September 19, 2017

Metro (the operating name of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) faces challenges in both its operating budget and its separate, multi-year capital budget. The details of the operating budget were made clear before a September 14 meeting of the WMATA Board of Directors Finance Committee. The committee was presented with the final results of Metro’s fiscal year 2017 budget, which closed on June 30.

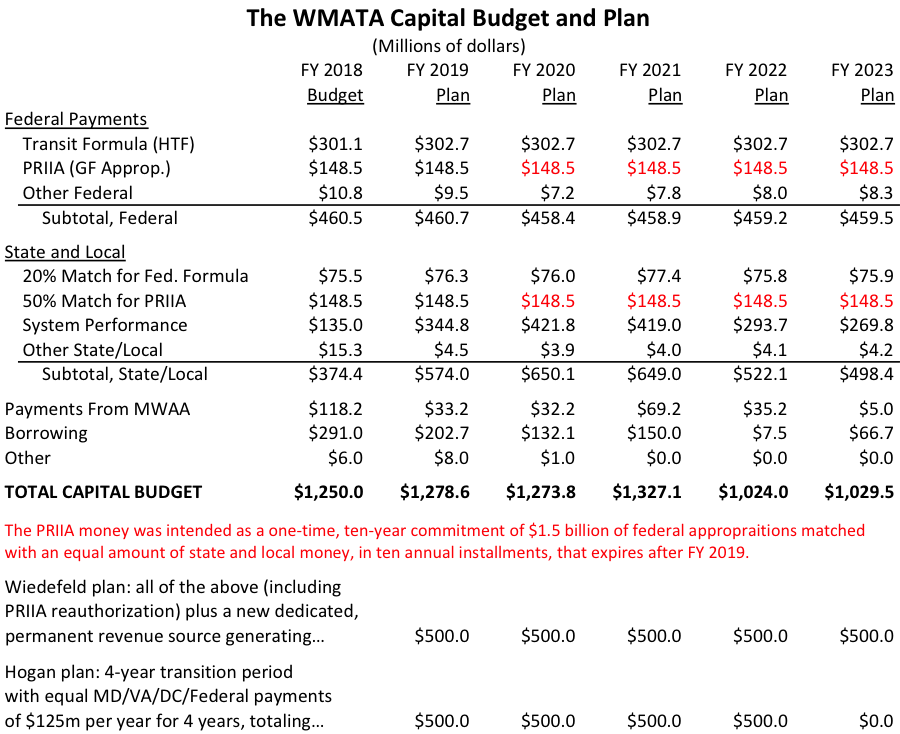

WMATA had assumed $900 million in operating revenue in 2017 but only took in $784 million, a shortfall of $116 million, or 13 percent below budget. This is largely due to ridership being 12% below the budgeted expectation. The 2018 forecast does not show any increase in ridership, so the 2018 operating revenue forecast may be more realistic. But the realistic revenue forecast also forces the operating subsidy contributed by local political jurisdictions to increase by $119 million, or 14 percent.

The WMATA Operating Budget

|

| (Millions of dollars) |

|

|

FY 2016 |

FY 2017 |

FY 2017 |

FY 2018 |

|

|

7/1/15 – |

7/1/16 – |

7/1/16 – |

7/1/17 – |

|

|

6/30/16 |

6/30/17 |

6/30/17 |

6/30/18 |

|

|

Actual |

Budgeted |

Actual |

Budgeted |

| Ridership (Thousands) |

|

|

|

|

|

Metrorail |

191,348 |

203,500 |

176,972 |

178,505 |

|

Metrobus |

127,432 |

135,598 |

121,732 |

116,968 |

|

MetroAccess |

2,281 |

2,420 |

2,368 |

2,400 |

|

Total |

321,060 |

341,518 |

301,072 |

297,873 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Operating Revenue (Mil. $) |

|

|

|

|

|

Metrorail |

$574 |

$613 |

$522 |

$538 |

|

Metrobus |

$141 |

$152 |

$129 |

$146 |

|

MetroAccess |

$9 |

$10 |

$10 |

$10 |

|

Parking |

$45 |

$47 |

$41 |

$42 |

|

Non-Passenger |

$82 |

$61 |

$64 |

$59 |

|

Total |

$900 |

$900 |

$784 |

$845 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Operating Expenses (Mil. $) |

$1,745 |

$1,745 |

$1,644 |

$1,825 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Operating Subsidy |

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia jurisdictions |

$214 |

$213 |

$213 |

$251 |

|

Maryland jurisdictions |

$319 |

$320 |

$320 |

$364 |

|

District of Columbia |

$312 |

$312 |

$312 |

$365 |

|

Prior Year Surplus |

$0 |

$0 |

$16 |

$0 |

|

Total |

$845 |

$845 |

$861 |

$980 |

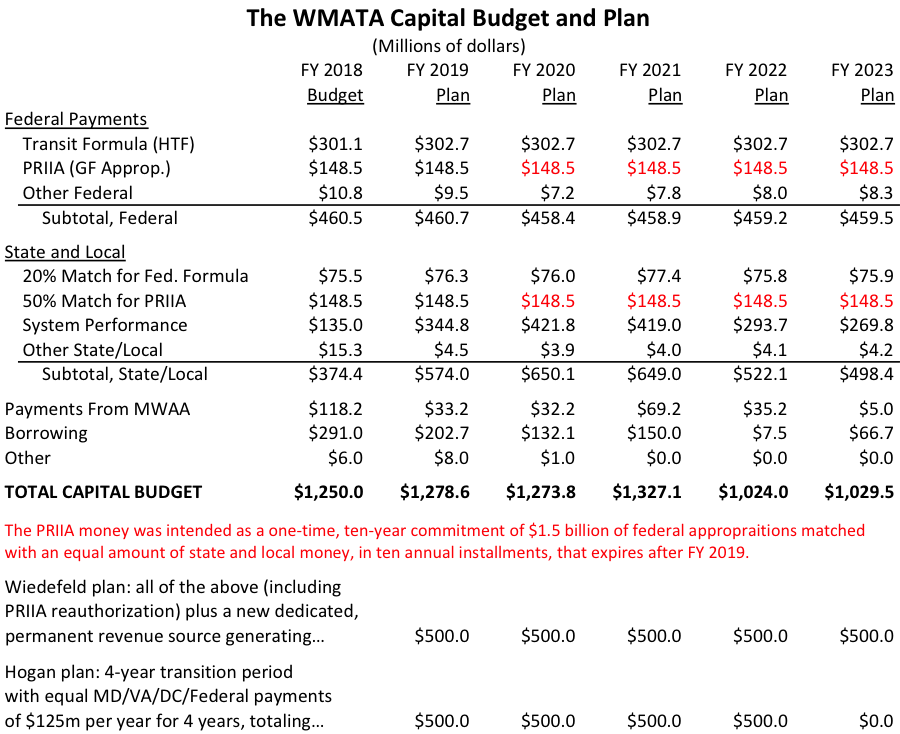

But the larger financial needs are on the capital side of the budget, not the operating side. General Manager Paul Wiedefeld told the governors of Maryland and Virginia and the Mayor of the District of Columbia in August that, even if Congress renews the PRIIA funding authorization of $150 million per year for WMATA capital after its scheduled expiration in 2019, there would still be an additional $500 million per year needed to prevent the capital backlog from getting worse.

At the August meeting, Wiedefeld proposed that local jurisdictions collectively impose new dedicated tax revenues of some kind to total $500 million per year, in perpetuity, to be dedicated to metro capital spending. News from the closed-door meeting soon leaked to the Washington Post, which reported that Maryland Governor Larry Hogan (R) vetoed the idea of any dedicated revenue from Maryland. (The leaks to the Post were anonymous, but appeared to come from WMATA itself.)

After two weeks of bad press, Hogan did an about-face, proposing that Maryland, Virginia, DC and the federal government each contribute $125 million per year for four years as an interim capital supplement for WMATA while they figured out a long term revenue strategy.

Weidefeld then made a presentation to the WMATA Finance Committee last week indicating possible acceptance of Hogan’s plan as an interim measure.

To confuse matters further, the chairman of the WMATA Board said earlier this week that Wiedefeld’s estimates of Metro’s long-term capital needs were too low – about $1 billion per year too low. (Wiedefeld’s presentation was based on a 10-year, $15 .5 billion capital plan, but Board Chairman Jack Evans (D) now says $25 billion over 10 years is more appropriate.)

(Ed. Note: The Post article contains this factoid that may be indicative of Evans’s thought process: “Evans was unable to attend Thursday’s board meeting because he joined a regional delegation in Japan to explore the feasibility of a high-speed magnetic levitation passenger train from the District to New York City.”)

And as with any discussion of another round of extra funding for WMATA, the subject of who gets to spend the money invariably comes up. Former US Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood was hired by Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe (D) in March of this year as a consultant on WMATA revitalization. LaHood’s initial recommendations have not yet been made public, but the same leaks from the earlier meetings indicated that LaHood is proposing that the WMATA Board of Directors, which currently has eight voting members (two each from Maryland, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and the federal government), temporarily shrink to a five-voting-member “Reform Board.” It is unclear if the current Board has the legal authority to shrink itself, and amending the interstate compact that governs the Board’s structure could take up to two years.

(Ed. Note: LaHood should probably stop using the term “Reform Board,” as it has a bad history. In December 1997, the Republican Congress passed a major Amtrak reform law. Section 411 of the law abolished the existing Amtrak Board of Directors and replaced it with a new “Reform Board” which was supposed to have the independence to fix Amtrak’s problems and which was required to get Amtrak to financial self-sufficiency, on an operating basis, within five years. And everyone remembers how the Reform Board did its job and Amtrak has operated on a break-even basis since 2002, right? What’s that, you say? Amtrak has required operating subsidies from Uncle Sam in every year since 2002, including a requested $684 million in operating subsidies in FY 2018? Yes, indeed. The reforms approved by the Reform Board were much more limited than bill sponsors had hoped (some say this is because President Clinton’s appointees to the Reform Board were not reform-minded), and the five-year deadline came and went with continued annual Amtrak subsidies, which endure to this day. In 2008, section 202 of the PRIIA law quietly converted the Reform Board back to a regular Board of Directors. This is not, presumably, the image that LaHood wants to conjure for his Reform Board.)