This week, Congress passed another round of coronavirus response legislation, this bill (H.R. 266) providing another $483 billion in aid, bringing the net total amount provided to date to $2.4 trillion. (The gross total includes the face value of loans and is closer to $3.3 trillion, but almost all of those non-convertible loans are expected to be repaid within a decade.) The bulk of the money provided in this week’s bill is to beef up the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) loans-that-turn-into-grants for small businesses.

Even though H.R. 266 is the fourth coronavirus response bill sent to President Trump’s desk for signature, Congress is considering it the second half of the third round of legislation. According to Democratic leaders, round 1 (March 6) was preparedness, round 2 (March 18) was about virus testing and health care supplies, and round 3 (March 27 and this week) was about mitigation of the effects that the disease and its responses are having on individuals and the economy.

| Bill |

10-Year Deficit Increase (CBO) |

| Phase 1 (H.R. 6074) |

$8 billion |

| Phase 2 (H.R. 6201) |

$192 billion |

| Phase 3 (H.R. 748) |

$1.759 trillion |

| Phase 3.5 (H.R. 266) |

$483 billion |

| TOTAL |

$2.443 trillion |

By all accounts, round 4 will be about economic recovery, and Democratic leaders have indicated that their top priority in phase 4 will be financial aid to state and local governments, which have seen many of their revenue streams contract significantly in the last two months, even though their costs are increasing. (FYI, the smartest take on phase 4 we have seen is from Tony Fratto on Twitter: “Good public policy would treat PPP as an entitlement program with limitless funds. But the best way to make sure that a Phase 4 deal gets done is to keep PPP chronically underfunded.”)

This week, the National Governors Association sent a letter to Congress reiterating their earlier request that “Congress must appropriate an additional $500 billion, specifically for states and territories, in direct federal aid that allows for replacement of lost revenue.”

The phase 3 bill (the CARES Act) provided $150 billion in grants to states (of which large localities were eligible for a part of their state’s share), given out on a largely population-based formula explained here. Per the Daily Treasury Statements, $95.2 billion of that has already gone out the door in the April 15-22 period. In addition, the Federal Reserve created a $500 billion stopgap program to buy short-term municipal debt (explained by former transportation reporter Kellie Mejdrich here), but states want money they don’t have to pay back, not more loans.

Separately, the state departments of transportation collectively asked Congress for $50 billion just to replace dedicated transportation revenues that are anticipated to vanish due to coronavirus-driven demand reduction. It is unclear whether the governors and state DOTs consider the $50 billion part of the larger $500 billion, or in addition to it.

Should state governments get to decide how much of any hypothetical federal relief money goes to their transportation departments, or should Congress take that decision from them?

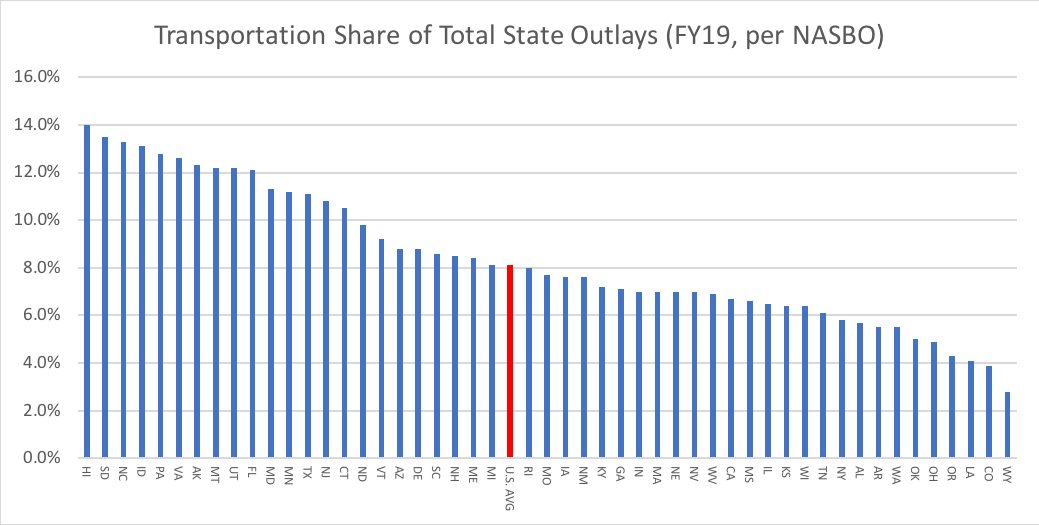

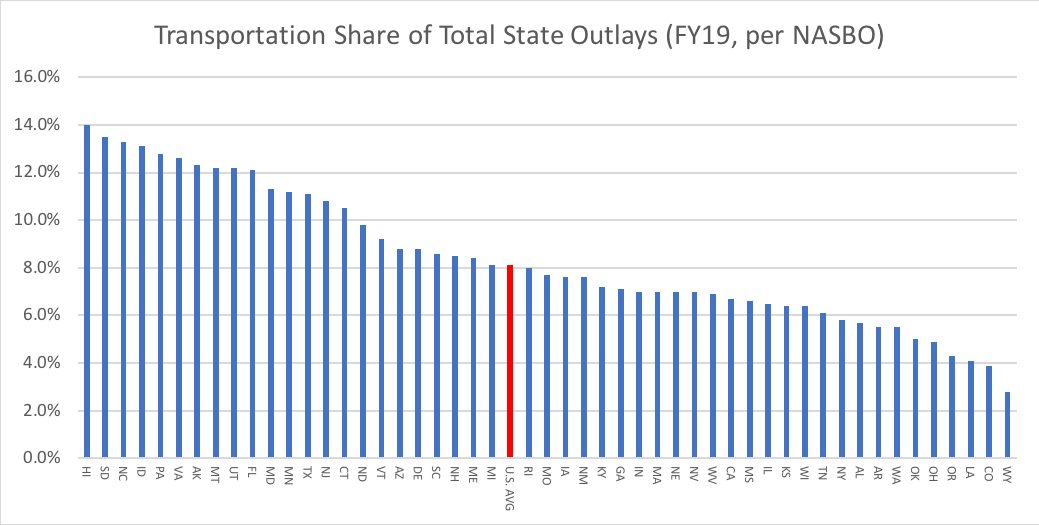

Following Justice Brandeis’s famous aphorism that states are “laboratories of democracy” where different policies may be tried out, the 50 state governments have placed widely divergent priorities on just how much of their total state spending should go towards transportation. According to the 2019 State Expenditure Report from the National Association of State Budget Officers (tables 38 and 39), estimated FY 2019 spending on transportation (capital-inclusive) ranged from 14.0 percent of Hawaii’s total spending down to just 2.8 percent of Wyoming’s total budget:

The accumulation of many differing spending and revenue priorities over the years also shows up in the general fiscal picture for a state, and there is also a wide discrepancy there in terms of long-term fiscal solvency, as measured by the independent bond rating agencies.

Ratings agencies classify investment-grade debt (debt which is allowed to be held by conservative investors like pension funds) on a 10-point scale. Anything below the lowest point on that ten-point scale (BBB- using Standard & Poor’s terminology) is “junk” (non-investment-grade). As of this week, 15 states had the highest possible AAA rating. Only four states scored in the bottom half of the investment-grade ratings, with one state conspicuously worse than all the others.

| S&P Credit Ratings for States – as of April 20, 2020 |

| AAA |

15 |

DE, FL, GA, IA, IN, MD, MN, MO, NC, NE, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA |

| AA+ |

12 |

HI, ID, MA, ND, NV, NY, OH, OR, SC, VT, WA, WY |

| AA |

13 |

AL, AR, AZ, CO, ME, MI, MS, MT, NH, NM, OK, RI, WI |

| AA- |

5 |

AK, CA, KS, LA, WV |

| A+ |

1 |

PA |

| A |

2 |

CT, KY |

| A- |

1 |

NJ |

| BBB+ |

0 |

|

| BBB |

0 |

|

| BBB- |

1 |

IL |

Republicans are starting to make a “moral hazard” argument here (as spelled out in this Wall Street Journal editorial) – that the federal government should not reward decades of fiscally irresponsible decisionmaking by certain states. This is akin to the difficulty faced by the government when providing financial assistance to a company like Boeing – how to provide aid to ameliorate problems that are clearly not the company’s fault (the catastrophic drop in the demand for airplanes caused by coronavirus) while, at the same time, not bailing them out for a pre-COVID problem that clearly was the company’s doing (the 737 MAX problem).

The WSJ singles out Illinois (as do the bond-rating agencies), where the President of the State Senate has requested a $44 billion bailout from Congress, including $10 billion just for pensions. The persistent unwillingness of many state and local governments to adequately put money aside to fund long-term pension obligations is the biggest single obstacle to financial stability in many states. And it’s the pension problem that adds an extra element of politics to the discussion, because the labor unions that represent the state and local government employees who will someday rely on those underfunded pensions are one of the most important components of the Democratic Party’s financial and get-out-the-vote infrastructure. It has become a vicious cycle – public employee unions campaign for Democrats, which infuriates Republicans into taking more legislative positions against the interests of the unions, which makes the unions campaign even harder against Republicans in the next election.

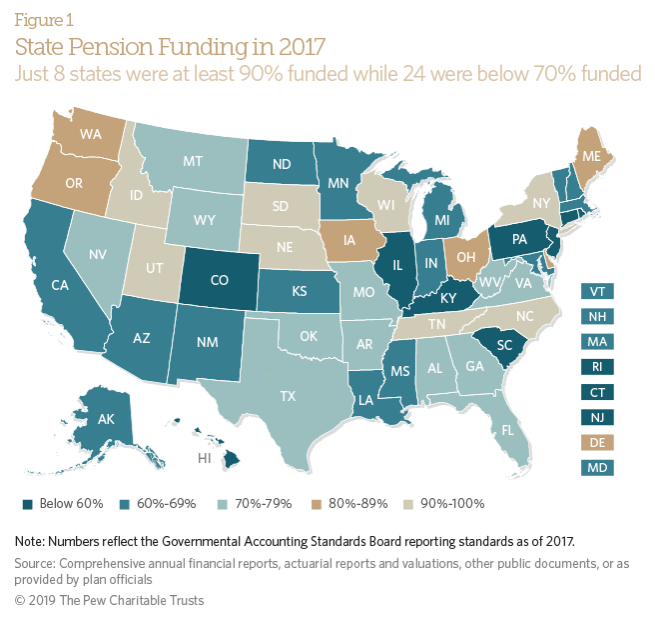

In this regard, it was a bit jarring to see Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) suggest that, as an alternative to direct financial aid, a provision in law be made to allow state governments to declare bankruptcy. (Not that the argument doesn’t have some intellectual merit, but note how the Bluegrass State is in the bottom four states in terms of credit ratings, right there with ultra-blue Connecticut and New Jersey.) A 2019 report from the Pew Charitable Trusts noted “Kentucky, New Jersey, and Illinois have the worst-funded retirement systems in the nation in part because policymakers did not consistently set aside the amount their own actuaries said was necessary to cover the cost of promised benefits to retirees.”

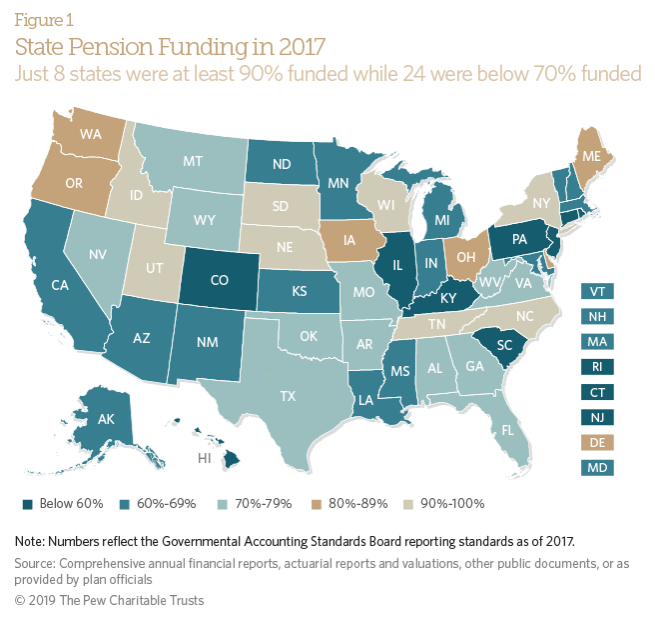

The problem is not entirely red states versus blue states – per the Pew report: “Overall in 2017, states had 69 percent of the assets they needed to fully fund their pension liabilities—ranging from 34 percent in Kentucky to 103 percent in Wisconsin. In addition to Kentucky, four other states—Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, and New Jersey—were less than 50 percent funded, and another 15 had less than two-thirds of the assets they needed to pay their pension obligations. Only Idaho, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Utah joined Wisconsin in being at least 90 percent funded (Figure 1).”

If the federal government is going to get into the business of providing states with pension relief, even temporarily, how on earth do you structure a program providing that relief that is fair to the taxpayers of Wisconsin (the only state with a completely funded pension program as of 2017) and still takes care of Kentucky, which only had 34 percent of its pension costs covered? More generally, should a state that has been thrifty for a long time and earned an AAA credit rating be given financial assistance on the same terms as a state that has slouched its way into a BBB- rating?

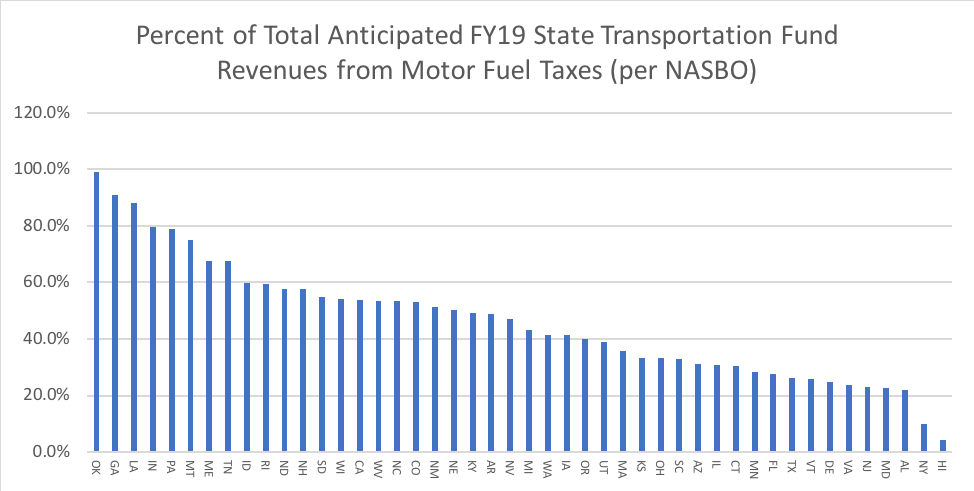

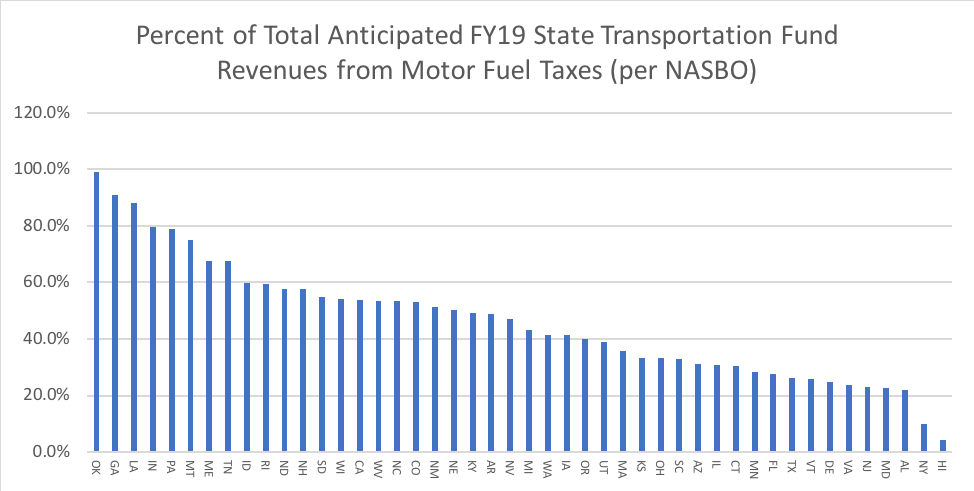

The potential for these overall state issues to drag down any future legislation means that state DOTs may be more likely to get their own dedicated aid from Congress, such as mass transit agencies and airports received in the phase 3 legislation. But there are issues with that as well – it’s one thing for states to ask the federal government to replace revenues lost to coronavirus, but actually putting a dollar amount on each state’s loss is difficult, because these laboratories of democracy get their transportation funding from many different revenue sources, and some of those are much more affected by coronavirus than others.

Minnesota in particular gets an inordinately high share of its annual highway and transit budget from the sale of motor vehicles. And the drop in car sales is undoubtedly much worse than the drop in gasoline sales. Gasoline production at the refinery or blending facility has stabilized at around 60 percent of the pre-COVID level, and we have had enough time for decisions at the pump to make their way fully upstream to the refiner/blender level, so that 40 percent reduction is probably the new normal. But total motor vehicle sales in the U.S., per the St. Louis Fed, went from a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 17.35 million per year in January 2020 down to 11.66 million in March 2020 (a reduction of 33 percent) – and things were going pretty much as normal in the first half of March. One can only imagine how much worse the April number will be.

Contrast that to the Great Recession, where a December 2007 peak of 16.03 million vehicles per year declined to a pace of 6.81 million vehicles per year, a reduction of 42 percent – but that took 14 months (the bottom was February 2009). The three-month drop from January to April 2020 will almost certainly be much worse than 42 percent. (This author is planning on testing the market next week to see just how many ridiculous incentives local dealers will throw at him to try and convince him to buy a new car.)

Per NASBO, Minnesota gets about 28 percent of its state transportation fund dollars from motor fuel taxes, and if those really have been reduced by 40 percent, that is about an 11 percent cut in total state transportation revenues on a monthly basis. But Minnesota was going to get about 27 percent of its state transportation revenues from car sales, and a hypothetical 80 percent reduction in those would cuts its total state transportation revenues by an additional 21 percent. (Missouri also gets a lot of its transportation money from dedicated car sales.)

Motor fuel taxes have long been prized for their low volatility. Even in a national lockdown, gasoline is only off 40 percent, and diesel is almost certainly off by much less than that (refiner-level data lumps highway diesel in with rail diesel and home heating oil so we can’t tell total highway diesel production from their numbers). Drivers license and vehicle registration renewals are probably the least volatile revenue source (if there aren’t significant delays in renewals caused by the shutdown of physical state DMV offices).

Per table A-5 in the NASBO report, Oklahoma derives 99 percent of its state transportation fund from cent-per-gallon motor fuel taxes. On the other end of the spectrum, Hawaii only gets 10 percent of its transportation fund from this source. (Upstream petroleum taxes are not counted as motor fuel taxes in the NASBO report, and there are some other holes in that dataset, such as a few missing states.)

Can the federal government really use a one-size-fits-all assumption for the amount of dedicated transportation revenues that each state DOT is losing or will lose during the COVID crisis? Or would federal revenue replacement grants have to be tailored to each state’s individual needs, with the states that have placed greater reliance on more volatile revenue sources getting more money?

A related question is: should the federal government volunteer to replace hypothetical new revenue sources that were in state budgets but might not have been realized, even if coronavirus had never reached U.S. shores? The New York City congestion pricing plan springs to mind, which was going to raise a lot of money for the state government (mostly transferred to the MTA) during fiscal year 2021, as already enacted in the 2020 budget. This was already delayed for reasons having nothing to do with coronavirus (foot-dragging by the Trump Administration on tolling permissions and reluctance by local officials to set detailed rules and exemptions). Should the federal government replace that hypothetical revenue anyway?