July 6, 2016

As ETW noted earlier, last week marked the 100th anniversary of the House and Senate approving the final version of the bill that created the federal-aid highway program. The bill (H.R. 7617, 64th Congress) was then sent to President Wilson, who waited until July 11, 1916 to sign it into law (39 Stat. 355).

The 1916 law, and the way it was assembled, still holds many lessons for the way the federal-aid highway program works to this day.

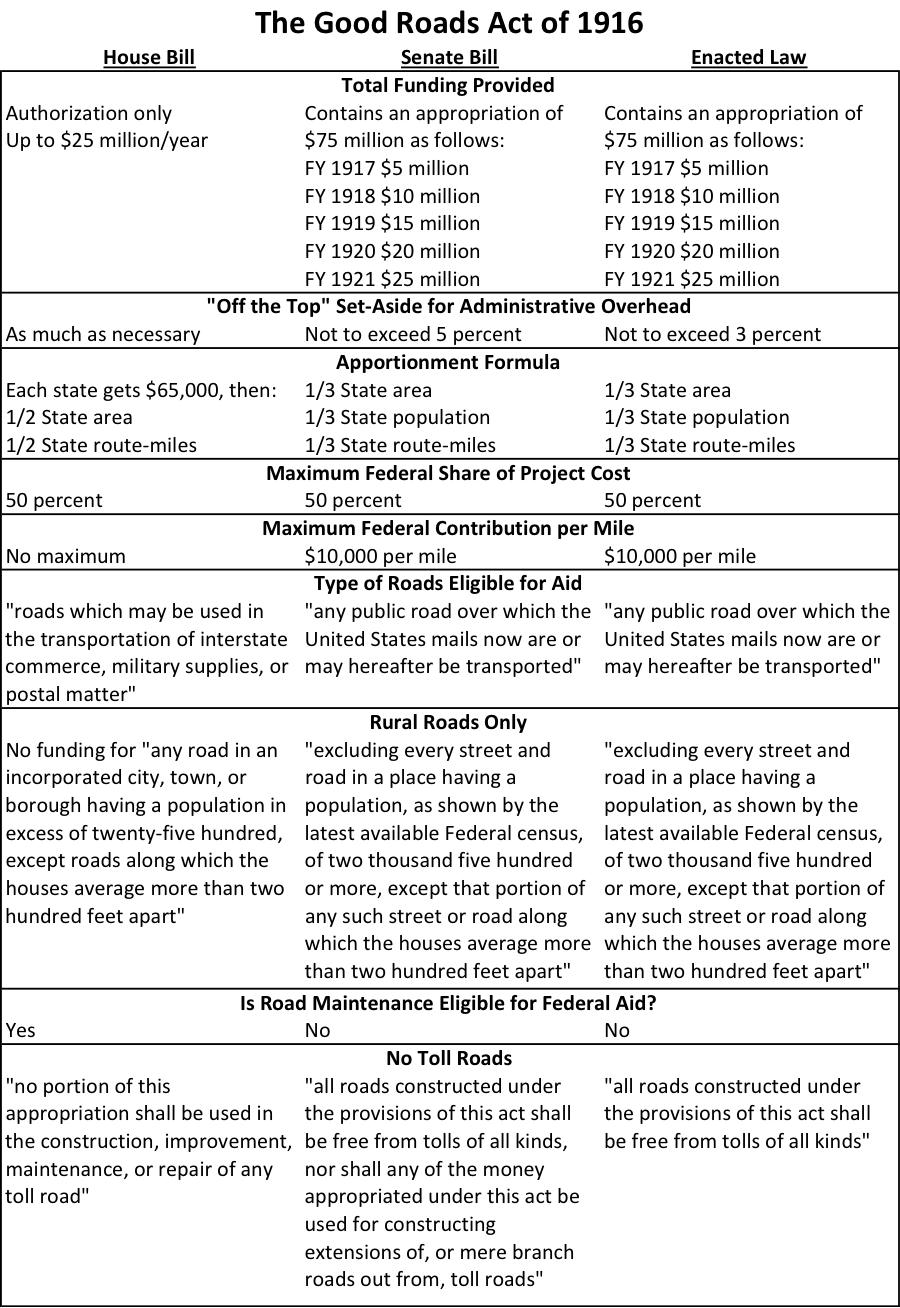

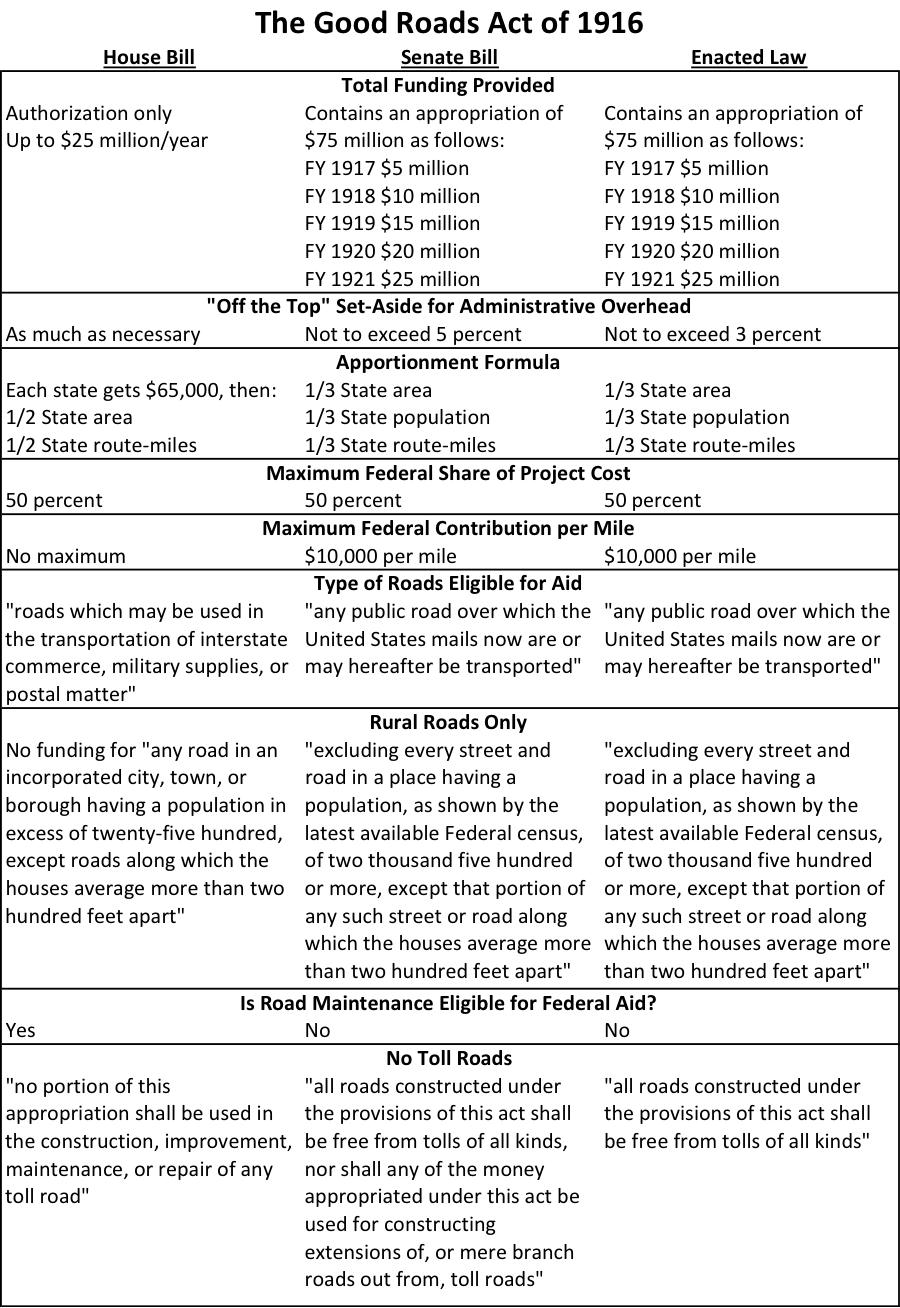

Stakeholders have always run things. The final 1916 law adhered very closely to the Senate version of the bill and not to the substantially different House version. As Federal Highway Administration historian Richard Weingroff and others have noted in the past, Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee chairman John Bankhead (D-AL) used a draft bill prepared by outside stakeholder groups as the base text for his legislation. The American Association of State Highway Officials worked with Logan Waller Page, head of the Office of Public Roads, to create a draft bill that then gained the enthusiastic endorsement of the American Automobile Association and other newly formed stakeholder groups. Weingroff notes that AASHO later estimated that it wrote about 90 percent of the enacted law.

(Four months after the enactment of the road bill, Senator Bankhead’s son William would be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (also D-AL), where he would rise to become Speaker of the House from 1935-1940.)

It’s all about the formula. The final bill used the same formula recommended by AASHO – one-third of the money apportioned by state population, one-third by state area, and one-third by the number of designated postal route-miles in each state. This formula stayed largely intact until repealed by Congress in 1991 (though separate rural and urban formulas were used starting in 1944) – for 75 years, federal highway funding was apportioned to states based on what an AASHO working group decided in Oakland, California in fall 1915.

The Senate committee report (which, for all we know, could have been written by Page and AASHO as well – it is much, much more detailed than the House committee report) contained an extremely readable justification for the formula, which is worth sharing in full:

Some plan must be adopted at the outset for determining what proportion of Federal appropriation shall go to each State. In arriving at the most feasible and equitable plan, consideration must be given to those factors which are intimately related to the public roads. First, it must be considered that primarily the road is designed for the use of people, and it would therefore seem most equitable that population should form a basic factor in determining the distribution of appropriations. A secondary purpose of the public road is the development of land so that its riches may be made accessible for the use and benefit of man, and to this end area, which would represent the great sections of country yet to be developed, should be given consideration. Along our eastern seaboard population is dense, available land is scarce, while in the in the great domain west of the Mississippi River large areas of productive land are comparatively thinly populated, but are capable of yielding rich returns under suitable development. It would seem therefore that if the interests of the East are protected by the factor of population, the interests of the West should receive consideration through including area as a factor of apportionment. Finally, the direct interest of the Federal Government, as represented by the great mileage of rural delivery and star routes for the transportation of mail and parcel post should have some weight in the granting of Federal funds, for certainly the Federal Government has a right to expect that its mail routes will be benefited by this general scheme of improvement, and so it would seem that the mileage of rural delivery and star routes should form another factor in the apportionment of appropriations.

The federal role is capital, not maintenance. The AASHO/Senate bill differed from the House bill in a key respect – the House bill would have made road maintenance costs eligible for federal aid, but the final law went with the Senate and made clear that maintenance of roads built with federal assistance was purely a state matter. The Senate report said that “…it is now generally recognized that because of lax administration and mistaken economy millions of dollars worth of well-constructed roads are disintegrating under the destructive action of heavy traffic. The Federal Government should not expend its revenues for maintenance, as by so doing it would not add to the stock of good roads, but it can make conditions which will bring about the desired results and leave the Federal revenues free for the great task of cooperating in the building of improved roads.”

This capital-only requirement gradually ebbed away in the late 1970s when states demanded federal aid for maintaining the Interstate Highway System.

A 50-50 partnership, not “insidious paternalism.” The 1916 law established the principle of a maximum federal share of 50 percent of project costs. The Senate report noted that:

While the contribution on the part of the Federal Government should be substantial, so that results of some magnitude might be accomplished, such contribution should impose on the States the duty of contributing in at least as large a measure, so that there may be no insidious paternalism established, which would stifle local initiative and self-help. If the Federal Government were to enter upon the building outright of a system of national highways, the temptation would be great on the part of States and their subdivisions to cease or curtail their own work of improvement in the hope that the Federal Government would ultimately come and make the improvements for them…An unconditional payment out of the Federal Treasury would open the door the most pernicious and dangerous “pork barrel” legislation possible to devise, as its appeal would be so universal and its demand so insistent that representatives in the Federal Congress would find it exceedingly difficult to square their sense of duty with their sense of political expediency.

After 40 years, Congress reconsidered this to some degree and made the construction of the Interstate Highway System subject to a 90 percent federal share, but the 50-50 share for the rest of the highway program stayed in law until 1973, when it began its gradual rise to the current 80 percent federal share.

No tolls. As a 2014 article in Transportation Weekly noted, the 1916 law set federal policy on tolling that continues to this day. Section 1 of the 1916 law ended with these words: “Provided, That all roads constructed under the provisions of this act shall be free from tolls of all kinds.” That provision was codified in 1958 as 23 U.S.C. §301,which currently reads: “Except as provided in section 129 of this title with respect to certain toll bridges and toll tunnels, all highways constructed under the provisions of this title shall be free from tolls of all kinds.”

The 1916 law was fine-tuned in 1921 with several key improvements. The 1921 law required states to designate up to 7 percent of their route-miles as the federal-aid network, concentrating federal resources on specific roads and ensuring that the limited dollars could do the most good. The 1921 law tweaked the formula to ensure each state a minimum apportionment of one-half of one percent of total funding each year. And the 1921 law tweaked the 50 percent federal share for states where the federal government owns a lot of land (a provision that survives to this day). But many elements of the current federal-aid highway program can be traced directly back to the original 1916 statute.