October 14, 2016

Fifty years ago tomorrow, on Saturday, October 15, 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the bill that created a new U.S. Department of Transportation.

The enactment of the law was the culmination of a lengthy process of policy development and legislative action, all of which is chronicled on Eno’s now-complete Documentary History of the Creation of the U.S. Department of Transportation webpage.

An internal Johnson Administration task force had recommended the creation of a DOT over a year before (in September 1965). It took six more months before the President delivered his transportation message to Congress and sent up a proposed bill creating the Department. Extensive Congressional hearings occupied April, May and June, and private committee deliberations lasted even longer. The House debated and passed its version of the bill in late August, and the Senate followed suit in late September, setting up House-Senate negotiations on a final bill.

The House and Senate versions of the bill had diverged substantially. In an October 1 memo to President Johnson, the White House’s liaison with the House of Representatives, wrote that “with the exception of the inclusion of the Maritime Administration, the House bill is infinitely better than the Senate bill. Put another way, the House bill contains 4/5ths of the original proposal in excellent shape, and the Senate bill contains 4/5ths of the original proposal in bad shape.”

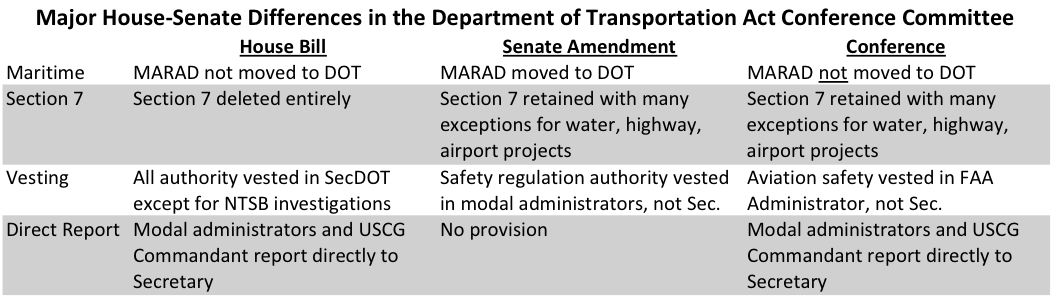

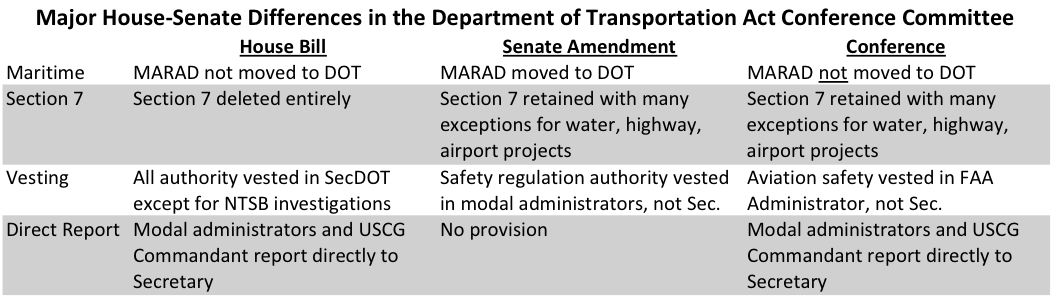

By October 5, both the House and Senate had made the formal appointments of members of a bicameral conference committee to reconcile the differing provisions of the bill (the House vehicle, H.R. 15963, was used). The House staff and Senate staff produced separate documents outlining all of the differences between the two bill versions, but there were four major areas of disagreement.

After a fierce battle from maritime interests, the House had voted, 260 to 117, to keep the Maritime Administration at the Commerce Department and not move it to DOT. Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation Alan Boyd, the favorite to be the first SecDOT, had waged war against MARAD’s operating subsidies, and Boyd thought that the opposition to moving MARAD to DOT was personal. The Senate bill moved MARAD to DOT but provided that internal MARAD subsidy decisions would be “administratively final” and could not be overruled by the Secretary.

The House also killed the infamous section 7 of the Administration proposal, which was supposed to allow the Secretary of Transportation to set government-wide cost-benefit analysis standards for all transportation projects. The Senate kept section 7 but exempted Corps of Engineers water projects and “grants-in-aid” projects (which at that time meant Highway Trust Fund projects and airport grants), rendering it largely meaningless. The Senate bill also gave Congress final approval of the standards.

And the Senate bill differed from the House version by bypassing the Secretary when it came to statutory responsibility for certain safety programs. Whereas the responsibility to carry out most transportation laws was vested in the Secretary by both bills, the Senate bill the authority to carry out safety-related provisions with the FAA, FHWA and FRA administrators for items in their purview. The Senate bill also did not include the House provision allowing the modal administrators and the Commandant of the Coast Guard to report directly to the Secretary, meaning that, in theory, the Secretary could make them report through an Assistant Secretary or the Under Secretary.

The formal agenda for the conference committee meeting suggested several potential areas of compromise, and the conferees agreed that the House would win on maritime and on direct reporting to the Secretary. The Senate won on section 7 and the conferees split the difference on vesting of safety responsibilities in modal administrators instead of the Secretary – aviation safety authority was vested in the FAA Administrator but rail and motor carrier safety were largely vested with the Secretary. The formal conference report to accompany H.R. 15963 was filed on October 12.

From there, things moved quickly. The House and Senate both debated and passed the conference report the following day, October 13 (the House debate is here and the Senate debate is here). In both instances, debate was brief and passage came by voice vote. The Senate acted first. Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-WA), who had taken over as bill manager for Government Operations chairman John McClellan (D-AR), bragged that “the conferees were able to keep the Senate version intact with one exception – the transfer of maritime functions.”

House manager Rep. Chet Holifield (D-CA) said that “In return for their concession in deleting the maritime functions, the Senate conferees demanded that we agree to leave in the bill the section on transportation investment standards in the form in which it had passed the Senate…A Senate clause which would make the decisions of the Railroad and Highway Administrators administratively final with respect to [safety] functions was limited in the conference to decisions on matters involving notice and hearings required by statute.”

The bill was signed into law less than 48 hours later. The day of the bill signing dawned with drama. That morning, The New York Times ran an exclusive article stating that “Joseph A. Califano, Jr. is expected by industry sources to be named the nation’s first Secretary of Transportation” and implying that President Johnson might make the announcement at the bill signing ceremony later that day.

The article noted that Alan Boyd had been expected to be named Secretary, but that Boyd was “understood to be considering leaving government service to become president of the Association of American Railroads.”

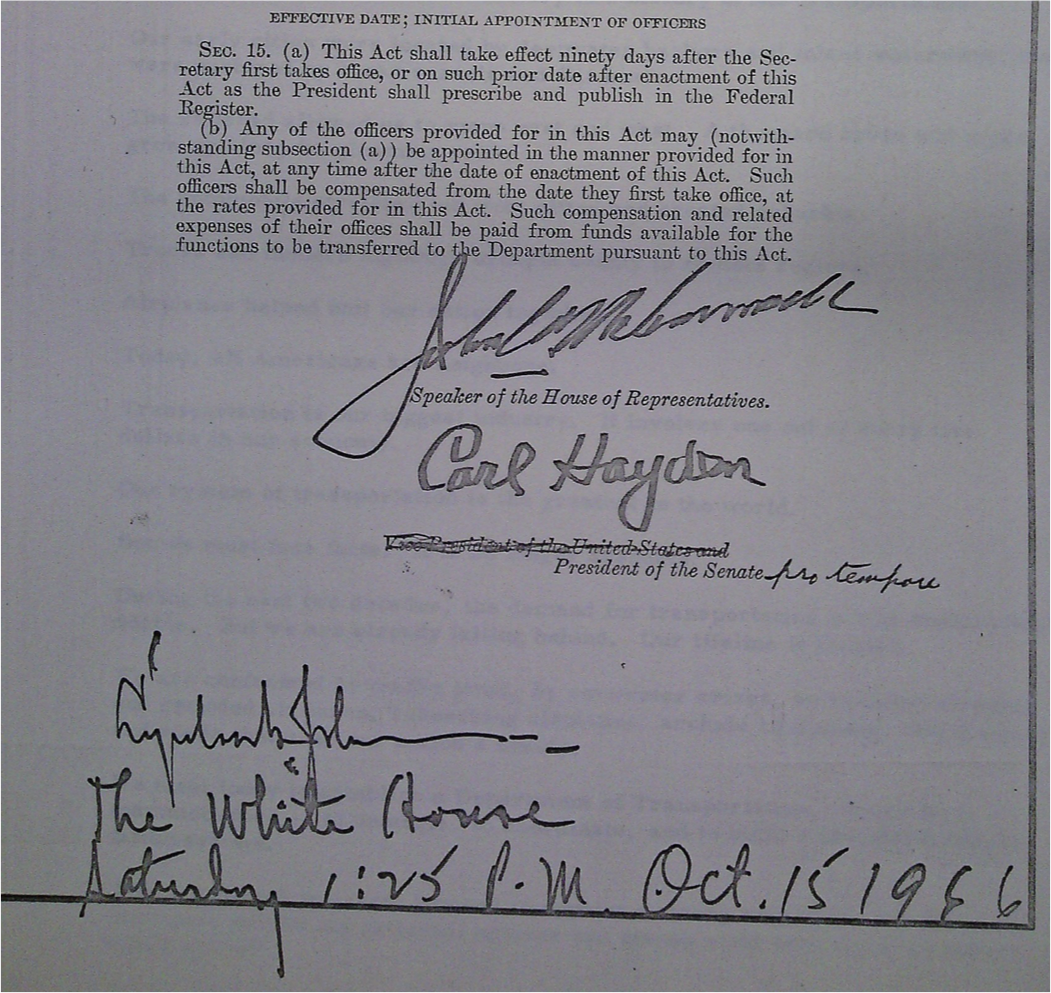

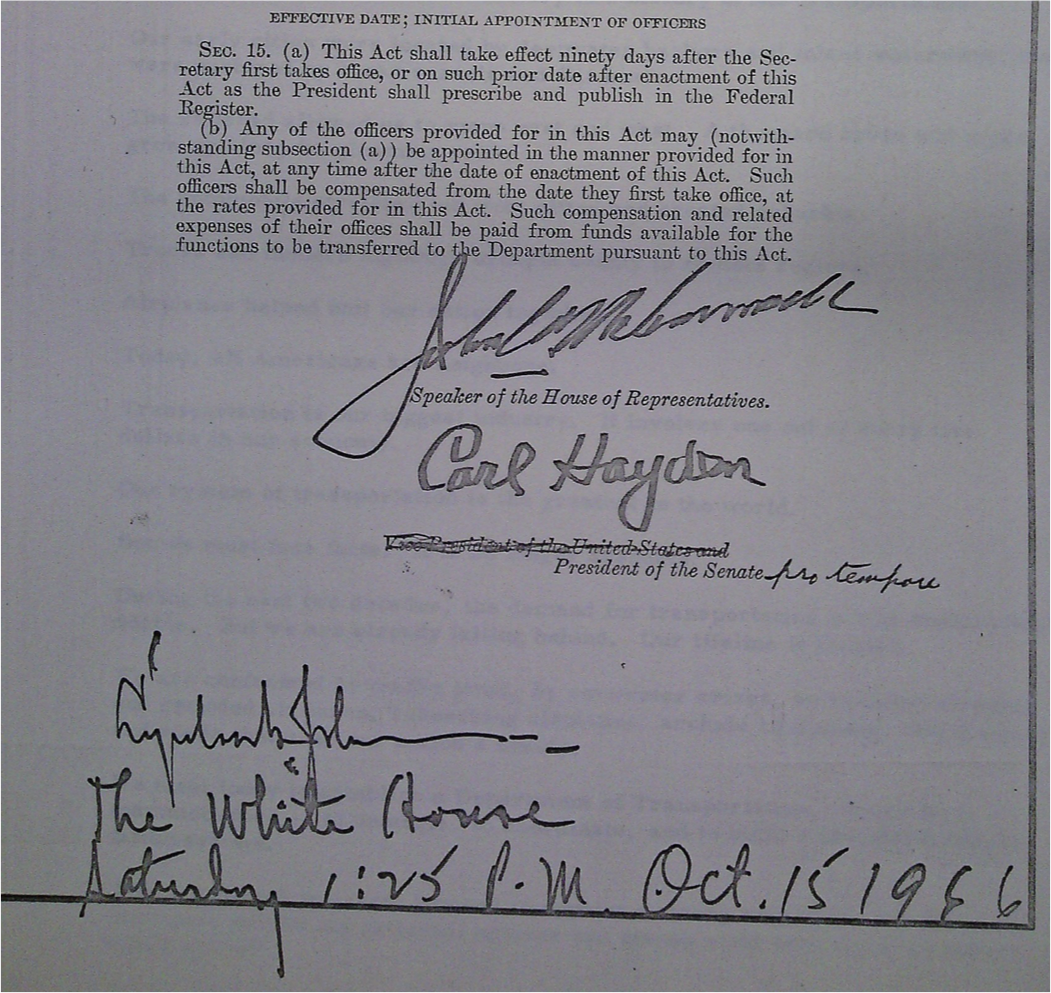

At 1:15 p.m, President Johnson left a meeting with two dozen big-city mayors to walk to the White House East Room, where a crowd of about 200 Senators, Congressmen, agency heads, transportation company, association and union leaders, and key staffers (attendance list here) watched Johnson give some short remarks and then, at 1:25 p.m., sign the bill into law.

Johnson said:

We have come to this historic East Room of the White House today to establish and to bring into being a Department of Transportation, the second Cabinet office to be added to the President’s Cabinet in recent months.

This Department of Transportation that we are establishing will have a mammoth task–to untangle, to coordinate, and to build the national transportation system for America that America is deserving of.

And because the job is great, I intend to appoint a strong man to fill it. The new Secretary will be my principal adviser and my strong right arm on all transportation matters. I hope he will be the best equipped man in this country to give leadership to the country, to the President, to the Cabinet, to the Congress.

Among the many duties the new department will have, several deserve very special notice.

- To improve the safety in every means of transportation, safety of our automobiles, our trains, our planes, and our ships.

- To bring new technology to every mode of transportation by supporting and promoting research and development.

- To solve our most pressing transportation problems.

A day will come in America when people and freight will move through this land of ours speedily, efficiently, safely, dependably, and cheaply. That will be a good day and a great day in America.

But after that buildup, Johnson confounded the Times and did not name a Secretary-designate. Instead, he gave more general remarks about the accomplishments of the bill and then closed by bragging, “And I don’t guess it would be good to say this, and I may even be criticized for saying it, but this, in effect, is another coonskin on the wall.”

Left to right: Treasury Secretary Henry Fowler, Sen. Carl Mundt (SD), Rep. Florence Dwyer (NJ), Sen. Jennings Randolph (WV), Rep. Chet Holifield (CA), Sen. Warren Magnuson (WA), Sen. Henry Jackson (WA), Commerce Secretary John Connor, and House Speaker John McCormack (MA) watch President Johnson sign the Department of Transportation Act into law.

Just after 8 p.m. that evening, Johnson finally connected with Boyd over the telephone. During that conversation (a recording of which is here – an unnamed White House aide starts the conversation with Boyd and then connects Boyd with LBJ), Johnson interrogated Boyd as to which White House staffer had told Boyd that Johnson was leaning towards appointing Califano, but Boyd refused to give up the name. Johnson said that Boyd was right at the top of his list for Secretary but he had not made a decision yet.

(Johnson dismissed AAR as “some goddamn bunch of fat cat railroad operators” and Boyd told Johnson he was not interested in the job.)

The Department of Transportation Act became Public Law 89-670. Johnson would announce on November 6 that Alan Boyd would indeed become the first Secretary of Transportation. (Joe Califano would become Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under Jimmy Carter ten years later.) The new Department would begin operations on April 1, 1967. And the Maritime Administration would eventually be transferred to DOT – in 1981, under Ronald Reagan (see Public Law 97-31).