October 20, 2017

Over two dozen states have now passed legislation or issued executive orders to regulate the development of automated vehicle (AV) technology. While the policy approaches of each state have become increasingly diverse from year to year, they all descend from two common ancestors: Nevada and California.

Ten years ago, AVs had all the appearance of a pipe dream. Self-driving technology was a hobby for amateur roboticists, a dream for academics, and a crowd-sourced experiment for the military.

AVs might have remained as a utopian dream, if it weren’t for the exponential increases in computing power and, consequently, Google’s high-profile investments in mapping and self-driving cars. These factors galvanized the tech and automotive sectors to race towards developing fully autonomous vehicles.

But state laws did not keep pace with the tech sector’s new fascination. In fact, policymakers did not even consider that a human might not be driving a car at all. The result was a Wild West era for AVs where the private sector tested AVs without significant oversight from authorities.

When the first AV laws were enacted in Nevada (2011) and California (2012), they set a precedent for how the nascent technology would be regulated from coast-to-coast and at all levels of government. They emphasized collaboration and communication between the private sector and government officials, rather than prescriptive regulations and government mandates.

For the most part, this model inspired the next 19 states and Washington, D.C. when they wrote their own AV laws. In fact, a handful of states even copied California’s laws nearly word-for-word.

This first wave of AV laws presumed (if not required) that the vehicles would still have a human behind the wheel, since the technology and public opinion had not yet developed to the point of being fully autonomous – the point where humans could be fully removed from the driving equation.

For example: when the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) adopted its first AV testing regulations in 2014, it required a human to be in the driver seat and capable of immediately taking control of the vehicle.

But now, as the technology is reaching maturity and capturing the public imagination, states are beginning to evaluate the second wave of AV regulations that will allow for the operation of truly driverless vehicles – and once again, California is leading the charge with a comprehensive set of regulations around how this technology will be operated on its roads.

Let’s Try This Again…

On March 10, 2017, the California DMV released its first set of proposed regulations for the testing and deployment of fully autonomous vehicles – including those without anyone in the driver seat at all.

A 45-day public comment and workshop period followed the release, during which auto manufacturers and tech firms railed against what they saw as overly burdensome regulations on deployment and development. The DMV then used these comments to revise the regulations and build a consensus through further conversations with stakeholders.

The DMV released a revision to its proposed regulations for testing and deploying driverless vehicles on October 11. It aims to strike the delicate balance between meeting manufacturers’ requests for permissive regulations and ensuring that driverless vehicles are tested responsibly.

The proposed regulations try to avoid overstepping the extent of the state government’s authority. While states handle numerous issues pertaining to motor vehicles such as traffic laws and driver licensing, the federal government retains express authority to set the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) that regulate the design, construction, and performance of the vehicle itself.

This is especially important, as Congress is currently considering legislation that would preempt state laws that attempt to regulate the design, construction, and performance of AVs. The House passed the SELF DRIVE Act (H.R. 3388) unanimously in September and the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee approved AV START (S. 1885) earlier this month. Among the significant differences in those bills that must be resolved is the preemption language contained in each. (ETW subscribers can access a full side-by-side comparison of the bills here.)

As such, the state cannot place stringent requirements on the sensors, software, hardware, or physical components of the vehicle. Instead, California seeks to establish a set of rules for when, where, and how driverless vehicles are tested in its borders by:

- establishing a process for manufacturers to obtain testing permits;

- requiring manufacturers to submit annual reports about their vehicle miles travelled (VMT), disengagements of the automated system, and collisions; and

- creating a clear set of rules and expectations for manufacturers to follow throughout the testing phase.

This approach falls in line with the federal AV policy statement that was recently updated by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). The document, titled Automated Driving Systems: A Vision for Safety 2.0, clearly delineated the respective roles of federal, state, and local governments in overseeing the safe testing and deployment of AVs.

Following the release of the proposed regulations, the DMV opened up a 15-day public comment period that will end on October 25. Afterwards, the rules are expected to be submitted to the state government for approval to be enacted and enforced by the middle of 2018.

(Note: The following is an analysis of the proposed regulations for testing driverless vehicles in California. An analysis of the regulations for deploying driverless vehicles will follow in future editions.)

Covering the Basics

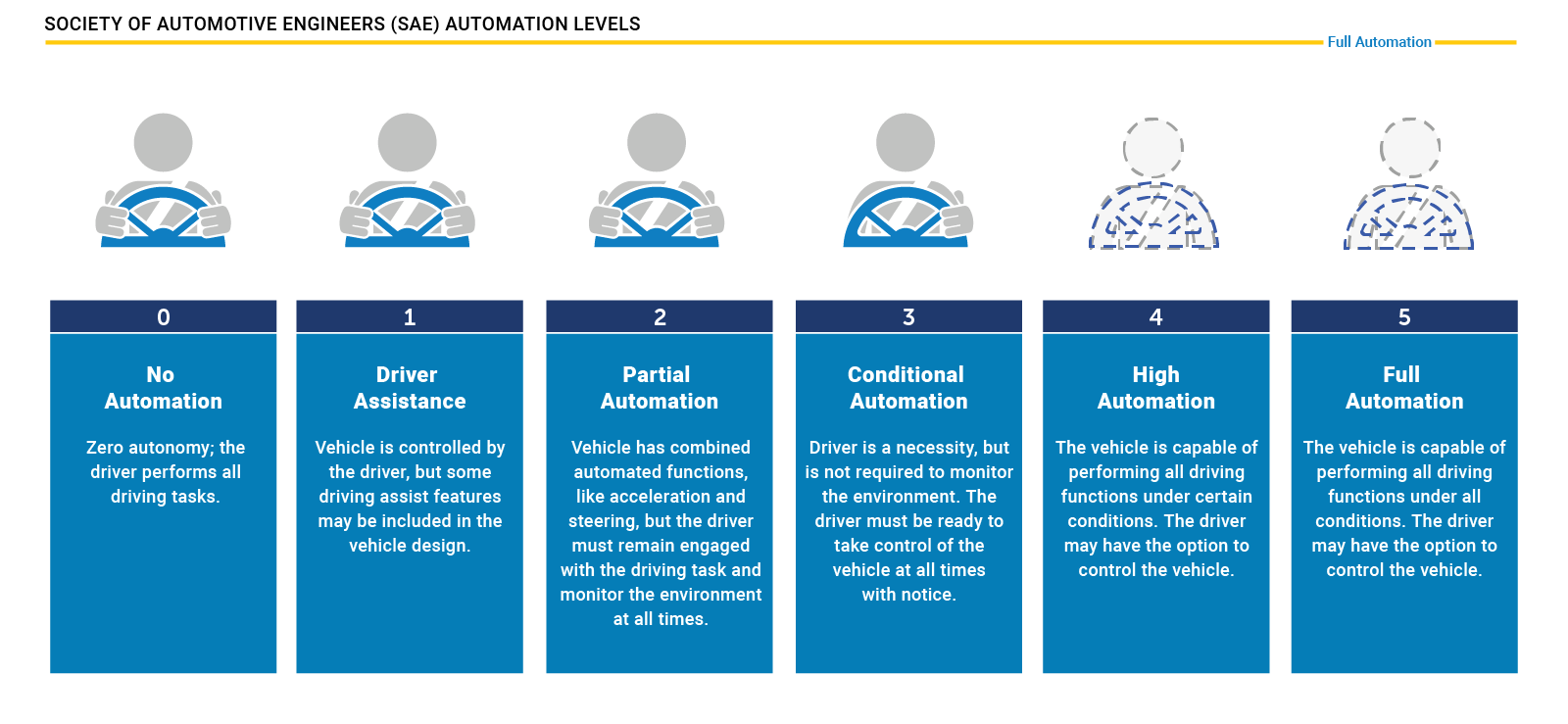

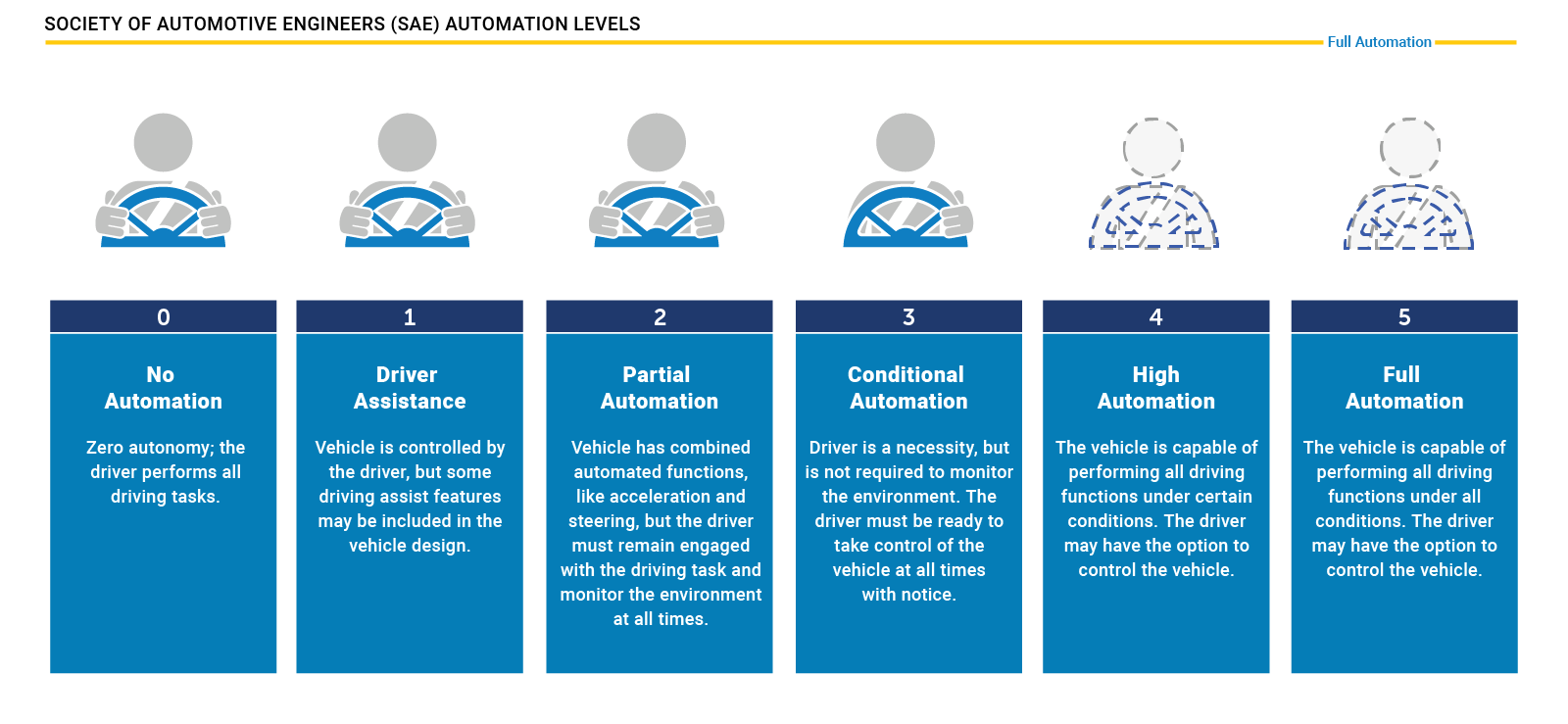

These regulations will utilize the taxonomy and definitions developed by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) International in the SAE J3016 standard for automated driving systems. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), auto manufacturers, many state governments, and others have adopted these definitions to ensure consistency in how the technology is regulated and publicly discussed.

Accordingly, California’s regulations on driverless vehicle testing pertain to vehicles equipped with automated driving systems capable of operating at levels 4 and 5 (hereafter referred to as AV4 and AV5).

An AV4 can operate without human intervention within its ODD. That ODD could be as small as one city street on a sunny day. It can also be as large (or larger) than an entire state under any weather conditions.

An AV5, meanwhile, could operate entirely without human intervention anywhere, regardless of weather conditions, type of road, time of day, geography, or urban/rural environment.

And while California is the leading state for AV testing, the state has taken a decisively negative stance toward testing automated trucks in its borders: the proposed regulations expressly forbid entities from testing automated systems for trucks or motorcycles. This is in spite of the fact that some of the companies that call California home, such as Uber and Tesla, are actively developing AVs and testing them in nearby states.

However, the issue is not unique to California. In developing what may become the first federal laws around AVs, both chambers of Congress opted to not include automated trucks in their bills due to concerns about worker displacement and public safety.

Phase 2: Driverless Testing

The first wave of AV policies all shared a common interest in reducing regulatory uncertainty for manufacturers testing vehicles that would still be overseen by a human operator.

From a birds-eye view, this was a relatively straightforward task – states could require manufacturers to register their AVs and drivers, set AV insurance minimums, establish reporting requirements, and experiment with innovative policies like a road-use fee for AVs.

But when a human operator is no longer physically present and capable of taking over control of the vehicle, many more questions arise for law enforcement, first responders, insurers and legal professionals, a potentially skeptical public, and the manufacturers themselves.

For this reason, the California DMV will create a second class of AV testing permits for driverless vehicles that is wholly separate from the existing AV testing permits.

In order to obtain a driverless testing permit, the manufacturer must submit an application (see form OL 318) to the California DMV. An official from that manufacturer must sign off on nearly two dozen topics to certify that the vehicle is capable of safe operation, that the manufacturer is actively engaging with government officials, and that the manufacturer will take responsibility for its actions.

The following is an overview of the important points within the application and their implications.

Safety Assessment Letter

The previous version of the proposed regulations would have required manufacturers to submit a Safety Assessment Letter (SAL) to the DMV. The SAL, as it was defined in Federal Automated Vehicle Policy Statement (FAVP), was a voluntary document that manufacturers could submit to NHTSA that described how their automated system worked.

However, another section of the FAVP provided state governments with best practices for AV-related policymaking. There was a significant amount of confusion around one key part of this guidance, which appeared to recommend that states could require manufacturers to submit an SAL – even though NHTSA intended for it to be voluntary.

However, last month’s revision to the FAVP, now titled “Automated Driving Systems 2.0: A Vision for Safety,” removed the SAL entirely. In the document, NHTSA stated that manufacturers can choose to submit the Voluntary Safety Self-Assessment (VSSA) and discouraged states from requiring it to be submitted.

As a result, the latest revision to California’s proposed AV regulations instead requires manufacturers to submit the VSSA to the DMV only if they have already publicly disclosed an assessment of their approach to AV safety (this would be the case for Waymo, which recently published a description of its safety approach online).

Remote Operators

During driverless testing, the manufacturer must ensure that there is someone (metaphorically) behind the wheel.

This means that each vehicle must have a remote operator who is capable of taking back control in case of an emergency. This person must be trained by the manufacturer in how to control the system overall, and also how to handle emergency situations.

For example: if Waymo is testing a driverless vehicle in San Francisco, it must have one dedicated person sitting at a computer (whether at Google HQ in Mountain View or somewhere else) who is monitoring its performance and is trained to take control if the vehicle encounters a hazard that it is not capable of dealing with.

Defining Operational Design Domain (ODD)

Prior to applying for a permit, the manufacturer must certify that the driverless vehicle has been tested under controlled conditions that simulate the situations and locations in which it is designed to operate.

This designation is known as the operational design domain (ODD), which can include time of day, geography, type of road (e.g., city street, freeway), urban or rural settings, traffic conditions, and any other factors that may influence the system’s ability to drive.

SAE Level

When submitting their application, a manufacturer must certify that their vehicle is capable of operating at AV4 or AV5 without the physical presence of a human driver.

When a manufacturer has certified that their autonomous system has reached level 5 driving autonomy, they can inform the DMV in order to have their designation updated.

This is a short section, but has significant impacts: AV levels 4 and 5 are next to one another on the scale of autonomy, but are nevertheless worlds apart. As discussed above, an AV4 is capable of fully driving itself within its ODD, while an AV5 is capable of driving itself in every situation.

Liability

The manufacturer must certify that it will assume liability for damages caused by its driverless AV when the autonomous technology causes a collision and is found to be at-fault.

This section was revised since the proposed regulations in March, which said that manufacturers would assume “any and all responsibility” in any collision associated with operation of the vehicle on public roads, to the extent that the vehicle is at-fault.

Informing Local Authorities

Before testing a driverless vehicle in any jurisdiction, manufacturers must first submit details of the vehicle and testing procedures to local authorities (defined under California VEH § 385 as the legislative body of any county or municipality having authority to adopt local police regulations).

This will include the following:

- Test vehicle ODD

- A list of all public roads where vehicles will be tested

- Days and times that testing will be conducted

- The number and types of vehicles that will be tested

- Contact information for manufacturer conducting the testing

Law Enforcement Interaction

If a manufacturer’s permit is accepted, they must email a law enforcement interaction plan to the California Highway Patrol (CHP) within 10 days. It describes the vehicle’s ODD, how law enforcement can communicate with remote operators of driverless AVs when no one is in the vehicle, how to verify whether the automated system is activated, and how to interact with the vehicle in a potentially hazardous situation (e.g., after a collision).

This plan will be updated at least annually. It must also be posted online and shared with law enforcement and first responders within the ODD where the vehicle will be tested.

Administration of Permits

California’s success in becoming the leading state for AV developers has been a boon for its reputation as the nation’s tech hub, but it has come with a price.

The California DMV administers the largest AV testing program of any state, clocking in at 42 registered manufacturers when this article was published. This has proven to be a costly endeavor for the DMV, which led the department to propose raising its application fee for AV testing permits from $150 to $3,600 per manufacturer for a non-driverless or driverless permit.

Application Reviews

The DMV will be required to review applications for manufacturer’s testing permits within 10 days of receipt and inform the applicant if their application is complete or incomplete.

If the application sufficiently explains its technology and meets all of the testing requirements, the DMV will approve it and issue a permit to the manufacturer. Permits are valid for two years, and manufacturers must submit a new application form to renew.

However, if an application is not complete, the DMV will notify the manufacturer of deficiencies and allow the manufacturer a “reasonable period of time” to correct it. This may be as simple as providing additional proof of insurance, but it could also require a revamp of the technology that is used to control the vehicle remotely.

If a deficiency is not corrected in that “reasonable period of time,” the application will be rejected.

Suspensions and Revocations

If a manufacturer is found to be acting in bad faith or violating the state’s AV regulations, the DMV will send the manufacturer a 15-day written notice before suspending or revoking their permit. Grounds for suspension or revocation could include: not maintaining financial responsibility (e.g., insurance, surety bond, self-insurance), omitting information about the AV that poses an unreasonable risk to the public, or operating the vehicle outside of its ODD.

However, if a manufacturer’s testing operations are found to be unsafe for public roads, the department has the authority to immediately suspend their permit for driverless testing.

Suspensions and revocations will remain in effect until the department is able to verify that the manufacturer has rectified the issue and restores the permit.

Manufacturers can contest a decision by the DMV to now issue or renew a testing permit by demanding a hearing before the department within 60 days of notice of the refusal.

Keeping the Wires Hot

After receiving a testing permit, manufacturers would effectively be required to be in regular contact with the DMV about updates to their technology, expansions of the vehicle’s ODD, and new testing dates/times. Whenever any of these change, manufacturers have to submit an updated OL 318 (the driverless AV testing permit) with a payment of $70.

Similarly, the manufacturer must send local authorities any new information about updates of the vehicle’s ODD, law enforcement plans, and newly scheduled testing dates/times.

This means that the DMV and local authorities will always be aware of the vehicles being tested across the state.

This also means manufacturers would not be able to spontaneously test their technology which, in practice, could be a challenge for those who want to test their technology in a variety of weather conditions.

Reporting Requirements

Similar to California’s existing AV testing requirements, manufacturers are required to submit reports for any collision involving their driverless AV. This report must include details of the entities involved, observations of any property damage or bodily harm, and a description of the incident.

Additionally, manufacturers are required to retain data about disengagements of the automated system by the human operating the vehicle (whether they are physically present or supervising the vehicle remotely). This data must describe the circumstances leading to the vehicle being disengaged and is to be submitted to the DMV in an annual report using a standard form.