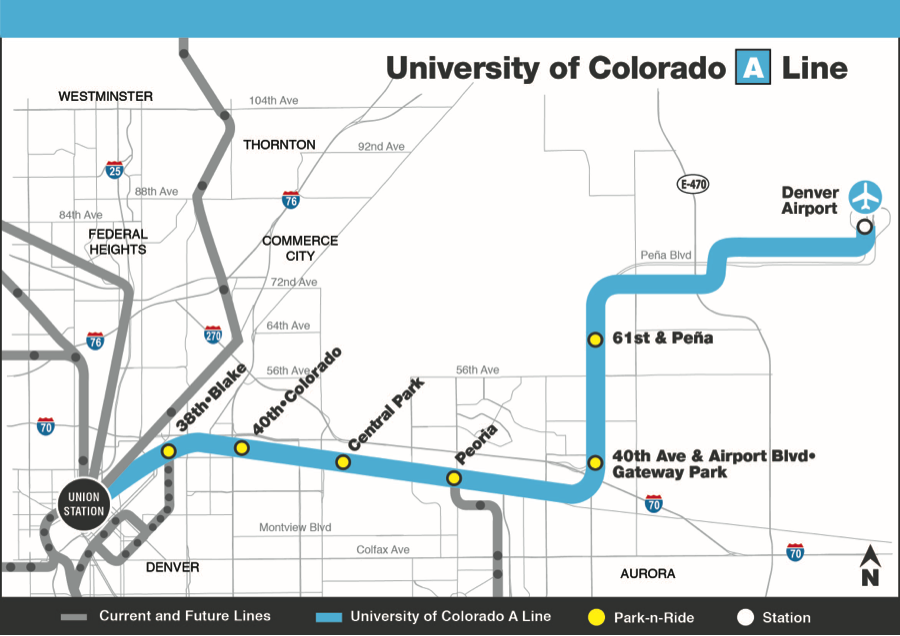

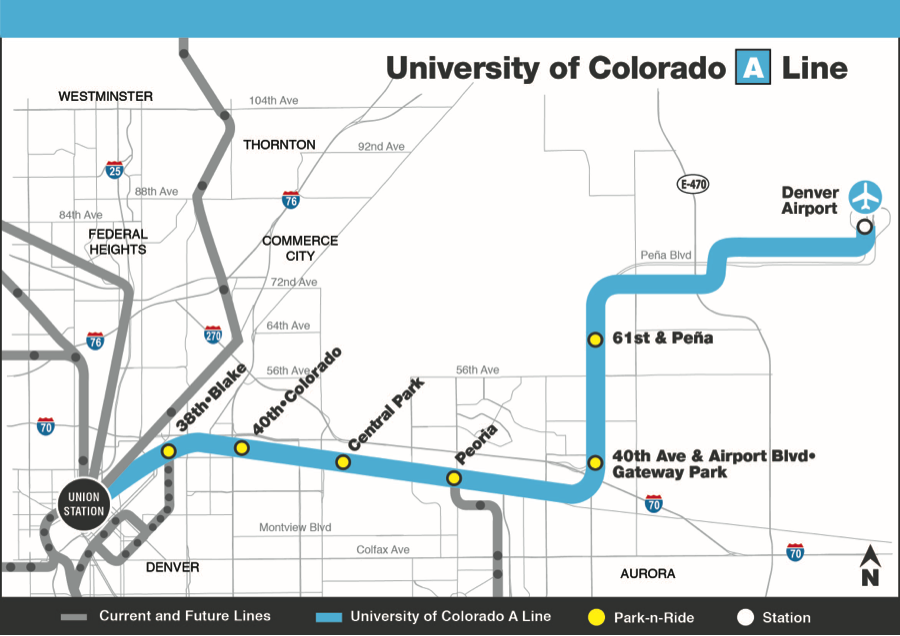

The nation’s first modern public-private partnership (P3) for public transportation has now begun operations. On April 22, 2016, the Denver Regional Transportation District (RTD) opened the new University of Colorado A Line that connects Denver’s International Airport to Union Station downtown. As an innovative example of a P3, it is a project that Eno is especially interested in; and you should be too.

Source: RTD website

RTD will open three more Eagle P3 commuter rail lines throughout this year, connecting downtown with the neighboring suburbs. This project is actually part of the larger FasTracks program, which includes 122 new miles of commuter and light rail lines, 18 miles of bus rapid transit, and thousands of transit-adjacent parking spaces.

Unique among transit lines in the U.S., the Eagle P3 uses a new approach to designing, building, and operating the transit lines. The private consortium Denver Transit Partners, led by the Fluor Corporation, entered into a 34-year agreement with RTD: five years to design and build, then 29 years to operate and maintain. This has enabled the private sector to assume some of the risks associated with the delivery of new infrastructure, and has played a large part in reducing overall costs and expediting timelines. While there are few transit projects for comparison, several elements make the Eagle P3 an especially interesting one.

Transit P3s

On a national level, transit P3 projects are far less common compared to other transportation ventures like toll roads. (In this case, we are referring to transit P3s that are design-built-finance-operate-maintain, not just design-build.) The P3 aspect is especially notable because this has been the first and only transit P3 in the U.S. to reach financial close. The only other major ongoing transit P3 is the Purple Line in Maryland, which was only approved earlier this month and is expected to reach financial close in June.

Back in 2007, the Federal Transit Administration attempted to spur more transit P3 activity through its Public-Private Partnership Pilot Program (Penta-P), which aimed to test P3s as an alternative form of project delivery. Three pilot projects were ultimately selected, but only the Eagle P3 proceeded towards financial close. The other two projects under Penta-P were the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Oakland Airport Connector and Houston’s North and Southeast Corridor bus rapid transit line. While the BART Connector was originally conceived as a P3, it was eventually completed under a design-build-operate-maintain model (i.e. without a financing component).

Part of the challenge contributing to the lack of transit P3s is that, unlike some toll roads, transit projects do not provide adequate revenue streams to cover the full operating costs. That makes it difficult for the private partner (known as the concessionaire) to support the financing based exclusively on farebox revenue, as well as handling operations and maintenance for several decades.

For the Eagle P3, RTD used a mix of funding, including RTD capital funds, federal grants, and a dedicated portion of regional sales tax revenues, as well as financing. While the terms “funding” and “financing” are often used interchangeably, they in fact mean two different things. Put simply, funding usually does not need to be paid back, while financing does. (Eno explains this difference more fully in our P3 report, Partnership Financing.)

Instead of using tolls or farebox revenues to pay back bonds, RTD is using the “availability payment” model, where RTD provides a recurring payment to the concessionaire. In turn, the concessionaire must meet specific milestones and performance standards established during the contract negotiations. This also means that if the concessionaire fails to meet certain standards, there is a financial penalty. In other words, the availability payments provide a revenue stream for the concessionaire and a tool for the public agency to incentivize the concessionaire to operate and maintain the project. There are few industry examples for comparison; the first U.S. transportation P3 project to use availability payments was the Interstate 595 corridor improvement in Florida, which opened to users in 2014.

RTD established the performance standards during the Eagle P3 project planning process, as outlined in their Procurement Lessons Learned document. Rather than list required design specifications for bidding companies, RTD established overarching performance standards. The bidders were then able to design the project as they wish, as long as it met those standards. RTD found that if they had the bidders only comply by design specifications, the resulting project might not be the most efficient product. (With that said, RTD mentioned in their Lessons Learned document that they had encountered challenges in attracting a sufficient amount of bidders and generating the competition that makes P3s appealing to public agencies.)

It is probably too early to tell whether the Eagle P3 signals a wave of other transit public-private partnerships across the country. It is important to remember the industry idiom, “When you’ve seen one P3, you’ve seen one P3.” However, the project could provide a demonstrable example of how a transit P3 could succeed.

Other cities and metropolitan areas should note that part of the reason why the Eagle P3 was able to happen in the first place is due to the success of Denver’s T-REX project. T-REX was a design-build project completed on time and on budget, which helped build the public’s trust in RTD. For the long term, ensuring public trust is important because it goes beyond any one project.

In their Lessons Learned document, RTD notes the benefit of its past experience with the T-REX project and (very briefly) that RTD’s experience in contracting out bus operations helped with the P3 development process. Also important is the RTD leadership under then-General Manager Philip Washington (also a former member of the Eno Board of Directors). Washington and other senior management prioritized the project; the success of the Eagle P3 to reach financial close reflects that executive-level support.

The role of internal processes and institutional knowledge, as well as the support of executive leadership, were crucial for the project to take off at the beginning and will be crucial in how the Eagle P3 operates. Other transit agencies owe it to themselves to understand these lessons and how they can be applied to other transit projects in the future.

However, this is only the beginning of this project as a P3. In addition to the other commuter lines opening this year, there is the remaining 29 years of operations and maintenance. Eno will continue to monitor the evolution of this project, and how it will impact transportation P3s as a whole.