Alan Stephenson Boyd, the first U.S. Secretary of Transportation, died on Sunday, October 18 at his assisted living facility in Seattle, at the age of 98. His son Mark reported that there was no specific illness, only the gradual and peaceful shutdown of the human body at a ripe old age.

Boyd led an interesting life. I was a volunteer fact-checker for his self-published memoir released in 2016 (which I reviewed here), which starts with the fact that Boyd may have been destined for a life in transportation (his father was a highway engineer, his stepfather was a railroad lawyer, and his mother’s grandfather was the inventor of the streetcar). His upbringing was split between his parents’ home in rural Florida and the better schools that his mother would sometimes send him to with her Stephenson relatives in New York or Boston for a semester at at time.

His initial aimlessness was ended by World War II, where he flew C-47 transports for the Army Air Corps, dropping paratroopers over Normandy and Arnhem, dropping supplies over Bastogne in the Battle of the Bulge, and performing other transport duties. He was recalled for active service in Korea as well.

After getting a postwar law degree from the University of Virginia (he somehow talked himself into law school despite never having finished his undergraduate degree), he took a job at a law firm in Miami where one of the name partners was George Smathers. When Smathers successfully ran for Senate, Boyd was roped into politics, and later worked on a gubernatorial campaign that resulted in a political appointment as as staffer for the Florida Turnpike Commission. This led to an interim appointment as member of the Florida railroad commission, and in order to keep the seat, Boyd had to run in a statewide election, which he did, successfully.

His state service led to a decade of federal service (described in detail below), after which Boyd ran a freight railroad (the Illinois Central, from 1970-1976) and a passenger railroad (Amtrak, from 1978-1982), ran a brief side business during his Amtrak tenure trying to build a true high-speed rail line between Los Angeles and San Diego (American High Speed Rail Corporation), and ran an aerospace manufacturer (Airbus Industrie North America, from 1982-1992) before retiring.

But let’s just look at his decade of federal service (plus a bonus few months in 1977).

Civil Aeronautics Board. Boyd’s transition from Florida politics to the national scene came about because of his old mentor Smathers and the other Florida Senator, Spessard Holland (D). In 1959, one of the Democratic seats on the Civil Aeronautics Board had come open, and Smathers and Holland wanted to put Boyd’s name forward to fill the seat. Although President Eisenhower, by law, had to appoint a Democrat, he had to approve the individual, so Boyd went to the White House to meet with Chief of Staff Wilton Persons. At the end of their conversation, Persons asked Boyd if he believed in private enterprise, to which an astonished Boyd responded, “not only do I believe in private enterprise, but I am a firm believer in the profit motive.” Eisenhower nominated Boyd, and the Senate swiftly confirmed him.

Once John F. Kennedy replaced Eisenhower, Kennedy designated Boyd as chairman of the CAB. As chairman, one of Boyd’s biggest priorities was trying to overcome the inherent financial disadvantage faced by U.S. carriers on international routes under many of the existing bilateral aviation agreements. At that time, almost every country had a government-owned national airline that flew all of its international routes. When the government owns the airline, receipts from airfares go into the government’s pocket, just like taxes. But the U.S. had no government-owned airline, instead using private companies like Pan Am and TWA to carry its international traffic.

As Boyd wrote in his memoir, “Many countries would have been happy to let U.S. carriers fly in and out of their airports without limitation. The caveat, however, was that they wanted fifty percent of all the revenues generated on those routes—regardless of which airline generated it. The U.S. carriers, as private businesses, of course, needed to keep their profits.”

At the time, international airfares were set by IATA conferences (which aviation guru Jeff Shane called “legally immunized cartels”). When the IATA conference voted to increase transatlantic fares in 1962 (instead of lowering them to reflect decreased operating costs as jets replaced prop planes, as Boyd wanted), Boyd and the CAB rejected the higher fares, creating a one-sided transatlantic fare war. (Boyd wrote that “When a Pan American flight landed in Stockholm, the Swedish government required every passenger to pay the difference between the lower Pan Am airfare and the IATA rate before allowing them to get off the plane.”)

Emergency meetings held in London between major nations were attended by Boyd, who gave daily press conferences asking why European leaders refused to pass on aviation cost savings to their citizens. This got to the point that Prime Minister Harold Macmillan called President Kennedy to complain about Boyd, leading to Boyd being recalled to Washington, hauled into the Oval Office and chastised by JFK. Boyd was forced to accept the higher IATA fares in exchange for IATA moving up the next scheduled fare-setting meeting.

Economic regulation was only part of the CAB’s job. They also set safety regulations and investigated accidents. And this part of the job may have led to Boyd’s subsequent federal posts. On February 19, 1961, a private jet owned by Lyndon Johnson (actually, it was in his wife’s name) inbound from Austin crashed at the LBJ ranch in low-visibility weather while trying to find the runway. The plane was empty except for the two pilots, both of whom were killed.

It was Boyd’s turn in the rotation to go investigate the crash, and as the CAB point man, Vice President Johnson telephoned Boyd almost every single morning during the duration of the accident investigation to ask for the latest details. Boyd later said that LBJ’s concern appeared to be making sure that the families of the pilots got their insurance payout, and that Johnson never overtly tried to influence the investigation. But that daily contact apparently put Boyd in good stead with Johnson, which would pay off later.

Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation. Boyd eventually tired of the CAB and notified the White House in spring 1965 that he was not going to seek another six-year term. Unbeknownst to Boyd, Clarence Martin was preparing to leave his job as Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation. On April 27, 1965, a White House staffer called Boyd to the White House and would not tell him why. Boyd was then shuffled into the East Room and given a front row seat at the President’s press conference.

Unbeknownst to Boyd, Johnson then announced that he was nominating Boyd to be Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation. Boyd accepted the nomination and was quickly confirmed by the Senate. Much of his tenure there was spent on a quixotic campaign to get rid of U.S. shipbuilding subsidies and U.S.-flag merchant marine operating subsidies, which went precisely nowhere on Capitol Hill.

Other of Boyd’s priorities while Under Secretary included:

- Highway beautification – This was Lady Bird Johnson’s big priority, and Boyd had to help move the bill through Congress. Members of the Public Works Committees were extremely resistant to giving Highway Trust Fund money for beautification (see White House documents here). Boyd’s memoir tells of Johnson telling Boyd to go to the Hill and order Senate Highway Subcommittee chairman Jennings Randolph (D-WV) to fund the program (Boyd wrote “I don’t know what the President had on Jennings, but Jennings knew that he had no choice.”). Randolph agreed to amend the bill on the morning of September 16, 1965, to penalize states that did not comply with the beautification law by cutting their highway funding, and as Randolph did so, Boyd was in the gallery, and later wrote “Jennings looked directly at me. It is the only time in my life I’ve seen pure hatred in another’s eyes. After that, Jennings never spoke to me again.” The Beautification Act became law the following month.

- Motor vehicle safety standards – The Johnson Administration, through Commerce, proposed the first real motor vehicle safety legislation in 1966, and the twin bills creating a highway safety bureau and a motor vehicle safety bureau, both under Commerce, were enacted on the same day in September 1966. Boyd wasted no time in proposing significant new safety standards. Boyd tells in his memoir of Henry Ford II coming to see him and saying “I’m here to say that you can forget about that damn seatbelt rule, Boyd. It’s not going anywhere. Nobody wants it and you’re wasting your time. Besides, seatbelts don’t do a bit of good.” Boyd (and the first administrator of the twin safety agencies, Charles Haddon) persevered. The first Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards including a seat belt mandate, were promulgated on November 30, 1966 in draft form under Boyd’s signature (see p. 15212 here) and became final in February 1967.

As Under Secretary for Transportation, Boyd was the Commerce point man for the discussions on spinning off Boyd’s portion of Commerce into a separate Department of Transportation. Eno has a complete documentary history of this whole endeavor, but in summer 1965, Boyd co-chaired (along with a senior Bureau of the Budget official) an internal task force that recommended a series of transportation policies to be introduced in 1966, including the creation of a Cabinet-level Department of Transportation. President Johnson signed a preliminary approval document in September 1965, and Boyd had to fend off last-minute opposition from the FAA, but LBJ transmitted the plan to Congress (including the draft bill written by Boyd’s task force) in March 1966.

(As part of his outreach in support of the proposal, Boyd even wrote an article for Eno’s Traffic Quarterly publication for the July 1966 issue.) Boyd testified at the Senate hearings and the House hearings, and while much of the Johnson Administration’s relations with Congress were handled by the White House (because LBJ was LBJ), Boyd also handled a good deal of it. In fact, Boyd blames himself for one of the big difficulties faced by the proposal on Capitol Hill.

Boyd’s one-man war against maritime subsidies in 1965-1966 had earned him the enmity of the powerful maritime unions, and with Boyd being the senior Johnson Administration transportation official and the public face of the proposal to create a Cabinet-level DOT, which would include the Maritime Administration, there was a lot of speculation that Boyd would become the first Secretary of Transportation if the bill was enacted into law. Boyd wrote in his memoir that “The ship owners and the seaman unions never forgot that I’d tried to end their subsidies. There was a possibility that I’d be named as the DOT’s first Secretary, since I was the senior federal official for transportation. The maritime industry used its influence at the committee level to remove the Maritime Administration from the Department, and therefore from any possibility of being under my control.” MARAD would eventually be transferred from Commerce to DOT – in 1983.

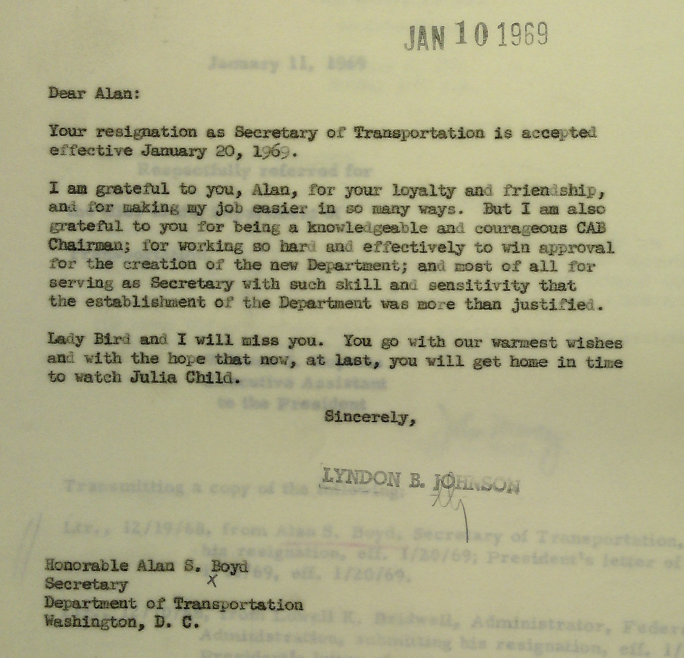

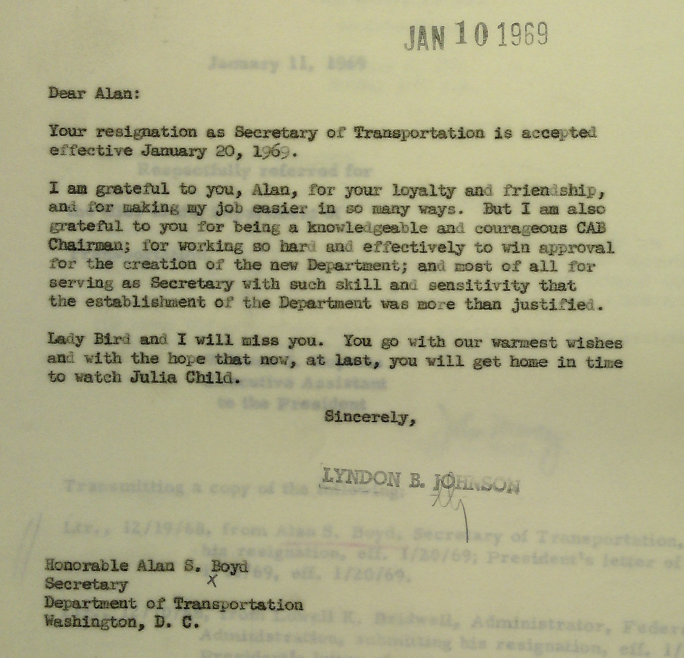

Secretary of Transportation. The DOT bill was signed into law on October 15, 1966, and the new Department was to take effect after a transition period (later determined to be April 1, 1966). Boyd was presumed to be the front-runner for the Secretary job – this telephone call between LBJ and Boyd, the day the bill was signed, indicates confusion as to whether Boyd wanted that job, or (as had been reported in the New York Times) a job running the Association for American Railroads instead. Johnson invited Boyd down to the LBJ Ranch a few days later and formally offered him the job as Secretary, and he was confirmed in mid-January 1967, giving him two-and-a-half months to organize the department and hit the ground running.

Boyd, in his capacity running the task force and then as Secretary, set up the initial organization of the Department. The law let Boyd assign responsibilities to four Assistant Secretaries as he saw fit. Rather than give the Assistant Secretaries modal responsibilities, he gave them “cross-cutting” jobs. The first three were Public Affairs, Research and Technology, and Policy Development. For the fourth, Boyd wanted Urban Affairs, as Boyd later said in an oral history interview, “feeling quite rightly that this was going to be the area of greatest concern and greatest impact. And also realizing the there was no good coordinating mechanism short of the Secretary for relationships between highways, mass transit, and airports, and airport access, and things of that nature.” However: “…after we kicked that around for quite a while, we decided we couldn’t afford to do that because it would be presumptuous as all hell in view of the fact that the urban mass transit was over in HUD, and we were gearing up to take it away from them…I came to the conclusion, supported by the task force advisers, that it just would be very poor taste to try to do that at this stage of the game.” The fourth job was instead created as International Affairs.

The law created within DOT a new Federal Highway Administration and a new Federal Railroad Administration. As originally spun up, FHWA comprised the Bureau of Public Roads, as well as the new highway safety bureau and the new vehicle safety bureau. Before long, the highway safety and vehicle safety bureaus were taken out from under FHWA and merged into a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reporting directly to the Secretary.

There were problems integrating Public Roads into the new Department (which had been formed, in part, to keep Public Roads from dominating other modes), but they paled in comparison to integrating the FAA. After years under the Commerce Department as the Civil Aeronautics Administration, the FAA had been created in 1958 as an independent federal agency answering directly to the President, and to be put back into a Department again nine years later, answering to a Cabinet Secretary once again, was humiliating. The fact that the new DOT did not have its own building, and Boyd and his staff were forced to camp out in the FAA headquarters building at the beginning, was also uncomfortable.

On the bright side, as Boyd wrote, “While the FAA felt like it’d been put in prison, the Coast Guard, transferred from the Treasury Department, felt like it’d been paroled.” No one from the Coast Guard felt they had any potential for advancement at Treasury, but Boyd made sure to include Coast Guard personnel in a variety of policy and administrative jobs throughout DOT.

When chairing the task force, Boyd was a strong advocate for taking responsibility for mass transit away from HUD and giving it to DOT, (see this article for details), but the eventual compromise was for a one-year joint DOT-HUD study of the issue, to be resolved in 1968. This ETW article details how Boyd and his staff outmaneuvered HUD and convinced President Johnson to move transit to DOT by May 1968, uniting all modes (except maritime) in one place.

When it came to transportation policy, Boyd’s tenure as SecDOT unfortunately coincided with the tailspin of the entire Johnson Administration agenda, as the Vietnam War gradually sucked all of the oxygen out of the White House (as Boyd relates in his memoir). Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election in 1968 was a surprise to almost everyone in his Administration when he announced it on March 31, 1968.

And the policy that Boyd discusses most in his memoir from his time as SecDOT was the ill-fated SST (the American attempt to build a supersonic passenger airliner to compete with the Concorde being built by Europe). After over a decade, and billions of dollars spent, Congress killed the SST in early 1971 because of noise complaints about the potential sonic booms.

As Secretary, Boyd inherited responsibility for signing off on the highway funding cutbacks that had been ordered starting in fall 1966 by the Bureau of the Budget as both a budget-balancing and an anti-inflation measure. Files in the LBJ Library (which we will get around to digitizing eventually) reveal that Boyd fought with BOB behind the scenes about the implementation and duration of those cutbacks.

Those cutbacks were administrative. The only highway legislation passed during Boyd’s tenure at DOT was the 1968 Highway Act, which Johnson almost vetoed because the bill ordered USDOT to complete the planned Interstate expressways running across the District of Columbia, including construction of the proposed Three Sisters Bridge. (See the White House enrolled bill file for details.) However, the 1968 bill did provide for an additional 1,500 miles of Interstate mileage, to be doled out by DOT. Boyd and his team worked as quickly as possible to designate as much of that mileage before leaving office.

Interestingly, Boyd’s biggest successes at changing transportation policy via legislation may have come after he left office. As mentioned above, Lyndon Johnson’s decision to pull out of his 1968 re-election race was a surprise, and definitely put a damper on the rest of the legislative agenda for 1968 and beyond. But Boyd’s policy team was still working on several proposals, two of which were later picked up by the Nixon Administration (under Transportation Secretary John Volpe), tweaked a bit, and resubmitted to Congress in 1969, to become law in 1970:

- Airport and airway financing – Boyd had submitted a bill to Congress in May 1968 to increase aviation excise taxes, as “user charges,” to pay for increased air traffic control expenses. Congress did not go along with the plan in 1968 (see these White House memos for how that went), but Nixon then sent a modified version of the bill to Congress in June 1969, which later became the Airport and Airway Development Act of 1970, creating the Airport and Airway Trust Fund that is still in use today.

- Mass transit – On his way out the door, so to speak, Boyd proposed a mass transit reauthorization bill in December 1968 that would have provided for a fivefold increase in annual mass transit spending, paid for by an increase in the existing excise tax on new cars, to be deposited in a new Urban Transportation Trust Fund. This became the basis for bills introduced in Congress by Democrats in early 1969, and after much internal debate (described in this article, “The Johnson-Nixon Mass Transit Bill of 1968-1969”), and dropping the trust fund idea at the last minute, a version of it became Nixon’s proposal in August 1969. A modified version was signed into law as the Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act of 1970. (That law provided the first really significant funding for mass transit – program obligations went from $110 million in fiscal 1970 to $989 million in fiscal 1973 due to the funding provided in the 1970 law, as proposed by Boyd in 1968.)

Ambassador for US-UK aviation talks. In 1946, the United States and the United Kingdom negotiated and signed a bilateral aviation agreement in Bermuda. In June 1976, the British government served notice to the United States that they were activating the one-year severance clause of the Bermuda agreement, meaning that the agreement would cease to have effect at midnight on June 21, 1977. This also meant that no more direct flights between the US and the UK could take place after the expiration of the agreement.

The impetus for the break was a CAB recommendation that two new US airlines (Northwest and Delta) be given US-UK routes, in addition to the existing Pan Am, TWA and National. Also, the British alleged that 1976, U.S. airlines had made $513 million in revenue from US-UK flights, while British airlines had only made $228 million, which was a 69-31 split instead of the 50-50 split they had always wanted.

Negotiations on a new agreement quickly commenced under the Ford Administration, but went nowhere. In February 1977, a few months after being fired by the Illinois Central, the unemployed Boyd was sitting at home when the new Carter Administration Secretary of State called, telling Boyd that the existing US and UK negotiating teams had “grown to cordially detest each other” and asking Boyd to take over leadership of the delegation.

Boyd did so, with the personal rank of Ambassador during the talks (which were held during alternating sessions in Washington and London, not in Bermuda). The talks went right up to the wire, with President Carter and Prime Minister Callaghan exchanging cables as late as June 16 and 17 as to the fine points of the agreement (and with negotiators working in London until 5 a.m. on the last night of talks, which was midnight D.C. time), but a final deal was reached in time to put a 30-day extension of the initial Bermuda agreement into place by June 21, which then allowed the “Bermuda II” agreement (text here) to be signed (in Bermuda) by July 23.

The best summary of the negotiations and the agreement is in the voluminous statement Boyd submitted at the Congressional hearing on the agreement in September 1977. The agreement was not a complete win for the US (how could it be, given two equal and sovereign negotiating partners, one of which was so upset by the old deal that they canceled it), and it was a far cry from the “open skies” principles that the US had consistently sought since World War II, but it preserved the peace until the British government could privatize British Airways in 1987, at which point several additional and liberalizing changes to Bermuda II started being adopted, with more cities and carriers allowed.

Bermuda II was superseded by the US-EU open skies agreement in 2007. That agreement will become void for the UK when Brexit takes effect, but the US and UK have already adopted an open skies agreement to take effect when that happens.

As he was leaving the Ambassador job, Boyd lobbied Carter to make DOT the primary government decisionmaker on international aviation agreements, which at the time was handled by a joint State-Transportation-CAB committee. A year later, Carter agreed to some of Boyd’s ideas, which had subsequently been put forth by Transportation Secretary Brock Adams.

After retiring from Airbus in 1992, at age 71, Alan Boyd spent a pleasant retirement in the Seattle area. He lost his beloved wife of 64 years, Flavil Townsend Boyd, in 2007. He is survived by his son, Mark, Mark’s wife Nancy, and grandchildren heather and Alan.

Secretary Boyd’s 2016 memoir, A Great Honor: My Life Shaping 20th Century Transportation is available from Amazon here and from Barnes and Noble here. The four-part oral history interview that Boyd gave for the LBJ Library in 1968-1969 is also useful:

- Part 1 – Civil Aeronautics Board, Under Secretary of Commerce, drafting and advocating for the DOT creation bill.

- Part 2 – Getting the DOT creation bill enacted, getting named Secretary, relations with LBJ, hiring staff.

- Part 3 – Organizing the new Department, using the Coast Guard, the NS SAVANNAH.

- Part 4 – Selecting a logo, working with other Cabinet agencies, highway beautification, maritime program, Robert McNamara, Richard Nixon and Lady Bird Johnson.