DC-8, would transform the airline industry and would require much more sophisticated air traffic control.

Boeing 367-80. Dash 80 was the original prototype for the Boeing 707, America’s first Jetliner. Boeing restored the Dash-80 and it was delivered in August 2003 to the Steven F. Udvar – Hazy Center Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Photographic Services NASM Udvar-Hazy Center Photo By Dane Penland.

At the same time, federal jurisdiction was fragmented. Economic and safety regulations for civil aviation were set by the Civil Aeronautics Board. The Civil Aeronautics Authority, under the Department of Commerce, provided civil air traffic control services, enforced safety regulations, and provided airport development grants. The Air Force, Army, and Navy each operated extensive military aviation systems. An Air Coordinating Committee established by executive order under President Truman[1] tried to keep track of them all, but was beset by infighting. (One participant, future FAA head Pete Quesada, called it “the most unsuccessful, abortive conglomerate of conflicting interest you would possibly imagine.”[2])

Under Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, questions of how the federal government should be organized were under the general purview of the Bureau of the Budget. Upon taking office, Eisenhower changed this, creating a President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization under the chairmanship of Nelson Rockefeller. A key permanent member of the Commission was the President’s brother, Milton Eisenhower.

In January 1955, Nelson Rockefeller wrote to his brother Laurence (the major stockholder in Eastern Airlines and an original investor in McDonnell Aircraft) to complain that “no one has taken a really good look at the Nation’s future air transport problems” and suggesting that an outside group make a confidential study of the problem.[3] Rockefeller’s committee eventually retained William Barclay Harding of Smith Barney (he was also the head of the Aviation Securities Committee of the Investment Bankers Association of America).

Harding recruited other outside aviation experts (including Laurence Rockefeller’s adviser Najeeb Halaby) and performed a preliminary study, which was funded under the auspices of the Budget Bureau. Harding’s group’s final report to the Budget Bureau was released in December 1955 and recommended a much larger official study of long-range aviation facilities needs, “under the direction of an individual of national reputation…in such a way that it is clearly the appointee’s responsibility, backed by Presidential authority, to work through and with existing organizations and avoid duplication of the services which they are able to provide.”[4]

Accordingly, President Eisenhower reached out to retired Major General Ted Curtis, a World War I flying ace who had served under Eisenhower as Chief of Staff of Strategic Air Forces in Europe during WWII. Curtis was appointed as Special Assistant to the President for Aviation Facilities Planning in February 1956.[5] Under Eisenhower’s personal authority, Curtis was able to use the resources of the government and outside engineering consultants to research the future demand for air traffic control and airports that would be needed for the coming expansion of the civil aviation sector.

While Curtis was working, the worst civil aviation disaster in U.S. history to that point took place – a mid-air collision of two passenger airliners over the Grand Canyon, killing all 128 persons on both planes on June 30, 1956. The investigation revealed that better air traffic control would almost certainly have prevented the accident. Accordingly, before his full investigation was finished, Curtis issued an interim report in early April 1957 (in time to have its recommendations considered by the First Session of the 85th Congress).

While Curtis was working, the worst civil aviation disaster in U.S. history to that point took place – a mid-air collision of two passenger airliners over the Grand Canyon, killing all 128 persons on both planes on June 30, 1956. The investigation revealed that better air traffic control would almost certainly have prevented the accident. Accordingly, before his full investigation was finished, Curtis issued an interim report in early April 1957 (in time to have its recommendations considered by the First Session of the 85th Congress).

Curtis’s interim report recommended the immediate creation of an independent and temporary Airways Modernization Board to mediate between the Commerce and Defense Departments and conduct initial research and development of an eventual air traffic control system for the U.S. that would handle both kinds of traffic. The pace at which this recommendation was adopted was extremely rapid – two days after Curtis submitted the report, it was approved by the Cabinet, and the report was transmitted to Congress six days after that.[6]

Bills were immediately introduced in Congress and passed the Senate in June and the House in late July. On August 14, President Eisenhower signed into law the act creating the Airways Modernization Board (71 Stat. 349), which was almost word for word the draft bill recommended by Curtis. Meanwhile, as Congress was considering the bill recommended in Curtis’s interim report, he submitted his final report in May 1957 – a concise 39-page summary document together with much longer technical reports on long-term aviation demand and long-term air traffic control structure and technology.[7]

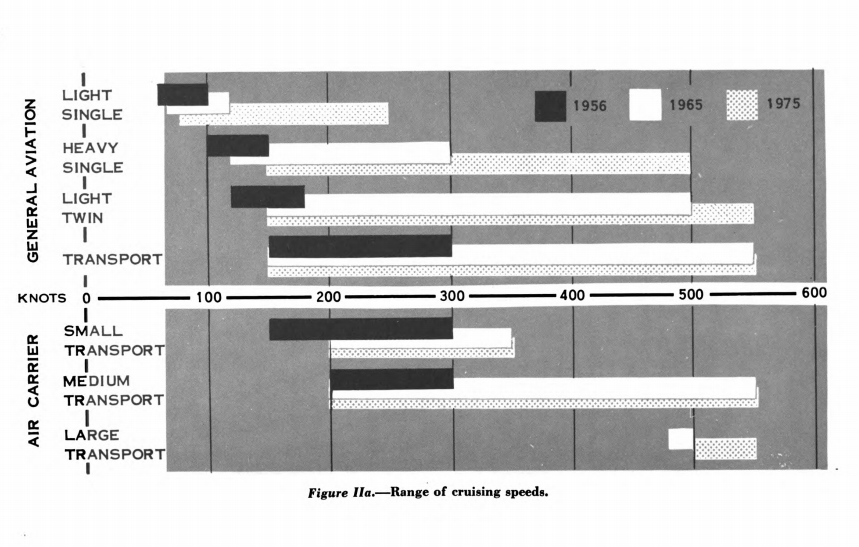

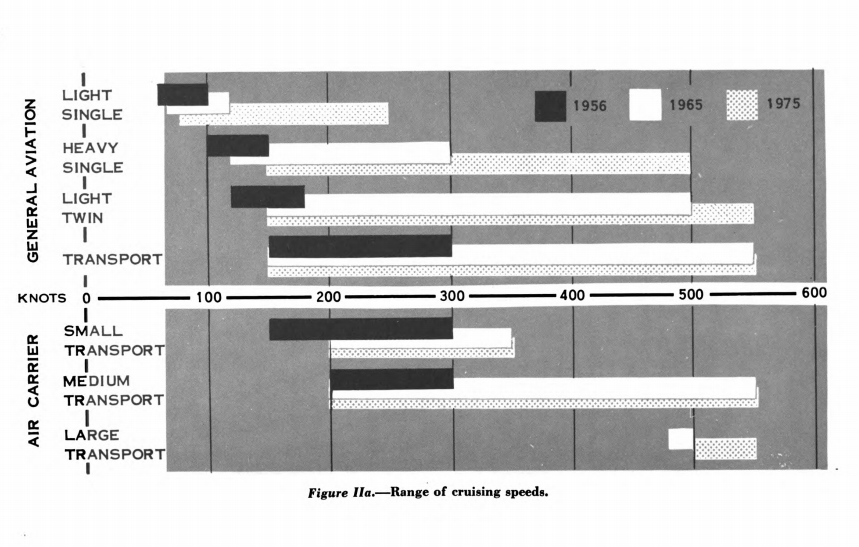

The final report from Curtis predicted massive increases in demand for airspace use by 1975 (an increase from 65 million takeoffs and landings per year in 1956 to 115 million per year in 1975), at much greater altitudes and speeds than at present, but noted that “Except for the addition of radar control around major airports, the air traffic control system now in use is, in its principal technical particulars, much the same system that was devised two decades ago to accommodate the growth in traffic stimulated by the DC-3 – an airplane that cruised at about 160 miles per hour. It was never meant to cope with the complex mixture of civil and military traffic that now fills the air.”[8]

The final Curtis report’s forecast for how greatly jet travel would increase average airspeeds by 1975.

Creating a new agency

Curtis recommended the construction of the modern, radar-based air traffic control system recommended by his technical advisory team – but to run the system, he said “An independent Federal Aviation Agency [FAA] should be established into which are consolidated all of the essential management functions necessary to support the common needs of the military and civil aviation of the United States.”[9] The head of the new FAA would be in charge of U.S. aviation policy, airspace policy, and long-range planning, as well as writing aviation safety regulations and investigating accidents (incorporating functions of the Civil Aeronautics Board), and the FAA would incorporate the Airways Modernization Board (which, by law, would expire in 1960, putting a deadline on the timeframe for FAA creation).

Curtis handed in his resignation immediately upon submitting his final report and was replaced as Special Assistant by retired Lieutenant General Elwood “Pete” Quesada, a pioneer of radar-based aircraft control and coordination during WWII under General Eisenhower. Quesada promptly began work on turning Curtis’ recommendations into workable Administration policy and proposed legislation. (Quesada also chaired the Airways Modernization Board and the Air Coordinating Committee.)

Eisenhower and Quesada hoped to get legislation creating the FAA ready for submission to Congress in January 1959, but events forced their hands. A mid-air collision over Las Vegas between a civilian airliner and an Air Force fighter killed 49 people on April 21, 1958, and another collision over Maryland a month later between another airliner and an Air Force training jet killed 12 people. In both instances, better air traffic separation between military and civilian planes would have prevented the collisions.

On May 21, the day after the Maryland collision, bills creating a new FAA were introduced in both chambers of Congress by the chairmen of the House Commerce Committee and the Senate Aviation Subcommittee.[10] Hearings began almost immediately. The testimony of Quesada and other Administration officials was sought by the Senate panel for June 2 and 3, but the Administration asked for a two-week delay.[11]

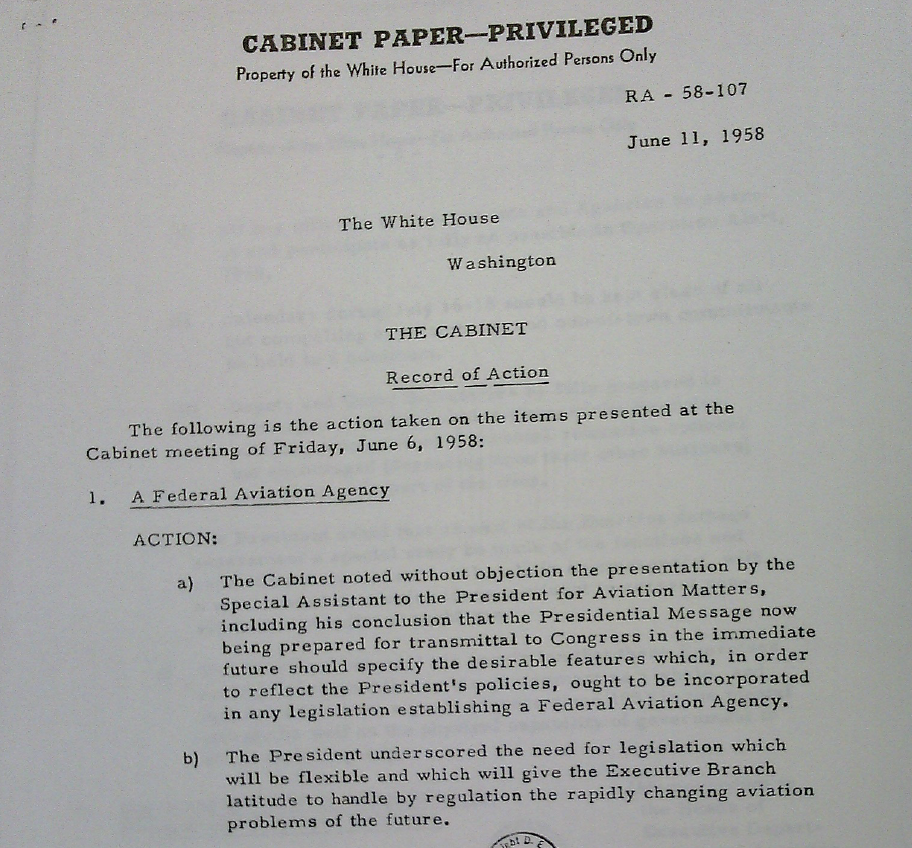

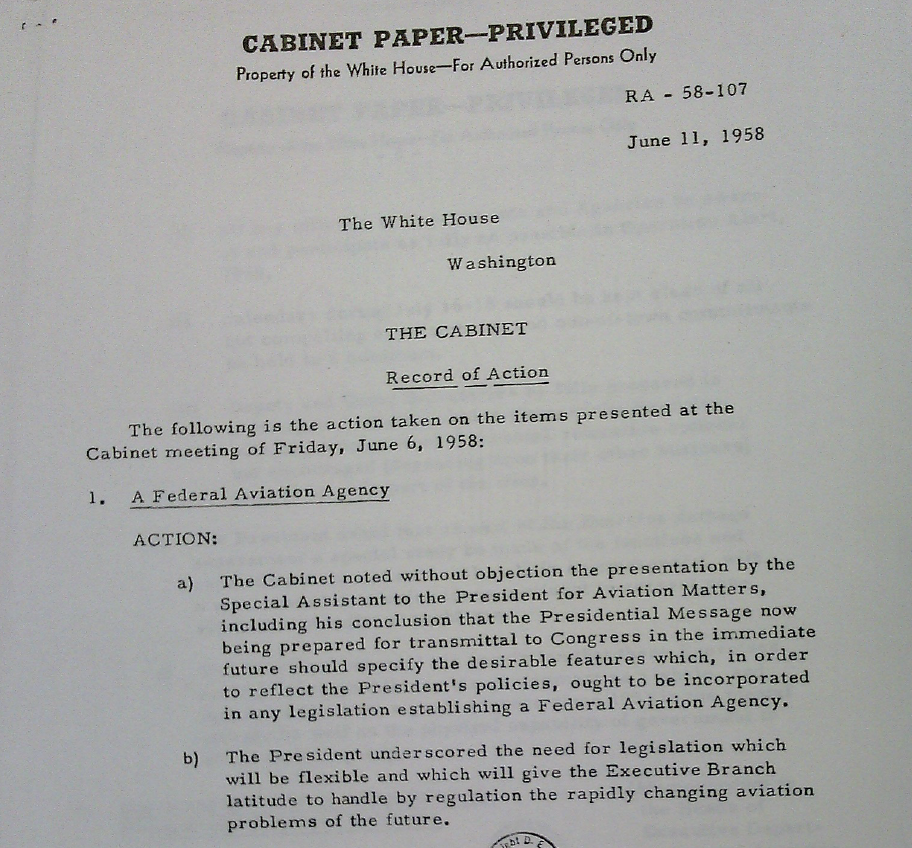

The issue was immediately put on the agenda for the June 6 Cabinet meeting. On June 3, Eisenhower and Quesada met with the Commerce Secretary and the Deputy Defense Secretary to make sure that both departments were on the same page alongside Quesada in turns of ceding jurisdiction to a new agency. At the Cabinet meeting three days later, Quesada briefed the Cabinet on the situation and the bills now in Congress. “With amendments, he believed, this bill could adequately serve the President’s objectives, and he listed some six items that would require change principally to insure that the agency reported to the President rather than to the Congress and that provision would be made for military participation in it.”[12] Commerce Secretary Weeks and Defense Under Secretary Quarles spoke in support of the plan, which was approved by the Cabinet.

President Eisenhower submitted a formal message to Congress on June 13 asking them to pass a bill creating an independent FAA “at the earliest possible date” and giving great detail as to what that legislation should include.[13] Quesada, meanwhile, worked through the Senate bill line by line and came up with a long list of proposed amendments, which he presented to the Senate subcommittee with his testimony on June 16.

The Senate committee marked up its bill on June 24-25 and amended it largely to the White House’s liking. As an indicator of the urgency of the safety situation, the bill passed the Senate by voice vote on July 14, just five days after the committee filed its report. The Senate bill was then reported in the House with a few minor amendments on August 2 and passed that chamber on August 4 (again, by voice vote). A quick House-Senate conference committee was held and reported back a compromise version of the bill on August 11, both chambers agreed to the final changes quickly (once more by voice vote) and President Eisenhower was able to sign the Federal Aviation Agency bill into law (72 Stat. 731) on August 23, 1958.

Due to pressing end-of-session business, there was no formal signing statement for the bill, but Eisenhower promptly gave Quesada a recess appointment to run the new FAA, and the Senate confirmed him to be the FAA’s first Administrator on March 11, 1959.

Who should pay for airways?

The two Curtis reports, the Airways Modernization Act, the Quesada group, and the FAA Act all anticipated significantly increased federal funding for air traffic control to accommodate the jet age. (The idea of taxing aviation system users to pay for some air traffic control costs had been mentioned in two of President Truman’s budgets, but only as a general concept, without any detailed tax proposals.) The final Curtis report contained a substantial discussion of shifting some of the burden of the cost of air traffic control from general revenues to airway users.

The report noted that the user charge concept was more difficult to apply to air traffic control than “than in virtually any other” because airway use was “less tangible, and hence less readily measurable, than the use of surface transportation facilities” and because “the lack of relationship between cost and benefit complicates the problem of equitably pricing the service.” In addition, the fact that the federal government (civil and military) was a direct user of the system, and that there was a flight safety aspect that had general public benefits, also complicated things. Nevertheless, the report urged that the existing 2 cent per gallon aviation gasoline tax (which at that time went to the Highway Trust Fund) and other existing excise taxes “be treated as a user charge” and then be increased (subject to further study).[14]

In January 1958, President Eisenhower’s 1959 Budget stated that “it is increasingly appropriate that [private users of the airspace] pay their fair share of the costs. As first steps toward this end, this budget proposes that a tax of 3½ cents a gallon be levied on jet fuels and that taxes on aviation gasoline be increased to 3½ cents a gallon from the present 2 cents, with increases of ½ cent per year for 4 years in both taxes up to 6½ cents a gallon. The receipts from taxes on aviation gasoline, which now go into the highway trust fund, should be kept in the general revenues to help finance the operations of the airways.”[15]

Congress took no action – the 1958 excise tax extension bill wound up being about elimination of the excise tax on freight transportation to help the railroads. (A separate Senate amendment to repeal the excise tax on passenger transportation, which applied to railroads, buses, and airlines, was dropped in House-Senate conference.)

The following year, Eisenhower’s 1960 Budget included a proposal “ to have users of the Federal airways pay a greater share of costs through increased rates on aviation gasoline and a new tax on jet fuels. These taxes, like the highway gasoline tax, should be 4½ cents per gallon. I believe it fair and sound that such taxes be reflected in the rates of transportation paid by the passengers and shippers.”[16]

Again, Congress took no action – Eisenhower’s legislative proposal on the aviation gasoline tax got tied up in his separate proposal for a highway gasoline tax to keep the Highway Trust Fund from becoming insolvent, and Congress ignored the proposal to take aviation gasoline taxes out of the Trust Fund in order to lower the size of the required increase in the highway gasoline tax.

Finally, in his outgoing 1961 Budget, he repeated, “To help defray the cost of the Federal airways system, the effective excise tax rate on aviation gasoline should be promptly increased from 2 to 4½ cents per gallon and an equivalent excise tax should be imposed on jet fuels, which now are untaxed. The conversion from piston engines to jets is resulting in serious revenue losses to the Government. These losses will increase unless the tax on jet fuels is promptly enacted. The revenues from all taxes on aviation fuels should be credited to general budget receipts, as a partial offset to the budgetary costs of the airways system, and clearly should not be deposited in the highway trust fund.”[17]

That budget estimated that the aviation fuel tax changes would bring in $108 million per year, which was still far short of the $373 million the FAA was estimated to spend on operations that year or the $140 million in estimated capital spending on new air traffic control facilities.

However, as was the practice at the time, Eisenhower’s last budget was delivered to Congress just two days before his presidency ended, and the incoming Administration was not bound to pursue its proposals. President Kennedy did reiterate the proposal to transfer aviation gasoline taxes out of the Highway Trust Fund in his February 1961 highway proposal, saying it was “fair and logical” to take those taxes out of the Trust Fund.[18]

Congress again postponed discussion of aviation taxes until a future day, which would not come until a detailed proposal of the Lyndon Johnson Administration in 1968 was picked up by the Nixon Administration, tweaked, and set to Congress in 1969, to become the Airport and Airway Development Act of 1970, increasing aviation taxes and segregating them in an Airport and Airway Trust Fund to defray most of the costs of air traffic control and airport development.

Airport construction grants

However, the FAA, and its predecessor CAA, didn’t just provide air traffic control and administer safety. They also were in charge of the grants-in-aid program for airport development established in 1946, and on this issue, the Eisenhower Administration and Congress did not always see eye-to-eye.

As originally enacted in 1946, the Federal Airport Act (60 Stat. 170) authorized a total of $500 million in annual appropriations for grants over a seven-year period (later extended). Upon taking office, Commerce Secretary Weeks ordered a complete review of the airport program, and no appropriation was made in fiscal 1954. The review panel’s final report (submitted to Congress in early 1954) recommended that federal aid to airports continue,[19] and Congress provided $22.5 million for them. But Eisenhower’s fiscal 1956 budget proposed cutting airport grant funding in half.

Congress disagreed. The Senate passed a bill that not only provided four years of additional authorization for the airport program (boosted to $63 million per year), but also made that funding available immediately in the form of “contract authority” available outside the appropriations process. (This was the funding mechanism used by the federal-aid highway program since 1923.)

The Bureau of the Budget initially opposed the bill because of institutional opposition to increased use of multi-year “backdoor spending,” but when it was presented to the President in July 1955, the Bureau told the President that “a preference for one method of getting funds to eligible sponsors is not, in light of the bill’s objective, a substantial basis for veto.”[20] The President signed the bill into law (69 Stat. 441) on August 3, 1955.[21]

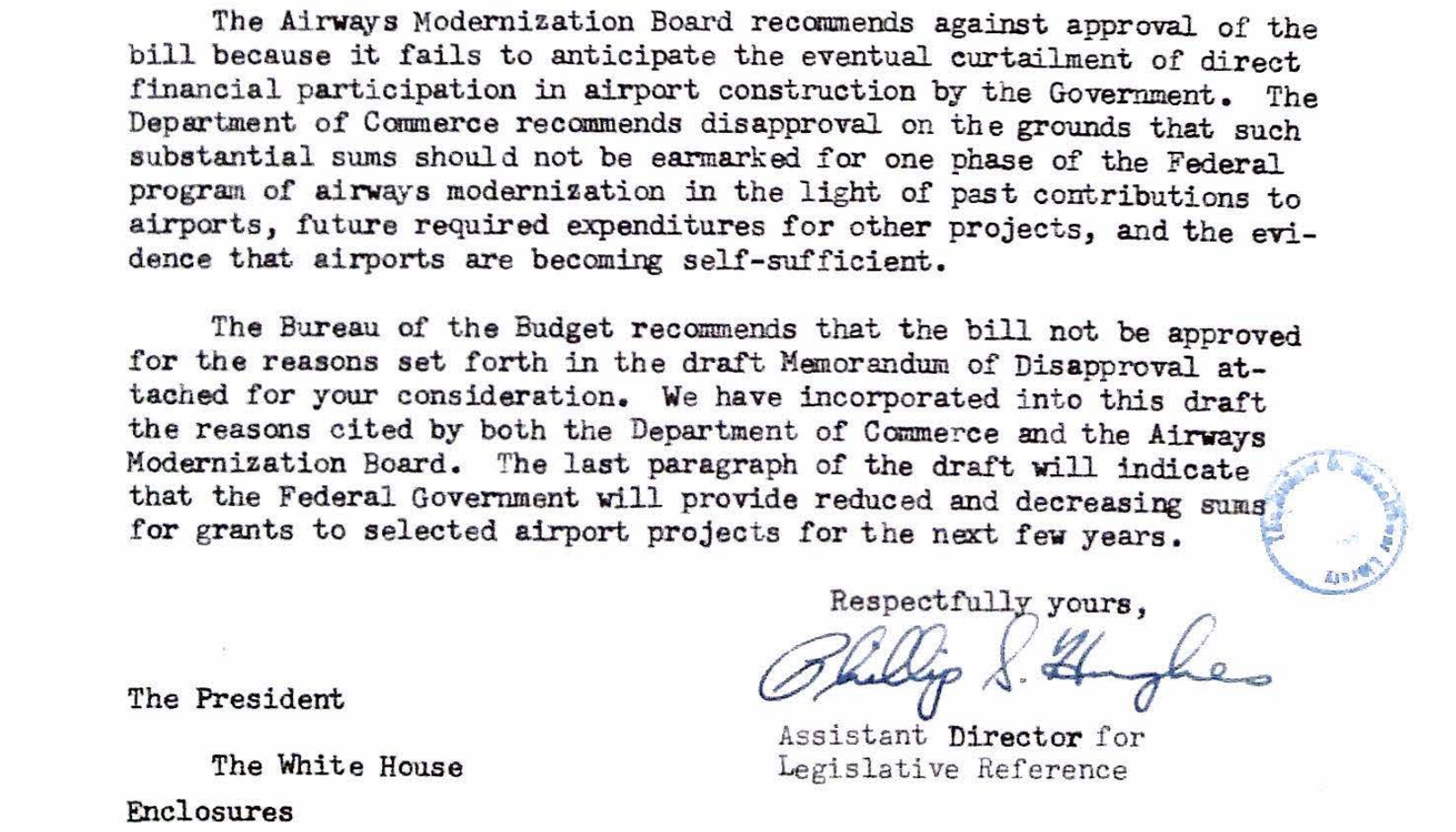

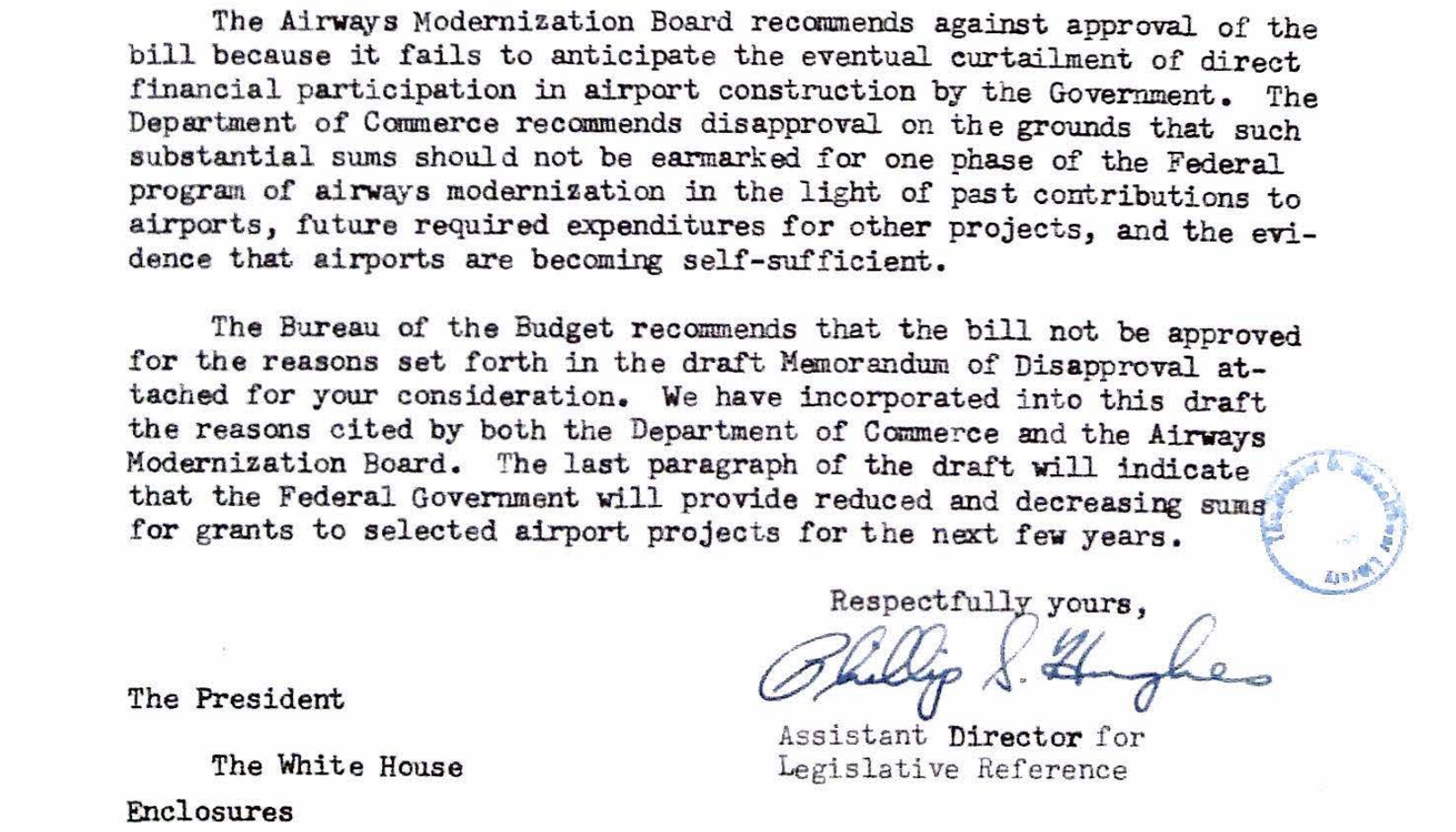

Three years later, Congress proposed a reauthorization bill proposing another increase – this one from $63 million per year to $100 million per year – and this time Budget, Commerce, and Quesada all recommended a veto, with Quesada stating “In the foreseeable future, it should be expected that more and more airports will become capable of self-support.”[22]

Because the bill was sent to the White House at the end of the session, Eisenhower was able to issue an unreviewable “pocket veto” of the bill on September 2, 1958. In his veto message, Eisenhower used a military metaphor: “I am convinced that the time has come to begin an orderly withdrawal from the airport grant program…others should begin to assume the full responsibility for the cost of construction and improvement of civil airports.”[23]

A version of the vetoed bill was re-introduced on the first day of the next Congress as S. 1, 86th Congress. The bill would have reauthorized the program for five years at an average of $115 million per year. The White House countered with a four-year proposal to taper the program off from $63 million per year to $35 million per year, an average of $50 million per year.[24]

In February, the Senate passed its bill (shortened to four years), but an amendment cutting funding down to the current law $63 million per year failed by a vote of less than two to one (35 yeas, 53 nays).[25] The House passed a bill providing an average of $74 million per year, but the House narrowly voted down an amendment to cut the House bill’s airport grant funding down to the President’s levels.[26] Eisenhower wrote to a friend the following day saying “The motion lost, but we picked up a surprising number of Democratic votes, and the Republican side stood – almost to a man – firm. That augurs well that any veto on such a bill will be sustained.”[27]

In House-Senate conference, the House position was $74 million per year over four years and the Senate position was $116 million per year over the same period (compared with the Administration proposal of $50 million per year and a current policy “flat-line” of $63 million per year). After almost three months of fruitless House-Senate negotiations, and facing a June 30 funding expiration and a looming veto threat from President Eisenhower, the Senate back-tracked on June 15 and settled for a two-year extension of the existing $63 million per year program, to which the House concurred.

Eisenhower signed the bill into law (73 Stat. 155) on June 29, and in his signing statement, the President emphasized that the FAA Administrator should prioritize the use of funding for safety projects.[28]

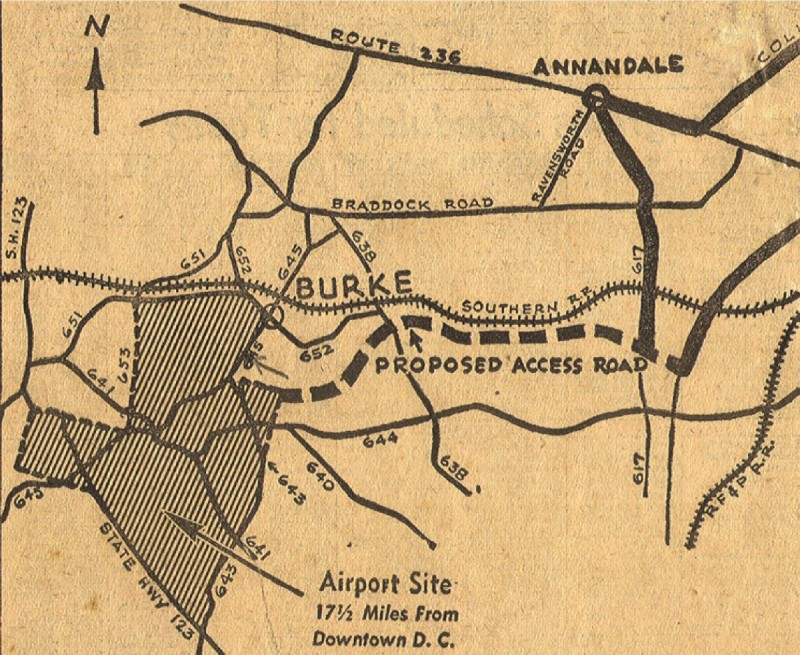

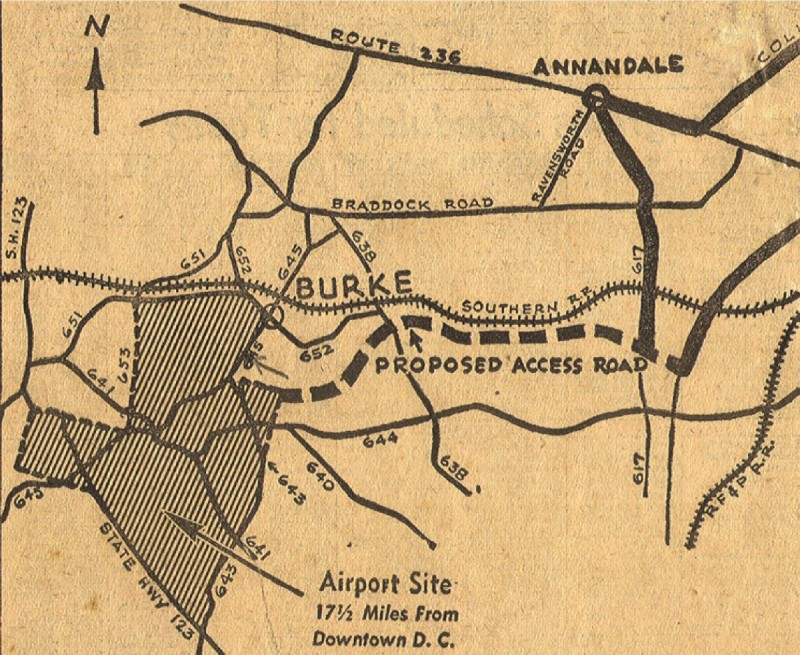

A second Washington-area airport

Airport aid to local governments was one thing, but the federal government had a special responsibility for the local affairs of the District of Columbia, which Eisenhower recognized. Washington National Airport had been experiencing capacity problems since the end of the war, but the CAA’s plan to build a reliever airport in Burke, Virginia was derailed by local opposition in 1952, and Congress and the CAA spent the next five years going back and forth between the Burke location, possible expansion of Baltimore Friendship Airport, and the possible conversion of Andrews Air Force Base to civilian use.[29]

Proposed reliever airport site in Burke, Virginia.

Eisenhower was personally drawn into the debate in mid-August 1957.[30] Later that month, Congress appropriated the first $12.5 million for construction of a new airport (before a site was chosen), on the condition that no money could be spent until the President recommended a site, and giving him a deadline a January 15, 1958. Eisenhower sent Quesada in fall 1957 to evaluate four sites – Friendship, Burke, and two other Virginia locations (Pender and Chantilly). Quesada chose Chantilly, and Eisenhower backed his decision and sent it to Congress. Congress then appropriated another $50 million for construction in August 1958.

After Secretary of State John Foster Dulles died in August 1959, it was Quesada’s idea to name the new airport after him, which Eisenhower did via executive order in July of that year.[31] The airport opened to the public in November 1962, and while it took longer than expected, by the 1990s, traffic at Dulles was outpacing that at National.

Airline finances and regulation

During the Eisenhower era, the economic regulation of the airlines was outside the scope of the President’s authority, being handled by the quasi-judicial Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). However, the CAB’s approval of routes, rates and carriers between the U.S. and foreign nations (and between the U.S. and its territories abroad) inherently included a foreign policy element, which is why the law allowed for the President to overrule the CAB’s decisions on some foreign cases. And, since the U.S. was unique at that time in lacking a government-owned “flag carrier” airline responsible for service to all foreign destinations, this put the President in the unusual position of sometimes having to pick and choose which private businesses would receive lucrative route monopolies and the government subsidies that came with them.

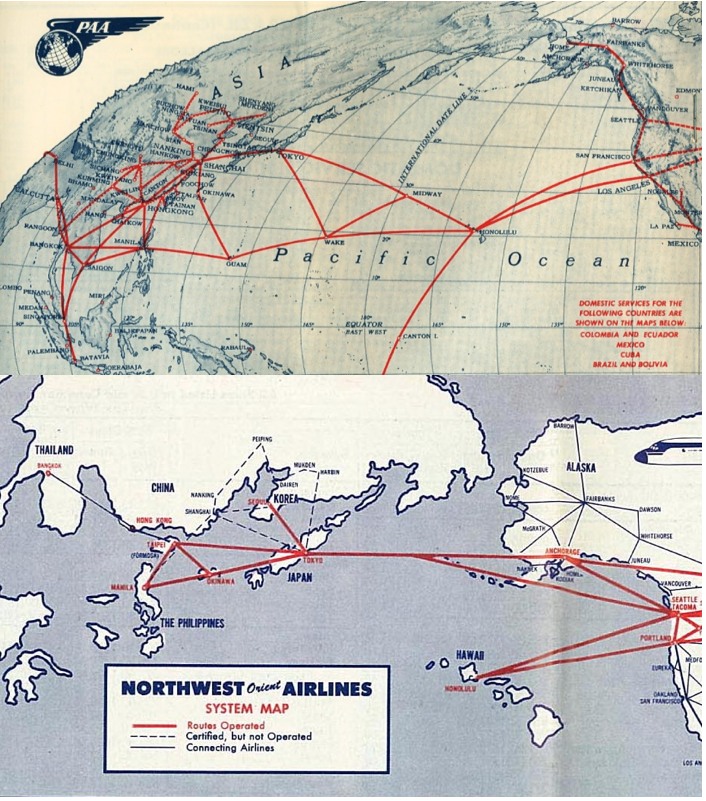

Eisenhower reaffirmed with his Commerce Secretary in September 1954 that he rejected the prewar policy of choosing Pan American Airways as the “chosen instrument” of the federal government, or the de facto flag carrier, and pointed to a recent CAB decision canceling Northwest’s routes to Hawaii while renewing Pan Am’s as “an example of something we should not do.”[32] But in that letter, the President also expressed uncertainty as to the criteria that should be used when choosing between carriers seeking to serve the same routes, and throughout his terms of office, he was sometimes inconsistent in applying criteria.

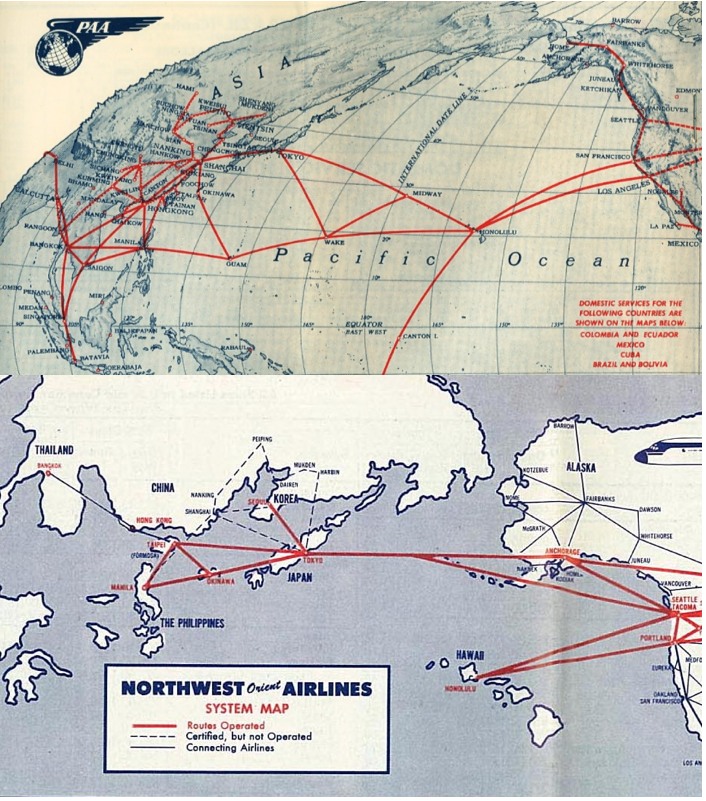

Issues relating to air service between the U.S. and Asia forced Eisenhower’s intervention on multiple occasions.[33] Since just after the end of the war, Pan American had been operating exclusive routes from several West Coast stops to Tokyo and Manila, with refueling stops in Honolulu and either Midway or Wake Island. But Northwest Airlines had the much shorter (and thus more fuel-efficient) “Great Circle Route” between the U.S. and Japan (with two routes: Minneapolis-Tokyo, with refueling stops in Alberta and Anchorage, or Seattle-Tokyo, with a refueling stop in the Aleutian Islands).

Pacific route maps for Pan Am (above) and Northwest (below) in the mid-1950s.

Pan Am wanted to compete directly with Northwest on the Great Circle Route, and Northwest wanted to compete through Hawaii, and both applied to the CAB for permission. The Board voted to grant that permission in December 1955, but President Eisenhower wrote to the Board on February 1, 1955 asking them to “hold in abeyance my decision concerning the use of the great circle route by Pan American pending further study and later report” on eventual non-stop service between the U.S. and Asia.[34]

Then, on February 5 (a Saturday), Eisenhower met with the chairman of the CAB, the Commerce Secretary, and a Congressman and Senator from Minnesota to discuss Northwest, and on February 7, Eisenhower revised his order with regard to Northwest getting to keep its temporary Hawaii service. The President explained himself at his February 9 press conference, saying that he was charged by Congress with reducing the amount of subsidies paid to air carriers, and that increasing competition was a competing consideration. He said that he made the decision to cut Northwest’s Hawaii route because Pan Am had more traffic and fewer subsidies, but that the CAB chairman had come to him and “pointed out that all of their calculations showed that within 2 years, they believed, the entire subsidy would be eliminated from the Pacific runs,” so he reversed himself and allowed Northwest to keep Hawaii service temporarily for three years.[35]

(It was Eisenhower who had finally taken airline subsidies out of the Post Office air mail budget, through Reorganization Plan No. 10 of 1953, and vested it completely within the CAB, which he said would give a more accurate presentation of the cost and allow Congress to control overall subsidy funding in the annual appropriations process.[36] Partly as a result of this change, airline subsidies for non-local service in the contiguous 48 states dropped to zero by the end of Eisenhower’s term.[37])

In January 1956, Eisenhower asked the CAB to reopen the Great Circle case, even though there was not yet the jet capacity for nonstop service, “in the light of any new and relevant circumstances or developments that it finds to exist,” and the case was reopened.[38] On May 3, 1957, the CAB decided to grant Pan Am a Great Circle Route, but from California (not stopping in the Pacific Northwest).

On July 2, 1957, Eisenhower wrote to Commerce Secretary Weeks to say that an old friend who was on the board of directors of Northwest had come to the Oval Office for a visit to say he was “violently opposed” to Pan Am being allowed to compete on the route, and “gave me a number of statistics and arguments to support his view.” He asked Weeks to perform an independent analysis so “when we have to make a decision on the situation, no matter which way it goes, we do it with all the available facts before us.”[39]

One month later, Eisenhower backed the CAB‘s decision, but later had second thoughts. On September 2, Eisenhower asked his staff if the fact that Northwest was limited to just seven landings on Tokyo per week meant that their monopoly might deprive some parts of the U.S. from direct Great Circle access, and whether it “would seem logical for us to recall our action” on the case, noting that the law gave him one month to modify his approval of CAB actions.[40] The next day, Eisenhower notified the CAB that he was temporarily deferring his decision, and wanted updated traffic statistics between the U.S. and Japan.[41] Those were forthcoming, and the CAB reaffirmed its decision in December 1957, which was approved by Eisenhower in February 1958.

One year later, Eisenhower wrote to the CAB, declaring that “this Administration is firmly committed to the view that the public interest requires competitive American flag service at the earliest feasible date on all international air routes serving major United States Gateways. With such competition the benefits to the Nation of international air transportation – increased trade and friendly relations abroad – become the greater.” Accordingly, he asked the CAB to “initiate a proceeding consolidating all Pacific air route matters into a single record” and make recommendations quickly.[42] This became known as the Transpacific Route Case.

It took until December 1960 for the CAB to reach a decision, and the Board decided in favor of multiple new entrants to the Pacific routes. Northwest and Pan Am would be able to almost completely duplicate each other’s routes on all stops on both the Great Circle and Central Pacific trajectories, with greater point-to-point service in the Far East and a connection in Hong Kong with TWA’s service coming from Europe and Central Asia. The Board also recommended significant new entrant access to Hawaii.

Two days before the end of his term of office, Eisenhower vetoed the new service aspects of the Board’s plan. In his letter to the Board (which is the very last document in the Eisenhower volumes of Public Papers of the Presidents), he said that “our foreign relations would be adversely affected were we at this time to add second carriers on our major routes to the Orient. Duplication of service on major routes presently served by a single carrier means inevitably – as history shows – that greater United States flag capacity will be offered…approval of the Board’s major recommendations in this case would unsettle our international relations – particularly with Japan which would be faced with an additional United States carrier on all but one of the now existing four routes from the United States to Tokyo.”[43]

Presidential authority to overrule the CAB on service decisions between the contiguous U.S. states and Alaska and Hawaii ability ended when those territories achieved statehood in 1959, but Eisenhower also expressed his hope that the Board would reconsider the expanded U.S.-Hawaii service as well, which they did (but one of the new entrants challenged that decision, successfully, in court).

The Administration was also keeping an eye on airline finances and how their spending affected what we now call the aerospace manufacturing sector. The economic downturn that started in 1957 had affected the bottom line of most carriers, just as they were engaged in massive capital investment programs to switch their fleets over from piston engines to turbojets.

In late April 1958, the President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization (including Milton Eisenhower) met with the President to discuss a number of things, including the need for a study of how the financial crisis was affecting the airline fleet changeover. Quesada recruited Harvard Professor Paul Cherington to conduct the study, which took two months. (Cherington would later go on to become an Assistant Secretary of Transportation under President Nixon.)

Cherington’s report found that U.S. airlines had begun a massive capital spending plan totaling $2.8 billion over the upcoming five years, but that because of the recession, credit was tight and “many airlines are encountering significant difficulties in securing the necessary financing. It is doubtful that a number of domestic carriers, presently accounting for about 28 percent of the industry traffic volume, will be able to complete necessary financing under anything approaching normal credit conditions.”[44]

The Cherington report was the subject of a July 1958 Cabinet meeting, at which “It was noted several times throughout the discussion that the CAB had been dragging its feet on rate adjustments which might permit the airlines to set more realistic rates on peak traffic and more attractive rates on off-hours traffic, thus increasing the load factor and fiscal soundness of the airlines.”[45]

The Cabinet decided that since most of the actions that needed to be taken were CAB responsibility, the Cherington report should be submitted to Congress and shared with the public as a general show of interest, to hopefully nudge the CAB in the right direction. The final report was sent to Congress on August 5.

[1] Executive Order 9781, September 19, 1946, as amended by Executive Order 10360, June 11, 1952, and Executive Order 10655, January 28, 1956.

[2] Bradley H. Patterson, Jr., “Teams and Staff: Dwight Eisenhower’s Innovations in the Structure and Operations of the Modern White House.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, vol, 24, No., 2, Spring 1995, pp. 277 (quote is on p. 289, Quesada is identified in footnote 24).

[3] Letter from Nelson Rockefeller to Laurence Rockefeller, January 20, 1955. Located in U.S. President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization (Rockefeller Committee): Records, 1953-61; Box 22, folder entitled “No. 179 Aviation Facilities 1955-57 Harding and Curtis Study,” Eisenhower Library.

[4] Aviation Facilities Study Group. Aviation Facilities: The Report of the Aviation Facilities Study Group to the Bureau of the Budget, December 31, 1955. Quote from p. 3.

[5] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Letter to Edward P. Curtis on His Appointment as Special Assistant to the President for Aviation Facilities Planning, February 11, 1956. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1956. Document 38 on p. 252.

[6] Curtis’s interim report and related Cabinet meeting information are located in DDE’s Papers as President, Cabinet Series, Box 8, folder entitled “Cabinet Meeting of April 5, 1957,” Eisenhower Library.

[7] The reports are Aviation Facilities Planning: Final Report by the President’s Special Assistant (Washington: GPO, 1957), together with National Requirements for Aviation Facilities: 1956-75 (final report prepared by Airborne Instruments Laboratory, Aeronautical Research Foundation, and Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory for Edward P. Curtis, Special Assistant to the President for Aviation Facilities Planning) and A Plan for Modernization of the National System of Aviation Facilities by the Systems Engineering Team of the Office of Aviation Facilities Planning, The White House.

[8] Aviation Facilities Planning: Final Report by the President’s Special Assistant – demand stats are on p. 5 and quote is from p. 2.

[9] Ibid p. 20.

[10] The bills were H.R. 12616 and S. 3880 of the 85th Congress.

[11] U.S. Senate. Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. “Federal Aviation Act of 1958” (report to accompany S. 3880), Senate Report No. 1811, 85th Congress, 2nd Session, p. 9.

[12] L.A. Minnich, Jr. “Minutes of Cabinet Meeting – June 6, 1958.” Located in DDE’s Papers as President, Ann Whitman File, Cabinet Series, Box 11, “Cabinet meeting of June 6, 1958” folder; Eisenhower Library.

[13] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to the Congress Recommending the Establishment of a Federal Aviation Agency, June 13, 1958. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1958. Document 135 on p. 466.

[14] All quotes in this paragraph from Aviation Facilities Planning: Final Report by the President’s Special Assistant pp. 36-38.

[15] Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1959, pp. M30-M31.

[16] Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1960 p. M12.

[17] Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1961 p. M12.

[18] John F. Kennedy. Special Message to the Congress on the Federal Highway Program, February 28, 1961. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kenney, 1961 as document 58 beginning on p. 126 (quote from p. 131).

[19] Airport Panel of the Transportation Council of the Department of Commerce. The National Airport Program: Report on the Growth of the United States Airport System. Reprinted as Senate Document 95, 83rd Congress, 2nd Session.

[20] Memorandum from the Bureau of the Budget to President Eisenhower, July 29, 1955. Located in White House Office: Record Officer Reports to the President on Pending Legislation, 1953-61, Box 57, folder entitled “Appr. 8/3/55 To amend FED. AIRPORT Act, as amended. S. 1855,” Eisenhower Library.

[21] Public Law 211 of the 84th Congress, 69 Stat. 441.

[22] Memorandum from E.R. Quesada to Philip S. Hughes, Bureau of the Budget, August 21, 1958. Located in White House Office: Record Officer Reports to the President on Pending Legislation, 1953-61, Box 143, folder entitled “Vetoed 9/3/1958 To amend the FEDERAL AIRPORT ACT in order to extend the time for making grants under the provisions of such Act, and for other purposes. S. 3502,” Eisenhower Library.

[23] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Memorandum of Disapproval of Bill To Amend the Federal Airport Act, September 2, 1958. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1958. Document 246 on p. 673.

[24] Text of the competing proposals in found in U.S. Senate. Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Federal Airport Act, 1959 (Hearings on S. 1, 86th Congress, 1st Session), January 1959, pp. 1-6.

[25] Congressional Record (bound edition), February 6, 1959, p. 2045.

[26] Roll call No. 19 of 1959, Congressional Record (bound edition), March 19, 1959 p. 4665.

[27] Dwight D. Eisenhower letter to Henry Junior Taylor, March 20, 1959. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, volume 20, document 1114 beginning on p. 1422.

[28] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Statement by the President Upon Signing Bill Amending the Federal Airport Act, June 29, 1959. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1959. Document 143 on p. 483.

[29] As best described in Stuart A. Rochester, Takeoff at Mid-Century: Federal Civil Aviation Policy in the Eisenhower Years 1953-1961 (Washington: GPO, 1976).

[30] Eisenhower’s August 15, 1957 meeting with Sen. Spessard Holland (D-FL) is recounted in Eisenhower’s Memorandum for the Record of that date. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, volume 18, document 288 beginning on p. 369.

[31] Executive Order 10828, July 15, 1959.

[32] Dwight D. Eisenhower, letter to Sinclair Weeks marked “Personal,” September 28, 1954. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, volume 15, as document 1080 on page 1316.

[33] For a scholarly overview, see Lucile Sheppard Keyes, “The Transpacific Route Investigation: Historical Background and Some Major Issues,” Journal of Air Law and Commerce, vol. 34, Issue 1, 1968.

[34] Letter quoted in Civil Aeronautics Board Reports, vol. 20, February 1955-May 1955, pp. 47-48.

[35] Dwight D. Eisenhower, The President’s News Conference of February 9, 1955. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1955. Document 33 on p. 251 (quote from p. 260).

[36] Dwight D. Eisenhower. Special Message to the Congress Transmitting Reorganization Plan 10 of 1953 Concerning Payments to Air Carriers, June 1, 1953. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953 as Document 94 on p. 360.

[37] John W. Fischer and Robert S. Kirk. Aviation: Direct Federal Spending, 1918-1998. Congressional Research Service Report RL30050, February 3, 1999. Retrived online September 2, 2020 at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL30050.pdf

[38] Dwight D. Eisenhower. Letter to Ross Rizley, Chairman, Civil Aeronautics Board, on the Great Circle Route to the Orient, January 18, 1956. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1956. Document 14 on page 158.

[39] Memorandum to Sinclair Weeks, July 2, 1957. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, volume 18, as document 224 on page 288.

[40] Dwight D. Eisenhower, memorandum to Gerald Demuth Morgan, September 2, 1957. Reprinted in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, volume 18, as document 315 on page 406.

[41] Letter quoted in Civil Aeronautics Board Reports, vol. 26, October 1957-June 1958, p. 481 in footnote 1.

[42] Letter from Dwight D. Eisenhower to James R. Durfee, February 18, 1959. Quoted in Civil Aeronautics Board Reports, vol.32, October 1960-January 1961, pp. 1034-1035.

[43] Dwight D. Eisenhower. Memorandum Concerning the Trans-Pacific Route Case, January 19, 1961. Reprinted in Public Papers of the Presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960-1961. Document 436 beginning on page 1064.

[44] “The Status and Economic Significance of the Airline Equipment Investment Program pp. i-ii. Located in DDE’s Papers as President, Ann Whitman File, Cabinet Series, Box 11, folder entitled “Cabinet Meeting of July 7, 1958,” Eisenhower Library.

[45] Minutes of Cabinet Meeting – July 7, 1958, p. 3. Located in DDE’s Papers as President, Ann Whitman File, Cabinet Series, Box 11, folder entitled “Cabinet Meeting of July 7, 1958,” Eisenhower Library.

While Curtis was working, the worst civil aviation disaster in U.S. history to that point took place – a mid-air collision of two passenger airliners over the Grand Canyon, killing all 128 persons on both planes on June 30, 1956. The investigation revealed that better air traffic control would almost certainly have prevented the accident. Accordingly, before his full investigation was finished, Curtis issued an

While Curtis was working, the worst civil aviation disaster in U.S. history to that point took place – a mid-air collision of two passenger airliners over the Grand Canyon, killing all 128 persons on both planes on June 30, 1956. The investigation revealed that better air traffic control would almost certainly have prevented the accident. Accordingly, before his full investigation was finished, Curtis issued an